3 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Philadelphia Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began about the time America declared Independence. The young nation faced a clean slate and boundless opportunities.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Literary Philadelphia

Literary

Literary Figures in the Philadelphia Region

John P. Marquand Born in Delaware, lived in Gardner's Cottage of Shipley/Bringhurst Estate (now, Rockwood Museum). The Late George Apley

Dudley Cammett Lunt 1896-1981. Lawyer, historian of Delaware history, lived in Rockwood. The Bounds of Delaware, Tales of Delaware Bench and Bar, Taylor's Gut in the Delaware State (Mason and Dixon), The Road to the Law Contact John P. Reid.

J. Gould Cozzens, By Love Possessed

Zane Gray

Edgar Allen Poe

E. Digby Baltzell Quaker Philadelphia and Puritan Boston

Struthers Burt Philadelphia Holy Experiment

Nathaniel Burt Perennial Philadelphians

"The Philadelphia Rosary":

Morris, Norris, Rush, and Chew,

........................................Drinker, Dallas, Coxe, and Pugh,

........................................Wharton, Pepper, Pennypacker,

........................................Willing, Shippen and Markoe

Pearl Buck The Good Earth

John Updike Run, Rabbit

James Michener Tales of the South Pacific

Abbie Hoffman

Margaret Mead Growing Up in Samoa

John O'Hara Appointment in Samara

Owen Wister The Virginian

Benjamin Franklin Autobiography

Fanny Kemble Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation 1838-1839

Silas Weir Mitchell Hugh Wynne, Quaker

J.D. Salinger

Edward Albee

REFERENCES

| Tales of the Delaware Bench and Bar: Dudley C. Lunt ASIN: B005FFGEO6 | Amazon |

Logan, Franklin, Library

|

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

Jim Greene is the librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia, and one of the leading authorities on James Logan, the Penn Proprietors' chief agent in the Colony. Since Logan and Ben Franklin were the main forces in starting the oldest library in America, knowing all about Logan almost comes with the job of Librarian. We are greatly indebted to a speech the other night, given by Greene at the Franklin Inn, a hundred yards away from the Library.

|

| James Logan |

Logan has been described as a crusty old codger, living in his mansion called Stenton and scarcely venturing forth in public. He was known as a fair dealer with the Indians, which was an essential part of William Penn's strategy for selling real estate in a land of peace and prosperity. Unfortunately, Logan was behind the infamous Walking Purchase, which damaged his otherwise considerable reputation. Logan must have been a lonesome person in the frontier days of Philadelphia because he owned the largest private library in North America and was passionate about reading and scholarly matters. When he acquired what was the first edition of Newton's Principia, he read it promptly and wrote a one-page summary. Comparatively few people could do this even today. It's pretty tough reading, and those who have read it would seldom claim to have "devoured" it.

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Except young Ben Franklin, who never went past second grade in school. The two became fast friends, often engaging in such games as constructing "Magic Squares" of numbers that added up to the same total in various ways. For example, Franklin doodled off a square with the numbers 52,61,4,13,20,29,36,45 (totaling 260) on the top horizontal row, and every vertical row beneath them totaling 260, as for example 52,14,53,11,55,9,50,16, while every horizontal row also totaled 260 as well. The four corner numbers, with the 4 middle numbers, also total 260. Logan constructed his share of similar games, which it is difficult to imagine anyone else in the colonies doing at the time.

Logan and Franklin together conceived the idea of a subscription library, which in time became the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1732. The subscription required of a library member was intended to be forfeited if the borrower failed to return a book. Later on, the public was allowed to borrow books, but only on deposit of enough money to replace the book if unreturned. We are not told whose idea was behind these arrangements, but they certainly sound like Franklin at work. More than a century later, the Philadelphia Free Library was organized under more trusting rules for borrowing which became possible as books became less expensive.

Logan died in 1751, the year Franklin at the age of 42 decided to retire from business -- and devote the remaining 42 years of his life to scholarly and public affairs. He first joined the Assembly at that time, so he and Logan were not forced into direct contention over politics, although they had their differences. How much influence Logan exerted over Franklin's plans and attitudes is not entirely clear; it must have been a great deal.

Quotes from B. Franklin, Curmudgeon

|

| Ben Franklin |

~ I guess I don't so much mind being old, as being fat and old.

~ Many foxes grow Grey, but few grow good.

~ If it is the design of Providence to extirpate these savages in order to make room for the cultivation of the earth, it seems not improbable that rum may be the appointed means.

~ A countryman between two lawyers is like a fish between two cats.

~ Remember not only to say the right thing in the right place but far more difficult still, to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.

~ The Constitution only guarantees the American people the right to pursue happiness. You have to catch it, yourself.

~ The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.

~ The man who trades freedom for security does not deserve, nor will he ever receive, either.

~

Those who govern, having much business on their hands, do not generally like to take the trouble of considering and carrying into execution new projects. The best public measures are therefore seldom adopted from previous wisdom, but forced by the occasion.

- The greatest monarch on the proudest throne is still obliged to sit on his own arse.

-

Rise and Fall of Books

| ||

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

John C. Van Horne, the current director of the Library Company of Philadelphia recently told the Right Angle Club of the history of his institution. It was an interesting description of an important evolution from Ben Franklin's original idea to what it is today: a non-circulating research library, with a focus on 18th and 19th Century books, particularly those dealing with the founding of the nation, and, African American studies. Some of Mr. Van Horne's most interesting remarks were incidental to a rather offhand analysis of the rise and decline of books. One suspects he has been thinking about this topic so long it creeps into almost anything else he says.

|

| Join or Die snake |

Franklin devised the idea of having fifty of his friends subscribe a pool of money to purchase, originally, 375 books which they shared. The members were mainly artisans and the books were heavily concentrated in practical matters of use in their trades. In time, annual contributions were solicited for new acquisitions, and the public was invited to share the library. At present, a membership costs $200, and annual dues are $50. Somewhere along the line, someone took the famous cartoon of the snake cut into 13 pieces, and applied its motto to membership solicitations: "Join or die." For sixteen years, the Library Company was the Library of Congress, but it was also a museum of odd artifacts donated by the townsfolk, as well as the workplace where Franklin conducted his famous experiments on electricity. Moving between the second floor of Carpenters Hall to its own building on 5th Street, it next made an unfortunate move to South Broad Street after James and Phoebe Rush donated the Ridgeway Library. That building was particularly handsome, but bad guesses as to the future demographics of South Philadelphia left it stranded until modified operations finally moved to the present location on Locust Street west of 13th. More recently, it also acquired the old Cassatt mansion next door, using it to house visiting scholars in residence, and sharing some activities with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on its eastern side.

|

| Old Pictures of the Library Company of Philadelphia |

The notion of the Library Company as the oldest library in the country tends to generate reflections about the rise of libraries, of books, and publications in general. Prior to 1800, only a scattering of pamphlets and books were printed in America or in the world for that matter, compared with the huge flowering of books, libraries, and authorship which were to characterize the 19th Century. Education and literacy spread, encouraged by the Industrial Revolution applying its transformative power to the industry of publishing. All of this lasted about a hundred fifty years, and we now can see publishing in severe decline with an uncertain future. It's true that millions of books are still printed, and hundreds of thousands of authors are making some sort of living. But profitability is sharply declining, and competitive media are flourishing. Books will persist for quite a while, but it is obvious that unknowable upheavals are going to come. The future role of libraries is particularly questionable.

