3 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Colonial Times

More than half of American history took place before 1776, but after 1492. For Philadelphia, Colonial history lasted about a century.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Philadelphia, A Running Commentary

A series of observations in and around Philadelphia by notables over the last three and one-half centuries.

Delaware Bay Before the White Man Came

Captain John Smith of Virginia, sometime friend of Pocahontas, wrote a letter to Captain Henry Hudson that he understood there was a big gap in the continent to the North of the Virginia Capes, and maybe this was the Northwest Passage to China. Hudson set out to look for it.

|

| Hudson |

Smith's misjudgment now seems like a credible story if you take the ferry from Lewes, Delaware to Cape May, New Jersey. You are out of sight of land for half an hour on that trip, and it's a hundred miles of blue salt water to Philadelphia if you decided to go in that direction. In fact, the bay widens out to double the width or more, just inside the capes, and you can see how an explorer in a little sailboat might believe there was clear sailing to the Indies if you went that way. But as a matter of fact, Hudson encountered so much "shoal" that he ran aground repeatedly trying to sail into the bay, and soon gave up. He encountered a swamp, not an ocean passage. The Hudson River, and later Hudson's Bay, seemed like better bets.

What Hudson had encountered was one of the largest gaps in the chain of Atlantic barrier islands, formed by the crumbling of the Allegheny Mountains into the sea, and then washed up as beach islands by the ocean currents. At various points, the low flat sandy islands became re-attached to the mainland as the intervening bay silted up, and that's why the islands of New Jersey and Delaware seem like part of the mainland. And that's what would have happened to the whole Delaware Bay if it hadn't been ditched and dredged, and wave action diverted with jetties. The swamp was a great place to breed insects, so fish were abundant, and that brought birds in vast numbers. Two stories illustrate.

|

| Horseshoe Crabs |

Once a year, a zillion ugly Horseshoe Crabs crawl out of the sea onto the Lewes beaches, and lay a million zillion eggs in the sand. Almost to the moment, a swarm of South American birds swoops out of the skies to eat the eggs. Those birds started flying months earlier from thousands of miles away, but their timing with regard to Delaware crab eggs is perfect, so this evolutionary semi-miracle must have been going on for many centuries.

|

| Cape May |

Now, coming from the other direction, every hour each fall it is possible to see a hawk or two flies south to Cape May, then sort of disappearing in the woods. And then, at some unknown signal, tens of thousands of hawks rise from the bushes and travel together on the thirty-mile passage over the bay and then go on South. Cape May has lots of migratory birds and bird watchers, and it also has Cape May "diamonds", which are funny little stones washed up at the tip of Cape May Point.

In the spring, vast schools of successive species of fish migrate up the Delaware Bay to spawn in the reeds along the shoreline, but as each school encounters the point where the salt water turns fresh, they stop dead. They mill around at this point for several weeks adjusting to the change of water and then go on about their business. While they are there, it is possible for amateurs to catch amazing amounts of fish, if you know the best time, and if you know where the salinity changes. Since heavy or light rainfall can shift the salinity barrier fifty miles, you have to own your own boat if you want to enjoy this phenomenon, since the rental boats are all spoken for months in advance. Fishermen don't like to tell you about such things; patients of mine who literally owed me their lives have refused to say where I might find the fish this year.

Over on the New Jersey side of the bay, oysters like to grow, although something has just about wiped them out in recent decades. There is a town called Bivalve, which is worth a visit just to see the towering piles of oyster shells left over from last century. For miles around, the roads are actually paved with ground-up oyster shells. Up north around Salem, the shad used to run by the millions until the warm water emerging from the Salem (nuclear) power plant attracted them into the intake pipes and action was taken to abate the nuisance. The Salem Country Cub is one of the few places where planked shad can be obtained in season. The system is to split the fish open and nail it to a board, which is then placed in the big open fireplace to cook, and sizzle, and smell just wonderful good. On the other hand, if you want to buy shad in season (March-May) and cook it at home, the place to get it is in Bridgeton.

At the far northern end, at Trenton, the real Delaware River flows into the bay. The area has long since been dredged, but at one time the "falls" at Trenton were notable. Even today, if you travel upriver almost to Lambertville, you will see the river drop over several small ledges. Actually, rapids would probably be a better descriptive term, since Delaware picks up quite a strong current coming down from the Lehigh Valley. In seasons of heavy rainfall, the falls can be completely "drowned".

And down at Philadelphia where we live, the Schuylkill joined Delaware, forming the largest swamp of all at the river junction, a place once famous for its enormous swarms of swans. The Dutch discovered a high point of land at what is now called Gray's Ferry and made it into a trading place for beaver skins from the local Indians. There seems no reason to doubt the report that they took away thirty thousand beaver skins a year from this trading post, now the University of Pennsylvania.

An English sailing vessel was once blown to the East side of Delaware at what would now be Walnut Street in Philadelphia, and it was recorded in the ship's log that it was scraped by overhanging tree limbs. The high ground at that point seemed like a favorable place to situate a city because the water was deep enough for ocean vessels. They had stumbled on one of the relatively few places in the whole bay that was both defensible and navigable, where the game was abundant, and fishing was good. The rest is history.

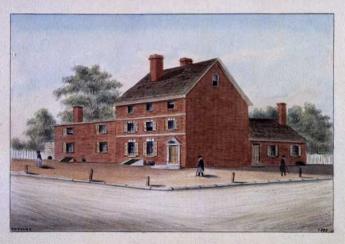

Philadelphia in 1658

|

| Annals of Philadelphia |

Of all the settlers prior to Penn, I feel most interested to notice the name of Jurian Hartsfield, because he took up all of Campington, 350 acres, as early as March 1676, nearly six years before Penn's colony came. He settled under a patent from Governor Andros. What a pioneer, to push on to such a frontier post! But how melancholy to think, that a man, possessing the freehold of what is now cut up into thousands of Northern Liberty lots, should have left no fame, nor any wealth, to any posterity of his name. But the chief pioneer must have been Warner, who, as early as the year 1658, had the hardihood to locate and settle the place, now Warner's Willow Grove, on the north side of the Lancaster Road, two miles from the city bridge. What an isolated existence in the midst of savage beasts and men must such a family have then experienced! What a difference between the relative comforts and household conveniences of that day and this! Yea, what changes did he witness, even in the long interval of a quarter of a century before the arrival of Penn's colony! To such a place let the antiquary now go to contemplate the localities so peculiarly unique!"

--John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time

Germantown Before 1730

|

| Rev. Wilhelm Rittenhausen |

The flood of German immigrants into Philadelphia after 1730 soon made Germantown, into a German town, indeed. From 1683 to 1730, however, Germantown had been settled by Dutch and Swiss Mennonites, attracted by the many similarities between themselves and the Quakers of England. They spoke German dialects to preserve their separateness from the English-speaking majority but belonged to distinctive cultures which were in fact more than a little anti-German. This curiosity becomes easier to understand in the context of the mountainous Swiss burned at the stake by their Bavarian neighbors, Rhinelanders who sheltered them from various warring neighbors, and Dutchmen at the mouth of the Rhine, all adherents of Menno Simon the Dutch Anabaptist, but harboring many differences of viewpoint about the tribes which surrounded them.

