1 Volumes

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Indigents

With a long history of welcoming and assisting the poor, Philadelphia has always risked swamping the lifeboat by attracting more of them than it can handle.

Tax Credit Time

Here's how a discouraging proportion of indigent tax credits go right into the pockets of predators.

|

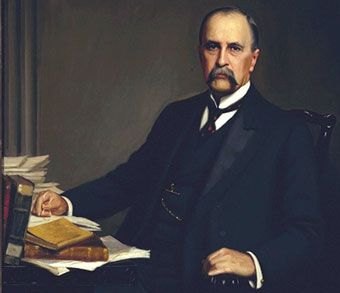

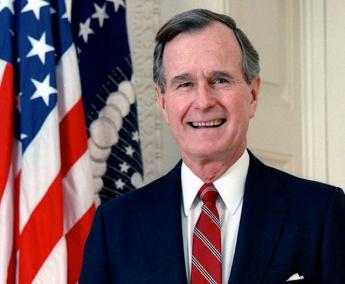

| Dr. Fisher |

If we would only listen, most people have a fascinating story to tell. They usually talk quite freely. Take an illustration from the casual observations of an employee of a tax-preparation service. For him, late February to mid-March is "Tax credit time".

Normal behavior for tax-payers is to wait until the last possible moment before the April 15 deadline, not even thinking about unwelcome income taxes. Commercial tax-preparation services have few if any tax-paying customers in March, but are nevertheless extremely busy. The chairs of their waiting area are occupied by citizens, anxious for the government to pay taxes to them as early in the year as possible.

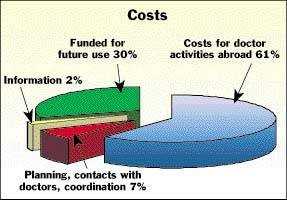

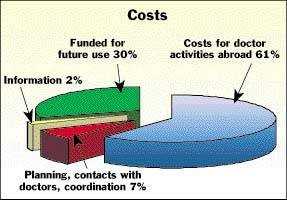

This startling role-reversal is a result of the tax credit system, which should not be confused with tax deductions. In the case of a tax credit, the government issues a check to make up the difference between what the individual earned during a year, and a certain stated income level. No doubt such benevolence is hedged with innumerable rules, restrictions, limitations, and exceptions, which tax preparation services must know all about and, in effect, certify by countersigning the completed tax form. Following that moment, there is a delay of up to three months before the green government check actually arrives. Since a loan against such pending payments is essentially risk-free, the tax preparation service is more than happy to lend it to the recipient. A fairly representative example would be to charge $200 for the preparation service, plus an additional $200 for the three-month loan of, typically, $7000 in tax credits. Where does that lump-sum payment usually go? Almost invariably, it goes to pay down the unpaid balances of credit cards, otherwise running up 18-30% interest, 23% typical. Since David Swensen of Yale's endowment fund is claimed as the world's best investor for achieving a 17% return, the welfare recipients who effectively get 23% by paying off credit cards -- are making a very good investment decision. Indeed, they aren't being swindled out of anything; they come into the tax preparation services loudly demanding just exactly this product. Although they are mainly unwed mothers in their 20s and 30s, they have obviously been well instructed by their friends about how to make quite a shrewd and entirely legal arrangement.

It's only when you ponder the further implications of this whole process that you begin to wonder if there isn't a more efficient way to handle it. Since the underlying security is the full faith and credit of the United States Government, the loan is essentially risk-free. At a time when commercial mortgages are charging about 6%, these loans imply an extra risk premium of at least 15%. If you regard the welfare client as merely a passive intermediary, a $7000 tax credit payment costs the government $1800 of it to deliver only $5200 to the client, net. That is, about a quarter of the cost of the program is going to loan sharks. Surely, a less costly method could be devised to transmit 12 monthly checks to the clients, or even 52 weekly ones.

Beyond that, there is the uncomfortable question of just where we are going with tax credits. Without begrudging a nickel to the poor unfortunates who are helped by this program, it is alarming to hear that low-income housing and historic rehabilitation of old structures are both rewarded with 20% tax credits, and the idea is spreading that it might be a good idea to pay for health insurance with tax credits. We've opened a door here that we may wish we hadn't opened. Echoing the views of Alexis de Tocqueville, Alexander Fraser Tyler has summed it up: "A democracy...can only exist until the voters discover that they can vote themselves money from the Public Treasury."

Winter of Our Discontent

|

| Lyndon Johnson |

In 1965, Lyndon Johnson diverted the (then) rapidly accumulating reserves of Social Security to support his new Medicare program for the sick elderly, along with Medicaid for the sick poor. It was a time of post-war prosperity, the country was sympathetic to the successor to the assassinated John Kennedy, and might well have agreed that the accounting trick Johnson employed was entirely justified. Unfortunately, he was making a huge financial commitment against major political opposition and felt that it was necessary to employ smoke and mirrors to accomplish a worthy goal. His lack of forthrightness however now puts his image in a bad light, when an unexpected demographic event occurred, clearly demonstrating he went beyond his mandate. The totally unforeseen event was that the unusually large generation of baby boomers collectively decided to have fewer children. The "bulge in the python" created the approaching deficit for funding retirements of baby boomers, which the boomers bitterly resent. In spite of that unusually large generation regularly making contributions of 12.4% of income toward providing for its golden years, they now approach the time to spend what they discover really isn't there. President Johnson's accounting trick, called a "unified" budget, was accomplished by describing Medicare and Medicaid as amendments to the Social Security Act. Title 18 was Medicare, Title 19 was Medicaid. Incidentally, those seeking to amend the two medical programs later have thus been destined to be confused for decades by discovering congressional oversight, lies not in the Health committees but in subcommittees of the Ways and Means and Finance Committees. The public shrugged it all off as meaningless congressional quaintness.

A major difference in the way the two medical entitlement programs are financed can if you wish to be similarly traced to quaintness in the former Kerr-Mills and King-Anderson bills, but cynics may imagine more substantial motives. Medicare is entirely a federal program, while Medicaid is nearly half financed by state taxes, while entirely administered by state governments. Federal oversight of the way its share of the money is spent was indeed provided by the enabling legislation. But states have always gone their own way in Medicaid, emitting vast clouds of offended belligerence at the least sign of federal "interference". The central unspoken issue is a recognition that if one state is significantly more generous to the poor than a nearby state, busloads of poor folks might rapidly migrate to take advantage of it. As they migrate in, employers might migrate out rather than pay higher state taxes inevitably generated by new poverty imports. State governments are happy to get the federal Medicaid money, but why must they spend it on poor people?

Whether states express this motive, they have this incentive. Either way, few exceptions are seen to a progressive diversion of federal funds for the hospital and physician costs of the poor, which is what the law intended, into something not intended, payment for nursing homes. In Pennsylvania, for example, less than 2% of the Medicaid budget is now used to reimburse physicians although reimbursement was originally quite adequate. Hospitals now uniformly complain: Medicaid reimbursements have driven away private philanthropy but pay 20% less than the cost of providing care. Indeed, the incentive to provide famous cutting-edge care is blunted for fear of attracting more Medicaid patients who would seek it. Although nursing homes are the main beneficiary of this diversion of funds, they too are funded below a level which would attract out-of-state migrants. This whirlpool of dissatisfaction has evolved during a period of wide-spread surpluses in state budgets. Total funding of the Medicaid program by the federal government is much desired by the states, but likely would not help the poor much; it would help the uninsured. What is most needed here is administrative discipline, and beyond that legislature discipline; an elusive wish since 1790.

State governors have recently taken to urging universal health insurance, but note that insurance is the only industry expressly designated (by the McCarran Ferguson Act) to have state rather than federal regulation. As a consequence, the health insurance industry is deeply intertwined in state politics. The term "Single payer system" is viewed with suspicion by the states as meaning consolidated federal administration, just as the opposite term "Socialized Medicine" alludes to supplanting professional with political control. Patients and doctors use these terms, everyone else is mainly concerned with the money. At 16% of the Gross Domestic Product, it is quite a lot. Naturally, insurance companies deplore that so many people do not own their insurance products, but it is hard to see why anyone else would feel that way.

