8 Volumes

Philadelphia Medicine

Several hundred essays on the history and peculiarities of Medicine in Philadelphia, where most of it started.

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Health Reform: A Century of Health Care Reform

Although Bismarck started a national health plan, American attempts to reform healthcare began with the Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressive era. Obamacare is just the latest episode.

Health Reform: Children Playing With Matches

Health Reform: Changing the Insurance Model

At 18% of GDP, health care is too big to be revised in one step. We advise collecting interest on the revenue, using modified Health Savings Accounts. After that, the obvious next steps would trigger as much reform as we could handle in a decade.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Surmounting Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

Health Insurance

Clinton Health Plan and its replacements.

July 4, 1776: Patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on Independence Day

According to the records of the Pennsylvania Hospital, the following 48 persons were patients in the hospital on July 4, 1776:

| Richard Brinkinshire (Admitted 11/15/1775) | John Ridgeway (Admitted 12/26/1775) |

| James Chartier (Admitted 1/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/6/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) |

| Mary Yell (Admitted 2/7/1776l) | John Beckworth (Admitted 2/7/1776) |

| Bart. McCarty (Admitted 2/10/1776) | John King (Admitted 2/10/1776) |

| Robert Alden (Admitted 2/17/1776) | William Patterson (Admitted 3/6/1776) |

| Elizabeth Hanna (Admitted 3/9/1776) | John McMahon (Admitted 3/13/1776) |

| Mary Burgess (Admitted 3/23/1776) | Mary Anderson (Admitted 4/10/1776) |

| John Hatfield (Admitted 4/15/1776) | Eliza Haighn (Admitted 4/17/1776) |

| Charles Whitford (Admitted 4/24/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| Susanna Carrington (Admitted 5/8/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| William Johnson (Admitted 5/13/1776) | Lazarus Chesterfield (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| Mary Spieckel (Admitted 5/22/1776l) | William Edwards (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 5/23/1776, Lunatic) | Jane White (Admitted 5/25/1776) |

| Charles McGillop (Admitted 5/29/1776) | ---Fitzgerald (Admitted 6/1/1776) |

| Michael Rowe (Admitted 6/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 6/6/1776) |

| John Hughes (Admitted 6/12/1776) | Joseph Smith (Admitted 6/15/1776) |

| Esther Munro Lunda (Admitted 6/15/1776) | Mathew Coope (Admitted 6/19/1776) |

| Anne Patterson (Admitted 6/19/1776) | Thomas Savoury (Admitted 6/20/1776) |

| Rebecca Winter (Admitted 6/26/1776) | Elizabeth Manning (Admitted 6/26/1776) |

| Negro (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Elex. Scanvay (Admitted 6/24/1776) |

| Fanny Stewart (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Peter Barber (Admitted 6/29/1776) |

| Catherine Campbell (Admitted 6/29/1776) | Ann McGlauklin (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

| Elizabeth Lindsay (Admitted 7/3/1776) | Ann Jones (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

The records indicate the following diseases were the reason for admission of those patients. Although in Colonial times there was no medical delicacy to avoid offending readers, present privacy standards require that we strip the diagnoses from the name of the patient and list them independently. There is some overlap, sometimes making it difficult to judge which disorder caused the admission.

- Sore, poisoned or ulcerated legs: 16 cases

- Lunacy, mind or head disorders: 10 cases

- Syphilis: 7 cases

- Fever and Rheumatic fever: 7 cases

- Dropsy: 5 cases

- Gunshot: 4 cases

- Diabetes: 1

- Blindness with clear pupil: 1

- Spitting blood: 1 case

- Dislocated arm: 1 case

- Inflammation of face: 1 case

- Scurvy: 1 case

- broken arm: 1 case

The following physicians were elected at the Managers Meeting dated 5/13/1776:

- Dr. Thomas Bond

- Dr. Thomas Cadwalader

- Dr. John Redman

- Dr. William Shippen

- Dr. Adam Kuhn

- Dr. John Morgan

The Cost of Meeting Unmet Medical Needs

For fifteen years before Medicare, I practiced medicine in Philadelphia. At that time, the backlog of unmet medical care seemed infinite, impossible to satisfy. For one thing, we didn't have enough hospitals to fix all the hernias, gallstone, rotten teeth, festering bad leg veins, positive blood tests for syphilis, and a dozen other matters. But we set about it, doubling the number of medical students in each school's class, and doubling the number of schools. We built or renovated and re-equipped 124 hospitals in Philadelphia alone, as I remember.

Well, we were successful. It is no longer true that everybody's teeth are rotten, or that one Wasserman test in six is positive. Instead of throwing up our hands at infinity of unmet elective surgical cases, we now hear suspicions that perhaps cataracts are being "harvested", cardiac pacemakers becoming universal apparel, tummies being tucked. But professional jealousies to one side, an undeniable statistic emerges. We only have thirty hospitals.

Backlogs are like waterfalls. The level seems limitless until it suddenly disappears from sight. We spent far too much money on new hospital capital construction, and that spending spree has to account for a major portion of the cost of medical care that now doesn't seem to be producing anything worthwhile. These are the training costs of what can now be seen as temporary construction.

These thoughts came to me when a visitor to the Federal Reserve from Kazakhstan talked recently about medical care in that vast wasteland. At a time when petroleum supplies are short, Kazakhstan has discovered it has possession of the largest new oil field in the world. The social scene is like Texas in the Twenties, or perhaps the Yukon fifty years earlier. Whereas today it is questionable whether to spend the money to perform a Wasserman in America, positive tests are widely abundant in Kazakhstan. I daresay the hernias, varicose veins, bad teeth, and whatnot are just as bad there as they were in America in 1960. And they are gunning up their engines to build lots of the biggest most expensive hospitals anywhere because they can afford them.

Prediction: in 2050 nobody will be able to explain why medical costs are so high in Kazakhstan. After all, at that time there will be no positive Wasserman, no hernias, no gallstones.

Replacing Employer-Based Health Insurance

Employer-group health insurance will surely decline because so many are dissatisfied with it.

|

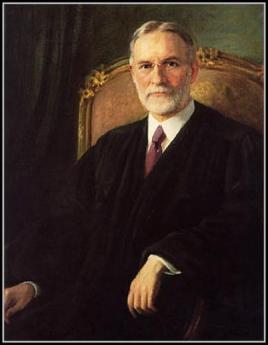

| Dr. Fisher |

Preamble

It might take a hundred pages to describe America's dissatisfactions with its health insurance system, but we mean to limit the grousing to features which could usefully be changed. The present system served us well enough for sixty years, and we tip our hat to those who struggled during depressions and war years to cobble together some kind of health financing system, never claiming it would be perfect. For reasons that were sufficient at the time, we ended up with a dominant system which is employer-based and reflects that fact. In this book we skip the quaint history, going right to the advantages of gradually migrating to better systems, which surely means migrating away from employer group purchasing. An important word is gradual because we must fix this engine without turning the motor off.