Anabaptism is the doctrine that a child is too young to understand religion, and must be re-baptized later when his testimony will be more binding. In retrospect, it seems strange that such a view could provoke such antagonism. These earlier refugees were often townspeople of the artisan and business class, rapidly establishing Germantown as the intellectual capital of Germans throughout America. This eminence was promoted further through the establishment by the Rittenhouse family (Rittinghuysen, Rittenhausen) of the first paper mill in America. Rittenhousetown is a little collection of houses still readily seen on the north side of the Wissahickon Creek, with Wissahickon Avenue nestled behind it. The road which now runs along the Wissahickon is so narrow and windy, and the traffic goes at such dangerous pace, that many people who travel it daily have never paid adequate attention to the Rittenhousetown museum area. It's well worth a visit, although the entrance is hard to find (try going west on Wissahickon Avenue then turning around, a little beyond the entrance).

Even today, printing businesses usually locate near their source of paper to reduce transportation costs. North Carolina is the present pulp paper source, several decades ago it was Michigan. In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, paper came from Germantown, so the printing and publishing industry centered here, too. When Pastorius was describing the new German settlement to prospective immigrants, he said, "Es ist nur Wald" -- it's just a forest. A forest near a source of abundant water. Some of the surly remarks of Benjamin Franklin about German immigrants may have grown out of his competition with Christoper Sower (Saur), the largest printer in America, and located of course in Germantown.

Francis Daniel Pastorius was sort of a local European flack for William Penn. He assembled in the Rhineland town of Krefeld a group of Dutch Quaker investors called the Frankford Company. When the time came for the group to emigrate, however, Pastorius alone actually crossed the ocean; so he was obliged to return the 16,000 acres of Germantown, Roxborough and Chestnut Hill he had been ceded. Another group, half Dutch and half Swiss, came from Krisheim (Cresheim) to a 6000-acre land grant in the high ground between the Schuylkill and the Delaware. The time was 1683. The heavily Swiss origins of these original settlers give an additional flavor to the term "Pennsylvania Dutch".

Where the Wissahickon crosses Germantown Avenue, a group of Rosicrucian hermits created a settlement, one of considerable musical and literary attainment. The leader was John Kelpius, and upon his death the group broke up, many going further west to the cloister at Ephrata. From 1683 to 1730 Germantown was small wooden houses and muddy roads, but there was nevertheless to be found the center of Germanic intellectual and religious ferment. Several protestant denominations have their founding mother church on Germantown Avenue, Sower spread bibles and prayer books up and down the Appalachians, and even the hermits put a defining Germantown stamp on the sects which were to arrive after 1730. The hermits apparently invented the hex signs, which were carried westward by a later, more agrarian, German peasant immigration, passing through on the way to the deep topsoil of Lancaster County.

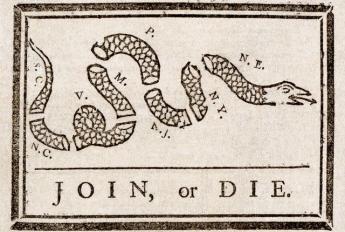

Quakers Turn Their Backs on Power

There have been a number of excellent books about Ben Franklin lately, but all take his side in the dispute with Quakers. These authors relate Franklin struggled with the Quakers, fought with that political party, heroically overcame them with wisdom and guile. Good thing, too, or we all might still be subjects of the British crown.

Well, within the Quaker community these events are viewed differently. Around the year 1755, the Quakers who owned and ran Pennsylvania abruptly turned away from politics and left the government to their political enemies, rather than compromise religious principles. It is difficult to think of any other instance in history when a ruling party decided to become humble subjects of the opposing party, simply because they refused to do what obviously had to be done.

The background of this perplexing issue goes back to the founding of the Quaker colonies, which had lived in a real Utopia for seventy-five years. Repeatedly it had been true that if they just followed the highest principle, things worked out well for everybody. For example, they didn't need to buy the land a second time from the Indians, but they did, with the gratifying result of peaceful co-existence while other colonies experienced constant Indian wars. Penn negotiated the borders of his states with the neighbors, and although it took decades, brought peace and prosperous trade in return. Strict honesty in mercantile matters led to a reputation for trustworthiness, and that in turn led to prosperous commerce. Using a fixed price rather than haggling over price speeded up transactions, gained respect for fair dealing, led to more prosperity. Just you do the right thing, and all will be well. That includes extending freedom of religion, welcoming strangers to the colony to worship together in peace.

Toward the end of this Utopian period, some questions began to arise. More and more non-Quakers came to the colony, making the colony progressively less Quaker. That was a silent disappointment to William Penn. The founder had been a charismatic evangelist for his religion as a youth but came to grave disappointment about peaceful persuasion by the end of his life. Convincing the adherents of other religions of reasonable Quaker principles had often proved to be as intractably difficult as arguing religion with Henry VIII. The Quakers, a religion without a clergy, were appalled that so many adherents of other religions did not concern themselves with earnest reasoning, preferring to do strictly what their ministers told them to do.

Another disconcerting thought was growing within the Quaker community that success itself might be corrupting them. Worldliness seemed to grow inevitably out of wealth and prominence; all power does tend to corrupt. If you are rich, people always seem to steal from you, and that leads to violent punishments, something regrettable in itself. These were not new arguments, but by 1750 nearly a century of success in paradise had begun to stir Pennsylvania Quakers to wonder why more of their neighbors did not ask to become Members. These were troubling concerns of the day which would probably have worked themselves out, except that far-away France and England declared war on each other. The French responded by stirring up the Indians along the Western frontier. Pennsylvania settlers were soon scalped, kidnapped and burned at the stake. Something had to be done about it since protection was a duty of government, and effective protection now had to be non-peaceful. The Quakers dithered. More Scotch-Irish settlers around Pittsburgh were slaughtered. The Quaker meetings sent minutes to the Quakers in the legislature that they must not compromise their peaceful principles, and the Scotch-Irish exploded with rage. The Meetings told their representatives to resign from office, their members to retreat from politics altogether.

So Ben Franklin rose to the occasion, and General Forbes led an army to Fort Duquesne at the forks of Ohio, and Colonel George Washington was the hero of that day. The French were driven off the frontier, the English were victorious at Quebec. North America became a British continent.

Meanwhile, the Quakers retreated into tight-lipped solitude. And self-doubt, because the episode seemed to demonstrate that rigidly peaceful principles cannot govern a state or a nation if that nation contains others unwilling to be sacrificed for peaceful principles. An unthinkable logic emerged; freedom of religion led to conflict with the duty of a non-violent government to protect its citizens. It began to be clear it was the duty of government to enforce its laws, by force if necessary. Underneath the pile of documents, was a gun.

So, the Quakers proudly walked away from power and dominance, for all time. Sadly, too, because the significance was clear. Peaceful utopia may be not possible, within a dangerous world.