For example, trial lawyers who even have a candidate for President, seem not to perceive a threat to their business model in total government control of healthcare; they are probably quite wrong. No one in the big industry appears to realize that health costs are progressively narrowing down to the first year of life and the last year; employers have been trapped by a tax abatement into paying for something which in time will scarcely affect their employees. When they do realize it they will surely try to escape their present posture of paying for the whole system with intergenerational transfers. Union leaders do not seem concerned that the coming bankruptcy of Ford and General Motors will probably be blamed on their notoriously generous health insurance benefits. Democratic politicians who were scarcely born when Lyndon fleeced the boomers do not seem to be concerned that the sixties generation loves to make a fuss. Although everyone acknowledges that total coverage leads to higher costs, and higher costs lead to rationing, few people seem to act on this knowledge. Residents of Blue states have scarcely heard of Health Savings Accounts, and if Pete Stark, the current chair of the Health Subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee, has his way they never will. But thirteen million people in states colored red on the political map have enrolled in HSAs, in spite of numerous obstacles which Blue politicians placed in their way. No one who wants to pay for drug costs with medical research funds seems to notice that life expectancy in America has increased by nearly twenty years in the same half-century that Russian life expectancy has shortened. Doesn't anyone want a cure for cancer or Alzheimer's Disease?

Have a nice time, suckers.

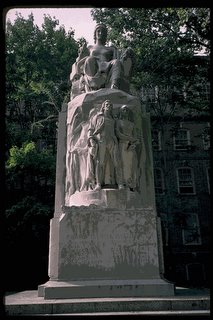

Old Blockley (P.G.H.)

|

| Old Blockley |

For a long time, the Philadelphia General Hospital was the largest hospital in town, even growing briefly to seven thousand patients during the Civil War, but leveling off at about three thousand at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. At the end of World War II, it had shrunk to about 1500 beds, but it was Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 which finally did it in. By 1977 it was costing the City of Philadelphia about five million dollars a year beyond its revenues to run the place with only 300 patients, while the running expenses of the local private hospitals were actually less, per patient. Titles XVIII(Medicare) and XVIV(Medicaid) of the Social Security act constituted Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, and in effect they made every patient at PGH resemble a walking government check in the mind of hospital administrators. The local hospital association made the argument to the Mayor Rizzo that everybody would be better off if the hospital closed and those government checks were directed to the local voluntary institutions. After a few years, the federal government inevitably squeezed the generosity out of the bargain they would of course now like to abandon. But that's the way it goes. PGH is gone and it isn't coming back. The eighteen acres in Blockley Township, now West Philadelphia, were given to the University of Pennsylvania next door, and gigantic amounts of federal money were contributed to the building of skyscrapers replacements for the original PGH. Ironically, the two hundred children's beds now on the location are fewer in numbers than the three hundred adults once considered too uneconomically few to maintain, and the cost per day of hospitalization is roughly ten times the PGH cost which had been described as unsupportable. The rest of the real estate is built up with buildings involved in medical research, which is also an activity dedicated to working for its own extinction. Discovering a cheap cure for cancer would quickly create a need to fill the vacancies with something else. No one regrets this system of creative destruction, but everyone should regret the diminution of the spirit of local philanthropy which underlay it.

PGH was one of a dozen or so big-city charity hospitals, like Bellevue in New York, Charity in New Orleans, or Cook County Hospital in Chicago. Of these hospitals, PGH had surely been the best, and at the turn of the Twentieth Century a Mayor's commission issued a report about the place which began, "Philadelphia can surely be proud...." Having worked in Bellevue and having visited most of the rest, I can testify that was likely true. When PGH was finally torn down, the walls and floors had such substantial construction that changing the wiring and plumbing to some other purpose had become almost impossible. The PGH nurses were famous for running. Although the alcoholic and drug-addicted patients might be called the dregs of society, the alacrity of the student nurses in running them bedpans or answering other calls, was spectacular to watch. When a doctor came on the floor, they jumped to their feet and were usually ready with the patient's charts, unmasked. Unlike Bellevue, where the floors were creaky and wooden, the open wards at PGH were spacious, clean, well maintained and equipped. At Bellevue, the forty-bed wards were crowded with sixty or seventy patients, so close together you could almost roll from one end of the room to the other without touching the floor. I can remember seeing one seventeen-year-old Bellevue student nurse tending such award at night alone, the intern sharpening needles, and the medical resident developing electrocardiograms in the darkroom. None of this would have seemed acceptable at PGH.

|

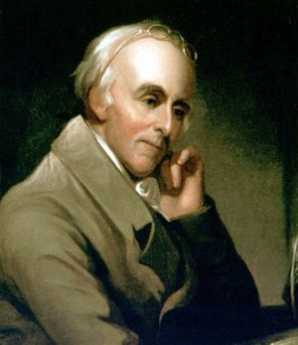

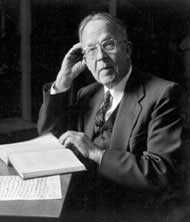

| Dr. William Osler |

Old Blockley was the place where modern systems of medical education originated. Up until William Osler came to Philadelphia, medical education mostly consisted of attending eight hours of lectures a day. Osler had an electrifying personality and wandered among the sick at PGH with a train of students following him. He is much quoted, and once suggested his obituary ought to read, "Here lies the man who took the students into the wards." A somewhat more elegant statement of the value of the practical experience was included in his dedication speech at the Boston Library: "To treat patients without books is to sail an uncharted sea. To read books without seeing patients is never to go to sea at all. Osler was somewhat underappreciated during his time in Philadelphia and went on to found the medical school at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Nevertheless, the main reason he later left John Hopkins and went to Oxford was his dismay at the adoption of the "full-time" system, which is to say the faculty stopped having a private practice of their own to act as a gold standard for their research and teaching. When all is said and done, there are some areas of discomfort in the transition of students from observers to actors. The PGH system of learning surgery was commonly reduced to a slogan, "See one, do one, teach one,"; things have progressed to the point where it is probably right for the public to insist on greater supervision and control than the old almshouse provided.

The disappearance of old Blockley ended a controversy, or even something of a mystery, about which was the oldest hospital in America, PGH or the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce. There had been an infirmary in Old almshouse at Eleventh Street, and there is no doubt the almshouse was there first. PGH grew out of the almshouse. However, there were many comments at the time of the founding of the Pennsylvania Hospital that it was now the first; that's a strange thing to say when the almshouse was three blocks away. Social historians need to look into the mindset of colonial America, which seems to have included the distinction between the worthy poor and the unworthy poor. Somehow, the founding principal of the Pennsylvania Hospital was to get people back to work who were capable of productive work, possibly even paying for itself in that way. In their minds, apparently just giving solace and help to those who were down and out was not quite the same thing.

Loaves and Fishes

|

| Philadelphia Food Bank |

Philadelphia is full of people and institutions that have done wonderful things without a lot of fanfare and hype, butPhilabundance and its executive director, Bill Clark, surely set some sort of record. The organization has been in existence for twenty years and is generally known as a nice charity that gives surplus food to poor people. And how.