Later on, we'll return to what's significantly awkward about employer group policies, but here let's summarize complaints in a paragraph. The predicament of employers, first, is that instead of pre-paying for health care which defines what it covers and how much the items will cost, employers now pay for "service benefits". That's merely a best-efforts description of the scope, while the associated prices no longer relate to either costs or the marketplace -- undefined scope and prices are blank-check health insurance indeed. Next, many employees feel they receive a poisoned pill. They get "job lock", where insurability is suddenly in doubt whenever they change employers. Even more, employees fear what might happen to their health care if the employer must suddenly reduce expenses. Third, being outside this system is no escape from it. Congressional tax preferences seem entirely unfair to anyone who doesn't get them. In fact, even those who do get tax breaks suspect hospital cost shifting merely taxes it back. Taken as a whole, employer group benefits are a third-party system twice removed: those paying the bills suspect their insurance vendor doesn't supervise enough. But employers are reluctant to pay insurance companies more money to supervise services because they know neither one of them can directly observe it. Economists mutter the insight that health benefits really aren't employer-stockholder money at all. The money belongs to employees in lieu of higher wages, so what right do employers have to constrain how it's spent? Both employers and employees view health benefits as a boomerang they can't even throw away without getting hurt. Fairness notwithstanding, the American Academy of Actuaries estimates the waste in the third-party arrangement is at least 30% more than people would pay with their own money; that's roughly what they get as a tax deduction. Finally, the uninsured don't complain about exclusion as bitterly as you might suppose; roughly half of them could afford to buy it. The country struggles to give health insurance to absolutely everyone, but a growing number of people absolutely don't want it. There's more to say, but this should get us started.

This book asks the reader to trace complaints back to causes, and unite around objectives. The employer-based system stands in the road of other approaches, some of them quite attractive. We could rather easily work for a system where each person selects and owns an individual policy. Right now, workers participate in a group policy owned and selected by an employer. As a matter of fairness, employees ought to own and select their own health insurance, and it wouldn't be terribly hard to do. Even if you regard fairness as a loser's argument, the switch might be made so that much better products --currently blocked -- can flourish. The main focus of this early chapter is on some potential opportunities within individual ownership of health insurance, gained by employers surrendering ownership of group policies, one by one, on request by each employee. The first of the advantageous opportunities, the Health Savings Account, already exists after a long struggle. Other alternatives which follow might be even better, but experience with this one teaches some important lessons. Primarily, almost all variants require legislation, because the existing system has resorted to the government to enforce its bargains. Furthermore, sufficient public enthusiasm must emerge to persuade insurance executives that enough market exists to justify the development effort. Both Congress and the Insurance industry must be persuaded the public is behind them, and both are tough to convince. By far the best way to convince anyone of anything is to conduct demonstration projects, experiments if you will, capturing what works and discarding what doesn't.

Health Savings Accounts

Health Savings Accounts started in 1980 and by 2007 have slowly grown to ensure 13 million persons. Because of impediments in various state laws, the distribution of HSAs is uneven geographically (see Figure 1). Since the pattern closely resembles the red and blue maps of the 2004 presidential election results, observers have perhaps unfairly attributed HSA resistance to devious politics. That may be true in part, but the pattern more likely follows the distribution of laws intended to foster employer group insurance, and thus reflects concentrated industries, especially the steel, coal, and auto businesses. HSAs, therefore, tend to be legally hampered in areas of heavy union influence, although seemingly they should not injure unions or provoke their opposition, and unions may not be mainly at fault.

These HSA accounts have two components, the catastrophic health insurance policy, and the tax-sheltered savings fund. These two structures revolve around the familiar advantages of high-deductible insurance, which is considerably cheaper than fully inclusive insurance because it avoids the heavy processing costs of myriads of small claims which most people could afford to pay for in cash. That concentrates the coverage to high-cost claims which, although less common, present the dual catastrophe of often being unaffordable and almost always putting the beneficiary out of work. Almost everybody needs some kind of catastrophic protection, although the size of the deductible might vary among income levels. Secondly, to be attractive to young people and others without significant savings, the savings account feature was added, as a way of providing the funds to pay for small claims and deductibles, without losing the cost awareness of paying for services directly. This savings and insurance combination was made tax-exempt in an effort to enhance attractiveness in competition with the tax shelter now accorded to conventional health insurance provided by employers and covering the same range of services. The Health Savings Accounts, therefore, were a step in the direction of extending health cost tax exemption to everyone and shifting cost control decisions into the hands of the patient by awarding the savings to him. Permission to save unspent funds in the accounts from year to year created portability between jobs, and thus lifetime coverage. A final incentive, the ability, in theory, to strive for paid-up lifetime insurance, was thwarted in Congress by prohibiting the money in the accounts being spent on the premiums of the catastrophic insurance. It would be of some interest to know who in Congress promoted this prohibition, and what the reasoning was.

Proponents of this reform measure proceeded in their advocacy with the charming innocence of those who believed they had a splendid idea for the benefit of everyone. Anyone who resisted, must not understand the issue very well and needed only to have it explained in greater detail. This feeling was heightened by seeing groups oppose the HSA who would seemingly only stand to benefit from it. Since experience has shown that a third of those who enroll in HSAs have previously been uninsured, it would seem reasonable to expect the uninsured and those who work in their behalf, to support it. Sellers of individual health insurance were expected to recognize the enhanced commissions of selling lifetime portable insurance compared with the drudgery of flogging annual renewals. Insurance company risk was removed entirely except for the catastrophic coverage portion. Unions, who prize their ability to pressure health insurance companies on their members' behalf should welcome a role in advising members on the best choices for their money. Those who negotiate for higher wages and benefits would seemingly welcome the diminution of vague "service benefits" as a tool and the substitution of visible actual dollars into the accounts as a collective bargaining achievement. Union members individually would seem likely to carry their objections to managed care plans to the logical conclusion of reaping the rewards of cost containment for themselves, without impairing freedom to spend extra for luxuries if they please. One would have supposed union members would actively welcome the sort of insurance that gave them free choice of their doctor or hospital. Ultimately, you would suppose that union members would wish to lighten the burden of health costs of their employers if only to demand higher pay in return, or alternatively to preserve their jobs from the ravages of foreign competition. But alas, legislative experience has been quite different. Prohibiting the use of tax-sheltered accounts to pay health insurance premiums is an inexplicable clause inserted by opponents of the proposal. Prohibiting the use by employers of more than fifty employees was another. Limiting the number of people who could have these accounts to 750,000 was still another unaccountably restrictive Congressional feature. It is almost as though there was some strategy of inhibiting the spread of these policies, with the ultimate goal of calling for total elimination based on lack of interest. The original pioneers of this program, now twenty years older, trudge on in bafflement at resistance, but rather steadily enlisting new subscribers in the states where they are permitted by local law. One consequence would appear to be a resurgence of local state resistance to the interstate sale of health insurance.

In a certain way, other obstacles in the road of HSA accounts do contain some understandable logic. For the most part, they are the residuals of old state laws which once enhanced other projects with at least comprehensible goals. For example, mandatory benefits. Chiropractors, optometrists, physiotherapists and a host of other limited license practitioners fought long, hard, and expensively to lobby laws into existence mandating payment for their services as a condition for any health insurance in their state. These primarily outpatient groups see high deductible insurance as a way of raising the insurance threshold above the typical price of their services, thus excluding them from a federally subsidized system. Before ERISA was passed in 1973, special mandates were added in state legislatures by the hundreds each year. That led to interstate businesses going to Congress for relief from the need to satisfy varying requirements in fifty states. This difficulty was garrisoned by the McCarran Ferguson Act of 1945, which uniquely excludes the business of insurance from federal regulation. Just how we got here from the original antitrust dispute is hard to explain, but nevertheless, anyone can see that toppling this complicated structure would require a fierce political campaign. Therefore, by far the easiest pathway is to amend federal law to make it clear that conflicting state laws are pre-empted. Essentially, that is what ERISA accomplished, and when amendments are proposed, why employers regard ERISA as so untouchable.