America in 1767

|

| Johann de Kalb |

Baron Johann de Kalb was to die a hero of the American Revolution in 1780, but in 1767 he was a spy for France, scouting out potential French opportunities in America. He made the following report to the French minister of foreign affairs, duc de Choiseul:

"Everywhere there are children swarming like broods of ducks, large fertile farms, flourishing industries, and harborsbarely able to hold the and fishing and Merchant Fleets

"Whatever may be done in London," judged de Kalb, "this country is growing too powerful to be much longer governed at such a distance."

- as cited by Walter A. MacDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner

REFERENCES

| Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History: 1585-1828: Walter A. McDougall ISBN-13: 978-0060197896 | Amazon |

Philadelphia in October, 1774

|

| Vice President John Adams |

In his diary, John Adams tells of leaving Philadelphia at the conclusion of the First Continental Congress: "28.Friday. Took our departure, in a very great rain, from the happy, the peaceful, the elegant, the hospitable, and polite city of Philadelphia. It is not very likely that I shall ever see this part of the world again, but I shall ever retain a most grateful, pleasing sense of the many civilities I have received in it and shall think myself happy to have an opportunity of returning them. Dined at Anderson's and reached Priestly's of Bristol, at night, twenty miles from Philadelphia, where we are as happy as we can wish."

Philadelphia in '76

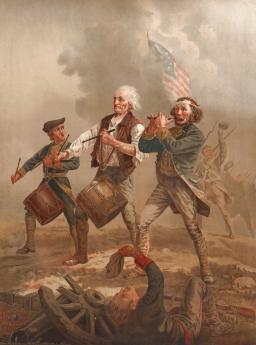

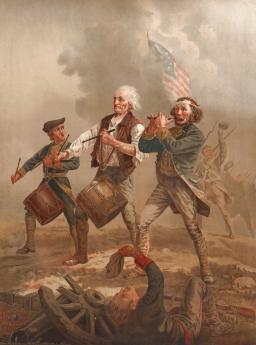

|

| Spirit of '76 |

Although the origins of the American Revolution are subtle and complex, even historically controversial, we have more or less united in the idea that we "declared" our independence from Britain on July 4, 1776. We then spent eight years convincing the British we were serious and have been independent ever since. Reflect, however, on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add to that the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had quite a nerve implying the whole thing was his idea. What's more, New England subsequently had to live with a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging the others along with it. It was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine.

New England was in the position of having started hostilities, and about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What the New Englanders wanted was WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing the dependency on the British homeland, without any sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. Perhaps it was unfortunate that New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming, and without support, New England was likely to be subdued like Carthage.

And then, the last hope for flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, stepped off the boat. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He finally was saying what others had been thinking. It was now, or never.

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

|

| Spirit of 76' |

The American colonies were growing too big, too fast, and the British Empire had too many international distractions, to have smooth relationships across three thousand miles of ocean, using uncertain communications available in the late Eighteenth century. Friction and misunderstanding were inevitable without far more statesmanship than either side thought was necessary. So, when the Continental Congress dispatched George Washington to Boston with troops to defend rebellious Massachusetts at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it was hard for the British to believe the colonists were merely helping out one of their distressed neighbors. It seemed in London that the thirteen colonies had united, formed not only an army but a government, and gone to war. In December 1775 England passed the Prohibitory Act, essentially declaring war, and organized a huge invasion fleet to put down the rebellion. It now seems hard to understand the first notice the Americans had of this huge over-reaction was a private letter to Robert Morris from one of his agents in March 1776; no warnings, no negotiations, no attempt to investigate problems and correct them. The British just sent a fleet to settle this problem, whatever it was. It's all very well to say the Americans should have known they were playing with fire. They didn't see it that way; they were being self-reliant, responding to attack. In June 1776 British patrol frigates were skirmishing in the Delaware River; late in the month, British troops landed on Staten Island. The American reaction to all this was a muddle of confusion. A few were delighted, most of the rest were amazed or appalled.

Although the deeper strategic origins of the American Revolution are subtle, complex, and controversial, there is far less muddle about what happened on July 2, 1776, publicly proclaimed two days later. Adopting a resolution written by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, the Thirteen Colonies stated they had now clarified their goals in the controversy with the British monarchy. For a year before that, the Continental Congress had been corresponding with each other and meeting in Carpenters Hall with the goal of achieving representation in the British parliament -- "No taxation without representation". The model for most of them was based on the Whig agitation for Ireland -- for a local parliament within a larger commonwealth. But the passing of the British Navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then the actual appearance of seven hundred British warships in American waters showed that not only was Parliamentary representation out of the question, but King George III was going to play rough with upstarts. The new goal was no longer just representation, it was independence. If we were going to resist a military occupation at the risk of being hanged as traitors, we might as well do it for something substantial. The meeting had a number of Scotch-Irish Princeton graduates, whose basic loyalty to England had long been divided. Pacifist Pennsylvania, chief among the wavering hold-outs, was mostly won over by its own Benjamin Franklin, who was optimistic the French would help us. Even so, both Robert Morris and John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration; Franklin persuaded both to abstain by absence, which created a majority of the Pennsylvania delegation in favor. That's a pretty slim majority for a crucial decision. Franklin was soon dispatched back to Paris to make an alliance; Washington was dispatched to hold off that British army in the meantime. Jefferson was designated to write a proclamation, which even after editing is still pretty unreadable beyond the first couple of sentences. Meeting adjourned. This brief account may not qualify as a serious examination of the causes of the American Revolution, but it comes close to the way it seemed to the colonist in the street.

|

| Colonist's Complaint |

The rebels then spent eight years convincing the British they were serious and have been independent ever since. But, just a minute, here. Reflect on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers even waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had a big nerve implying the whole Revolution was his idea. What's more, there's a viewpoint that New England subsequently had to endure a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation because loud talk from New England still made the rest of the country nervous. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging others along with it. Rather, it was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine. When Independence was finally declared the goal, many of Philadelphia's leading citizens moved to Canada.

New England had started hostilities and was about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What New England and the Scotch-Irish needed were WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. Virginia was incensed about its powerlessness against British mercantilism, especially the tobacco trade. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing dependency on the British homeland, without a sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. It was perhaps unfortunate New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a military confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming. Without support, New England was likely to be torched, as Rome once subdued Carthage.

And the last hope for an alternative of flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, had stepped off the boat a year earlier. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, arrived with the news he had finally had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He was a man who quietly made things happen, carefully selecting his arguments from amongst many he had in mind. In retrospect, we can see that he held the idea of Anglo-Saxon world domination as far back as the Albany Conference of 1745, and could even look forward to America outgrowing England in the 19th Century. His behavior at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 strongly suggests he never completely gave up that long-term dream. Just as Edmund Burke never gave up the idea of Reconciliation with the Colonies, Benjamin Franklin never quite gave up the idea of Reconciliation with England. While John Dickinson and Robert Morris resisted the idea of Independence down to the last moment, Franklin took a much longer view. For the time being, it was necessary to defeat the British, and for that, we needed the help of the French. In 1750, America joined with the British to toss out the French. And then in 1776, we joined the French to toss out the British. Franklin didn't always get his way. But Franklin was always steering the ship.

