2 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Philadelphia's Archepelago of Colleges

New England had a much more religious founding culture,

Academia in the Philadelphia Region

Higher education is a source of pride, progress, and aggravation.

Although New England and Virginia were colonized fifty years before Philadelphia, the earlier American colleges were created to train ministers. The Quaker churches of Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey had no ministers, of course, and the concept that everyone ought to be a minister led the three Quaker colonies of the Delaware Bay to universal lay education sooner than those who were thinking of ministers as an elite. It also led to troubled questioning about education: what's the purpose of all this, anyway? To some extent, that's the farmer mentality showing through, although it shows up in a different light when you reflect upon the pervasiveness of Quaker education. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting still has fifty-five private schools and three highly selective colleges under its care. That's pretty remarkable for a church of only ten thousand members, competing with tax-favored education. The main exception to the religious centrality of higher education was the University of Pennsylvania, founded by the deist Benjamin Franklin. Even there, a perceived need to concentrate secular activities in one unusual college dramatizes the pervasiveness of religion in Colonial society.

The Quaker colonies -- Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey -- currently contain about 350 colleges and universities of varying size and focus, with roughly a million students in attendance at all times, and a growing number of local students studying abroad, taking a year off or deferring further education for some other reason. Southeast Pennsylvania is also distinctive in its concentration of graduate and professional schools within metropolitan Philadelphia, with a large number of free-standing liberal arts colleges feeding students inward from several hundred miles around. If these friendly neighboring undergraduate colleges are taken into account, the Philadelphia influence seems considerably greater and its apparent insularity easier to accept. Only Princeton stands aloof from this interwoven community, although the University of Pennsylvania, the central pivot, is starting to stand aside from it. The neighboring schools are slowly developing a greater affection for the city than for its largest university, which unfortunately has allowed itself to become their largest competitor rather than their leader. It's interesting to speculate what will happen if Penn fortuitously gets several big bequests, placed in the hands of a President from Elsewhere who overvalues faculty prestige and undervalues student education, the unfortunate general hallmark of the Ivy League. The invisible archipelago of semi-affiliated colleges would then probably rearrange itself around a different graduate school focus, since grievances tend to last longer than gratitude.

The anxieties and competitive recriminations of the whole college admission process are clearly asserting that America has too few pre-eminent universities and must quickly upgrade some from the ranks of the second and third prestige tiers. The nation now has thirty dominant universities (self-described as "research universities"), and apparently needs to reach three hundred to satisfy approaching student and industry demand. The analysis suggests the Philadelphia region now has two of them, needs twenty. The only reason to question this conclusion is concern that the scramble for entrance might be more related to credentials than educational need. That is, colleges have translated SAT scores into entrance tranches, so that embarrassment about asking someone his SAT score is eased by asking what college accepted him, now essentially the same question. One worries that the day after any student takes that multiple-choice test, his thirst for education can be dispensed with.

Others worry about this, too. I am familiar with one chemical engineer who has offered to fund a hundred-million dollar effort to induce more Americans to study chemistry. Like others, he is alarmed by the universal dominance of foreign students, mostly Asian, in our university science programs. If we let that continue in a science-based society, our grandchildren will be working for their grandchildren.

A third concern for the future of academia is the degree to which distorted capital expansion has been funded by government spending, especially medical spending. That may seem a peculiar viewpoint for a physician to hold, but just ask what will happen when we cure three more major diseases, such as cancer, Alzheimers, and schizophrenia. That will materially reduce the need for medical care among young adults, and prolong life expectancy among the elderly to the point where Congress will rebel at the cost of medical research, at present an unthinkable idea. Since for example Penn's medical school consumes 75% of its budget, you can imagine what convulsions lie ahead, and more easily understand the resentments lurking in colleges without medical schools. The next time a university president announces plans for a new medical school, someone should rise from the audience and ask whether that decision had been prompted by eagerness for indirect overhead allowances. And if so, how permanently the president thinks that is likely to be forthcoming.