Rather than speculate about the internet and electronic media, it may be helpful to regard industries as having a normal life span which cannot be indefinitely extended by rescue efforts. No purpose would be served by hastening the decline of publishing, but things may work out better if we ask ourselves how we should best predict and accommodate its impending creative transformation.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1470.htm

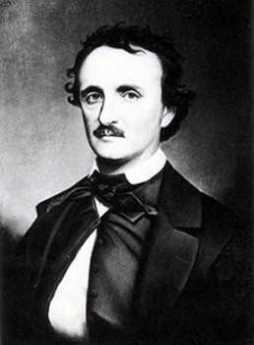

Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849

|

| Edger Allan Poe |

Between the Federalist period and the Civil War, Philadelphia quadrupled in population, mostly by Irish and black immigration responding to the urbanization induced by the Industrial Revolution. The social boundaries of this period were established by the U.S. Capital moving away to Washington, and at the other boundary, the constrained urban population was suddenly released to the suburbs by the City-County Consolidation of 1854. During that time, the Northern Liberties on the other side of Callowhillwere very close by, but nearly devoid of law and order. At least along the Delaware River, the scene was like Las Vegas as imagined by Charles Dickens. Within the increasingly congested boundaries of the city itself, tuberculosis, alcoholism, riots and religious revivalism are all mentioned prominently. While it was the time of Nicholas Biddle and the Bank, and the establishment of the Drexel empire, it was a gothic period quite adequately symbolized by Ethan Allan Poe, writing for Graham's Magazine. His father abandoned the family, his mother and later his wife died of tuberculosis, he was definitely an alcoholic and probably manic-depressive. He and Charles Brockton Brown invented the gothic novel, gothic poetry, the modern murder mystery. Poe only lived in Philadelphia for six years but lived in seven different locations, the most famous of which is now part of the National Park Service, even though it is located off Spring Garden Street. Yes, he was born in Boston but lived there only briefly, and yes, he died in Baltimore, by dropping dead in the street while traveling through. He was scarcely a prototypical Philadelphian, but he was certainly a symbol of his age.

|

| Grip the Raven |

There is a big stuffed Raven named Grip in the Free Library which belonged to Charles Dickens and is claimed to be the inspiration for Poe's Raven; it certainly has an ominous look, whatever its provenance. Poe offered his famous poem to Graham, who rejected it but gave him $15 as an act of charity. Another magazine paid him $9 to publish it. This poem was widely included in elementary school anthologies by the Philadelphia book publishing industry, and its simple repetitions with a scary atmosphere continue to be popular with children. The Murders in the Rue Morgue were the beginning of the modern murder mystery, and seem to have started Brockton Brown off on his establishment of the Philadelphia Gothic novel, echoing the whole dark and menacing Poe tradition. From the descriptions, Poe's alcohol problem was not so much related to the volume of consumption as to the violent manias which just a small quantity provoked in him. If your mother and your wife both died of tuberculosis, it's a fair bet you had it, too. At the age of 40, he was gone.

French Philadelphia

|

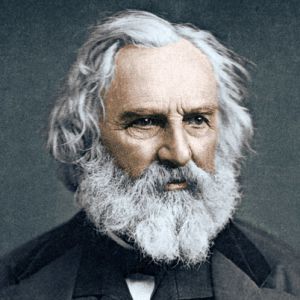

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow |

Since American relations with France are a little strained at the moment, it may not be completely welcome to hear it said that Philadelphia food is Creole. The reference is not to the several downtown French restaurants of outstanding quality, but to the two episodes when Philadelphia experienced waves of French immigration. The first of these was during the French and Indian War, when the Acadian French ("Cajun") were driven out of Nova Scotia, largely went to Louisiana and then were allowed to return. A lot of them stopped off in Philadelphia both going and coming. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow depicted, in his poem Evangeline, the tearful reunion of Evangeline and Gabriel in the hospital. And since for sixty years the Pennsylvania Hospital was the only hospital in the country, Longfellow had to put them here.

The second wave of French immigration was provoked by the guillotine in Paris, and the black revolution in French Haiti. Most people today are unaware that Talleyrand lived here, and LaRochefoucauld. The Duke of Orleans, future king of France, lived at 4th and Locust Streets, proposed to a (rich) Philadelphia lady, and was rejected by her father ("Sir, if you do not become king of France, you will be no match for her, and if you do become king, she will be no match for you.") Napoleon's brother Joseph lived at 9th and Spruce, and one of his marshals lived at 6th and Spruce. Really. Talleyrand had a deformed foot, and this somehow made him pals with Governor Morris who had a wooden leg. This friendship was part of the reason the Louisiana Purchase was possible, because they shared the favors of the same French lady, and had frequent occasion to meet. Both Franklin and Jefferson were ambassadors to France, it may be remembered, and for a while, Jefferson was quite a fan of the French Revolution, although the treatment of LaFayette by the French Revolutionaries did not exactly encourage that. The French treated Franklin like a God, but then so did Mozart and the King of England, and Franklin harbored many bitter memories of the French and Indian War all the while he was romancing the French into bankruptcy to pay for our revolution. The French refugees from Haiti brought Yellow Fever with them, and Dengue too, thus definitively terminating Philadelphia's hope of remaining the permanent capital of the nation.

It was during this Francophone period that Philadelphia cuisine acquired some characteristics which allow some food historians to call it Creole. Philadelphia Pepper Pot soup, for example, substituted tripe for terrapin. Those who know about these things say that many dishes now thought to be distinctly Philadelphian in fact had a French origin.

Fanny Kemble

|

| Fanny Kemble (Sully) |

Frances Anne Kemble, universally known as Fanny, was just about the most magnificent Philadelphia woman of the Nineteenth Century. She spent much of her time abroad and others claimed her, but she was ours. Coming from a famous English theater family, the niece of Mrs. Siddons and the daughter of the founder of Covent Gardens, she quickly rescued the failing family fortunes by becoming the most striking Shakespearean ingenue of the time. It took very little time for her to know Lord Byron, Thackeray, and various other luminaries of the literary and artistic world of Europe, along with Queen Victoria. One might as well say she knew everybody unless one made the point that everyone knew her.

|

| Pierce Butler |

On a theatrical grand tour of America she met and married the Philadelphian Pierce Butler, one of the richest bachelors in the nation, heir to huge estates in Georgia. She had plenty of other choices, including the most dashing and romantic devil of the century, Trelawny. That glamorous friend of Byron's had been the one to drag Percy Shelley's body from the ocean, and was surely the greatest heartthrob of the century. Toward the end of her life, Fanny demonstrated the range of her appeal by totally subjugating the intellectual novelist Henry James, who was 34 years younger than she was. Her portraits by Sully now hang in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and in the Rosenbach Museum. Although Sully was said to have glamorized her a bit, her movie star qualities are evident. But appearance alone could not have mesmerized Henry James, known in literary circles as The Master. She was evidently one of those powerfully self-assured personalities encountered from time to time, who dominates every conversation, fills every room she enters, inspiring admiration rather than jealousy. As a youth, she was enchanting, as a mature woman, magnificent. Henry James described her as having "an incomparable abundance of being."

But this was not just another Cleopatra. Fanny Kemble had two personal achievements of enduring note. Because of health limitations, she went beyond being a Shakespearean actress to inventing a style of a public reading of Shakespeare, taking all the parts herself. She and Dr. Samuel Johnson were the two successive forces transforming Shakespeare's reputation from the quaint playwright of the past into the permanent towering figure of the English language.

Her other achievement destroyed her private life. As the wife of the owner of a thousand slaves, she led the attack on slavery before the Civil War. During the War, her passionate defense of emancipation was the main factor in persuading the British Government to refuse badly needed loans to the Confederacy. However, the publication of her journals was the last straw in a tumultuous marriage, and Pierce Butler divorced her, taking custody of their daughters, exiling her to England. Southern plantation owners were always short of cash, and realistically one has to acknowledge the strain of demanding to emancipate a thousand slaves, each one worth a thousand dollars. In one of the supreme ironies of a tragic situation, the forced sale of the slaves compelled the Butlers to liquidate an asset just before it was going to be destroyed by wartime events. Butler died in 1863, but she had done him a financial favor.

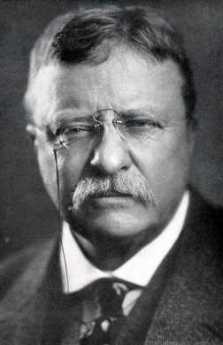

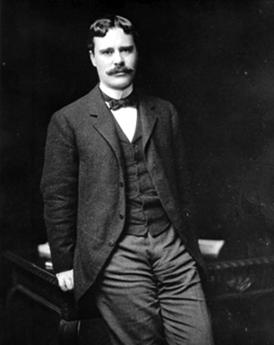

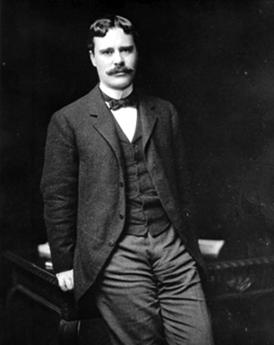

Fanny's daughter married Dr. Caspar Wistar, of Grumblethorpe and the grounds of present LaSalle College. Her grandson was Owen Wister, the college roommate of Teddy Roosevelt, later the author of The Virginian. Famous for the phrase "If you say that to me, smile", Owen Wister and his roommate created the fable of the romantic cowboy which still dominates movies and fiction, and, from time to time, the Presidency of the United States.