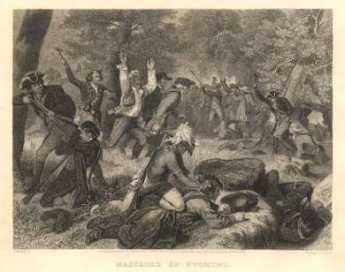

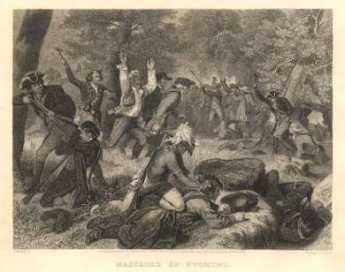

The Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778

|

| The Wyoming Massacre |

The six nations of Iroquois dominated Northeastern America by the same means the Incas dominated Peru -- commanding the headwaters of several rivers, the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Susquehanna, as well as the long finger lakes of New York, leading like rivers toward Lakes Ontario and Erie. They were thus able to strike quickly by canoe over a large territory. Iroquois were quite loyal to the British because of the efforts of Sir William Johnson, who settled among them and helped them advance to quite a sophisticated civilization. It even seems likely that another fifty years of peace would have brought them to an approximately western level of culture. Aside from Johnson, who was treated as almost a God, their leader was a Dartmouth graduate named Brant.

Brant, The Noble Savage

The mixed nature of the Iroquois is illustrated by the fact, on the one hand, that Sachem Brant translated the Bible into Mohawk and traveled in England raising money for his church. On the other hand, his biographers trouble to praise him for never killing women and children with his own hands. British loyalty to these fierce but promising pupils was one of the main reasons for the 1768 proclamation forbidding colonist settlement to the West of what we now call the Appalachian Trail, which on the other hand was itself one of the main grievances of the rebellious land-speculating colonists. The Indians, for their part, saw the proclamation line as their last hope for survival. After Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, the Indian allies were free to, and probably urged to, attack Wyoming Valley.

It is now politically incorrect to dwell on Indian massacres, but this one was both exceptionally savage, and very close to home. The Iroquois set about systematically exterminating the rather large Connecticut sub-colony and came pretty close to doing so. Children were thrown into bonfires, women were systematically scalped and butchered. The common soldiers who survived were forced to lie on a flat rock while Queen Esther, "a squaw of political prominence, passed around the circle singing a war-song and dashing out their brains." That was for common soldiers. The officers were singled out and shot in the thigh bone so they would be available to be tortured to death after the battle. The Wyoming Massacre was a hideous event, by any standard, and it went on for days afterward, as fugitives were hunted down and outlying settlements burned to the ground.

It's pretty hard to defend a massacre of this degree of savagery, but the Indians did have a point. They quite rightly saw that white settler penetration of the Proclamation Line would inevitably lead to more penetration, and eventually to the total loss of their homeland. The defeat of a whole British Army under Burgoyne showed them that they were all alone. It was do or die, now or never. Countless other civilizations have been extinguished by provoking a remorseless revenge in preference to a meek surrender.

Franklin's Funeral, 1790

|

| Benjamin Franklin's Grave |

"Philadelphia's silver decade began with the death of Benjamin Franklin, at the age of eighty-four, in 1790. On April 21, some 20,000 people, nearly half the city, lined the route of Franklin's funeral procession from the State House to the Christ Church burying ground. The procession was led by the clergy of the city, and the coffin was carried by six pallbearers:General Thomas Mifflin<, president of Pennsylvania; Thomas McKean, chief justice; Samuel Powell, mayor of Philadelphia; Thomas Willing, president of the Bank of North America; David Rittenhouse, professor of astronomy at the College of Philadelphia; and William Bingham, the richest man in America, member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, and soon to be appointed United States senator from the state. There followed the family and close friends, members of the state Assembly, judges of the State Supreme Court, gentlemen of the bar, printers with their journeymen and apprentices, and members of the Philosophical Society and a host of other associations that Franklin had founded. Doctor Rush sent a lock of Franklin's hair to the Marquis de Lafayette, and when the news reached France, the National Assembly heard a eulogy on the "sage of two worlds" by Mirabeau and sent a letter of sympathy to its sister Republic."

--E. Digby Baltzell, Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia

Those who have experience with arranging state funerals will notice the strong Pennsylvania character of the funeral, and the subdued prominence of national figures, especially those from Virginia, Massachusetts, and New York. Some historians have noticed this anomaly, even surmising that Washington and others were jealous of Franklin's fame. However, the Capital was in New York City until August 12, 1790, and did not move to Philadelphia until December 6, 1790. Under the circumstances, it might have been difficult even to be certain the news of his death on April 17 had reached all the national leaders by April 21, let alone orchestrate arrangements of the funeral ceremonies around their uncertain presence at it.

Furthermore, he had a long life, from rags to riches, through three wars, after many publications, organizations, discoveries and honors, and some heavy tribulations. But those who have themselves lived 84 years will recognize that it all passes rapidly, and seems like a short dream to the central figure.

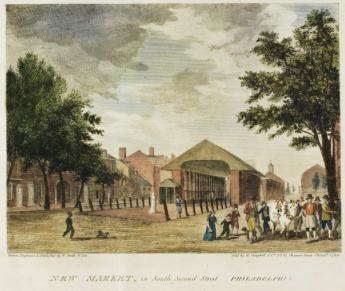

Philadelphia in 1800

|

| Philadelphia 1800 |

IN the year 1800 Philadelphia, with a population of 70,000, was the first city in America: New York was growing rapidly (its population rose from 33,000 to 60,000 between 1790 and 1800); Boston, however, was a more or less static provincial town of 25,000. Philadelphia was not only the temporary capital of the new nation but also its publishing, artistic, literary, and social center. As Henry Adams put it, Boston was our Bristol, New York our Liverpool, and Philadelphia our London."

--E. Digby Baltzell, Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia

Philadelphia: Charles Dickens Gives an 1842 Viewpoint

|

| Charles Dickens |

In 1842, Charles Dickens wrote a short summary of Philadelphia for the readers back home in London-

My stay in Philadelphia was very short, but what I saw of its society, I greatly liked. Treating of its general characteristics, I should be disposed to say that it is more provincial than Boston or New York and that there is a float in the fair city, an assumption of taste and criticism, savoring rather of those genteel discussions upon the same themes, in connection with Shakespeare and the Musical Glasses, of which we read in the Vicar of Wakefield.