Ratio of Prices to Underlying Audited Costs

Beginning this book with a discussion of the struggles of the Health Savings Account brings us to bang against what the reader will soon learn I consider the most intractable issue in American health care reform. It's an outward symptom of the issue which must be addressed if significant progress is to be made in health reform of any sort, and it won't be easy to address it. My plan is to defer analysis in depth until later, after first describing one by one how it blocks progress in every single promising proposal. Only when it seems likely the reader has become thoroughly fed up with it, will we attempt to lead through its very complicated analysis. Please be patient with a very brief introduction, first showing how destructive it is to Health Savings Accounts.

To be eligible for Medicare payment, every hospital must submit an audited Medicare Cost Report. That makes it public information, subject to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) of 1966, although rightly any competitive organization is uncomfortable about divulging business information. A significant item on the Medicare report is The Ratio of Posted Charges to Costs. That is, the audited costs are divided into posted charges of the same year. If a not-for-profit hospital just breaks even for the year, the ratio might be expected to be about 1.0. With the allowance of say 4% for bad debts, the ratio could be 1.04. Because Medicaid commonly underpays for its share, the ratio might have to be 1.20. But that reasoning gets you to the wrong conclusion; the ratio is commonly five or eight times greater than that. To make this idea more comprehensible, an electrocardiogram with costs of $25 carries a posted price of $380 in at least one hospital; that would create a Charge-to-Cost ratio of 15.02. Fifteen times its independently audited cost? There is considerable reluctance to defend or discuss this matter, so it, unfortunately, invites speculation, both fair and unfair.

The reason for introducing the charge to cost ratio at this point is to identify a vexing issue which makes health insurance seem so essential, while simultaneously interfering with making affordable insurance available. A person even a wealthy one must have health insurance to protect himself against overcharging. Those who cannot easily afford health insurance look to high-deductible Health Savings Accounts because that makes insurance cheaper. Unfortunately, cash savings within the accounts can be quickly eaten up by even moderate exposure to huge price mark-ups. The attractiveness of these accounts is thus limited to those young healthy people who have no real health expenses, and to residents of those regions of the country where the practice of massive overcharging is uncommon. Without encumbering this narrative with too much detail, that is the explanation for the slow steady progress of HSAs and their peculiar geographical distribution. If a representative charge for an electrocardiogram is $40, HSAs are a bargain. But if an electrocardiogram costs $380, purchase of HSAs is mainly restricted to those who have no great need for electrocardiograms. The outlook for HSAs is not completely bleak, however. At some time and in some areas the mass of subscribers will grow to a size where they can force the hospitals to confer a discount. Using collective purchasing power and the threat of publicity or even lawsuit, certain local brokers of HSAs have worked out arrangements for their members to receive market prices for their outpatient services. The most effective argument with hospitals has been that HSA holders do not create bad debts in their co-insurance. Unpaid deductibles and copayments are now the largest sources of bad debts for most hospitals.

While focused on the hospital markup issue, let's engage in some unproven conjecture about it. Hospitals actually construct these inflated prices, but at first glance, they would seem to have no great motive to antagonize cash paying clients this way, or to injure poor people, or to drive outpatient work toward free-standing clinics and doctor's offices. As a matter of fact, there is a small incentive in the rare wealthy foreigner who pays full freight, and the Medicare inpatient loophole of charge reimbursement for "outliers", cases with unusual costs. However, regulators are struggling to close such loopholes and cash payments are rare. I remember one oriental dignitary, reputed to own 8% of his country's Gross Domestic Product, who pulled out a wad of hundred dollar bills to pay a hospital but totally befuddled the hospital clerk who didn't know what to do with real money. For every instance of this sort of thing, there are a hundred instances of hospital administrators genuinely distressed by their own mandate to collect seriously inflated bills from poor people.

Well, if hospital top management is conflicted by devising this practice, and mid-level employees are distressed to implement it, well, who else has a motive to continue this markup? The obvious suspects are two: health insurance companies and Medicaid agencies. Obviously, sellers of health insurance rejoice in a situation where even people without important need for health cost protection must nevertheless buy it to protect against gouging. Think of an insurance executive before his home television, watching Presidents of the United States searching for ways to make their product mandatory for every citizen, and weeping because it is unattainable. Yes, health insurance companies have incentive to favor high hospital posted prices, but still it is difficult to see why hospitals would cooperate. State Medicaid agencies might also develop a motive to increase their own Federal reimbursement, and have occasionally engaged in some questionable maneuvers to do so through the arcane formulas of federal-state cost sharing. What's more, state governments are often in a position to help hospitals who play nice. In a naughty world, some of that may go on, but massive conspiracy seems implausible. So, if those with potential incentives are unable to force compliance, why do hospitals do this? Why would they persist in something they privately deplore, silently biting their lips at the criticism it provokes?

Perfect, the Enemy of Good

One problem with health insurance reform debate is there's so little mention of health. After all, without illness, the need for health insurance would vanish. So here, let's begin with the so-called statin drugs, the first really effective treatment for high blood cholesterol. Statin drugs do far more good than merely lowering cholesterol levels. Heart attacks, the commonest cause of death, declined so rapidly in the past ten years it's hard to say how low mortality rates will eventually go. Deaths from strokes, also caused by hardened arteries, declined almost as much and that's the whole purpose of treating cholesterol. Statins didn't do it all; it is about half due to prevention, where smoking cessation, aspirin, and other drugs are effective, and a half due to rescue treatments, like angioplasty, pacemakers and by-pass operations. But that's why the conquest of arteriosclerosis seems so assured; it doesn't all depend on a single drug which might later have unexpected disadvantages. Eventually, we can reasonably hope for prevention to displace rescue treatment, so maintaining the conquest of this disease should also get cheaper. This is already the most dramatic medical advance since the invention of antibiotics. No sooner do we say the mortality rate from heart attacks is down by 30% than we sense it may be down by 50%. Since it takes several decades to accumulate that rust in your arteries, the death rate from heart attacks may decline for thirty years, as we prevent rust accumulation from beginning in high school. Safety is still a question, but a small one. Right now, elated doctors whisper that perhaps arteriosclerosis has been conquered, don't say it too loud because that's bad luck.

Health insurance to cover absolutely everyone is an attractive goal but may be an unachievable digression from achievable reforms.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

Sixty years ago medical doctrine was, only two research challenges remain: arteriosclerosis and cancer. That's a little exaggerated, since HIV, schizophrenia, Alzheimers Disease, and nuclear explosions would bother us badly even after cancer is cured. But it's certainly high time to redirect the healthcare reform debates to include the massive economic changes going on, independent of any insurance reform. Let's repeat, for emphasis, we don't need universal health insurance if people don't get sick. Or put the same idea in more measured tones: Americans will almost certainly become more resistant to taxation for health insurance as this longevity extension sinks in. It may not matter that Canada, Britain, France, and Zanzibar have universal health insurance plans. Americans younger than 35 are already past the political point where the need for health insurance is self-evident to them. The conquest of arteriosclerosis could easily push that resistance level to age 50 because people form their opinions from what they see happening to friends and relatives. Employers wrap their opinion around what they see happening to their employees.

If, then, it can be feared that employers might eventually rebel at sustaining major health insurance costs for employees whose lack of fatal disease is obvious from their personnel records, the present system of employer-based health insurance coverage could crumble. At the very least, it will draw employers to proposals for individual health insurance individually selected and owned, portable between jobs. At that point, another group will rise in rebellion. The employees themselves will resolutely oppose mandatory spending for health insurance they think they don't need. Insurance against the cost of obstetrics and baby shots, yes. After retirement, Medicare will take care of the ills of old age. Costs will progressively concentrate around the first year of life and the last year of life -- ninety years apart. Everything in the middle will depend on how much risk people are willing to take, and that depends in turn on how much the insurance costs. The fate of the whole health insurance industry depends on reducing claims costs, but their track record on that is quite poor. Consequently, their future attempts will likely be quite drastic, making insurance even more unpopular. For all these reasons, it is going to be very difficult to persuade the country to accept any reform that includes the word "mandatory". People may be restless with present forms of health insurance, but it's hard to imagine them switching to an alternative from which there is no retreat.