Future Directions for Colleges

|

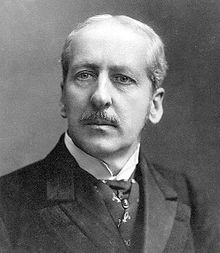

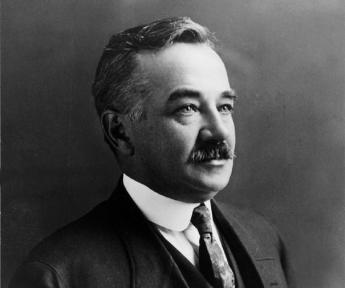

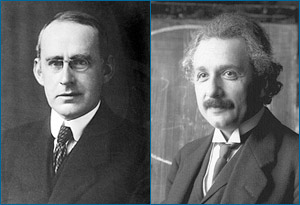

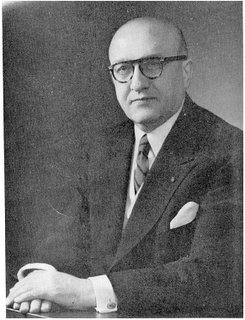

| Nicholas Murray Butler |

As Columbia University's president for forty-two years, Nicholas Murray Butler officiated at many graduation exercises in front of Columbia's Low Library. In later years, it became a prevailing joke among snickering undergraduates that he would inevitably make reference in his commencement address to the Library behind him, repeating his firm opinion that "A University is a collection of books".

|

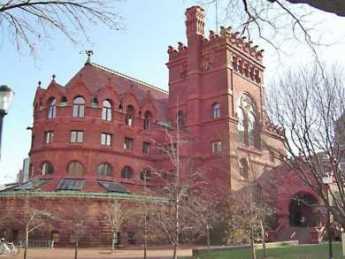

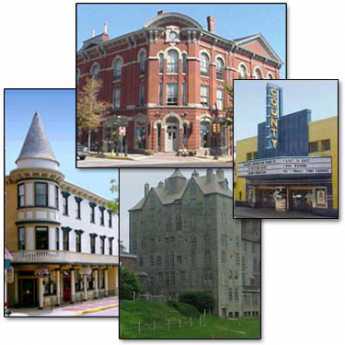

| Columbia University |

There are other opinions about what universities are, but Butler's famous oration that its library is the heart and soul of any university, is certainly defensible. It's thus plausible for what is happening to libraries to be the text here for what is currently happening to colleges. Librarians following best practices of their profession are engaged in a massive exercise in book-trading with each other, rather like the frenzied teen-age trading of postage stamps and baseball cards. Those books they have but don't much use, are traded off in return for books needed to complete a distinguished collection in whatever topic has been designated their "core mission". With efficient trading, a physical concentration of a thousand books on one topic is more valuable than the same thousand books scattered around the world and far more valuable than a thousand-book assortment of mixed messages collected in one place, which is how each library begins. Thus, having collected a higher assessment value, and a "distinguished collection" reputation, they are ready to face the threats to librarian existence from the Internet. For convenience if for no better reason, scholars in any particular topic start to congregate at a college which has a complete collection of books in their area of interest. In itself, this congregation of like-minded becomes a further attraction to other scholars. Ultimately, with a strong faculty in a particular topic, students with an interest in a career along such lines are attracted to specific colleges and become eligible to become graduate students and eventually teachers. Hidden in here somewhere is a means to advance many careers, and let's face it, to enhance faculty salaries. But it's sort of harmless, designed for the good of educational attainment and the intellectual enrichment of the nation.

Since about a quarter of a million students are constantly attending college in the general region of Philadelphia, several hundred institutions around here are continuously sorting themselves out in a gigantic archipelago of college libraries, each linked to variable football success and endowment size, specialized interests, and levels of talent. By the monograms on their sweatshirts, ye shall know them.