With a four-million dollar budget, they distribute food at a cost of about ten cents a meal. From that, you can easily calculate they are both efficient and big, very big. For a long time, they collected left-over food from restaurants and caterers and gave it to poor folks in shelters. But that was before someone had the brilliant idea to hire an executive director who had formerly been an executive in the supermarket business, rather than a dietician or a social worker or a retired lawyer. Nowadays, Philabundance still takes the calls from restaurants and caterers but refers them to some local food bank to do the pickup. And it doesn't distribute food to the poor itself, instead, it helps new churches get established in poverty regions, showing them how to organize and run food distribution agencies, or stores or kitchens.

|

| Philabundance |

Philabundance is going for big deliveries, and cutting the big costs in the food chain. Clark knew who was dumping the food, by the carload, and it wasn't restaurants. He organized a system of collecting bread from major bakeries, fruit from major importers, meat from the food distribution center -- in carload lots. Someone from inside the food distribution system knows how tightly organized the shelf life is, and if he can get bananas to his eaters in five days, he can have them free from people who absolutely must have eleven days to get them through a delivery chain of fussy people picking and choosing what is on display before they buy. In a market system where food is routinely discarded in order to maintain stable prices (ask any farmer), someone who knows what he is doing can really get some bargains for the poor. You have to know about taxes, too. Donations of food are not just deductible at cost, but at cost plus half of the normal mark-up. A great many of the cargo containers arrive at Philabundance warehouse, unopened because they arrived too late for the weekend buying rush, and would otherwise have to be sold at low Monday prices. There's a lot to learn about this business.

|

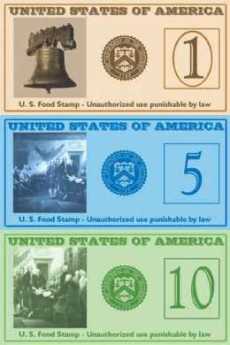

| Food stamps |

Food stamps might be a better way to distribute food to the poor, but big cities have an acute shortage of supermarkets, as you soon learn if you live there. New York has an extensive system of neighborhood mom and pop groceries, but Philadelphia doesn't. It's hard to know whether mom and pop stores can't survive in Philadelphia for some reason, or whether New York's notoriously political-legal system is slanted in favor of them, along with rent-controlled apartments on Park Avenue. Supermarkets in center city are hampered by the underlying supermarket the assumption that there will be ample place to park a car at both ends of the shopping trip. Since it is easy to pay $300 a month to park in center city, and even then you find the attendant may have parked someone else in the aisles, you can see that the supermarket idea, which largely developed in Philadelphia in the first place, is more popular in the suburbs.

So, anyway if you are going to throw food away you might as well give it to the poor and get a tax deduction. And if you are going to give food to the poor, you might as well be efficient about it. No doubt there will be some who raise the point that making things free for the poor will attract more of them into the region, raising Medicaid costs and so on. Maybe that's why Bill Clark draws so little attention to the splendid job he is doing, but if so, we really must betray him.

Slum Creation and Urban Sprawl

|

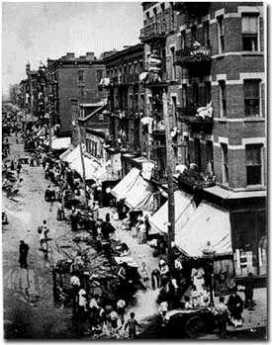

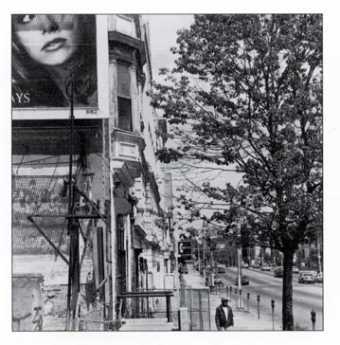

| North Philly |

Slum creation, while occasionally deliberate, is most typically caused by an area's abandonment by previous owners, at lower prices, to bargain hunters. When a large employer moves or closes, the employees seek work elsewhere and sell their houses for what they can get. When the influx of new ethnic groups threatens to weaken real estate prices, panic may be created that waiting too long to sell may find the property worthless; nobody wants to be the last one out the door. During the 20th Century, the driving force in Philadelphia was the flight to the suburbs by people who found a better value in suburban schools, shops, and neighborhoods. All of these processes create slums, almost invariably with a net loss of value in the community. Take a look at those deteriorating mansions on North Broad Street, where the Civil War millionaires used to live. In today's terms, they were once worth several million dollars apiece, but in today's real estate market, they are next to worthless. Value disappeared. The community as a whole is poorer than it was. From the Mayor's point of view, the area has lost its tax base.

|

| New Construction |

Of all these forces, the flight to the suburbs is probably the least destructive to the region, particularly if it is reasonably slow. Out in the suburbs, value is being created as cornfields turn into suburbia, and that added value must be set against the reduced value of the abandoned slum areas. Viewed from the Mayors' perspectives, however, we have a zero sum. The city loses its tax base, the suburbs gain, and local politics soon degenerate into warfare between the suburbs and the city. Not a nice situation, and it cries out for a new civic design. The city politicians have dreamed for a century of city-suburb consolidation, but Philadelphia tried that in 1850. It didn't cure the problem, and it may have created new problems. In any event, suburban politicians live and die on their anti-city rhetoric, and everybody's behavior in the Legislature deserves no kinder description than -- savage.

|

| Orange Station |

Because this issue has been the underlying theme of the Pennsylvania Legislature for two centuries, it repeatedly surfaces in ways that are surprising unless you understand the mechanics of suburban sprawl well enough to see the connection. For example, nowadays a real issue is the three-car family.

During the 19th Century, multi-acre estates spread out along the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad, with the coachman and horses taking plutocrats to the station. Smaller houses, for people who walked to the station, clustered nearby, but you didn't have to go very far from the station to find the gated estates. Suburban development spread out in linear and predictable fashion from the city, along the Main Line. The advent of the automobile freed commuters from the tyranny of railroad station orientation, and middle-class residents could flee the city to areas of the suburbs that were fairly far from the railroad and its stations. But not too far, because there was the problem of the lady of the house, who had to get to the stores. To free her up, the family had to have two cars in the garage. Suburban shopping malls helped her problem, somewhat, but the railroad station was still a magnet.

And then, the majority of married women became working wives, confronting the problem of kids getting to the confounded school. The highly questionable solution of giving the kids a collective car as soon as the oldest got a license, made the oldest kid proudly take the role the coachman used to have, and it caused a lot of teenage turmoil that need not be described here. The point to be stressed is that the three-car family sent home-building into cornfields that were not even close to the main road. Since land gets cheaper the further you get from the city, an economic incentive is created to enter uncongenial social environments, and adopt unexamined attitudes about the environment that are ultimately flatly contradictory.

When the kids leave home, the exurban pioneers no longer need the third car, and think about returning to city life. So far, however, they have been returning to Center City, not the residential neighborhoods they used to call home.

Police Athletic League

|

| pal |

T he Philadelphia chapter of the PAL is now almost sixty years old; that means its origins are to be found in the great industrial migrations and urban dislocations of World War II. Philadelphia has experienced many upsurges of crime in its long history, and almost without exception crime centers in new immigrant groups. Commentators on prison conditions over the centuries have always remarked on the over-representation of whatever is the most recent immigrant group among the inmates. Crimes related to recreational drugs may be an exception, just as crimes related to bootlegging were an exception during Prohibition. Or maybe not; perhaps issues of that sort merely affect the type of crime and the reason for committing it, while the criminals themselves continue to concentrate in the most recent immigrant population. It is merely to face the plain facts to notice that the war industries attracted large immigration to Philadelphia of African-Americans, so the recent-immigrant crime wave centered in them. There's actually hope in that if we keep calm about it. It means that crime can in time be expected to settle down, just as it did after the waves of immigration of Irish, Germans, and Scotch in earlier centuries. This wave of immigrants from the Southern states will surely be assimilated, too. Police records show that most crimes are committed by teenagers, committed between 3 PM and 9 PM. The aim of the Police Athletic League is therefore clear: keep teenagers busy and off the streets between 1 PM and 9 PM. The 27 centers of PAL, with nearly 30,000 participants between age 6 to 18, have a budget of over $2 million a year, all privately donated. The contribution of the City Government is to supply police officers to staff the centers, and that is an unexpectedly important thing to do. One might suppose hostile teenagers would be turned off by the presence of "the man", the stormtrooper of the enemy, and perhaps some are. But the presence of police in every center means that PAL is safe when very little else is safe for lower class teenagers. And of course, it is important for teenagers to learn that cops are people. Lots of cops are nice guys who will help you. Lots of cops used to be members of PAL, themselves. A men's luncheon club to which I belong donates the profits from a weekly lottery to PAL, and consequently, a speaker from the League is sent to thank us by giving a talk once a year. The Police Athletic League is clearly evolving. It started out with only programs in boxing and basketball, rather obvious choices. But now, the example of Tiger Woods has stimulated a great deal of interest in golf, which takes place on the loan of time at five local golf courses. Many famous civic leaders are involved in the governance of this organization, and recently the Lend fest family has been especially generous. You can look forward to a large well equipped PAL center soon, at Luzerne and 12th Streets, based on their generosity. It will have, among other things, squash courts, no less. Squash started out as a game in debtor's prison, but it currently has the image of upper-crust exclusivity. It's important to do things like that. And the activities of PAL have further evolved away from prize-fighting into computer classes. A popular new development has been a mathematics competition. It would go too far to say that PAL has saved a whole generation from living the life of the streets. But it's making progress which is very heartening to see.