Fanny Kemble Takes the Train South, in 1838

The "Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839" raised strong feelings against slavery, particularly in Frances Anne Kemble's native England. At the outset of her book, Fanny Kemble describes what it was like to travel on American railroads in 1838.

On Friday morning December 21, 1838, we started from Philadelphia, by railroad, for Baltimore. It is a curious fact enough, that half the routes that are traveled in America are either temporary or unfinished -- one reason, among several, for the multitudinous accidents which befall wayfarers. At the very outset of our journey, and within scarce a mile of Philadelphia, we crossed the Schuylkill, over a bridge, one of the principal piers of which is yet incomplete, and the whole building (a covered wooden one, of handsome dimensions) filled with workmen, yet occupied about its construction. But the Americans are impetuous in the way of improvement and have all the impatience of children about the trying of a new thing, often greatly retarding their own progress by hurrying unduly the completion of their works, or using them in a perilous state of incompleteness. Our road lay for a considerable length of time through flat low meadows that skirt the Delaware, which at this season of the year, presented a most dreary aspect. We passed through Wilmington (Delaware) and crossed a small stream called the Brandywine, the scenery along the banks of which is very beautiful. For its historical associations, I refer you to the life of Washington. I cannot say that the aspect of Wilmington, as viewed from the railroad cars, presented any very exquisite points of beauty....

And first, I cannot but think that it would be infinitely more consonant with comfort, convenience, and common sense, if persons obliged to travel during the intense cold of an American winter in the Northern states, were to clothe themselves according to the exigencies of the weather, and so do away with the present deleterious custom of warming close and crowded carriages with sheet iron stoves, heated with anthracite coal. No words can describe the foulness of the atmosphere...Of course, nobody can well sit immediately in the opening of a window when the thermometer is twelve degrees below zero yet this, or suffocation in foul air is the only alternative...

We pursued our way from Wilmington to Havre de Grace on the railroad, and crossed one or two insets from the Chesapeake, of considerable width, upon bridges of a most perilous construction, and which, indeed, have given way once or twice in various parts already. They consist merely of wooden piles driven into the river, across which the iron rails are laid, only just raising the train above the level of the water. To traverse with an immense train, at full steam-speed, one of these creeks, nearly a mile in width, is far from agreeable...At Havre de Grace we crossed the Susquehanna in a steamboat, which cut its way through the ice an inch in thickness with marvelous ease and swiftness and landed us on the other side, where we again entered the railroad carriages to pursue our road.

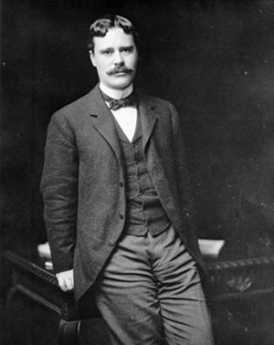

Harvard Progressives in Philadelphia

|

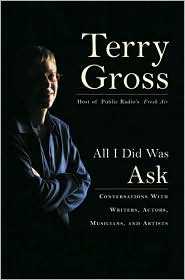

| Theodore Roosevelt |

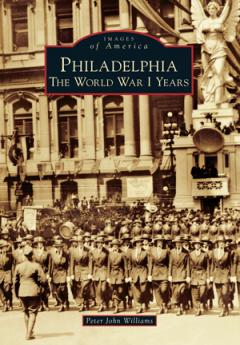

The Progressive movement of the early 20th century is most concisely viewed as a futile social reaction to the vast changes in America caused by urbanization and industrialization after the Civil War. The transcontinental railroad threatened to destroy the wild, wild West, but the enduring environmental movement had overtones of even greater hostility toward industrialization, the cause of it all. In this sense, it joined forces with socialist and labor reform movements, in hating the newly rich, the spoilers, the Robber Barons. It briefly shared sympathies with anti-immigrant groups, while simultaneously expressing great sympathy with the decisions of the people, as opposed to corrupt politicians. There was a strong Calvinist streak in Progressivism, linked back to New England and Harvard its intellectual center. Regardless of any other contradiction, it reflected the viewpoint of Theodore Roosevelt. Teddy Roosevelt, "that damned cowboy" in the view of conservatives, did not invent the ideas of Progressivism, but he surely personified them, illustrated them in action. This confused turmoil of resentments was knocked off the front pages by a real threat to European civilization, the First World War. A terrifyingly well organized German war machine took the place of Robber Barons as a symbol of what was wrong with the world. The crash of 1929 and its ensuing long depression finally put an end to older controversies; it pushed the "reset" button.

|

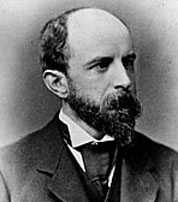

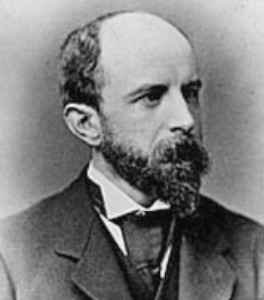

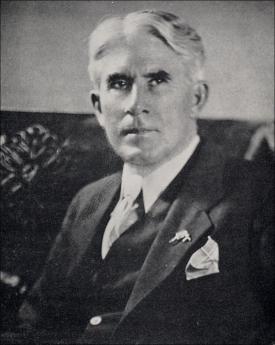

| Henry Brooks Adams |

To understand the position of Philadelphia's upper crust during the Progressive era, four or five names need to be fleshed out. Owen Wister and J. William White would be important Philadelphia links to the Bostonians Henry Adams and Henry James. All of them were leading literary figures, and all of them were close friends of Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt, it might be recalled, was the author of thirty-four books. This little group of literary giants were members of the leading families of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia; what they said, mattered. Although today Owen Wister is mainly known as the author of The Virginian, the first of the cowboy stories of the Wild West, he was, in fact, an observer of the social climates of not only the West, but the deep South (Lady Baltimore ), and the East Coast ( Romney). Some idea of his political leanings can be gleaned from his presidency of the Immigrant Restriction Society, and the authorship of an article called Shall We Let the Cuckoos Crowd Us From Our Nest . Wister has been called "the best born and bred of all modern writers", referring to his descent

James A. Michener (1907-1997)

|

| James A. Michener |

James Michener seemed headed for a recognizably Quaker life until show business rearranged his moorings. He was raised as a foundling by Mabel Michener of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, under circumstances that were very plain and poor. Many of his biographers have referred to his boyhood poverty as a defining influence, but they seem to have very little familiarity with Quakers. When the time came, this obviously very bright lad was offered a full scholarship to Swarthmore College, graduated summa cum laude, went on to teach at the George School and Hill Schools after fellowships at the British Museum. And then World War II came along, where he was almost but not exactly a conscientious objector; he enlisted in the Navy with the understanding he would not fight.

While in the Pacific, he had unusual opportunities to see the War from different angles, and wrote little short stories about it. Putting them together, he came back after the War with Tales of the South Pacific. Much of the emphasis was on racial relationships, the Naval Nurse who married a French planter, the upper-class Lieutenant (shades of the Hill School) who had a hopeless affair with a local native girl that was engineered by her ambitious mother, as central characters. Michener himself married a Japanese American, Mari Yoriko Sabusawa, whose family had been interned during the War. There are distinctly Quaker themes running through this story.

And then his book won a Pulitzer Prize, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein made it into a Broadway musical hit, then a movie emerged. The simple Quaker life was then struck by the Tsunami of Broadway, Hollywood, show biz and enormous unexpected wealth. Just to imagine this simple Bucks County schoolteacher in the same room with Josh Logan the play doctor is to see the immovable object being tested by the irresistible force. Michener retreated into an impregnable fortress of work. He produced forty books, traveled incessantly, ran for Congress unsuccessfully, and was a member of many national commissions on a remarkably diverse range of topics. Although he lived his life in a simple Doylestown tract house, he gave away more than $100 million to various charities and educational institutions.

In his 91st year, he was on chronic renal dialysis. He finally told the doctors to turn it off.

Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia

|

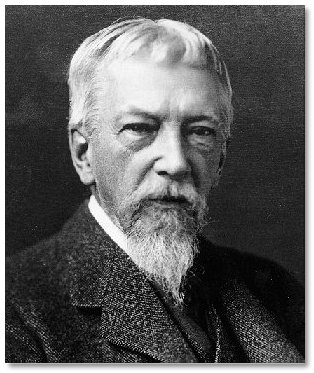

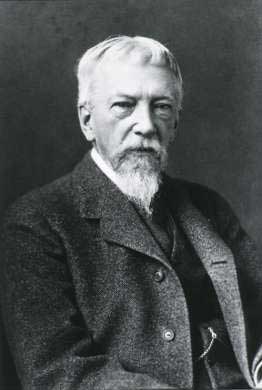

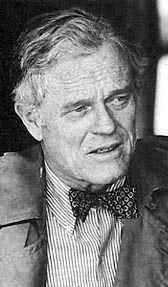

| Professor Digby Baltzell |

Digby Baltzell had something of the defiant rebel in him. He surely didn't imagine his employer, the University of Pennsylvania, was pleased to have him a document that Harvard is a better college than Penn. Nor were fellow members of the Philadelphia Club pleased to confront scholarship that his city's gentry was too devoted to money-making to accept the ardors of public leadership. Nor would his relatives in the Society of Friends enjoy accusations their religion impaired the pursuit of excellence in all fields of the city's endeavor. Later articles will here take up some unfair assaults, and defend Quaker simplicity and Peace Testimony. Some blame must, of course, be shared, some mitigating circumstances acknowledged. And let it be said in Baltzell's support that it truly is remarkable how many cultural features do get passed down for ten or more generations. Or even longer; look at the persistence of ancient Chinese, Indian, Esquimo, Viking, Roman, Christian and other cultural heritage. The Quakers got to Pennsylvania early, they are now vastly outnumbered. Many Quaker ideas continue to influence present inhabitants, some ideas probably hold us back. Substitute "Puritans of Boston" for "Quakers" in the foregoing sentence, and conclude by saying "some of those ideas probably give Bostonians an edge". Those two rather unexceptional declarations summarize a controversial book, although they do not completely capture its overall censorious flavoring.

To a certain extent, Digby is his own worst enemy. While alive, he was one of the world's most charming raconteurs, a walking encyclopedia of local lore. Like a good docent in a museum, he could walk into a room hung with portraits, and charm any audience for an hour; presumably, his sociology lectures at Penn held the same magnetism for his classes. In a book for popular readers, however, it is overdone to go on about the same point for six hundred pages. He needed a better editor, or perhaps he needed to permit a better editor to make him restrain his tendency to multiply illustrations beyond the point where the reader loses the thread of the argument. Not all readers will agree with his argument; they can only be legitimately defeated by focused argument. That's perhaps unrequired of college professors holding the power of grade-point averages over nineteen-year-olds, but it is expected of conversation with other adults. If an editor wants to sell books to a general bookstore audience, he should induce authors to overcome the take-it-or-leave-it habit.

As a general reaction to this book, Baltzell seems to think Quakers do not want to be rich and that consequently, latecomers into the region tend to share this feeling. My own view is that Quakers see they can have almost all of the value of being moderately rich -- by disdaining the trivial luxuries of the middle classes. They do not exactly renounce fame and power but are unwilling to gamble much or sacrifice much, in order to enjoy the comparatively small exhilaration of being very rich. They are now no longer surrounded by junior versions of themselves, but by bank-robbing Willie Suttons who readily attack Quakers for being where the money is, and appear to be pushovers at that. When Quakers then promptly demonstrate they are not pushovers at all, they are treated like outsiders in their own town. In many ways and at most times, the populist crowd gives up trying to understand Quakers and decides they must somehow always behave in ways that others would not. It's hard to achieve much deference in such an environment.

Many of Baltzell's important insights grew out of his position as a Philadelphia and academic insider; he personally knew many of the people he described. However, such an infiltrator runs the constant risk of being viewed as a tattle-tale, so a cover is required. Batzell's technique involved frequent use of quotations from others, not so much to prove a point as to rephrase it. This is another feature of the book which might have benefited from a hard-nosed editor. However this is how he wanted it, and in a post-publication revision, here is a condensation of how he summarizes his argument:

When studied with any degree of thoroughness, the economic problem will be found to run into the political problem, the political problem, in turn, run into the philosophical problem, and the philosophical problem itself to be almost indissolubly bound up at last with the religious problem.

--Irving Babbitt

In the South, ....left-wing Quakers came to the fore in the pine barrens of North Carolina-- to this day, North Carolinians speak of their state as "a valley of humilities between two mountains of conceit."

--E. Digby Baltzell

The world is only beginning to see that the wealth of a nation consists more than anything else in the number of superior men it harbors.

-- William James

I believe that ambitious men in democracies are less engrossed than any other with the interests and judgments of posterity; the present moment alone engages and absorbs them...and they are much more for success than for fame. What appears to me most to be dreaded, that in the midst of the small, incessant demands of private life, ambition should lose its vigor and its greatness.

-- Alexis de Tocqueville

Our rulers today consist of a random collection of successful men and their wives. ....They have been educated to achieve success, but few of them have been educated to exercise power. Nor do they count with any confidence upon retaining their power, nor of handing it on to their sons. They live therefore from day to day, they govern by ear. Their impromptu statements of policy may be obeyed, but nobody seriously regards them as having authority.

--Walter Lippmann

Equalitarians holding...extreme views have tended to believe that men of great leadership capacities, great energies or greatly superior aptitudes are more trouble than they are worth.

--John W. Gardiner

In the Jacksonian era in this country, equalitarianism reached such heights that trained personnel in the public service were considered unnecessary...Thus, in the West, even licensing of physicians was lax, because not to be lax was apt to be thought undemocratic.

--Merle Curti

In the late eighteenth century we produced out of a small population a truly extraordinary group of leaders-- Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, Monroe, and others. Why is it so difficult today, out of a vastly greater population, to produce men of that character?

--John W. Gardiner

It is nevertheless certain that the high quality of Virginia's political leadership in the years when the United States was being established was due in large measure to those very things which are now detested. Washington and Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, Mason, Marshall, and Peyton Randolph, were products of the system which sought out and raised to high office men of superior family and social status, of good education, or personal force, of experience in management: they were placed in power by a semi-aristocratic political system.

--Charles S. Syndor

Another clue to the relationship between hierarchy and leadership is suggested by Gardner's list of the Founding Fathers. All of these men were reared in Massachusetts or Virginia; none was reared in the colony of Pennsylvania, though Philadelphia was the largest city in the new nation and contained perhaps the wealthiest, most successful, gayest, and most brilliant elite in the land. Not only had Pennsylvanians little to do with taking the lead in our nation's founding, but the state has produced very few distinguished Americans throughout our history...I shall concentrate here on the commercial cities of Boston and Philadelphia, whose great differences in leadership and authority were far more likely to reflect differences in ideas and values.

--E. Digby Baltzell

Whatever else ...America came to be, it was also an experiment in constructive Protestantism.

--H. Richard Niehbur

All this is only to say that man is a product of his history, where nothing is entirely lost and little is entirely new.

--E. Digby Baltzell

For the wine of New England is ...more like the mother-wine in those great casks of port and sherry that one sees in the bodegas of Portugal and Spain, from which a certain amount is drawn off each year, and replaced by an equal volume of the new. Thus the change is gradual, and the mother wine of 1656 still gives bouquet and flavor to what is drawn in 1956.

--S.E. Morison

New Englanders, ambitious beyond reason to excell.

--Henry Adams

Henry Adams Pennsylvania became the ideal state, easy, tolerant and contented. If its soil bred little genius, it bred less treason. ... To politics, the Pennsylvanians did not take kindly. Perhaps their democracy was so deep an instinct that they knew not what do to with political power when they gained it; as though political power was aristocratic in its nature, and democratic power a contradiction in terms.

--Henry Adams

The reproach I address to the principles of equality is that it leads men to a kind of virtuous materialism, which would not corrupt, but would enervate the soul, and noiselessly unbend its springs of action.

--Alexis de Tocqueville

In our egalitarian age of mistrust, trustworthy men of great ability are increasingly refusing to run for public office or to serve in positions of authority and leadership in our society...In the rest of this book, I shall try to show how and why the Quaker city of Philadelphia, in contrast to Puritan Boston, has suffered from that virus of virtuous materialism for almost three centuries and how its best men, on the whole, have seldom sought public office or positions of societal authority and leadership outside business.

--E. Digby Baltzell

REFERENCES

| Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia: E. Digby Baltzell. ISBN-13: 978-1560008309 | Amazon |

The Franklin Inn

Founded by S. Weir Mitchell as a literary society, this little club hidden on Camac Street has been the center of Philadelphia's literary life.