There's a great deal more to say, but let's veer to new unwelcome consideration. For sixty years, since the administration of President Harry S. Truman, we have embroiled ourselves in a struggle to achieve health insurance for everybody. Many quite practical solutions to smaller problems have meanwhile been swept aside, as either irrelevant to the Main Thing, or hindrances which reduce the urgency of it. Somehow it has always seemed worth concentrating on the big reform of universal coverage while smaller conflicting improvements are forced to wait for the dust to settle. But the problem of 12 million or more illegal immigrant workers begins to demand solutions which have nothing to do with health insurance and may make universal coverage impractical for decades to come. Illegal immigrants appearing in the accident rooms of border states were a manageable problem until their numbers grew so substantially. Since we obviously cannot extend free coverage to the whole undeveloped world, no proposal for universal health insurance is viable without a workable feature about non-citizens. Mix in the local politics of the border states and it is entirely possible that the exigencies of overall immigration will prove greater than the need to have a uniform health insurance system. The longer it takes to face this unpleasant reality, the longer we will delay small, non-universal, solutions to health care reform.

Although it is a digression from healthcare, it seems important to make a convincing case that immigration is a serious issue. The terrifying fact is, we have grown to need immigrant labor. The experience we gained in centuries of dealing with new waves of immigrants is not much help in coping with the new phenomenon of transient laborers in massive numbers. Historically, we struggled with bilingual education and crime ghettos and mostly learned how to deal with that. Now, we need to fear the example of the rich Arab countries where transient foreigners greatly outnumber the citizens. The most extreme result is found in Kuwait, where hardly a single Kuwaiti citizen in gainfully employed; the rich citizens are helpless parasites on the labor of the illegals. Try proposing universal health care in Kuwait and see how much attention it gets. At the risk of being called an insensitive person, I'm afraid that being the richest country in the world may be exactly the reason why we can't do what Europe has done with health care. Meanwhile, this distraction keeps us from doing what we really might be doing.

* * *

In its thirty-year existence, cable television's C-span diligently filmed mountainous archives of mostly boring speeches, hearings and contemporary analyses of our government at work. The true genius of this expensive private philanthropy emerges with hindsight, as old firms which hardly anyone watched at the time can sometimes re-emerge to display what now everyone needs to know. The present case in point is to listen again to the soaring, convincing rhetoric of Bill Clinton's introduction of his Health Plan to Congress in 1993, bringing America to its feet with a realization that something was terribly broken about American health care. And then to be present in the next hour to the fumbling, circular and unconvincing solutions offered by Hillary Clinton before the sly, elaborately courteous, but pointedly probing questions of the Congress in hearings. She improved considerably with practice, but it is not lost on the viewer that she reverted to emphasizing the seriousness of the problem, rather than the aptness of the solution. The Plan was going to spend some money at first, save a lot of money later, but not harm the quality of care in the process. Just how it was going to do that was mainly supported by a passionate wish to do it because it simply must be done. Total, universal, and hence mandatory, insurance coverage would, must, shall cut costs while it extended decent care to all. All other solutions had been exhaustively examined. Without total universal mandatory insurance coverage, nothing would work.

However, if one problem would make this solution unworkable, it is not necessary to describe twenty others. There are billions of people around the world who do not have American health insurance; obviously, we do not expect to extend it to all of them. It would seem that we are talking about extending, giving, or mandating American health insurance to those who are within our borders. Assuming we ignore the handful of foreign tourists who pass through, that mainly means extending coverage to immigrants and those without coverage for brief periods, mainly new employment entrants and those temporarily between jobs. Switching from employer group policies to individually owned and selected policies would solve half the problem, but at the cost of extending income tax deductibility to everyone, hence eventually eliminating it for everyone. It would take a lot of persuading to convince everyone to give up that tax deduction, particularly when it is scarcely mentioned in the persuasion. But then let's look at the other half of the problem; we have 12 or more million illegal immigrants in the country, is someone proposing we mandate health insurance for them? What about next year, when several million immigrants go back home and are replaced by several million different ones? When you dig into it, this sounds less and less like a health insurance problem, and more like an immigration problem. Would it not seem wise to delay the goal of universal coverage and solve other health problems while other people with other ideas solve the immigration issue?

And then, the issue of raising taxes by eliminating the tax deduction for health insurance. A considerable portion of this revenue source would be absorbed by subsidizing the people who don't currently get the deduction, which not only includes the uninsured but those who currently pay for their own health insurance, mainly the self-employed population. The residual federal revenue gain from the net effect of all this disruption would probably fall short of its promises, but even if it produced mountains of federal revenue, would it reduce the cost of medical care? It's pretty hard to see how shifting money from one set of pockets to another would have any effect whatever on the cost of running a hospital or doctor's office or pharmacy.

Whenever the Clintons or their spokesmen fumbled a little, it was possible to believe they did not fully understand the irrelevance of their solution to the problem they denounced. And whenever the Clintons appeared glib and polished, it was possible to believe this was all some sort of ruse. They couldn't win, and others seemed to grasp this before they did. Meanwhile, potentially important progress in the improvement of medical care was totally blocked by insisting that every proposal must meet the test of universal coverage. Tort reform, increasing the share of patient cost responsibility, permitting the interstate sale of health insurance, and -- stop right there, how will that ensure the uninsured? By forcing every proposal, large and small, to be measured by whether it led necessarily to universal coverage, the debaters "framed the argument". Fifteen years later, we can see the country did get by without meeting that benchmark, and we also see how many useful improvements were pushed aside for failing to meet the standard of an impossible goal made possible.

Time To Care

|

| Dr. Norman Makous |

It sometimes seems as though Medicare has been a standard part of the scene for so long it now needs major reform, but when a doctor has practiced Medicine for sixty years he has seen a lot of contrasts between the old way and the new way, not all of them favorable to the new -- which we are now tired of, and trying to repair. That's particularly true if the doctor practiced at America's first and oldest hospital, because it sustained many traditions from two centuries before, and was among the last to yield to the imperatives of newcomers for the last forty years, their hands grasping for the purse strings. Dr. Norman Makous must either have a remarkable memory or a thick, detailed diary. He tells three hundred pages of fast-reading anecdotes about sixty years of his own medical practice, before summing up in fifty pages of reflection. One by one, he describes the innovations in his field of cardiology and how they affected him and his patients. Thiomerin, one of the first of many easy ways to pump out excess body fluid accumulation, transformed the treatment of congestive heart failure. Synthetic digitalis claimed to but probably did not much improve things over dried digitalis leaves; it certainly raised the cost. Cardiac catheterization, electro-shock resuscitation, ultra sound diagnostics, MRI and CAT scans, cardiac surgery using the heart-lung machine, and finally cardiac transplants -- all started out as headline-news spectaculars, evolved into cutting-edge advances, and then settled down into the Standard of Care that you obtained a plaintiff lawyer to sue about. All in one medical lifetime, supposedly prepared for by one Medical School course, followed by one residency apprenticeship, the specialty of Cardiology was completely transformed at least six times.

Meanwhile, the leadership of the medical profession was tenaciously resisted by those who supposedly followed its direction. Hospital administration.

Finding the Nerve to Cut Health Costs

WASHINGTON

Over the next several weeks, members of Congress will be confronted with one scary story after another about what will happen if they try to cut health care costs.