Mark Twain Sees Philadelphia in 1853

|

| Mark Twain |

In 1853 Mark Twain, then a 17 year-old vagabond, made his first visit to Philadelphia. To support himself, he worked several months for the Philadelphia Inquirer as a typesetter, a fact that makes the present newspaper very proud. His comments (which differ strikingly from the sour views of his later Connecticut Yankee days) follow:

"The old State House in Chestnut Street, is an object of great interest to the stranger; and though it has often been repaired, the old model and appearance are still preserved. It is a substantial brick edifice, and its original cost was L5,600 ($28,000). In the east room of the first story the mighty Declaration of Independence was passed by Congress, July 4th, 1776.

|

| Philadelphia's Independence Hall |

"When a stranger enters this room for the first time, an unaccountable feeling of awe and reverence comes over him, and every memento of the past his eye rests upon whispers that he is treading upon sacred ground. Yes, everything in that old hall reminds him that he stands where mighty men have stood; he gazes around him, almost expecting to see a Franklin or an Adams rise before him. In this room is to be seen the old "Independence Bell", which called the people together to hear the Declaration read, and also a rude bench, on which Washington, Franklin, and Bishop White

"It is hard to get tired of Philadelphia , for amusements are not scarce. We have what is called a 'free-and-easy,' at the saloons on Saturday nights. At a free and easy, a chairman is appointed, who calls on any of the assembled company for a song or a recitation, and as there are plenty of singers and spouters, one may laugh himself to fits at a very small expense. Ole Bull, Jullien and Sontag have flourished and gone, and left the two fat women, one weighing 764, and the other 769 pounds, to "astonish the natives." I stepped in to see one of these the other evening and was disappointed. She is a pretty extensive piece of meat, but not much to brag about; however, I suppose she would bring a fair price in the Cannibal Islands. She is a married woman! If I were her husband, I think I could yield with becoming fortitude to the dispensations of Providence, if He, in his infinite goodness, should see fit to take her away! With this human being of the elephant species, there is also a "Swiss Warbler"--Bah! I earnestly hope he may live to see his native land for the first time."

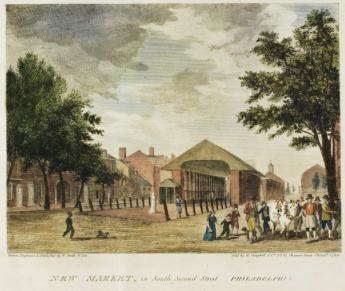

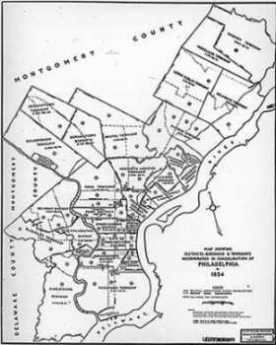

Philadelphia City-County Consolidation of 1854

|

| Consolidation Map 1854 |

Philadelphia is still referred to as a city of neighborhoods. Prior to 1854, most of those neighborhoods were towns, boroughs, and townships, until the Act of City-County Consolidation merged them all into a countywide city. It was a time of tumultuous growth, with the city population growing from 120,000 to over 500,000 between the 1850 and 1860 census. There can be little doubt that disorderly growth was disruptive for both local loyalties and the ability of the small jurisdictions to cope with their problems, making consolidation politically much more achievable. A century later, there were still two hundred farms left in the county which was otherwise completely urbanized and industrialized. For seventy-five years, Philadelphia had the only major urban Republican political machine. By 1900 (and by using some carefully chosen definitions) it was possible to claim that Philadelphia was the richest city in the world, although this dizzy growth came to an abrupt end with the 1929 stock market crash, and the population of Philadelphia now shrinks every year. In answering the question of whether consolidation with the suburbs was a good thing or a bad thing, it was clearly a good thing. But since Philadelphia is suffering from decline, it becomes legitimate to ask whether its political boundaries might now be too large.

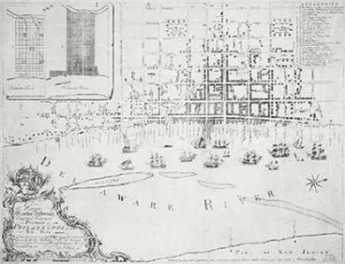

|

| Philadelphia Map 1762 |

The possible legitimacy of this suggestion is easily demonstrated by a train trip from New York to Washington. The borders of the city on both the north and the south are quickly noticed out the train window, as the place where prosperity ends and slums abruptly begin. In 1854 it was just the other way around, just as is still the case in many European cities like Paris and Madrid. But as the train gets closer to the station in the center of the city, it can also be noticed that the slums of the decaying city do not spread out from a rotten core. Center City reappears as a shining city on a hill, surrounded by a wide band of decay. The dynamic thrusting city once grew out to its political border, and then when population shrank, left a wide ring of abandonment. It had outgrown its blood supply. Prohibitively high gasoline taxes in Europe inhibit the American phenomenon of commuter suburbs. The economic advantage of cheap land overcomes the cost of building high-rise apartments upward, but there is some level of gasoline taxation which overcomes that advantage. Without meaning to impute duplicitous motives to anyone, it really is another legitimate question whether some current "green" environmental concerns might have some urban-suburban real estate competition mixed with concern about global warming. Let's skip hurriedly past that inflammatory observation, however, because the thought before us is not whether to manipulate gas taxes, but whether it might be useful to help post-industrial cities by contracting their political borders.

Before reaching that conclusion, however, it seems worthwhile to clarify the post-industrial concept. America certainly does have a rust belt of dying cities once centered on "heavy" industry which has now largely migrated abroad to underdeveloped nations. But while it is true that our national balance of trade shows weakness trying to export as much as we import, it is not true at all that we manufacture less than we once did. Rather, manufacturing productivity has increased so substantially that we actually manufacture more goods, but we do it with less manpower and less pollution, too. The productivity revolution is even more advanced in agriculture, which once was the main activity of everyone, but now employs less than 2% of the working population. This is not a quibble or a digression; it is mentioned in order to forestall any idea that cities would resume outward physical growth if only we could manipulate tariffs or monetary exchange rates or elect more protectionist politicians to Congress. Projecting demographics and economics into the far future, the physical diameters of most American cities are unlikely to widen, more likely to shrink. If other cities repeat the Philadelphia pattern, the vacant land for easy exploitation lies in the ruined band of property within the present political boundaries of cities, or if you please, between the prosperous urban center and the prosperous suburban ring.

Many American cities with populations of about 500,000 do need more room to grow, so let them do it just as Philadelphia did a century ago, by annexing suburbs. But there are other cities which have lost at least 500,000 population and thus have available low-cost low-tax land which would mostly enhance the neighborhood if existing structures were leveled to the ground. Curiously, both the shrunken urban core and the bumptious thriving suburbs could compete better for redeveloping this urban desert if the obstacles, mostly political and emotional, of the political boundary, could be more easily modified. But that's also just a political problem, and not necessarily an unsolvable one.