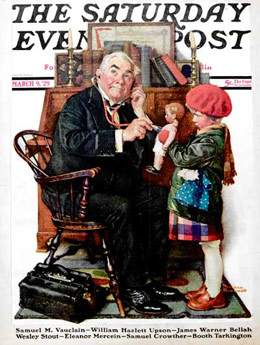

|

Camac Street is a little alley running parallel to 12th and 13th Streets, and in their day the little houses there have had some pretty colorful occupants. The three blocks between Walnut and Pine Streets became known as the street of clubs, although during Prohibition they had related activities, and before that housed other adventuresome occupations. In a sense, this section of Camac Street is in the heart of the theater district, with the Forrest and Walnut Theaters around the corner on Walnut Street, and several other theaters plus the Academy of Music nearby on Broad Street. On the corner of Camac and Locust was once the Princeton Club, now an elegant French Restaurant, and just across Locust Street from it was once the Celebrity Club. The Celebrity club was once owned by the famous dancer Lillian Reis, about whom much has been written in a circumspect tone, because she once successfully sued the Saturday Evening Post for a million dollars for defaming her good name.

|

| The Franklin Inn |

Camac between Locust and Walnut is paved with wooden blocks instead of cobblestones because horses' hooves make less noise that way. The unpleasant fact of this usage is that horses tend to wet down the street, and in hot weather you know they have been there. Along this section of narrow street, where you can hardly notice it until you are right in front, is the Franklin Inn. The famous architect William Washburn has inspected the basement and bearing walls, and reports that the present Inn building is really a collection of several -- no more than six -- buildings. Inside, it looks like an 18th Century coffee house; most members would be pleased to hear the remark that it looks like Dr. Samuel Johnson's famous conversational club in London. The walls are covered with pictures of famous former members, a great many of the cartoon caricatures by other members. There are also hundreds or even thousands of books in glass bookcases. This is a literary society, over a century old, and its membership committee used to require a prospective member to offer one of his books for inspection, and now merely urges donations of books by the author-members. Since almost any Philadelphia writer of any stature was a member of this club, its library represents a collection of just about everything Philadelphia produced during the 20th Century. Ross & Perry, Publishers has brought out a book containing the entire catalog produced by David Holmes, bound in Ben Franklin's personal colors, which happen to be gold and maroon, just like the club tie.

The club was founded by S. Weir Mitchell, who lived and practiced Medicine nearby. Mitchell had a famous feud with Jefferson Medical College two blocks away, and that probably accounts for his writing a rule that books on medical topics were not acceptable offerings from a prospective member of the club. So there.