Settlement Music School

|

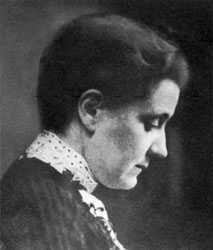

| Jane Adams |

The Settlement Music School has six branches, fifteen thousand current students, an $8 million budget, and three hundred thousand alumni. It tells you something about Philadelphia that an organization this large can exist for 98 years, and yet remain almost invisible. So let's tell a few things about it.

The settlement movement began in England around 1880, and was brought to America by a Quaker lady named Jane Addams. Her most famous settlement was called Hull House, in Chicago. Jane Addams seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt at the Progressive Party convention, and was active in the formation of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, as well as the American Civil Liberties Union. She was a prominent suffragette, and as a Quaker, it might be expected that she was an outspoken pacifist. Remember, what we are talking about here is music.

|

| tenement districts |

Settlements were what nice upper-class ladies called the tenement districts, and a settlement House was a center for activist women to go help the immigrant groups typically found there. Since there is obviously a lot of difference in what needs to be done to help recent ex-slaves, Italian and Jewish immigrants, and all the different ethnic clusters, the Settlement movement is an archipelago of very different forms of social work. One of the ways to appeal to different groups is through the teaching of music, and the teaching on expensive bulky instruments like pianos is quite naturally shared in a school building. While it is true that a couple of Settlement students are admitted to the musical big time at Curtis Institute every year, only a small proportion of Settlement students go on to musical careers. The three most famous musical alumni of the Philadelphia Settlement Music School were Chubby Checker, who invented a dance called the Twist, Albert Einstein. who played the violin in various chamber groups, and former Mayor Frank Rizzo, who learned to play the clarinet.

The mission of the Settlement School has gradually become the spreading of musical appreciation, especially among "the masses", and it measures its success in the size of its audiences rather than by occupying the center of the stage. This function is readily thrust off on them by the eagerness of public school boards to cut expenses, although the School is scarcely in a financial position to go all the way and assume the role of teaching music classes to 250 public schools. Nevertheless, when financial stringency forces the school board to cut expenses, their choice between a music teacher and a football coach is no choice at all. At that moment, a free-standing music appreciation school ceases to be a competitor and becomes a safety valve. When you hear the Settlement School is in need of money, you are likely being told about stringency in the public school budget.

Although the tuition is quite inexpensive for a music school, the students collectively contribute about half of the annual budget. The rest comes mostly from private charity. You really can't expect cutting edge innovation from school children or endowed charities. But somehow this school leaves you with an impression of big missed opportunity in the truly American forms of music like jazz and folk singing. Symphony orchestra was invented in Vienna and flourishes there, so it has a faintly foreign air to it. It's not completely surprising that both the sponsors and the subjects of Americanization for the Slums are hesitant to promote symphonic role models, while the sponsors at least are a little lost in the world of Rock. Not surprising, but something of a pity.

James A. Michener (1907-1997)

|

| James A. Michener |

James Michener seemed headed for a recognizably Quaker life until show business rearranged his moorings. He was raised as a foundling by Mabel Michener of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, under circumstances that were very plain and poor. Many of his biographers have referred to his boyhood poverty as a defining influence, but they seem to have very little familiarity with Quakers. When the time came, this obviously very bright lad was offered a full scholarship to Swarthmore College, graduated summa cum laude, went on to teach at the George School and Hill Schools after fellowships at the British Museum. And then World War II came along, where he was almost but not exactly a conscientious objector; he enlisted in the Navy with the understanding he would not fight.

While in the Pacific, he had unusual opportunities to see the War from different angles, and wrote little short stories about it. Putting them together, he came back after the War with Tales of the South Pacific. Much of the emphasis was on racial relationships, the Naval Nurse who married a French planter, the upper-class Lieutenant (shades of the Hill School) who had a hopeless affair with a local native girl that was engineered by her ambitious mother, as central characters. Michener himself married a Japanese American, Mari Yoriko Sabusawa, whose family had been interned during the War. There are distinctly Quaker themes running through this story.

And then his book won a Pulitzer Prize, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein made it into a Broadway musical hit, then a movie emerged. The simple Quaker life was then struck by the Tsunami of Broadway, Hollywood, show biz and enormous unexpected wealth. Just to imagine this simple Bucks County schoolteacher in the same room with Josh Logan the play doctor is to see the immovable object being tested by the irresistible force. Michener retreated into an impregnable fortress of work. He produced forty books, traveled incessantly, ran for Congress unsuccessfully, and was a member of many national commissions on a remarkably diverse range of topics. Although he lived his life in a simple Doylestown tract house, he gave away more than $100 million to various charities and educational institutions.

In his 91st year, he was on chronic renal dialysis. He finally told the doctors to turn it off.

Stephen Girard and Religion

|

| Girard College |

In 1950, an elderly retired gentleman named Witherbee paid me a visit when I was temporarily covering practice for a doctor in Woodbury, New Jersey, in locum tenens, as we say. His medical problem was easily tended, and we chatted.

He told me that he had attended Harvard Divinity School many years before, and one day was about to graduate as an ordained minister. His family and many other proud families were gathered on folding chairs on the lawn in Cambridge to watch the graduation ceremonies. The graduates were called up one by one, in alphabetic order.

Since Witherbee is at the end of the alphabet, he had a lot of time to think over the significance of what the members of his class were doing. In time, thinking over the personal defects of each classmate who preceded him, he became overwhelmed with a personal question. "How can I tell others how to behave, when I don't know how to behave, myself?"

And so, when his turn came, his name was called out, and he rose in his seat. "I decline to graduate."

The consternation of his family can be imagined, along with the stir in the audience, the astonished face of the Dean, and his own confusion about the uproar he had just caused. But although the die was cast, and the action a final one, it had a surprising outcome. The next day, he received a telegram from the Girard College in Philadelphia, inviting him to be considered for the position of Director of Religious Studies. It seems that Stephen Girard had provided in his will that no ordained minister might set foot within the walls of Girard College, and yet they felt they needed someone to oversee the religious study. Witherbee was perfect: he had the credentials, but he did not have the ordination curse.

And so he happily remained in that capacity for the rest of his employed life.

REFERENCES

| Girard College It's Semi Centennial of Girard College: George P. Rupp ASIN: B000TNER1G | Amazon |

The First and Oldest Hospital in America

|

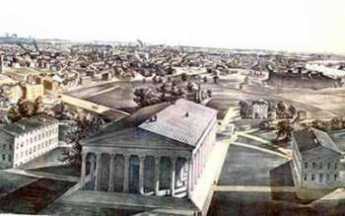

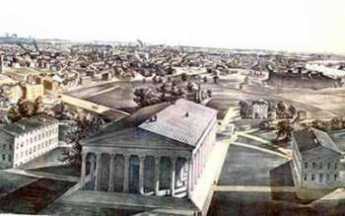

| South East Prospect of Pennsylvania Hospital |

There is a painting of the region around 8th and Spruce Streets in the 1750s, depicting a pasture, with cows, and three or four buildings between 8th and 13th Streets. When the Pennsylvania Hospital moved there in 1755 from its temporary location in a house located a block from Independence Hall, there were complaints that it was now located so far out in the woods that it was difficult and dangerous to go there. Still another description of the area is evoked by the provision which the Penn family placed in the deed of gift of the land, strictly forbidding the use of the land as a tannery. Tanneries have always been notorious for giving off noxious odors, so most people wanted them to be somewhere else, anywhere else. In any event, the main activity of Penn's "green country town" at that time was concentrated closer to the Delaware River, and the nation's first hospital was definitely placed in the outskirts. Two blocks further West the almshouse was already in place, but not much else. We are told that Benjamin Franklin had flown his Famous Kite at 9th and Chestnut, using a barn there to store his materials. It might be recalled that the population of Philadelphia, although the second largest English-speaking city in the world, was only about twenty-five thousand inhabitants at the time of the Revolution, and in 1751 was even smaller.