Philadelphia in 1876: The Centennial

|

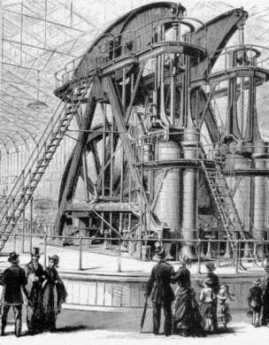

| The Centennial Exhibition |

The Centennial Exhibition could easily claim to be the most transforming event that ever happened to our town. It represented the hundredth year of our independence, although 1887 would be the hundredth anniversary of our nation, and anyway, the Declaration of Independence was just sort of a hook to hang the exhibition on. Opened in the spring with a speech by the Civil War victor, Ulysses S. Grant, it was also closed in the fall with another speech by him. The planning, design, and atmosphere of the whole thing was triumphalism -- the world will never be the same because this country has arrived. The exhibition introduced to an awe-struck world, the electric light bulb, the typewriter, and the telephone. We've won the Civil War, and this is how we won it. It's too bad of course that we had to tousle up the South that way, but look at how great it is going to be to participate in the Colossus of Tomorrow.

|

| Corliss Steam Engine. |

The civilized world competed with each other to display their things of pride in national pavilions. And next to them was even bigger pavilions by the States, with even more matters of pride to display. The main exhibition hall covered twenty-one acres. The future was here, and it was machinery. Machinery Hall was filled with thousands of machines of one sort or another, and wonder of wonders, they were all driven by one operator controlling a single huge engine, the Corliss Steam Engine. The Age of Artisans and Craftsmen was over. We had entered the world of Industrialism.

It was intended that the rest of the world should take notice of America, and of course of America's bumper City. Less noticed was that Philadelphia woke up to the rest of the world. Over eight million people attended the exhibition, most of them Americans. A great many Philadelphians spent a whole week poring over the exhibits, and some even spent a whole month doing it. Just as Japan got the jolt of its life when Commodore Peary showed them just how far-out-of-it-all they were, Philadelphia got the same jolt from the European exhibitors at the Centennial. We were showing off, but we were learning.

The Definition of a Real Philadelphian (1914)

|

| Elizabeth Robbins Pennell |

There are several million people living in Philadelphia, but of course, not all of them are real Philadelphians. >Elizabeth Robbins Pennell, a friend and biographer of James McNeill Whistler, tells us the definition of a real Philadelphian in 1914.

"I think I have a right to call myself a Philadelphian, though I am not sure if Philadelphia is of the same opinion. I was born in Philadelphia, as my father was before me, but my ancestors, having had the sense to emigrate to America in time to make me as American as an American can be, were then so inconsiderate as to waste a couple of centuries in Virginia and Maryland, and my Grandfather was the first of the family to settle in a town where it is important, if you belong at all, to have belonged from the beginning. However, [my husband's] ancestors, with greater wisdom, became at the earliest available moment not only Philadelphians, but Philadelphia Friends, and how much more that means Philadelphians know without my telling them. And so, as he does belong from the beginning, and as I would have belonged had I had my choice, for I would rather be a Philadelphian than any other sort of American, I do not see why I cannot call myself one despite the blunder of my forefathers in so long calling themselves something else."

--Our Philadelphia, 1914

Philadelphia: A 1925 Viewpoint

|

| Philadelphia Trolley |

In 1925, George Barton published a charming series of reflections about his own wanderings around downtown Philadelphia, entitled "Little Journeys Around Old Philadelphia".

Christmas Reflections

My father in law, a prominent obstetrician in Binghamton, New York, regularly took his family to New York City sometime between Thanksgiving and Christmas. The three-day junket was described as a visit to do Christmas shopping. Another relative made similar trips from home in Tyler, Texas. Several of my patients made such visits to Philadelphia from their homes in West Virginia, stopping by to make a medical visit to me during the same trip. From the seasonal crowds in Penn Station and in the shops on Chestnut Street, it was clear that an annual visit to the big city was a common custom in the upper crust of small to medium-sized cities, for whom the more expensive shops of the bigger city provided big-ticket items bought infrequently, and the distinctive luxuries which made them stand out from the socially less-enlightened back home.

These shopping visits were not confined to purchasing, although that was the main focus. It was a time to go to the theater, orchestra and opera, maybe an occasional ballet and art exhibit. The choice of a large city might be related to returning to the University, or another period of professional training for a drop-in visit because these associations made it possible to observe the latest trends and innovations, a useful issue in the smaller towns. The ladies could observe the trends in fashions, and everyone would have a chance to dress up in the better hotels and restaurants. This recirculation between the small towns and the big one at the hub unified the region, establishing hierarchy rather widely. And it hardened traditions in the big city, since islanders tend to return to the same hotel, restaurants and social gathering spots even more than the local residents do; there isn't time in a brief visit to shop for new venues, unless the trip itself reveals that times and places have somehow changed in an important way.

|

| Wannamakers Pipe Organ |

That's all changed, today. The pipe organ at Wannamakers, the cluster of department stores around Eighth and Market, the theater district, Caldwell's and Bailey Banks and Biddle upscale jewelers, the fancy women's clothing shops on Walnut and Chestnut Streets, and the bespoke men's tailor shops -- have disappeared in a slew of retail despond. The excited crowds of upscale shoppers have dwindled, at least in the center city shopping area. Students of sociology point to the decline of the department store as a central commotion in the center of this phenomenon, blaming that in turn on the spread of national brand names by television and more electronic forms of advertising. The department store did your comparison shopping for you, putting its brand name on the product and placing its reputation behind the choice. If Wannamaker could determine that a Japanese radio was of high quality, it became Wanamaker's radio. Today, Samsung and Sony do their own advertising, sell their products through outlets in the suburban malls. Philadelphia residents enjoy as much retail choice and pricing as ever, they just shop in the malls located along the Interstate circumferential highway, just outside what used to be the outermost suburbs. So the volume of retail shopping among Philadelphians probably hasn't changed a great deal; it has merely shifted to the malls where there is parking for your car to transport goods which the department stores used to deliver. It is the annual visits from the subordinate small cities at moderate distance that has disappeared. Small cities now have their own shopping malls, carrying national brand name merchandise. Losing this source of business, the associated entertainment industry has declined to a point below sustainability for most of them -- in the center city hub. Along with the disappearance of this regional recirculation, small cities have lost their sense of affiliation with a bigger one. The small-town professional class which was the biggest participant in this annual migration is professionally more isolated but so are their clients. The upper crust of the small town now must constrain its horizon to the smaller town professionals, with their lesser claim to distinction. For a while, the disparity can be overcome by specialization, but ultimately the distinction of the big-city specialist rests on assembling a richer experience from wider drawing power. In Medicine at least, the insistence of Medicare on paying the same fee for the same service lessens the economic incentive for self-repair of the system.

|

| Wannamaker's Christmas Light Show |

Meanwhile, nature of Christmas itself is becoming standardized. Fewer people make their own Christmas presents, whether through knitting or baking. If the process of commercial gifts goes the full distance, eventually the joy of searching for exactly the right gift will seem more like paying your taxes. These things already cost too much, are worth too little, and neither the process of giving a gift nor the process of receiving a welcome gift will retain much joy. Or significance. What was until recently a Christian religious celebration has become diversified into a generic "Happy Holiday", presumably in order to avoid offense to other religious groups who themselves likely persist in their old traditions of ritual greeting. The assault on Christmas is however not primarily cultural, but commercial. The silent ostentation of elaborate outdoor lighting and the secular versions of Christmas carols endlessly replayed over loudspeakers in stores, probably have a more destructive effect on the community winter solstice ceremony than any competition for religious adherence.