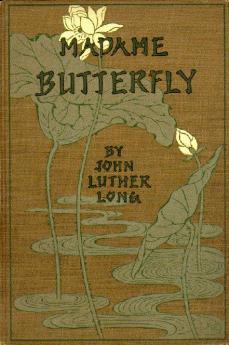

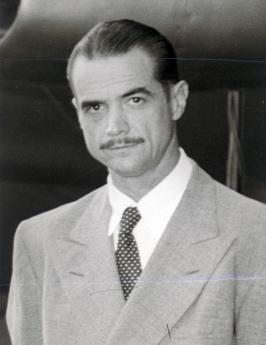

The club has daily lunch, with argument, at long tables, and weekly round table discussions with an invited speaker. Once a month there is an evening speaker at a club dinner, with the rule that the speaker must be a member of the club. Once a year, on Benjamin Franklin's birthday, the club holds an annual meeting and formal dinner. At that dinner, the custom has been for members to give toasts to three people, all doctors, including Dr. Franklin, Some sample toasts follow: The hundred years war, the thirty years war, the seven years war, and other European disagreements made it difficult to import wine to England, turning the wine import trade to Portugal. Port wine was, of course, prominent, but the best wine of all came from the Portuguese colony of Madeira. The island of Madeira is closer to Africa than to Portugal, so the triangular slave trade made it easy to import Madeira wine to the British colonies in America. The eastern seaboard of America had no grape culture of any note, so the beverage trade centered on rum, whiskey, beer, and Madeira. George Washington is widely reported to have had half a bottle of Madeira every day for lunch, for example. The other evening at the Franklin Inn Club, a traditional Philadelphia Madeira party filled the hall, and the membership was brought up to date on some of the traditions and finer points of the occasion. In the first place, the Franklin Inn was founded by S. Weir Mitchell. Mitchell, in his spare time as Father of Neurology, had written a short story called The Madeira Party which worked in a large number of details about what was what about Madeira, ending with ribald tipsiness. Nathan Steven, a well-known wine authority, instructed the group in the various types of grape and vintage, and other members who have summered in Madeira related current conditions. Because the volcanic island is a favorite place for visitors, particularly Englishmen, real estate is at such a premium that most vineyards have only one or two acres of grapes. The wineries whose names are on the bottles pick up the crop from these local growers and take it on from there. This seems as good as any other explanation for the current high prices of the wine. However, a century ago a disease wiped out the French and Portuguese vineyards, who were forced to beg back some exported grapevines from California to get back in business. So, one wonders about the scarcity claim. It is related that a number of cargoes of Madeira, particularly those of John Hancock of Boston were caught being smuggled to the colonies, and got returned. It was discovered that the taste of the wine was greatly improved by the tumult so that each vintner experimented with various methods of agitating and heating the wine to produce a particular brand. Madeira, like sherry, is a fortified wine, with various proportions of grain alcohol and brandy added in secret formulas. On one point there is general agreement, that if fortified wines are aged for long enough periods, eventually they all taste alike. There thus has emerged a tricky business of aging the wine long enough for the vintage of the wine to match the age or anniversary of the person being honored by the gift. Fifty years is the tricky goal; it's the most popular gift, but perilously close to the point where you can't tell if it is sherry or Madeira. There are four main varieties of Madeira (brand names are something else), getting progressively sweeter, darker colored and more expensive as they age. Malmsey, in a barrel of which Shakspere portrayed the royal princes being drowned, is claimed to be the very best. Some people regard it as too sweet, however. At proper Madeira party, each variety is served with a different course of terrapin or whatever. The President of the Franklin Inn read off the instructions for cooking the traditional first course of jellied boiled boar's head, and the guests agreed that modern tastes called for a substitute. After the reading of Mitchell's short story, the group added a new tradition of singing Flanders and Swann's ribald song, "Have Some Madeira, m'dear". Chuck Barber, the current President of the Green Tree Insurance Company, added an entirely new historical slant. The Insurance Company is well known for having the best dinner in town at its meetings since directors of insurance companies don't do much. At the dinner in 1799, the news was brought in that George Washington had just died. A member rose to propose what has become an annual toast in Madeira, "To President Washington!" In time, S. Weir Mitchell became a member of the board, and the famous short story was the outcome which firmly fixed the rules of the Philadelphia Madeira Party. Bill Madeira was called on to verify this history, but he protested that his family name was derived from the wine, not the other way around. It seems appropriate to add another historical note. Benjamin Franklin, after whom the club is named, suffered severely from gout. Although some sort of association with liquor had been mentioned as far back as Hippocrates, Franklin's powers of observation and his fame as a scientist placed him in a position to make it an irrefutable doctrine that gout was a medical penalty for drinking liquor. It was, of course, Madeira that old Ben was drinking, and it was the rule that Madeira was transported in lead-lined kegs. The Green Tree has some of the old kegs if you doubt it. Franklin's observation was acute, but what he was reporting was the effect of the lead poisoning, not of the wine. Few seem to have commented much on the connection between the death of the Saturday Evening Post and the subsequent decline of the book publishing business. The Curtis Publishing Company published books, of course, but that's only a small part of the matter. The general-interest magazines, the Post in particular, were places where authors built their reputations, often long before they had started writing their books. The Post would run eight or more long articles each week, and at least two serials. From the parochial point of view of the weekly magazine, a serial was a teaser, getting the reader interested and eagerly looking forward to the next installment and the next after that. Another way of looking at it, however, was as one very long piece, larger than a magazine article, but not as big as a book. Sometimes, an eight- or ten piece serial was longer than a small book. This was a wonderful incubator for new authors, and for advance publicity for established authors planning a forthcoming book on the same topic. The big magazines paid pretty well for articles, so writing for the Post was a good way for an author to support himself during the long famines between big books. The general interest magazine wasn't designed for the purpose of supporting the book publishing industry, but it definitely evolved that way. With the disappearance, of not just the Post but of all general interest weekly magazines, the dynamics are now a lot clearer. A new author of a book today has a terribly difficult time establishing a name and a following. The striking thing is that the advent of the home computer has caused an enormous outpouring of new, excellent, manuscripts which cannot find a publisher because it's so hard to get a first-book author established. In 2006, over two hundred thousand new books were published, and many obscure titles were actually quite good books. With shorter print runs as the market gets splintered, the cost per book has skyrocket Dutch and German companies, plus a vast number of small self-publishing enterprises. Much of this sad phenomenon has been blamed on TV, or the Internet, or the school systems. You just can't get people to read and write, these days it is said, but don't believe it. There are dozens of books languishing today that would have competed very effectively with Hemingway and Dreiser and Aldous Huxley. What's much harder is to get a readership assembled for a new author without spending a king's ransom on hype and publicity; if you are going to invest that much money, the business imperative is to invest it on trash, because trash really will sell if you hype it enough. High-class literature is supposed to sell itself. Every new author is shocked to discover that it takes a full year for his manuscript to wend its way into the bookstores if you can find a bookstore. It doesn't take that long to edit and design a book. It takes that much time to arrange the publicity, and pace its appearance for the book fairs, for the Christmas season, and the reviewers. You can give a free book to a reviewer who truly means to read it, but he may not read it for months. Most book distributors and sellers will not accept a book until they see what the reviewers say. It takes a long time, it costs a lot of money, and it often is unsuccessful. It's all pretty pathetic, compared with sending a chapter to the Saturday Evening Post, getting paid to put your author in front of ten million readers. There are two ways of looking at the love affair of Pinkerton, the dashing Philadelphia naval officer, and Madame Butterfly, the beautiful Japanese geisha. John Luther Long wrote about it one way, while Puccini somehow portrays it differently, even though Long collaborated on the Libretto of the opera. Puccini, of course, was himself a famous libertine, tending to follow the typical belief of such men that women somehow enjoy being victimized. Long in real life was a Philadelphia lawyer, trained to keep a straight face when people relate what messes they have got into. If you know the story, you can see Long in the person of Sharpless, the consul. Sharpless is definitely meant to be a Philadelphia name. Long was one of the early members of the Franklin Inn, and it is related he wrote much of his successful play at the tables of the club on Camac Street. David Belasco was the "play doctor" who knew how to make a good story fill theater seats. Even after Belasco's polishing, the play came through as a portrayal of the well-born gentleman who had been trained to regard foreign girls as just what you do when you are away from home. His real girlfriend, the beautiful Philadelphia aristocratic woman in a spotless white dress, was the sort you expected to marry. In just a few sentences of Long's play, this woman comes through as just about as distastefully aloof to foreign women as it is possible to be while remaining rigidly polite about it. Butterfly sees this at a glance, knows it for what it is, and knows it is her death. Her duty immediately is "To die honorably, when one can no longer live with honor". It is Puccini's genius to take this story of how two nasty Americans destroy an honorable Japanese girl and using that same story with the same words, make it into a romantic woman being destroyed by a hopeless, helpless love affair. The power of the music overwhelms the story and sweeps you along to the ending. Even if you feel like Long/Sharpless, dismayed and disheartened by watching some close acquaintances doing things you know they shouldn't. When Puccini's opera comes to Philadelphia every year or so, the Franklin Inn has a party for the cast, one of the great events of the Philadelphia intellectual scene. Somehow, the full intent of Luther Long's work never seems to come out. Meanwhile, Ginger Rogers, who was also engaged to Howard Hughes at one point, was making a great name for herself as the star of Christopher Morley's Kitty Foyle. Morley's Haverford experience taught him somewhat more respect for the Philadelphia Gentleman than Barry ever had, while his experience at the Curtis Publishing Company also made him appreciate the smart and plain-spoken Philadelphia girls from working-class districts. Highborn Philadelphia women are only sketchily imagined by Morley, except they somehow fail to appeal to his manly fictional cricket-player from the Main Line. As matters turned out, Katy lost to Kitty. Although Hepburn was surely the more talented actress, eventually winning five Academy Awards, Ginger Rogers walked away with the 1940 Oscar for her interpretation of a working-class Philadelphia lady. Either way it turned out, of course, Howard Hughes was bound to be a happy fellow. And yes, in 1956 Grace Kelly was the star of High Society, a renamed version of the Philadelphia Story for which, remember, Katherine Hepburn still controlled the rights. The film was a mediocre performance, just a little short of embarrassing. But however inexact all three of these portrayals may have been, there is little doubt that Philadelphia society moved a bit in their direction, involuntarily living up to an image created by three observers who seemed to their own observers to retain hostility traceable to their own undefined turmoils. Philip Barry stacks the deck somewhat, portraying the leading lady as movie audiences during the Depression were likely to fantasize, indulging a luxury only a rich girl would supposedly be careless about. She rejects the colorless rich suitor out of hand. But while her remaining choice between a charming magazine writer and a charming playboy is made to seem a closer call, it really never makes our Philadelphia Cleopatra hesitate very long. In the single editorial comment, the play's author permits himself, is tucked the snarl, "She's a lifelong spinster, no matter how many times married." That's New York talking. Bitter, bitter. REFERENCES In 1947, Howard Hughes was summoned to Washington to testify at a Senate hearing. Claude Pepper, Democrat of Florida, was in the chair, clearly angry about Hughes' conduct of munitions contracts, including flagrant non-performance. Three wooden flying boats had been commissioned for $18 million but not produced, people had been killed in crashes of test planes, and the newspapers were full of obscure allusions to unspecified wrong-doing in high places. Although the Hughes hearings were front page news for weeks, in those days it was only necessary to walk in and sit down if you wanted to watch them. Under the circumstances, it would have been understandable if Hughes had been reduced to a trembling mumbler, probably advised to "take" the Fifth Amendment with every question. Congressional chairmen, particularly Claude Pepper, quite regularly grandstand and bully the helpless witness at hearings like this, since it portrays them to the voters as heroic defenders of the public interest, and could even forward their chances of becoming a Presidential candidate. Hughes the scapegoat seemed to be in for a public flogging. The first step was to haul him before the committee and then keep him waiting for an hour or so, while the members attended to important public business, maybe even had to go for a roll-call vote or something. You could tell that things were not going according to the usual script when Hughes himself arrived quite late, accompanied by quite a large staff or retainers. When Pepper still delayed the hearing, Hughes called for a newspaper and elaborately read the comic pages. The Texas swashbuckler didn't look the part. His accent and tailoring reflected a New England boarding school, and while his mustache resembled that of his friend Errol Flynn, he had a voice like a lion and lightning retorts that would do credit to Bill Buckley. Reminding the Chairman that he had been deafened in the crash of a racing plane, he asked him to repeat the question. Sorry, please repeat it again. And again, and again. Pepper was beside himself. Flustered, Pepper tried to reverse the treatment. Senator, I have already answered that question. Well, answer it again. No, I stand on my previous testimony. I forget what you said. Have the stenographer read it to you. Her transcript is not complete. Very well, my own secretary will read it back to you. As if to demonstrate that he hadn't defrauded the government, Hughes, who always test-piloted his own planes, flew the H-4 about a mile in less than a minute during what was supposed to be a taxiing test on November 2, two months after his congressional testimony. In another strange and unexplained footnote, the Glomar Explorer was a ship built in Philadelphia and used in Project Jennifer in an attempt to salvage a sunken Russian nuclear submarine and discover any secret technology it might contain. This was long past the time when Hughes was supposed to be disgraced and banished from Government contracts. The Senate hearings obviously had no effect on his status, and indeed might even have been entirely staged to mislead the Russians and others. Like so many things in his life, this episode has no readily obvious explanation. Only in retrospect is it possible to see that Hughes was involved in lots of top-secret matters, and the bravado of his defiance -- not to say contempt of Congress -- might have had roots in some sure knowledge Pepper would not dare touch him. The CIA commissioned him to build the Glomar Explorer to find a sunken Russian submarine, using a phony story of manganese recovery. The supposed political victim of the much later Watergate break-in, Larry O'Brien, is said to have once been a Hughes employee; on the other hand, Hughes was very close to the Nixon Administration. There were inevitably many ties between his Las Vegas gambling empire and Cuban underworld figures, as well as Hollywood figures. Hughes was an owner of the Dallas movie theater where John Kennedy's murderer Lee Oswald tried to hide and was captured. It is not possible to judge Howard Hughes by the usual standards; this eccentric billionaire was capable of doing unimaginable things and it will be remarkable if spectacular news about him ends with his death. Boker, George Henry, (1824-1890), Section A, Lot 91. Poet and dramatist. Helped led its Civil War propaganda Activities. Bradford, Andrew Section W, Lot 231 Andrew Bradford (1688-1742) published Philadelphia's first newspaper. Brown, Charles Brockden, (January 17, 1771 - February 22, 1810), an American novelist, historian, and editor of the Early National period, is generally regarded by scholars as the most ambitious and accomplished US novelist before James Fenimore Cooper. Bullitt, John Christian,(1824-1902)Section P, Lot 52. Lawyer and author of the Philadelphia City Charter. Childs, George William.(1829-1894)Section K, Lot 337. Publisher of Victorian best sellers and one of Philadelphia great 19th century newspapers-the Public Ledger Conrad, Robert, (1810-1858). Section 14, Lot 266. A literary figure who served as first Mayor of the Consolidated City of Philadelphia. Cummings, Brig. Gen. Alexander (1810-1879) Section I, Lot 224 Founded the Evening Bulletin, oversaw procurement and raised troops in Civil War. Governor of the Colorado Territory. Nicknamed "Old Straw Hat." Curtis, Louisa Knapp. (1852-1910)River Section, Lot 31. Editor of the Ladies Home Journal. Duane, Mary Morris (Section L, Lot107-112) was a Poet. Elverson, James. (1828-1911). Section T. Lot 41. Developed the Inquireras a major newpaper. Fagan, Frances.(Fanny)(1834-1878) Section G, Lot 272, first daughter of John Francis Fagan by his first wife, Mary (Armstrong). Fagan committed suicide and was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery, on 2 February 1878. Poet. Godey, Louis Antoine. (1804-1878) Section WXYZ Oval. Lot 3. Publisher of America's first great magazine for women-Godey's Lode's Book. Hale, Sarah Josepha. (1788-1879). Section X, Lot 61. Editor of Godey's Lady's Book, a crusader for women's medical education, and the person chiefly credited with establishing Thanksgiving as a national holiday. Hildeburn, Mary Jane,(1821-1882) Section G-190. Author of Presbyterian Sunday School stories. Hirst, Henry Beck.(1817-1874). Section Q, Lot 225. Poet Hooper, Lucy Hamilton. Section W, Lot 17 was an assistant editor ofLippincott's Magazine from the first edition until 1874. She also wrote for Appleton's Journal and the Evening Bulletin. She wrote several books of poetry and she was also a playwright. One of her plays, Helen's Inheritance, had its premiere at the Madison Square Theater in NYC. After moving to Paris in 1874, she became the "Paris correspondent" for various American newspapers. She was also a novelist, with one of her novels, Under The Tricolor, causing quite a stir. It was a thinly-veiled satire of the lives of certain expatriates who were living in Paris at the time. Kane, Elisha Kent. Section P, Lot 100. Elisha Kent Kane(1820-1857) became famous for his arctic explorations. Kane's publications include: "Experiments on Kristine with Remarks on its Applications to the Diagnosis of Pregnancy," "American Journal of Medical Sciences, n.s., 4 (1842), The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin, A Personal Narrative, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1854, and Arctic Explorations in Years 1853, '54, '55, Philadelphia: Childs and Peterson, 1856. Lea, Henry Charles.(1825-1909) Section S, Lot 49. Pro-Northern propagandist during the Civil War, Civic Reformer, and author of a classic history of the Spanish Inquisition. Sculpture by Alexander Stirling Calder. Leslie, Eliza. (1787-1858) Section6, Lot 45. Author of MissLeslie's Directions for Cookery (1851)and other cookbooks. Lippincott, Joshua B. (1831-1886)Section 9, Lot 118. Founder of the distinguished Philadelphia publishing company. Marion, John Francis. (1922-1991) Section S, Lot 118. Philadelphia historian, author, and gentlemen. Mc Michael, Morton.(1807-1879) Section H, Lot 45. Publisher of the North American, mayor of Philadelphia, and president of the Fairmount Park Commission. Neal, Joseph Clay, (1807-1847) Section P, Lot 71. Editor and humorist, best known for Charcoal Sketches in a Metropolis. Read, Thomas Buchanan. (1822-1872) Section K, Lot 206. Both poet and sculptor, Read is best remembered for his Civil War poem "Sheridan's Ride". Singerly, William. (1832-1898) Section K, Lot 235. Made fortunes in street railways, real estate, knitting mills. Published the Philadelphia Record. Townsend, George Alfred.(1841-1914) Section 9, Lot 98. One of the most important American Journalists during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Wireman, Katharine Richardson. Section 9, Lot 160. was an illustrator who studied with Howard Pyle. She worked for the magazines that Curtis Publishing produced. Wister, Owen. (1860-1938) Section J, Lot 206. Author of The Virginian. American writer whose stories helped to establish the cowboy as an archetypical, individualist hero. Wister and his predecessor James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) created the basic Western myths and themes, which were later popularized by such writers as Zane Grey and Max Brand. The Sound on the Page by Ben Yagoda (HarperCollins, $23.95). Over the course of his career, acclaimed author, teacher, and critic Ben Yagoda has uncovered one