Tax the costliest health insurance plans? Workers will be denied medical care. Reduce the growth of spending on home health care agencies? Elderly patients living alone will be left to fend for themselves. Set up a commission to reduce Medicare waste? Again, the elderly will suffer. Impose a tax on plastic surgery? That’s unfair to unemployed women looking to enhance their appearance. (Seriously, the plastic surgeons are making that case.)

But here’s the thing: It is abundantly clear that our medical system wastes enormous amounts of money on health care that doesn’t make people healthier. Hospitals that practice more intensive medicine, to take one example, get no better results than more conservative hospitals, research shows. And while the insured receive better care and are healthier than the uninsured, the lavishly insured — those households with so-called Cadillac plans — are not better off than households with merely good insurance.

Yet every time Congress comes up with an idea for cutting spending, the cry goes out: Patients will suffer! You’re cutting bone, not fat!

How can this be? How can there be billions of dollars of general waste and no specific waste? There can’t, of course.

The only way to cut health care costs is to cut health care costs and, in the process, invite politically potent scare stories.

I’m as skeptical as anyone of the ability of the United States Congress to formulate good policy, but the last few days have offered a reason to hope that its members may be summoning the political courage to endure the scare stories.

That would be a big deal. Health costs, through Medicare, are the main source of the huge long-term budget deficit. In recent years, they have also caused insurance premiums to rise so quickly that employers haven’t had the money to give workers a decent raise. David Cutler, a Harvard health economist, estimates that the measures already in the health bills will increase the typical family’s income $2,500 a year by the end of the decade.

Real health reform also has the potential to save lives. Because we now pay doctors to provide more care rather than better care, we have not given them an incentive to reduce hospital-acquired infections and other avoidable errors. A new amendment from three senators — Susan Collins, a Maine Republican; Joe Lieberman, the Connecticut independent; and Arlen Specter, the Pennsylvania Republican turned Democrat — would increase the financial penalty for giving patients such infections.

Even this idea, however, has its own scare story. The Washington Post reported on Sunday that hospital groups were & quietly steaming; over it and suggested their support for health reform could be in danger.

•

One piece of encouraging news came on Saturday, when the Senate finally began listening to its own health care advisers.

To help it oversee Medicare, Congress set up an outside board of doctors, economists and other experts in 1997, called the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Medpac, as it’s known, tries to figure out which services Medicare may be paying too little for, thus creating shortages, and which ones it may be overpaying for.

Perhaps the single clearest example of an overpayment is home health care. Home health agencies, which care for Medicare patients with specific health needs (as opposed to those receiving general long-term care), have been proliferating in recent years. Yet, according to the most recent data, they still had fat profit margins on Medicare, 16.6 percent. One reason, the Government Accountability Office found, was that fraud was rife.

So MedPAC has recommended cutting home health payments, and the Senate bill would do so, by 13 percent over 10 years. On Saturday, the Senate rejected a Republican amendment, supported by a few Democrats, too, that would have blocked that cut.

The home health provision is actually typical of the cost-cutting measures that have made it into the Senate bill: it’s pretty good. It won’t be perfect, obviously. Some people somewhere may indeed have to stop working with a home health agency they like and find a new one. But that’s not a reason to waste billions of dollars a year subsidizing an industry’s profits.

The real problem with the Senate bill is that it doesn’t go far enough to cut costs and improve care. Here too, however, there are positive signs. For months, centrist Democrats have been saying that cost containment was one of their biggest priorities, but they had not done much to help the cause. That has now started to change.

“ Senators are now really focused on cost containment,” says Mr. Cutler, who has been advising some of them.

The day before the Senate defeated the home health care amendment, Senators Collins, Lieberman and Specter introduced an amendment with some measures to push medicine away from the insidious fee-for-service payment system. The cost-cutting momentum continued on Tuesday when 11 of the 13 freshman Democratic senators announced their own package of measures. Neither proposal is earth-shattering, but both would make a difference.

Among other things, the freshmen’s proposal would do more than the current Senate bill to push insurers to use a standardized payment process. Right now, doctors and hospitals often have to fill out different forms for different insurers. “There’s a lot of money there,” Len Nichols, head of health policy at the New America Foundation, says.

Intriguingly, officials from a rainbow of special interest groups showed up at the freshman senators’ news conference to praise the proposal. To me, their presence highlighted both the biggest strength and the biggest weakness of the proposal. On the one hand, it has a real chance to make it into the final bill. On the other hand, it, like the Collins-Lieberman-Specter amendment, also fails to fix the single biggest flaw in the Senate bill.

Last month, Senator Harry Reid, the Democratic leader, gutted an independent commission — a more powerful version of MedPAC, meant to shield Medicare payment decisions from political interference — that many economists consider necessary. Mr. Reid’s bill would allow the commission to take action only if Medicare spending was rising even faster than total health spending. If total spending rose 8 percent one year and Medicare spending rose 7.9 percent — a miserable situation — the commission would have to sit on its hands. AARP, unfortunately, has emerged as an opponent of a strong commission.

But without one, health reform will be hobbled. And the Senate may be the only hope for changing it.

The House has shown little interest in cost control. President Obama and his administration have pushed aggressively for it, but they have limited leverage. Mr. Obama can’t credibly threaten to veto any of the health reform bills that now seem likely to emerge from Congress.

So after the 11 freshmen announced their plan on Tuesday, I caught up with Mark Warner, the Virginia Democrat who is the group’s leader, underneath the Capitol building and asked him how he and his colleagues would deal with the inevitable scare stories still to come: How do you respond to a lobbyist who effectively accuses you of killing patients?

“I don’t know any other way than you take incremental steps,” Mr. Warner said, “and you hope you get to the tipping point where fear and misinformation don’t have an effect, because people see these things don’t do what they are accused of doing.”

That, obviously, is the long-term strategy. In coming weeks, we’ ll see how well Mr. Warner and his colleagues deal with the immediate pressure. The Grim Reaper is a tough opponent.

A Fair Plan for Fire Insurance (and Health Insurance, too?)

|

| Penn Mutual |

The Fair Plan (sixth and Chestnut, Philadelphia) is a fire insurance company with unusual features. Some day, it is to be hoped some scholar will write a book about the highly mixed motives of the people who created it, compared with the unexpected ways it did or did not fulfill original expectations, of both its creators and its enemies. The Fair Plan only issues fire insurance on houses, if other insurance companies have turned that house down as a bad risk. Such risky houses would normally draw higher premiums for fire insurance, but the Fair Plan insures these risky houses at normal rates. Therefore, it loses money, which is made up by the other regular fire insurance companies in the state in proportion to the business they do, obviously thus raising the price of fire insurance for everybody. But in this way, Pennsylvania guarantees that everybody can get fire insurance. Is this a good idea? Might this be a way to give health insurance to all those people who can't get health insurance? Let's talk about the Fair Plan.

We'll set aside discussion of whether the Fair Plan was a product of cynical politicians pandering for votes, or whether it was a noble gesture for fairness and equality for our poorer citizens. It very likely had elements of both motives in it, but that doesn't matter any more. It's a form of hidden taxation, of course, and it has the result of making Fire Insurance seem more expensive in Pennsylvania than in other places that do their social work with real taxes. Go too far with that, and people will end up buying their insurance in Bermuda instead of boarded-up former fire insurance companies in Pennsylvania.