In any event, the first and oldest hospital in America was built on 8th Street between Spruce and Pine, and the Eighteenth Century buildings on Pine Street still present a breathtaking view at any season, but particularly in May when the azaleas are in bloom, and fragrance from the flowering magnolias fills the evening atmosphere for blocks around. Although some people today mistake the Pennsylvania Hospital for a state hospital, it was founded in the reign of George II, decades before there was such a thing as the State of Pennsylvania. The Cornerstone was laid by Benjamin Franklin, with full Masonic rites. Most doctors regard a hospital as a mere workshop, but the affection with which many Pennsylvania physicians regarded their special hospital is indicated by the number who have requested that their ashes be buried in the garden.

For two hundred years, beginning with the first American resident physician Jacob Ehrenzeller, the interns and residents were paid no salary, so they had to live on the grounds. An Internet was just that, interned within the four walls for at least two years. Because the resident physicians had no money, they stayed in the hospital at night and on weekends, playing cards and swapping stories. The hospital was home for them, as it was for the student nurses, likewise unpaid but more strictly confined and supervised. This penury seemed acceptable because the patients were mostly charity ward patients, otherwise unable to pay for their own care. Ehrenzeller finished his medical apprenticeship and went to practice for many decades in the farm country of Chester County, but gradually upper-class Philadelphia moved from 4th Street westward to and beyond the hospital, and two of the richest men in American history, Morris and Biddle, had houses within a block of the hospital, although Morris never lived in his house, having more pressing matters in debtor's prison. Therefore, later resident physicians at the hospital had the potential of setting up a private practice in the area and becoming society doctors as well as academically prominent ones. Being a charity hospital in a rich neighborhood created the potential for volunteer work by the town aristocrats and large bequests for charity. The British housed their wounded in the hospital during the Revolutionary War and shot deserters against the red brick wall of the small cemetery to the north. A century later, there were a couple of dozen rooms for private patients in the hospital for the convenience of the doctors and the neighbors, but everyone else was a charity patient. And a century after that, the hospital still did not have an accounting department to collect bills and tended to regard people who asked for a bill as a nuisance. Benjamin Franklin is regarded as the Founder of the hospital, and his autobiography famously describes how he fast-talked the legislature into matching the donations of the public, not mentioning to them that he had already collected enough promises to see the project through. This seems in character; Franklin's biographer Edmond Morgan summed up that, "Franklin doesn't tell us everything, but what he does tell us, is straight." The idea for the hospital was that of Dr. Thomas Bond, whose house is now a bed and breakfast on Second Street, but it was characteristic of Franklin to be the secretary of the first board of managers of the hospital. In Quaker tradition, the clerk of a meeting is the person who really runs the show. It thus comes about that the minutes of the founding board were recorded in Franklin's own handwriting, among them the purpose of the institution, which is to care for the Sick Poor, and if there is room, for Those Who can pay. This tradition and this method of operation continued until the advent in 1965 of Medicare when charity care was displaced by concepts which the nation had decided were better. The Pennsylvania Hospital was not only the first hospital but for many decades it was the only hospital in America. Its traditions, sometimes quaint and sometimes glorious, cast a long shadow on American medicine.

REFERENCES

| America's First Hospital: The Pennsylvania Hospital 1751-1841 William Henry Williams Ph.D. ISBN-10: 0910702020 | Amazon |

Keeping Lunaticks Off the Streets

|

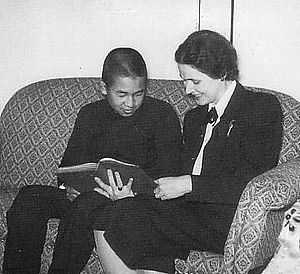

| Prince Akihito and Elizabeth Gray Vining |

Two Quaker ladies at the AFSC made a totally unique contribution when a request was received to provide a suitable tutor for the Crown Prince, now Emperor. He didn't convert to Christianity, but he later married a Christian, and you can be sure he got a plenty good dose of Quaker style and belief from Elizabeth Gray Vining. This tall, strikingly handsome Philadelphia woman had Bryn Mawr written all over her and turned heads whenever she entered a room. When she went back home, she was followed as a tutor for seven years by, guess who, Esther Rhoads who by then was the director of the Tokyo girls school. It remains to be seen, of course, what the final outcome of this deeply emotional situation will prove to have been. At the moment, the main sufferer seems to be the immensely talented American-educated woman who married the Emperor. But we will see; these are all powerful women in a very quiet way, unaccustomed to losing. One wishes the royal family all the best in their sometimes difficult position.

And then the Service Committee did its work in Vietnam, in Iraq, in Zimbabwe, and Somalia on the unpopular side, in every case. There are stories of venturing into war zones with hundred-dollar bills scotch-taped to their torso, where every fifty feet there was someone who would cut your throat for a dime. One worker in Laos entertained a group of us tourists with tales of living for weeks with nothing to eat but grasshoppers and cockroaches. Dangerous, unpopular, and uncomfortable. It sounds like a wonderful outlet for someone who is a perpetual rebel without a cause, but if you can find one of those at the Service Committee, you must have done a lot of looking.

The Service Committee, like the Quaker school system, is mostly run by non-Quaker staff. That means that neither of them exactly speaks for the religion itself. This little religious group of 12,000 members is stretched thin to provide a vastly greater world influence than its numbers imply. Hidden in the secrets of the group is an enduring ability to attract sincere non-member adherents to their work. And a quiet watchfulness to avoid losing control to any wandering rebels without a cause.

REFERENCES

| Window for the Crown Prince: Akihito of Japan, Elizabeth Gray Vining ISBN-13: 978-0804816045 | Amazon |

Block Captains

|

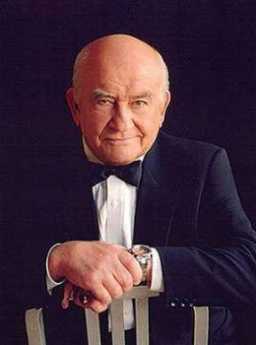

| Ed Asner |

A block captain is not a ward leader, at least not most of the time. The block leaders of Philadelphia are mostly self-appointed, de facto captains, and yes, they are mostly middle-aged black ladies. Their attitude is that politicians are there to serve the community, not the other way around. At a recent meeting, the leader of the Block Captain's Association called out to the nodding, approving group, "Call your councilman. We elect those people, put 'em to work!"

This enthusiastic group of several hundred grass-roots leaders meets several times a year in, of all places, the hallowed auditorium of the Philadelphia County Medical Society, but doctors are not running this show. Nor is the City Health Department, nor the Department of Streets, nor the various mental health and social service agencies that send representatives. The federal government expressed considerable gratitude in being able to address this group because their new Medicare prescription card was so terribly hard to explain (i.e. it was terribly hard to understand). The genius of the block captain movement is that it appoints leaders to understand what the establishment is trying to say, and then figures out a way to say it. You can make free flu shots available, even take them to the home or workplace, but most people won't accept them unless it is explained by someone they trust. Dead birds don't spread disease, mosquitoes do, but that really sounds a little unlikely. To believe that, you first need the word of a respected local leader. The U.S. Army is built around its sergeants, in the same way. That's in fact how things work at every social level, but in Philadelphia's black communities, it is finally becoming organized. For example, they like pamphlets. Pamphlets are what give sergeants credibility back in the neighborhood.