certain truth about writing: "Style matters." Indeed, it is frequently the case that our favorite

writers entertain, move, and inspire us less by what they say than by how they say it. Most books, including Strunk and White's classic The Elements of Style, take a narrow view of style,

suggesting that the only proper one is of plainness, simplicity, and transparency. But tell that to

David Foster Wallace, Dave Eggers, Don DeLillo, and other stylistic risk takers! While not a "how-to" manual, The Sound on the Page offers practical and incisive help for writers on identifying and developing a distinctive style and voice. Drawing on interviews with more than

forty authors -- Tobias Wolff, Elmore Leonard, Michael Chabon, Cristina Garc'a, Dave Barry,

Camille Paglia, Junot D'az, Margaret Drabble, and Bill Bryson among them Yagoda discusses: Filled with insights from outstanding writers and close readings of their works, The Sound on

the Page is an essential book for all aspiring and experienced writers, as well as for readers who

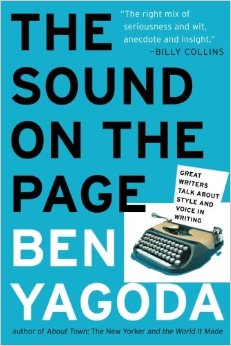

are interested in learning how their favorite writers approach the craft. Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History, 1528-1828 by Walter A. McDougall

(HarperCollins, $34.95). A powerful reinterpretation of the founding of America, by a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian

"The creation of the United States of America is the central event of the past four hundred years,"

declares Walter McDougall in his preface to Freedom Just Around the Corner. With this statement begins

McDougall's most ambitious, original, and uncompromising of histories. McDougall marshals the latest

scholarship and writes in a style redolent of passion, pathos, and humor in pursuit of truths often

obscured in books burdened with political slants. From the origins of English expansion under Henry VIII to the founding of the United States to the

rollicking election of President Andrew Jackson, McDougall rescues from myth or oblivion the brave,

brilliant, and flawed people who made America great: women and men, native-born and immigrant; German,

Latin, African, and British; as well as farmers, engineers, planters, merchants; Protestants, Freemasons,

Catholics, and Jews; and -- last but not least -- the American scofflaws, speculators, rogues,

and demagogues. With an insightful approach to the nearly 250 years spanning America's beginnings, McDougall offers his readers an understanding of the uniqueness of the "American character" and how it has shaped the wide-ranging course of historical events. McDougall explains that Americans have always been in a

unique position of enjoying "more opportunity to pursue their ambitions...than any other people in history."