The coming next step in the modification of the Christmas season is dimly visible in the assault of pocket telephones on the suburban shopping mall. After enjoying only a few years of victory over the center city department store, malls must now confront shoppers with portable telephones containing a camera and GPS geographical locator. Seeing something he likes, the shopper of the future can photograph its bar code in the shop display, and be immediately told of all the neighboring stores which sell the same product for a lower price. Electronics are thus about to turn Christmas shopping into an electronic auction, no doubt making it eventually easier to do the shopping from home.

What Christmastime means to me is a recollection of what it once was like at the nation's oldest hospital, and not so terribly long ago, at that. Before 1965, the Pennsylvania hospital had been staffed for centuries with unpaid student nurses, working under the direction of unpaid doctors in training, supervised by volunteer attending physicians. Of the five hundred beds, only forty were filled with paying patients and the rest were housed in long communal halls. On Christmas morning at 7 AM, the drowsy patients were astonished to be awakened by a procession of very pretty student nurses, led by Miss McClellan the grim-looking Directress of nursing, and followed by a handful of internet and residents, all singing Christmas carols and carrying lighted candles in the dark. Miss McClellan herself was never heard to utter a note, but the student nurses had been trained in four-part harmony, and the interne doctors were enthusiastic followers. The faces of the poor old indigents in the beds were filled with pure delight as we traipsed past, chanting of the travels of Orient kings, the pregnancy of virgins, and other miracles of the occasion.

Christmas Reflections (Podcast)

Fort Wilson: Philadelphia 1779

|

| James Wilson |

OCTOBER 4, 1779. The British had conquered then abandoned Philadelphia; an order was still only partially restored. Joseph Reed was President of the Continental Congress, inflation ("Not worth a Continental") was rampant, and food shortages were at near-famine levels because of self-defeating price controls. In a world turned upside down, Charles Willson Peale the painter was a leader of a radical group of admirers of Rousseau the French anarchist, called the Constitutionalist Party, leaning in the bloody direction actually followed by the French Revolution in 1789. Peale was quick to admit he had no clue what to do with his leadership position and soon resigned it in favor of painting portraits of the wealthy. Others had deserted the occupied city, and many had not yet returned. The Quakers of the city hunkered down, more or less adhering to earlier instruction from the London Yearly Meeting to stay away from any politics involving war taxes. About two hundred militia roamed the city streets making trouble for anyone they could plausibly blame for the breakdown of civil order. Philadelphia was as close to anarchy as it would ever become; the focus of anger was against the pacifist Quakers, the rich merchants, and James Wilson the lawyer.

|

| Fort Wilson |

Wilson had enraged the radicals by defending Tories in court, much as John Adams got in trouble for defending British troops involved in the Boston Massacre; Ben Franklin advised Wilson to leave town. It is still possible to walk the full extent of the battle of Fort Wilson in a few minutes, and the tourist bureau has marked it out. Begin with the Quaker Meeting at Fourth and Arch. A few wandering militiamen caught Jonathan Drinker, Thomas Story, Buckridge Sims, and Matthew Johns emerging from the Quaker church, and rounded them up as prisoners. The Quakers were marched down the street for uncertain purposes when the militia encountered a group of prominent merchants emerging from the City Tavern. Unlike the meek Quakers, Robert Morris and John Cadwalader the leader of the City Troop ordered the militia to release the prisoners, behave themselves, and disperse; Timothy Matlack shouted orders. It was exactly the wrong stance to take, and about thirty prominent citizens were soon driven to retreat to the large brick house of James Wilson, at the corner of Third and Walnut, known forever afterward as Fort Wilson. Doors were barred, windows manned, and Fort Wilson was soon surrounded by an armed, shouting, mob. Lieutenant Robert Campbell leaned out a third story window and was soon dropped dead by a lucky bullet. It remains in dispute whether or not he fired first. Crowbars were sought, the back door forced open, but the angry attackers scattered after fusillades from inside.

|

| Joseph Reed |

Down the street came President Reed on horseback, ordering the militia to disperse, with Timothy Matlack at his side; both men were well-known radicals, here switching sides to maintain law and order. The City Troop arrived, an order was given the cavalry to Assault Every Armed Man. The radicals were finally dispersed by this makeshift cavalry charge, cutting and slashing its way through the dazed militia. When it was over, five defenders were dead and about twenty wounded. Among the militia, the casualties were heavier but inaccurately reported. Robert Morris took James Wilson in hand and retreated to his mansion at Lemon Hill; Wilson was the founder of America's first law school. Among other defenders huddled in Fort Wilson were some of the future framers of the Constitution from Pennsylvania: General Thomas Mifflin, Wilson, Morris, George Clymer. Equally important was the deep impression left on radical leaders like Reed and Matlack, and Henry Laurens, who could see how close the whole war effort was to dissolution, for lack of firm control. Inflation continued but the center-productive price control system was abandoned and never revived; the Patriots had a bad scare, and the heedless radicals forced to confront the potentially disastrous consequences of their own amateur performance when entrusted with the power and responsibility they had just been demanding. It was one of those rare moments in a nation's history when the way suddenly opens to previously unthinkable actions.

|

| Timothy Matlack |

The Battle of Fort Wilson was the only Revolutionary War battle fought within Philadelphia city limits; a revolution within a revolution, every participant was a Rebel patriot. Reed and Matlack were the two most visibly appalled by the whole uproar, forced by circumstances to attack the forces of their own political persuasion. But it seems very certain that Robert Morris and the other prosperous idealists were also left with an indelible conviction that even a confederation must maintain central command and discipline with an iron will, or all might be lost. A knowledgable French observer estimated that Robert Morris then owned assets worth eight million dollars, an almost unimaginable sum for the time. But he would lose every penny if effective political control could not be restored. A few days later in the October election, he and all the other Republican (conservative) officials lost their seats. It did not matter; Morris then knew what to do, and his opposition didn't.