Success has a thousand fathers, failure is an orphan, so it's now hard to know who started this. Eve Asner, the sister of Ed Asner the movie star, can claim credit for starting a group called Philadelphia More Beautiful, dedicated to cleaning up the messes of the slums, and applying social pressures of a loud and effective sort to irresponsible neighbors. And then, along came the Deputy Health Commissioner Larry Robinson with HEAT. During a hot summer, it was possible for a hundred children and old folks to die of heat prostration because they were confused by dehydration and did things which made matters worse for themselves. The block captains were ideally situated to know who was in danger, who hadn't appeared outside in a day or two, and thus who might need to be forced to drink water or go to an air-conditioned movie. Training the block captains to recognize the signs of trouble fit nicely into the Health Department's ability to measure results with computers. Last year, only seven people died of heat prostration, and everybody knows whose block they lived in.

The Medical Society pays for everybody's lunch at the block captain's meeting, and it is a calculated policy. Every doctor knows how useless it is to talk in terms of calories, carbohydrates, high unsaturated fat content, and water-soluble vitamins. Pamphlets help, but what really works is to serve the block captains a lunch and tell them, now this is what we're talking about. Heaven only knows how that gets translated back in the neighborhood, but surely the first step is to give the block captain an unmistakable message. The Medicare bureaucrat looked visibly relieved when her painfully convoluted explanation of the Medicare prescription card was reduced to about two sentences by questioners in the audience: If you have Medicaid coverage, forget it. If you don't, that card's worth about $600. And this here pamphlet proves I know what I'm talking about.

There did not seem to be a scrap of ideology or power hunger or self-serving -- the usual hallmarks of politics as we commonly observe it. The over-riding principle on which these highly disparate groups are operating together is, pick a problem, and solve it.

Charitable Immunity: An Underestimated Revolution

|

| Percent |

Until 1939, there was a legal doctrine of Charitable Immunity, which universally shielded hospitals and other charitable institutions from negligence lawsuits. No doubt the underlying reasoning was that charities possess limited funds for unlimited demands, and must be forgiven for imperfect compromises in the face of scarcity. To threaten them in court for falling short of perfection might drive charitable efforts away entirely. Since many professionals donated their services to the common effort, there was some spill-over protection for individual professionals, but this centuries-old doctrine applied to institutions more than individuals. There can be little doubt that improved financing of hospitals by health insurance and government programs resulted in both higher standards and lessened public tolerance for imperfection. One might say that twentieth century America decided it could afford better care, supplied the money for it, and expected to see results. It might also be commented that Medicare and Medicaid were significantly overfunded at first, but with time have become painfully underfunded, particularly by Medicaid.

The New Hampshire Supreme Court, against all prevailing doctrine of the time, held in 1939 that hospitals in that state should no longer be broadly shielded from liability by the doctrine of charitable immunity. By 1991, this new legal view had extended to the point where the Pennsylvania Supreme Court felt a need to define Corporate Negligence, emphasizing a hospital's duty to ensure a patient's safety while in the hospital. The court specified the duty to provide safe facilities, to select and retain only competent physicians, to oversee all persons who practice medicine within the walls, and to formulate and enforce adequate rules of behavior. Looking back, legal scholars point to two particularly significant intervening court decisions. In 1957, eight years before Medicare, the New York Court of Appeals declared that to say the doctor is the captain of the ship, acting on his own responsibility, no longer fits the facts. The court bore down hard on the existence of salaried physicians, and the illuminating fact that hospitals were openly sending out bills for medical services. In 1973, the Superior Court of Delaware deliberately and consciously extended the New York doctrine from salaried physicians to independent contractors working within the hospital. But independent contractors are still working for pay; the courts have been more hesitant to extend the idea of corporate control to volunteers who work without payment of any sort. But the movement is in that direction, so it is increasingly difficult to find anyone to volunteer. The American instinct to volunteer is still very great, as the response in 2005 to the South Asian tidal wave demonstrated, with relief agencies forced to send out appeals for the flood of volunteers please to stay home. But the central fact remains that the original premise was limited resources for unlimited needs; Medicare and Medicaid temporarily made it seem resources would be infinite, so why should an injured patient forgive a volunteer. As it becomes increasingly evident that the 1965 federal promises of infinite support are unsustainable, the invalidation of charitable immunity deserves to be re-examined.

The 1973 date of the Delaware decision is probably significant because that was a time of abandonment of malpractice coverage by insurance companies. If you couldn't sue doctors, and you feel you must sue somebody, plaintiffs were in effect told to sue the hospitals. With charitable immunity, hospitals didn't carry insurance, but they immediately searched for it. And thus, a bigger, far juicier deep pocket was created. Physician malpractice premiums, outside of California, were approximately $100 a year. Those rates proved to be far too low. The temporary collapse and disappearance of malpractice insurance companies took place in 1975. It is very hard to blame the actuaries of a malpractice company in say, California, for failing to take fully into account a decision by the Superior Court of Delaware in their premium-setting.

Before this revolutionary upheaval, a volunteer chief of medical staff was (nominally) in charge of every mistake made by any employee, and that was pretty unfair if he got sued. The captain of the ship idea devolved to department heads, or perhaps just the responsible surgeon in the operating room. If the scrub nurse counted sponges wrong and left one behind in the patient, the responsibility passed upward to one of these captains or sub captains. The manifest unfairness of demanding damages from someone six or more steps removed from the incident, particularly one who had a largely honorary title and no real control, exercised a restraint of sorts on lawsuits. Once the blame was shifted to a nebulous legal entity known as the corporation, blameless blame transformed into a corporate financial liability. The average size of awards against institutions escalated upward, raising the size of claims for similar injuries against individual physicians. Add to that the growing fact that hospital revenues are almost exclusively derived from insurance third parties, and thus the premiums for hospital insurance could only come from insurance as an automatic pass-through. Disaster looms if the intermediate parties have nothing to lose, and the public pays all the cost through health insurance or taxes. None of this adversary system, including the whole tort system and the whole malpractice insurance system, was designed to cope with a financially pain-free defense posture. One paradox of the situation is that the admirers of the plaintiff viewpoint are typically also sympathizers with universal health insurance. The two are utterly incompatible under any set of proposals, so far offered.

If matters had stopped at that point, well, it's only money. But obviously, the counter pressure on health insurers to hold down these costs was inevitable. Hospitals were practically under court order to make rules (the hospital associations would be happy to construct a model set of rules) and enforce them on their attending physicians, to pay professionals salaries wherever possible as a time-tested means of encouraging obedience, and to reorganize themselves as corporations practicing medicine rather than hotels providing space and services. (There are legal barriers, of course. Numerous state constitutions awkwardly state "No person may practice medicine in this state without a license so to do.") Needless to say, physicians resisted this trend toward the corporate practice of medicine, even though its early forms only took the shape of placing the hospital lawyer in charge of conferences about "risk" prevention. Since the lawyer knew very little about the topic, the discussion tends to focus on horror stories of suits that were lost or are in litigation.

This struggle between physicians and administrators for control of the hospital, using malpractice as a debating point, is bad enough. Far worse is the slanting of the system of actual medical organization of the staff. Hospitals now often have thousands of nurses and hundreds of doctors, each reporting upward within two guild structures. You would think the chief of surgery would have a lot to say about the selection of the nursing supervisor in the operating room, but heaven forbid. Nurses are hired and fired through the nursing hierarchy, not the department hierarchy which would cross guild lines. It's sometimes hard to say who is on which side of this issue, and probably everybody is on both sides, sufficient to paralyze rational discussion. Everybody involved wants to diffuse blame for an error through the whole organization, and so resists having responsibility conferred in any consistent way. The chief of surgery, for example, is ambivalent about whether he wants nursing errors legally passed back to him, and thus tends to retreat from asserting himself. It can sometimes be hard to specify the ways this chaos expresses itself in poor quality or higher costs, but it would certainly be remarkable if it didn't.