As the story is now told, the regular insurance companies had a choice of taking the "substandard" applicants in turn ("Assigned Risk") or creating a new company (Joint Underwriting Association). They decided they preferred the JUA. So a company was formed which specializes in nothing but bad risks, including a few arsonists and other unmentionables, but mostly poor people in bad neighborhoods. If we are ever thinking about following the Fair Plan model in health insurance, it would run the risk of being accused of creating a two-class healthcare system. But no one seems to bring up that rhetoric about fire insurance, primarily because there is comparatively little intrusion of politics in the matter, This system is given orders to spread the extra cost of universal fire insurance out to the policy holders of all fire insurance, and it does it very efficiently, without extending its mandate into setting firefighter wages, running fire departments or repainting scorched woodwork. The fundamental decision was whether to spend Society's money this way. Once that decision is taken, the task is to do it efficiently. Notice, this is not compulsory fire insurance; it is compulsory availability of fire insurance.

After the Fair Plan had been running for ten or so years, a funny thing emerged. There were years when the Fair Plan made a profit! The fire insurance industry had absorbed the Fair Plan into their scheme of things, and felt free to increase the number of applicants they rejected, during years when money was tight or business was bad. If you had compulsory availability of fire insurance, the provision of a company which could not refuse an application made it possible for every other company to refuse when it pleased. When the economy encouraged rejection, a better class of applicant came to the Fair Plan, which made the plan more profitable. When economic conditions reversed, this reversed, and the Fair Plan again lost money. For this reason, the insurance industry is very anxious to prevent the Fair Plan from becoming political, or getting tangled up in worthy but extraneous ventures. And that's probably a good model, too, if we are considering adopting a similar system for the health insurance world: stick to your mission.

Since this simple, tested idea never seems to get into the discussion phase of present agonizing over health insurance for the uninsured, it's one clear sign that such discussions at present are not terribly serious.

Political Parties, Absent and Unmentionable

|

| King George III |

BECAUSE America had recently revolted to rid itself of King George III, the Constitutional framers of 1787 sought to construct a government forever free from one-man rule. Inefficiency could be accepted but central dictatorial power, never. It is unrealistic however to expect a wind-up toy to keep working forever, and our Constitution creates the same worry. After two centuries, some chinks have appeared.

|

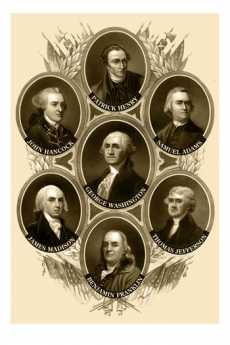

| Founding Fathers |

Political parties existed in 18th Century England and Europe, but the American founding fathers seem not to have worried about them much. Within ten years of Constitutional ratification, however, Thomas Jefferson had created a really partisan party which naturally provoked the creation of its partisan opposite. James Madison was slowly won over to the idea this was inevitable, but George Washington never budged. Although they were once firm friends, when Madison's partisan position became clear to him, Washington essentially never spoke to him again. Andrew Jackson, with the guidance of Martin van Buren, carried the partisan idea much further toward its modern characteristics, but it was the two Roosevelts who most fully tested the U.S. Supreme Court's tolerance for concentrating new powers in the Presidency, and Obama who recognized that the quickest way to strengthen the Presidency was to weaken the Legislative branch.

Dramatic episodes of this history are not central to present concerns, which focuses more on the largely unnoticed accumulations of small changes which bring us to our present position. Wars and economic crises induced several presidents, nearly as many Republicans as Democrats, to encourage migrations of power advantage which never quite returned to baseline after each crisis. Primary among these migrations was the erosion of the original assumption of perfect equality among individual members of Congress. A new member of Congress today may tell his constituents he will represent them ably, but when he arrives for work he is figuratively given an office in the basement and allowed to sit on empty packing cases. This is not accidental; the slights are intentional warnings from the true masters of power to bumptious new egotists, they will get nothing in their new environment unless they earn it. Not a bad idea? This schoolyard bullying is a very bad idea. If your elected representative is less powerful, you are less powerful.

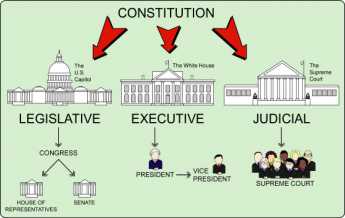

|

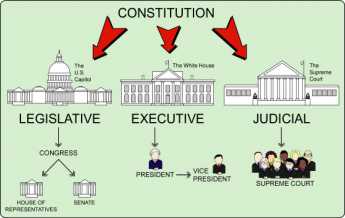

| Houses of Congress |

Partisan politics begins with vote-swapping, evolves into a system of concentrating the votes of the members into the hands of party leaders, and ultimately creates the potential for declaring betrayal if the member votes his own mind in defiance of the leader. The rules of the "body" are adopted within moments of the first opening gavel, but they took centuries to evolve and will only significantly change direction on those few occasions when newcomers overpower the old-timers, and only then if some rebel among the old timers takes the considerable trouble to help organize them. In the vast majority of cases, after adoption, the opportunity to change the rules is then effectively lost for two years. Even the Senate, with six-year staggered terms, has argued that it is a "continuing body" and need not reconsider its rules except in the face of a serious uprising on some particular point. Both houses of Congress place great weight on seniority, for the very good purpose of training unfamiliar newcomers in obscure topics, and for the very bad purpose of concentrating power in "safe" districts where party leaders are able to exercise iron control of the nominating process. Those invisible bosses back home in the district, able to control nominations in safe districts, are the real powers in Congress. They indirectly control the offices and chairmanships which accumulate seniority in Congress; anyone who desires to control Congress must control the local political bosses, few of whom ever stand for election to any office if they can avoid it. In most states, the number of safe districts is a function of controlling the gerrymandering process, which takes place every ten years after a census. Therefore, in most states, it is possible to predict the politics of the whole state for a decade, by merely knowing the outcome of the redistricting. The rules for selecting members of the redistricting committee in the state legislatures are quite arcane and almost unbelievably subtle. An inquiring newsman who tries to compile a fifty-state table of the redistricting rules would spend several months doing it, and miss the essential points in a significant number of cases. The newspapers who attempt to pry out the facts of gerrymandering are easily gulled into the misleading belief that a good district is one which is round and compact, leading to a front-page picture showing all districts to be the same physical size. In fact, a good district is one where both parties have a reasonable chance to win, depending for a change, on the quality of their nominee.

So that's how the "Will of Congress" is supposed to work, but the process recently has been far less commendable, and in fact, calls into dispute the whole idea of a balance of power between the three branches of government. We here concentrate on the Health Reform Bill ("Obamacare") and the Financial Reform Bill ("Dodd-Frank"), which send the same procedural message even though they differ widely in their central topic. At the moment, neither of these important pieces of legislation has been fully subject to judicial review, so the U.S. Supreme Court has not yet encumbered itself with stare decisis of its own creation.

|

| Three branches of government |

In both cases, bills of several thousand pages each were first written by persons who if not unknown, are largely unidentified. It is thus not yet possible to determine whether the authors were affiliated with the Executive Branch or the Legislative one; it is not even possible to be sure they were either elected or appointed to their positions. From all appearances, however, they met and organized their work fairly exclusively within the oversight of the Executive Branch. Some weighty members of the majority party in Congress must have had some involvement, but it seems a near certainty that no members of the minority party were included, and even comparatively few members of highly contested districts, the so-called "Blue Dogs" of the majority party. It seems safe to conjecture that a substantial number either represent special interest affiliates or else party faithful from safe districts with seniority. The construction of the massive legislation was conducted in such secrecy that even the sympathetic members of the press were excluded, and it would not be surprising to learn that no person alive had read the whole bill carefully before it was "sent" to Congress. It's fair to surmise that no member of Congress except a few limited members of the power elite of the majority party were allowed to read more than scattered fragments of the pending legislation in time to make meaningful changes.