Quakers and Idolatry

|

| Philadelphia's Quaker Meetinghouse |

There are about forty thousand bodies buried in Philadelphia's Quaker Meetinghouse grounds at Fourth and Arch Streets, which contain only two tombstones. The yellow fever epidemics of the era account for much of that, but it's nevertheless a striking portrayal of early Quaker aversion to anything resembling idolatry. It underlines this attitude by sharp contrast with more recent uproars about desecrating statues of Confederate generals in public spaces of the Old South, which even Robert E. Lee objected to constructing. They led plausibly to erecting and then defacing Union generals in Northern states as well; since it seemed natural for statue-desecration to evolve into an equal-opportunity demonstrations. A little primitive perhaps, but even-handed.

|

| The Fourth Crusade |

Worshiping graven images has a long history. You needn't be a public-statue expert to remember the terracotta Chinese soldiers are two thousand years old, and the Egyptian pyramids are even older. The chariot horses over the Brandenburg Gate make a stronger illustration of the idea, intertwined over the shorter length of Western civilization. Although carvings might be older, we also have a reasonably accurate history of the bronze statues of these horses. The technique evolved with different proportions of copper and tin, with other metals sometimes added, but the underlying idea is to make a hollow bronze statue, giving the appearance of a much heavier solid bronze one, apparently originating in the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey in the second Century. There were in fact two such statues, with different subsequent histories. The Fourth Crusade was the one where Western European Christian Crusaders invaded Constantinople the main eastern Christian capital, never getting to the Holy Land. Even if they started with good intentions, Christians were content to carry off Christian booty, including the bronze horses. One set was sent to Venice and the other set got to the Christians in Southern France.

|

| Frederick the Great |

Frederick the Great put one set in the center of Berlin. In time, Napoleon took both statues to Paris, but later returned them. The one in Berlin, or perhaps copies of it eventually came to symbolize Nazi Germany, but later Checkpoint Charlie. The details of these conquests and adventures are not not of much consequence today, leaving only the central point that someone conquered someone else, and God must love the victor. The main point became victory, dogmas have been forgotten. Only the Quakers seem to be willing to mention another main point: Thousands of people died for these statues, but very few tourists could now tell you why. The Quakers reached a conclusion we might reconsider. Pulverize all statues and churches, thus saving the world from future grief. Since the Quakers also were first to free the slaves but later mostly disapproved of the Civil War, the irony was not lost on them. But most of their grandchildren reversed the assessment. It's too early to say how another generation will be persuaded to feel.

|

| General Lucius Clay |

During the War against Nazi Germany, my uncle was General Lucius Clay's room-mate, and the two of them were appointed to oversee de-Nazification of the defeated Germans by a third Pennsylvania Dutchman, Dwight Eisenhower. The concept was devised by Henry Morgenthau, then Secretary of the Treasury, in a famous letter urging a program to make Germany into an agricultural nation "for a thousand years". Accordingly, my father's brother oversaw the public burning of tons of postage stamps containing swastikas, plus every photograph of Adolph Hitler the Army could locate, along with similar symbols of the Third Reich. Nearly eighty years have passed since then -- essentially two generations, but it still remains illegal to possess such documents. Evidently, a sense of vengefulness so regularly outlasts its provocation, that passing the grievance on to children is usually hard to justify.

| Posted by: Risky | Jun 3, 2012 11:54 PM |

21 Blogs

Delaware Bay Before the White Man Came

This was the last major place on the East Coast to be settled because it was a swampy snaggy pond, full of fish and birds. And soon, pirates.

This was the last major place on the East Coast to be settled because it was a swampy snaggy pond, full of fish and birds. And soon, pirates.

Philadelphia in 1658

The Annalist John Watson reflects on the earliest scenes in Philadelphia.

The Annalist John Watson reflects on the earliest scenes in Philadelphia.

Germantown Before 1730

The early German settlers of Germantown were religious intellectuals, with a Swiss background and a history of religious martyrdom.

The early German settlers of Germantown were religious intellectuals, with a Swiss background and a history of religious martyrdom.

Quakers Turn Their Backs on Power

During the French and Indian War, the Quakers who ruled Pennsylvania were forced to choose between political power and peaceful principles. They withdrew from power.

America in 1767

Philadelphia in October, 1774

Philadelphia in October, 1774

In his diary, John Adams tells of leaving Philadelphia at the conclusion of the First Continental Congress

In his diary, John Adams tells of leaving Philadelphia at the conclusion of the First Continental Congress

Philadelphia in '76

There were about 30,000 residents, the size of a small town, but it was the second largest city in the English-speaking world. Aside from wagons, there were thirty wheeled vehicles.

There were about 30,000 residents, the size of a small town, but it was the second largest city in the English-speaking world. Aside from wagons, there were thirty wheeled vehicles.

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

There were about 30,000 residents, just a small town, but it was the second largest city in the English-speaking world. Aside from wagons, there were thirty wheeled vehicles. But this is the town where decisions were made.

There were about 30,000 residents, just a small town, but it was the second largest city in the English-speaking world. Aside from wagons, there were thirty wheeled vehicles. But this is the town where decisions were made.

The Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778

As the dominant Indian Tribe in Eastern America, the Iroquois were ruthless in war. Whether egged on by the British or for their own reasons, in 1778 they remorselessly wiped out the Connecticut settlers around Wilkes-Barre.

As the dominant Indian Tribe in Eastern America, the Iroquois were ruthless in war. Whether egged on by the British or for their own reasons, in 1778 they remorselessly wiped out the Connecticut settlers around Wilkes-Barre.

Franklin's Funeral, 1790

Although it has been said there were efforts to tone it down, the Funeral of Benjamin Franklin was an important moment. Everyone in Philadelphia knew it.

Although it has been said there were efforts to tone it down, the Funeral of Benjamin Franklin was an important moment. Everyone in Philadelphia knew it.

Philadelphia in 1800

In 1800, the nation's capital moved to the District of Columbia, just as Washington, Jefferson, and Madison had hoped.

In 1800, the nation's capital moved to the District of Columbia, just as Washington, Jefferson, and Madison had hoped.

Philadelphia: Charles Dickens Gives an 1842 Viewpoint

Dickens liked Philadelphia a lot, but he was still a little patronizing.

Dickens liked Philadelphia a lot, but he was still a little patronizing.

Mark Twain Sees Philadelphia in 1853

On his first visit to Philadelphia, Mark Twain was a very young man.

On his first visit to Philadelphia, Mark Twain was a very young man.

Philadelphia City-County Consolidation of 1854

Prior to 1854, Philadelphia City was one of twenty-nine political entities within Philadelphia County. After that, it became one big city without suburbs. Growth pressure now reverses toward suburbs without a city. Political boundaries should thus shift inwardly.

Prior to 1854, Philadelphia City was one of twenty-nine political entities within Philadelphia County. After that, it became one big city without suburbs. Growth pressure now reverses toward suburbs without a city. Political boundaries should thus shift inwardly.

Philadelphia in 1876: The Centennial

A hundred years after the Declaration, Philadelphia announced to the world that is was here. And Philadelphia learned there was a lot out there in the rest of the world.

A hundred years after the Declaration, Philadelphia announced to the world that is was here. And Philadelphia learned there was a lot out there in the rest of the world.

The Definition of a Real Philadelphian (1914)

Philadelphia: A 1925 Viewpoint

Christmas Reflections

It once was a tradition to go back to the big city for Christmas shopping..

It once was a tradition to go back to the big city for Christmas shopping..

Christmas Reflections (Podcast)

George Fisher narrates one of his favorite reflections, "Christmas Reflections," on the changing face of Christmas and Christmas shopping in Philadelphia.

Fort Wilson: Philadelphia 1779

History was made at 3rd and Walnut, but so far, is unmarked.

History was made at 3rd and Walnut, but so far, is unmarked.

Quakers and Idolatry

Early Quakers were so opposed to idolatry, they wouldn"t allow tombstones.

Early Quakers were so opposed to idolatry, they wouldn"t allow tombstones.