House that Love Built: Ronald McDonald of Philadelphia

Kim Hill had the misfortune to develop leukemia, but the great luck to have Fred Hill of the Philadelphia Eagles football team for a father. Driven by gratitude for the treatment at St. Christopher's Hospital for Children

|

| Audrey Evans |

Fred demanded to be told what he could do and was referred to Dr. Audrey Evans. This world-famous pediatric oncologist was well known for her philanthropic activities and had frequently expressed the need for a temporary residence for families of children needing protracted medical treatments. Young children have young parents, whose savings are soon exhausted by travel, hotel and other non-insured costs related to a seriously sick child. The Hills had just been through such an experience and grasped the problem immediately, adding to it the discomfort and loneliness of families in such a situation. Fred Hill quickly enlisted the enthusiastic support of the whole professional football organization, and Jim Murray the Eagles' general manager recruited Don Tuckerman from their advertising agency, who got to Ed Rensi, the regional manager of McDonald's. Together, they got the project financed and started with a seven-bed facility near Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

|

| Fred Hall |

In 25 years, the Philadelphia Ronald McDonald House has grown to a capacity of 44 families, in a century-old mansion at 39th and Chestnut Streets filled with Mercer tiles and the like. The operation uses eighteen volunteers at all times, runs two jitney buses, and is one huge teeming family home for people confronting a common issue, supporting each other through a wrenching emotional experience. Although it actually costs about $65 a day per family, the charge is $15 and over half of the clients cannot afford even that. Although an effort is made to have family cooking, the McDonald's restaurant chain supplies 20% of the budget along with generous help with exigencies and in-kind assistance with such things as clowns for the entertainment program, birthdays and the like. Although McDonalds's is probably the world's premier franchising corporation, every one of the 300 worldwide Ronald McDonald Houses is an independent local organization, run without a central headquarters or any sort of standards-setting and the like. Every one of the other 299 Houses got the idea from Philadelphia but proceeds in its own way. Philadelphia created it, but Philadelphia does not own the idea.

In this connection, it is probably worth reflecting on the history of this topic. When Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond started the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751 at Eighth and Spruce Streets, it was the custom to be diagnosed, treated, be born and to die in your own house. The unique perception behind the nation's first hospital was that poor people generally did not have home facilities that were adequate to support home care. In Franklin's own handwriting the purpose of the Pennsylvania Hospital was stated to be "for the sick poor, and if there is room, for those who can pay." It was understood that poor sick people needed a place to take care of them, not merely for their surgery and overwhelming illness,

<but for convalescence and rehabilitation as well. Two centuries later, in the first thrill of founding the Medicare and Medicaid programs, it was imagined that things would remain exactly the same, only paid for by the Government. But after four or five years, it became abundantly clear that it was far too expensive to use hospitals in that way. The very act of federally paying for the program undermined its volunteer spirit, raised its mandated standards, and made it financially unsustainable. And so, although the 1965 Amendments to the Social Security Act insisted, and still pretend, that no change was to be made to the delivery of care, the delivery of care simply had to be changed. Not only was domiciliary and custodial care to be excluded, but heroic efforts were to be made to reduce the length of stay in the hospital to what would once have been regarded as special intensive care. In effect, if a type of service could normally be handled at home by non-indigent people, it was to be prohibited for everybody. Since the cost of care in hospital has continued to escalate far in excess of the cost of living, it seems unlikely we will ever go back to the days of rest and in-hospital recuperation.

So, just as Dr. Bond recognized the problem and went to Ben Franklin to handle the philanthropy, Dr. Evans had the idea and Fred Hill made it work. Around the Ronald McDonald house, the idea is frequently heard expressed that every hospital needs such a place nearby, for people of all ages. Perhaps that is workable, but it offhand seems more likely that Retirement Villages, so-called CCRC, will be called on to supply this badly needed service, at least for senior citizens. And that what we now call hospitals will evolve into the scientific "focused factories" so popular in the minds at the Harvard Business School.

Slavery: If This be done well, What is done evil?

|

| Francis Daniel Pastorius |

The Declaration of the German Friends of Germantown, Against Slavery, in 1688.

These are the reasons why we are against the traffic of men's body, as followeth:

Is there any that would be done or handled in this manner? viz.: to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? How fearful and faint-hearted are many at sea, when they see a stranger vessel, being afraid it should be a Turk, and they should be taken, and sold for slaves in Turkey. Now, what is this better done, than Turks do? Yea, rather it is worse for them, which say they are Christians; for we hear that the most part of such negers is brought hither against their will and consent and that many of them are stolen. Now though they are black, we cannot conceive there is more liberty to have them, slaves, as [than] it is to have other white ones. There is a saying , that we shall do to all men like as we will be done [to] ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent, or color they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, which is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of the body, except evil-doers, which is another case. But to bring men hither, or to rob, [steal] and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe, there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed which are of black color. And we who know others, separating wives from their husbands, and giving them to others: and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! do consider well this thing, you who do it, if you would be done in this manner--and if it is done according to Christianity! You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe when they hear of [it,] that the Quakers do here handler men as they handle there the cattle. And for that reason, some have no mind or inclination to come hither. And who shall maintain this your cause, or plead for it? Truly, we cannot do so, except you shall inform us better hereof, viz,: That Christians have liberty to practice these things, Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse, towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating husbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at, [by]; therefore, we contradict [oppose], and are against this traffic of men's body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid purchasing such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing, if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of the hands of the robbers, and set free as in Europe. Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead, it hath now a bad one, for this sake, in other countries. Especially whereas the Europeans are desirous to know in what manner the Quakers do rule in their province; and most of them do look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil?

If once these slaves ( which they say are so wicked and stubborn men,) should join themselves--fight for their freedom, and handle their masters and mistresses, as they did handle them before; will these masters and mistresses take the sword at hand and war against these poor slaves, like, as we are able to believe, some will not refuse to do? Or, have these poor negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?

Now consider well this thing, if it is good or bad. And in case you find it to be good to handle these blacks in that manner, we desire and require you hereby lovingly, that may inform us herein, which at this time never was done, viz., that Christians have such a liberty to do so. To this end, we shall be satisfied on this point, and satisfy likewise our good friends and acquaintances in our native country, to whom it is a terror, or fearful thing, that men should be handled so in Pennsylvania.

This is from our meeting at Germantown, held ye 18th of the 2nd month, 1668, to be delivered to the monthly meeting at Richard Worrell's.

Garret Henderich

Derick op de Graeff

Francis Daniel Pastorius

Abram op de Graeff.***

At our Monthly meeting, at Dublin, ye 30th 2d mo., 1688, we have inspected ye matter, above mentioned, and considered of it, we find it so weighty that we think it not expedient for us to meddle with it here, but do rather commit it to ye consideration of ye quarterly meeting; ye tenor of it is related to ye truth.On behalf of ye monthly meeting,

Jo. Hart.

***

This above mentioned was read in our quarterly meeting, at Philadelphia, the 4th of ye 4th mo., '88, and was from thence recommended to the yearly meeting, and the above said Derick, and the other two mentioned therein, to present the same to ye above said meetings, it is a thing of too great a weight for this meeting to determine.Signed by order of ye meeting.

Anthony Morris

Insuring the Uninsured is Not Entirely a Health Issue

|

| James Madison |

shrewdly observed that people could and would restrain state taxation by moving to a neighboring state. The founding fathers never contemplated health insurance or Medicaid, of course, but the same principle applies there in reverse. If one state gets too generous with health and welfare benefits, people in neighboring states will nowadays hear of it and get on a bus to relocate advantageously. A flood of new low-income citizens may or may not be what a particular state wants, depending on local economic conditions.