Throughout Freedom Just Around the Corner the character of the American people shines, a character built out of freedom to indulge in the whole panoply of human behavior. The genius behind the success of the

The United States is founded on the complex, irrepressible American spirit. A grand narrative rich with new details and insights about colonial and early national history,

Freedom Just Around the Corner is the first installment of a trilogy that will eventually bring the

story of America up to the present day -- a story as epic, bemusing, and brooding as Bob Dylan's "Jokerman,"

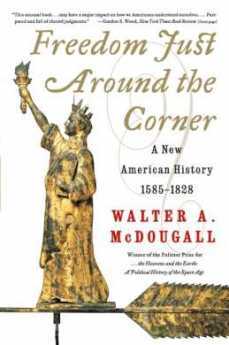

the ballad that inspires its titles. All I Did Was Ask by Terry Gross (Hyperion, $24.95). A fascinating collection of revealing and entertaining interviews by the award-winning host of National

Public Radio's premier interview program Fresh Air. Over the last twenty years, Terry Gross has interviewed many of our most celebrated writers, actors,

musicians, comics, and visual artists. Her show, Fresh Air with Terry Gross, a weekday magazine of contemporary arts and issues produced by WHYY in Philadelphia, is one of National Public Radio's most popular programs. More than four million people tune in to the show, which is broadcast on over

400 NPR stations across the country. Gross is known for her thoughtful, probing interviewing style. In her trusted company, even the most reticent guest relaxes and opens up. But Gross doesn't shy away from controversy, and her questions can be tough -- too tough, apparently, for Bill O'Reilly, who abruptly terminated his conversation with her. Her interview with Gene Simmons of Kiss, which is included in the book, prompted Entertainment

Weekly to name Simmons its male "Crackpot of the Year." For All I Did Was Ask, Gross has selected more than three dozen of her best interviews -- ones of lasting relevance that are as lively on the page as they were on the air. Each is preceded by a personal

introduction in which she reveals why a particular guest was on the show and the thinking behind some

of her questions. And in an introductory chapter, the normally self-effacing Gross does something you're

unlikely ever to hear her do on Fresh Air -- she discusses her approach to interviewing, revealing a thing

or two about herself in the bargain. The collection focuses on luminaries from the art and entertainment world, including actors,

comedians, writers, visual artists, and musicians, such as: Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German-American Identity By Russell A. Kazal (Princeton, $35). More Americans trace their ancestry to Germany than to any other country. Arguably, German Americans form America's largest ethnic group. Yet they have a remarkably low profile today, reflecting a dramatic,

twentieth-century retreat from German-American identity. In this age of multiculturalism, why have German

Americans have gone into ethnic eclipse--and where have they ended up? Becoming Old Stock represents the first in-depth exploration of that question. The book describes how German Philadelphians reinvented themselves

in the early twentieth century, especially after World War I brought a nationwide anti-German backlash. Using quantitative methods, oral history, and cultural analysis of written sources, the book explores

how, by the 1920s, many middle-class and Lutheran residents had redefined themselves in "old-stock"

terms--as "American" in opposition to southeastern European "new immigrants." It also examines

working-class and Catholic Germans, who came to share a common identity with other European immigrants,

but not with newly arrived black Southerners. Becoming Old Stock sheds light on the way German Americans used to race, American nationalism, and mass culture to fashion new identities in place of ethnic ones. It is also an important contribution to the growing literature on racial identity among European Americans. In tracing the fate of one of America's

largest ethnic groups, Becoming Old Stock challenges historians to rethink the phenomenon of ethnic

assimilation and to explore its complex relationship to American pluralism.

Human-Built World by Thomas P. Hughes (University of Chicago, $22.50). To most people, technology has been reduced to computers, consumer goods, and military weapons;

we speak of "technological progress" in terms of RAM and CD-ROMs and the flatness of our television

screens. In Human-Built World, thankfully, Thomas Hughes, a professor emeritus at Penn, restores to

technology the conceptual richness and depth it deserves by chronicling the ideas about technology

expressed by influential Western thinkers who not only understood its multifaceted character but who

also explored its creative potential. Hughes draws on an enormous range of literature, art, and architecture to explore what technology has brought to society and culture and to explain how we might begin to develop an "ecotechnology" that works with, not against, ecological systems. From the "Creator" model of development of the sixteenth century to the "big science" of the 1940s and 1950s to the architecture of Frank Gehry, Hughes nimbly

charts the myriad ways that technology has been woven into the social and cultural fabric of different

eras and the promises and problems it has offered. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, optimistically hoped

that technology could be combined with nature to create an Edenic environment; Lewis Mumford, two

centuries later, warned of the increasing mechanization of American life. Such divergent views, Hughes shows, have existed side by side, demonstrating the fundamental

the idea that "in its variety, technology is full of contradictions, laden with human folly, saved

by occasional benign deeds, and rich with unintended consequences." In Human-Built World, he offers

the highly engaging history of these contradictions, follies, and consequences, a history that resurrects

technology, rightfully, as more than gadgetry; it is in fact no less than an embodiment of human values. Three Mile Island by J. Samuel Walker (California, $24.95) Twenty-five years ago, Hollywood released The China Syndrome, featuring Jane Fonda and

Michael Douglas as a TVnews crew who witness what appears to be a serious accident at a nuclear power plant. In a spectacular coincidence, on March 28, 1979, less than two weeks after the movie came out, the worst accident in the history of commercial nuclear power in the United States occurred at Three Mile Island. For five days, the citizens of central Pennsylvania and the entire world, amid growing alarm, followed the efforts of authorities to prevent the crippled plant from spewing dangerous quantities of radiation into the environment. This book is the first comprehensive account of the causes,

context, and consequences of the Three Mile Island crisis. In gripping prose, J. Samuel Walker, the historian of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, captures the high human drama surrounding the accident, sets it in the context of the heated debate over nuclear power in the seventies, and analyzes the social, technical, and political issues it raised. His superb account of those

frightening and confusing days will clear up misconceptions held to this day about Three Mile Island. The heart of Walker's suspenseful narrative is a moment-by-moment account of the accident itself,

in which he brings to life the players who dealt with the emergency: the Nuclear Regulatory Commission,

the state of Pennsylvania, the White House, and a cast of scientists and reporters. He also looks at the

the aftermath of the accident on the surrounding area, including studies of its long-term health effects

on the population, providing a fascinating window onto the politics of nuclear power and an authoritative

the account of a critical event in recent American history. Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery and the American Revolution by David Waldstreicher (Hill & Wang, $25). Scientist, abolitionist, revolutionary: that is the Benjamin Franklin we know and celebrate. To this description, the talented young historian David Waldstreicher shows we must add runaway, slave master, and empire builder. But Runaway America does much more than revise our image of a beloved founding father. Finding slavery at the center of Franklin's life, Waldstreicher

proves it was likewise central to the Revolution, America's founding, and the very notion of freedom we

associated with both. Franklin was the sole Founding Father who was once owned by someone else and was among the few to derive his fortune from slavery. As an indentured servant, Franklin fled his master before his term was complete; as a struggling printer, he built a financial empire selling newspapers that not only advertised the goods of a slave economy (not to mention slaves) but also ran the notices that led to the recapture of runaway servants. Perhaps Waldstreicher's greatest achievement is in showing that this was not an ironic outcome but a calculated one. America's freedom, no less than Franklin's, demanded

that others forgo liberty. Through the life of Franklin, Runaway America provides an original explanation to the paradox of

American slavery and freedom.

How to Create Your Own African American Library by Dorothy L. Ferebee (Ballantine, $13.95). Here is the first book ever written to help African Americans build a home library that celebrates the diversity of their culture and heritage. How to Create Your Own African American Library truly

does unlock the door to knowledge and power. With warm and expert commentary, experienced book reviewer and avid reader Dorothy Ferebee reviews and recommends books that will help you to build your own home library. Inside you'll discover: Plus books on Travel, Music, Poetry, and Special Collections! Here's all you need to know to create a mini-university in your own home, one that is open

every day to support the highest aspirations of yourself, your children, and their children. Boardwalk of Dreams by Bryant Simon (Oxford, $35). No one can deny that casinos have brought money and crowds back to Atlantic City. Since the first casino

opened in 1978, gambling corporations have invested six billion dollars in the old resort town

and, during the 1990s, more tourists visited Atlantic City than any other place in the United States

including Las Vegas and Disneyworld. Perhaps the finest book ever written about Atlantic City,

The complete review of this book by a Temple University scholar is available on Amazon.com at the

link above. Wilt by Robert Cherry (Triumph, $24.95). Authoritative, informative, and entertaining, Wilt is the first standard biography about this

American legend the unique and unforgettable Wilt Chamberlain. One of the 20th century's greatest and most controversial athletes, Wilt also had an intensely private side that the author uncovers through years of interviews with the people closest to Wilt up until the time of his death in 1999.

This groundbreaking work successfully captures Wilt Chamberlain the man, while also closely examining