The next step was probably more carefully managed. No matter who wrote it or what it said, a majority of the relevant committees of both houses of Congress had to sign their names as responsible for approving it. Because of the relatively new phenomenon of live national televising of committee procedure, the nation was treated to the sight of congressmen of both parties howling that they were only given a single day to read several thousand pages of previously secret material -- before being forced to sign approval of it by application of unmentioned pressures enabled by the rules of "the body". When party members in contested districts protested that they would be dis-elected for doing so, it does not take much imagination to surmise that they were offered various appointive offices within the bureaucracy as a consolation. As it turned out, the legislation was only passed narrowly on a straight-party vote, so there can be a considerable possibility of its likely failure if the corruptions of politics had been set aside, with members voting on the merits. Nevertheless, since this degree of political hammering did result in a straight-party vote, it leaves the minority party free to overturn the legislation when it can. The prospect of preventing an overturn in succeeding congresses seems to be premised on "fixing" flaws in the legislation through the issuance of regulations before elections can open the way to overturn of the underlying authorization. Legislative overturn, however, is very likely to encounter filibuster in the Senate, which presently requires 40 votes. Even that conventional pathway is booby-trapped in the case of the Dodd-Frank Law. The Economist magazine of London assigned a reporter to read the entire act, and relates that almost every page of it mandates that the Executive Branch ("The Secretary shall") must take rather vague instructions to write regulations five or ten times as long as the Congressional authorization, giving the specifics of the law. The prospect looms of vast numbers of regulations with the force of law but written by the executive branch, emerging long after the Supreme Court considers the central points, years after the authorizing congressmen have had a chance to read it, and well after the public has rendered final judgment with a presidential election. The underlying principle of this legislation is the hope that it will later seem too disruptive to change a law, even though most of it was never considered by the public or its representatives.

|

| Bill become a Law |

The "regulatory process" takes place entirely within the Executive branch. Congress passes what it terms "enabling" legislation, containing language to the effect that the Cabinet Secretary shall investigate as needed, decide as needed, and implement as needed, such regulations as shall be needed to carry out the "Will" of Congress. Since the regulations for two-thousand-page bills will almost certainly run to twenty thousand pages of regulations with the force of law, the enabling committee of Congress will be confronted with an impossible task of oversight, and thus will offer few objections. The Appropriations Committees of Congress, on the other hand, are charged with reviewing every government program every year and have the power to throttle what they disapprove of, by the simple mechanism of cutting off the program's funds. Members of the coveted Appropriations Committees are appointed by seniority, come from safe districts, and are attracted to the work by the associated ability to bestow plums on their home districts. By the nature of their appointment process, unworried by the folks back home but entirely beholden to the party bosses, they have the latitude to throttle anything the leadership of their party wants to throttle badly enough. The outcome of such take-no-prisoners warfare is not likely to improve the welfare of the nation, and therefore it is rare that partisan politics are allowed to go so far.

The three branches of government have become unbalanced. These bills were almost entirely written outside of the Legislative branch, and the ensuing regulations will be written in the Executive branch. The founding fathers certainly never envisioned that sweeping modification will be made in the medical industry and the financial industry, against the wishes of these industries, and in any event without convincing proof that the public is in favor. This is what is fundamentally wrong about taking such important decisions out of the hands of Congress; it threatens to put the public at odds with its government.

|

| Justice George Sutherland |

There is no need to go further than this, harsher words will only inflame the reaction further than necessary to justify a pull-back. And yet, the Supreme Court would do us mercy if it doused these flames; the Supreme Court needs a legal pretext. May we suggest that Justice George Sutherland, who sat on the court seventy years ago, may have sensed the direction of things, short of using a particular word. Justice Sutherland recognized that although it is impractical to waver from the principle that ignorance of the law is no excuse, it is entirely possible for a person of ordinary understanding to read law in its entirety and still be confused as to its intent. He thus created a legal principle that a law may be void if it is too vague to be understood. In particular, a common criminal may be even less able to make a serious analysis. Therefore, at least in criminal cases, a lawyer may well be void for vagueness. In this case, we are not speaking of criminals as defendants or civil cases of alleged damage of one party by a defendant. Here, it is the law itself which gives offense by its vagueness, and Congress which created the vagueness is the defendant. Since we have just gone to considerable length to describe the manner in which Congress is possibly the main victim, this situation may be one of the few remaining ones where a Court of Equity is needed. That is, an obvious wrong needs to be corrected, but no statute seems to cover the matter. The Supreme Court might give some thought to convening itself as a special Court of Equity, on the special point of whether this legislation is void for vagueness.

We indicated earlier that one word was missing in this bill of particulars. That would be needed, to expand the charge to void for intentional vagueness, an assessment which is unflinchingly direct. It suggests that somewhere in at least this year's contentious processes, either the Executive Branch or the officers of the congressional majority party, or both, intended to achieve the latitude of imprecision, that is, to do as it pleased. Anyone who supposes the general run of congressmen voluntarily surrendered such latitude in the Health and Finance legislation, has not been watching much television. Given the present vast quantity of annually proposed legislation, roughly 25,000 bills each session, the passage of a small amount of vague legislation might only justify voiding individual laws, whereas an undue amount of it might additionally justify a reprimand. However, engineering laws which are deliberately vague might rise to the level of impeachment.

Medicare: Restating Mathematics for a Social Goal.

It's hard to believe any problem could be too big to solve, just as it boggles the mind to think of a corporation too big to fail. But if we say the same thing often enough, we come to believe it. People who tell you Medicare is the third rail of politics, are mostly telling you they hope so.

Lyndon Johnson, Wilbur Cohen, and Bill Kissick did indeed bite off more than they could chew, but Medicare really isn't that complicated. It amounts to taking the employer-based health system floating on an enormous tax deduction and substituting three ways to pay for it. The first was to charge premiums to the old folks, which wasn't enough, only covering about a quarter of the cost. The second was to apply a 3% wage tax to younger working people, called a payroll withholding tax, which prepaid another quarter of it, by means of a gimmick called "Pay as you go". And the third, which amounted to half the cost, was supplied by taxes. The year 1965 was the time when the post-war balance of American payments turned from positive to negative, and there was something called the Vietnam War to be paid for.

So after a while, the national budget had to be borrowed, and after the manner of governments, it was borrowed by selling bonds. The largest purchaser of 10-year treasury bonds is China. So, in a general sort of way, half of Medicare is borrowed from the Chinese, and half is paid for by the clients. The debt service is temporarily bearable, but eventually, it must be confronted, and China may have to choose between absorbing the costs or going to war. Our own choice is between kicking the can further down the road, or having the confrontation right now. That is to say, right now there is time for a long-term peaceful solution, but if we delay much more, that option will disappear.

I don't plan to run for office, so let me make a proposal. Instead of continuing the pay as you go system, the withholding tax receipts should be deposited into the Health Savings Accounts of individual citizens who earned them. They should be invested into inexpensive total stock market index funds, redeemable on the employee's 65th birthday or whenever he joins Medicare. That is, redeemable by Medicare, with the residual redeemable at the death of the subscriber. The wage owner would scarcely feel the difference, but the growth of the funds would be substantial. With luck, it would pay for Medicare's deficit of 50%, putting a permanent end to Chinese borrowing, but probably not much more. It would not, for example, pay for existing debt, or retirement costs. Remember, retirement costs are legitimately regarded as a natural outgrowth of Medicare's prolongation of longevity.

The invisible costs of Medicare would eventually be paid for in two other ways: the J-shaped costs of Medicare in the last four years of life, and the contingency fund.