For example during the great depression of the 1930s,

|

| The Great Depression |

Unemployment was so widespread that no state dared attract still more of it with generous welfare benefits. On the other hand, during the recovery period that followed World War II, the industrial northern states definitely did attract cheap labor from the southern states, using better health care, freely available, along with better unemployment benefits. In each case, employers alternate between wanting cheap labor or low taxes, while labor representatives relax or toughen their resistance to the cheap competition. Politicians are always looking for the argument that carries the most votes. If you want to understand the persistence of employer-based health insurance alongside unobtainable health insurance for others, look into this trio of motivations.

While it's true state legislatures must tend to the infrastructure, crime conditions and education, they can in the main be regarded as debating societies between employers and labor. There is some, but not much, the difference between Republicans and Democrats on the Medicaid issue. A Democratic Governor will welcome an influx of low-income voters who will normally vote for his party, but labor unions will soon remind him that enough is enough. A Republican Governor will gladly supply cheap labor for the state's employers until rising taxes bring an end to his support. Since the financial stability of the local hospital can be badly jarred by the instability of Medicaid payments, doctors soon get annoyed with the misalignment between state motives and the welfare of their patients. It is not much of an exaggeration, that state coffers might be overflowing with the surplus, but the budget of Medicaid will not rise a penny if it would attract poverty migrants from neighboring states during a period of high unemployment.

The obvious solution is a federal one, imposing uniform standards. But think that over a little before you jump at it. If the federal government pays all of Medicaid costs, it is going to want to administer the program. All states resist that idea, more so if local and federal political domination is in conflict. Small states will universally be fearful of being overwhelmed by large neighbors, particularly when they have achieved advantageous niches. The disastrous condition of the auto industry might persuade Michigan to agree, but Tennessee and other states with Japanese car plants might disagree. As you get close to the border of large states, hospitals near the border can often attract many patients from the other state; strange political bedfellows can link arms in Congress when you might not expect it.

None of this, absolutely none of it, has to do directly with medical care. But the quality of health care is strongly affected, and doctors are sick of hearing about poor sick folks when the real issue is labor availability. The voice is Jacob's voice, but the hand -- is the hand of Esau.

Unequal Health in an Unequal World

|

| Sir Michael Marmont |

In 2007, the Sonia Isard Lecture was delivered at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia by Professor Sir Michael Marmot on the topic of Health in an Unequal World . Sir Michael is the Director of the International Institute for Science and Health, and MRC Research Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health, at University College, London.

His starting point is the commonly accepted view that the richer you are, the better your health. The life expectancy of the poorest level of society is almost everywhere seen to be shorter than the local average. In less developed countries and in children, the excess mortality is concentrated in infectious diseases. However, in more affluent nations, it is obesity, diabetes, hypertension which seems to account for it. Regardless of the cause, the common denominator everywhere is poverty, which leads to a general opinion that the alleviation of poverty contains the solution to the health gradient. There is even another logical presumption, that improved health care will directly remedy the problem, without necessarily addressing a more daunting obstacle, the elimination of poverty. Although the provision of equal access to quality health care may be almost more than we can accomplish, in this analysis of causes, it is a short-cut.

Sir Michael is not so sure. Great Britain has had a national health service for fifty years, but it is still clear to British physicians that the class distinction persists in health if not in health care. Mortality statistics confirm the professional opinion. The conclusion is general that the British health system must be flawed, or underfunded, or poorly run. Not necessarily correct, not necessarily correct. Buried in a mountain of data from the Whitehall Studies of British civil servants, Dr. Marmot teased out the fact that a striking inverse gradient of mortality and morbidity existed in a highly educated group that had essentially equal health care and, while not rich were certainly not poor. The gradient persisted at all levels; the higher you rose in the bureaucracy, the longer you were destined to live after retirement.

Evidently a huge amount of statistical work followed this insight, confirming its thesis in a wide variety of situations. The caste system in India provided a confirming example that was unrelated to education or occupational strivings. Marmot's observation is a gradual gradient, not a two-part, either/or. Not rich versus poor, but richer versus less-rich, less-rich versus even-less rich. Every occupational, social or financial step up makes you live a little longer.

I wish he had stopped there. But the pressure to explain has generated the hypothesis that what we are looking at maybe progressive degrees of empowerment. Others who have contemplated Professor Marmot's observations suggest it is due to progressive degrees of happiness. Sorry, but that's a little too touchy-feely for me. I don't know what empowerment is, or how to measure happiness. The monk in his cell may have achieved serenity, not necessarily happiness, certainly not empowerment. The prisoner in his cell has no serenity, happiness or empowerment. I prefer to believe it is premature to speculate publicly about the mechanisms which produce these observations.

Meanwhile, it seems to be true that if you aspire to be rich you may not become happy, but you will probably live longer. If you want to rise in the hierarchy and still live longer, you need not be afraid to strive. For at least a little while longer, that's going to have to suffice as a definition of wisdom.

Community Volunteers in Medicine

|

| Comm Volu In Medicine |

Mary Wirshup has a very different medical background from mine, but she's my kind of doctor. I couldn't help wishing, as she addressed our urban luncheon club, there could be thousands more like her, even while understanding more fully than she seems to, the reasons why doctors are driven from her behavior model. As we parted, it felt like saying a last goodbye to the Spartans marching to Thermopylae.

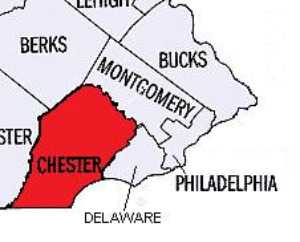

As 46,000 medically uninsured persons in Chester County get sickness and injuries, they know that a Federal Law prohibits a hospital accident room from refusing to see them, so ways are found to shunt patients to the CVIM free clinic, run by volunteers. This law is, in turn, a response to a government-created situation where a hospital which "accepts" patients must keep them. Any economics teacher can tell you that supply/demand issues are best addressed by price adjustment, so price controls in whatever guise lead to shortages. I must say I have little sympathy with the devious strategies which hospitals often employ to disguise their rejection of uninsured patients. At the same time, I know a lifeboat will sink if too many climbs aboard. Nevertheless, the semantic switch from lack of insurance to lack of care implies that only more insurance can surmount the barriers to care, which is absurd. For one thing, I know too many hospital administrators who are paid a million dollars a year, and one who is paid two million. And at least two health insurance executives are in the newspapers with a net worth over a billion -- yes, that's billion with a b. We have reached a point where reducing all physician income to zero would only reduce "healthcare" costs by 10%. As I look at Dr. Wirshup's modest clothing I can only surmise she plans to continue her modest living until she is 80 years old, after which her savings might see her out. Squeezing physician reimbursement is not intended to save significant money, nor intended to restore physician incomes to more equitable levels. It is intended to address the oversupply of physicians without confronting either the universities or the foreign trained lobby.

The elite tranche of medical schools do their part to relieve physician oversupply without reducing class size, through the encouragement of their students to go into research. I was well along at the National Institutes of Health before I finally decided I had not gone into medical school with that goal, and returned to teaching and patient care in a more satisfying model not too different from CVIM's obviously Pennsylvania Dutch spirit. The Amish at the far western end of Chester County reject the whole idea of insurance; their most characteristic statement is "Don't send me no bills." That attitude is rather a contrast with the shiny housing and automobiles in the Silicon Valley developments of Southern Chester County, or even with some rather bewildered Quaker farm families scattered over the rest of the county next to the horsey set. Chester County is America.

On Second Street in Society Hill, next to the park where William Penn's house stood and a few feet from Bookbinders, is the house of Dr. Thomas Bond. Bond conceived the idea of building the first hospital in America and with Franklin's publicity machine succeeded in getting it built, to care for the "sick poor". Dr. Bond started a second enduring tradition as well. When the Legislature expressed doubt that the institution was sustainable, he pledged to convince the local medical profession to serve the poor without charge. Some of the legislators who voted for the measure did so in the belief that charity care would never appear so the gesture would be without cost. The physicians did indeed come forward, in sufficient numbers to run many institutions for two hundred years. In 1965 health insurance made its national appearance and has regarded the benchmark low costs of charity care as a threat, ever since.

No Laborer Left Behind

|

| Ivy League |