J-Shaped Curve All healthcare costs with the exception of premature birth, genetic disorders and the like, are migrating to older age groups. One of the main causes of disruption is the migration of costs from working people to people on Medicare. But within Medicare, costs are also migrating later in life. Half of Medicare costs are paid for the last four years of life. Since Medicare extends twenty years and growing, half of the total Medicare cost would disappear as a result of lifting this burden and placing it somewhere else. This is called the Last Four Years of Life Reinsurance, one component of the First and Last Years of Life reconstruction of healthcare finance. It will be discussed separately in later sections of this book, but a vital point is removing the cost of the last four years of life, which constitute half of Medicare cost. The consequence is to cut the remaining cost of Medicare in half, potentially funding half forward, half backward.

The Contingency Fund at Birth. And the half which is funded forward can be further reduced by investing at birth and earning investment income for eighty years. By adding the withholding tax receipts from age 25-65, the combined fund can probably pay for Medicare. Just to be certain, a contingency fund could be added at birth, amounting to around $100 at birth and growing to $25,600 at age 80, or other variations of the 256 to one ratio. We have alluded to this concept in other areas. Its power concentrates in the nature of interest rates as well as principal to concentrate at the end of debt. That is, they rise at the end, and prolonged longevity takes advantage of this fact, parallel to the tendency of healthcare costs to rise at the end of life.

For the purpose of the reader following this without a calculator, take the happenstance that money invested at 7% will double in ten years. In nine ten-year periods of extended longevity, the money will have nine doublings (90 years). Follow the bouncing ball: 2,4,8,16,32,64,128,256, 512. In ninety years, a dollar turns into 512 dollars. If the family of a newborn, or in the case of poverty the government, deposits a dollar at birth there is a 500-fold increase at death at 90. There is no sense in being more precise about all the variables in a century, and many people are more skillful than I in manipulating them. But if to this is added another doubling, the ratio becomes 1024 to one, achieved by not liquidating the fund until ten years after the death of the owner. (This feature is added as a safety-valve.)But after the most sophisticated manipulation, it is safe to predict this outcome: The revenue would exceed the need in the last four years of life, even if the seed money turned out to be a hundred times the dollar postulated in the example. There would almost surely be money left over at the end, which might be used to supplement Social Security, although we suggest funding children as preferable during the transition phase.

So that's how you could restore Medicare to some sort of solvency, plus something left over for other purposes.

What's The Matter With a Partial Answer?

It has to be noticed that developing lifetime health insurance is hampered by the considerable pregnancy and newborn costs which intrude at the beginning of the earning period from ages eighteen to forty-five. Otherwise, there is a reasonably manageable medical cost at the end of life, potentially preceded by a long period of negligible medical costs where compounded interest could be at work. So the thought naturally arises we might somehow pay for pregnancies in some novel way, essentially borrowing those costs against the future. What's involved here?

Instead of taxing each affected individual working person to subsidize his newborns and terminal care, the necessary subsidy could take place between three insurance plans, assuming the three costs to fall in separate insurances. Everyone owes a debt for being born, and everyone needs to save enough for getting old and dying. Society's benefits and costs of having children are not confined to those who have children. An unhealthy incentive to delay the first child has been created by paying for pregnancies this way, spreading the consequences to higher education and disrupted careers. Instead of regarding neonatal care as an expense of pregnancy (which we currently regard as part of the mother's health cost), just reverse matters, and include pregnancy costs as part of the baby's own debt for being born. Any move assigning pregnancy costs must somewhat fudge the transition cost of getting born without paying for it or even asking for it. Attitudes depend to some degree on whether people generally want children to help on the farm, to help care for their own old age, as entertainment or plaything, or accidentally. The theoretical fact is that pregnancy costs might be judged fairly split between the child and his parents if it were only practical to do it. Once those practicalities are addressed by covering the first and last years of life with entitlement, transfers become relatively easy. If we must have entitlements, birth and death are certainly inescapable ones.

Unfortunately, once the finance is made practical, other issues assume greater importance. Science is beginning to make single parenthood more feasible, while easy divorce makes multiple parenthood possible. Easy sharing of the costs could reasonably be resisted as a moral issue we never had, and now don't need. The longer you live, the more interest you earn on those first 26 years. But the longer you live, the more medically expensive you become, toward the other end of life. There is still a great deal of argument about what is a fair division, and much time will elapse before final resolution can be considered a settled matter. But ultimately, serious savings could occur from keeping the first and last years of life in mind as the only universal medical costs, extracting maximum savings as one argument for choosing accounting tricks to settle the pregnancy part of it. What would be left would be accidents and occasional health calamities, which paradoxically are the only parts of current health insurance which truly fit the current insurance model.

Let's give an example. Lifetime health expenses are said to be somewhere around $300,000. If you have $40,000 in a Health Savings Account on attaining the age of 65, you can passively achieve $300,000 by age 86 (which we hope is at least average life expectancy) by letting the HSA grow untouched. In this example, all other sources of health insurance revenue are available for other purposes -- they are the "profit" from using compound interest, but it is unnecessary for that to be exclusively the case. Now, the problem transforms into achieving $40,000 by age 65. That could be reached by investing $150 at birth, or $2400 at age 26. Both are achievable, neither is easy.

But it's nice to have some choice, which including the first 26 years will give you. You can even do it twice, once in the child's account, and secondly in your own. My guess is that about a third of people could spare $40,000 at age 65 right now, trading a single payment for Medicare for its present wobbly finances. With overlapping populations, 2/3 of people could afford to spare $75 from each parent of a newborn, or $150 for a single parent, in return for eliminating the obstetrical premium within their health insurance. Considering the problems of young parents, some might prefer to combine $150 with $4800 for both parents at age 26 into a financing package of $4950 spread over ten years, from 26 to 36. But notice it gets harder, the longer you wait. Finding $80,000 for both parents now aged 65 gets really hard to do, but at least the child is all paid up. If you wait, it gets pretty hard to do this without extending the retirement age to 70, sacrificing five of your thirty years of retirement, but reducing the amount you need to save by about a sixth. Nothing like these choices would be readily accepted. But the policy axiom remains: the younger you start, the easier it is to stretch the distance. And the more attractive it becomes to treat some or all obstetrical costs as the responsibility of the person getting born.

Before concluding this approach is impossible, try to remember it is quite unnecessary to make lifelong healthcare free to the last penny, although some will demand it. In fact, first-dollar coverage (i.e. making all healthcare seem free) is a big part of what got us into this mess. If we only achieve a quarter or a third of this promise, the national aggregate would amount to a stupendous amount of money. A more realistic goal might be to reduce projected medical costs by a third, offset another third with investment income, and pay a third in cash. All three of those approaches seem comfortably achievable.

As this chapter is being written, Obamacare has been struggling for three years to achieve its twin goals of reducing the cost of medical care, while improving its quality and scope. The public has long been skeptical that the two goals are incompatible. During those three years, we have achieved a cure for Hepatitis C. That cure will save millions of lives and eventually the costs will decline. In time, the public will be able to see the difference between the results of the two approaches. During that time, biological science has discovered the relationship between sleep and the circulation of spinal fluid through the brain, probably the greatest advance in physiology since Harvey discovered the circulation of blood in 1628. In another field, Joachim Frank has identified the function of the Ribosome, making strips of protein the way a zipper works, and very likely the step at the beginning of cellular life, operating at room temperature and without caustic chemicals. These three discoveries are surely less than 1% of the scientific advances of the last three years, giving promise of vast advances in the cheap production of protein drug therapies, saving of lives, and ultimately the extension of life expectancy at a lessened cost. During these past three years, what has Obamacare accomplished, at enormous cost, and widespread turmoil in the medical system?