It surely goes too far to blame all this on Nick Butler, or a national conspiracy of librarians. We are engaged in a massive national effort to expand the excellence of our colleges and universities, to meet the transformation of our society from the industrial to the information society, and to maintain our leadership among developed nations. Fifty years ago, the Economist tells us, only three American universities could compete with Oxford and Cambridge; nowadays, at least thirty are better than anything in Europe. Judging from the present vicious scramble for admission to prestige colleges, the market could immediately absorb fifty more premiers, highly selective, world-beating universities. So, say a thousand college presidents, why not us?

In my opinion, you can see here a main underlying justification for college tuitions of fifty thousand dollars a year, per student. The individual parents say they can't afford such tuitions, and so the nation as a whole may possibly not be able to afford them, either. So far, at least, no one questions that an informal Marshall Plan for colleges is a good thing. Whenever you see a situation universally accepted like that, look out. What everybody knows, is often not worth knowing.

Among other things, American education is also headed for the specialization trap. It's rapidly becoming apparent that employers undervalue a liberal education in the people they hire; it won't take those eager beavers long to figure that out when they apply to college. Here's a tip, kids: a chemical engineer can expect to make a much larger income than a chemist. The Human Resources employees of Walmart and Microsoft were not elected to shape the future of graduate education, but that's who is going to do it if we follow present trends. If it's too strong to heap blame on industry's front men, take a look at the leaders of industry; it's rather easy to assess the academic credentials of, say, the board of directors of any local country club for their ability to shape academic policies. Whoever is making educational policy, let's restrain the growing dominance of pre-employment training in our national goals for a liberal education. Maybe it wasn't so bad when clergymen were in charge of colleges.

Other internal trends collide with external vocational pressure on colleges. The committee chose to select the concentration areas for a college library soon notice that it is easier to become notable for a rare and obscure subject than an important recognized one. Will, that leads to a desirable outcome? Everyone has a dozen editions of Shakespeare, and you can be very certain that Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard and Yale all have distinguished collections of Elizabethan literature, associated with famous scholars. Why in the world would a small struggling college try to collect Shakespeare books or Shakespeare experts? Furthermore, it is probably possible to buy a tape recording of the most distinguished Shakespeare scholar in the world, giving a breath-taking lecture on the second Act in Hamlet. Could the new Assistant Professor of Literature in a small college compete with that tape recording? On the other hand, should our most struggling colleges specialize in minor obscurities?

In fact, anything the small college teacher could say would seem shabby by comparison with the world-acknowledged master of the subject, holding forth with the lecture that made him famous. And so, one wonders, whether the current fashion to sneer at the Canon of books, written by "dead, old, white men" is not a way of avoiding comparison with performances that have survived the much hotter competition. If you carry this a little further, you can see a pressure to avoid offering courses in subject areas which centuries of serious consideration have designated to be the best that civilization offers. The top of the cultural heap has risen to the top because many generations have found what deserves to be there; one would normally suppose those topics, those authors, would be the ones you would want to study if you yourself aspire to be considered an educated person. But if present trends continue very much further, you may find that colleges which have decided to specialize in minutiae are in addition avoiding exposure of the students to what our culture considers to be the best. This is one of those things where a little is probably pretty good, but too much of it is destructive. A well-financed, highly talented college applicant can go to a place where the best of our educational product is presented in an outstanding way. Less competitive student applicants may be faced with a choice between bizarre topics, taught very well, or outstanding subjects taught rather poorly. Or, perhaps worst of all, forced to drop down to a lower rung of the academic ladder, where teaching aspirations are low in every topic so only Shakespeare, Dante, Plato, Dickens and the like can overcome deficiencies in the way they are taught.

A quick look at the other end of the spectrum gives the same thought a different twist. The universities which can afford to be insanely selective of their entering student class can also afford to ignore them. Intensely motivated, supremely talented kids, will surely succeed no matter how poorly their courses are taught. They will work hard, mainly to compete with their classmates, who are just as competitive as they are. In fact, it is surely already true that the peer pressure from their classmates has a stronger direct influence on their achievements than the faculty does. Perhaps the faculty has a strong influence indirectly, just as the president of the University is a role model five times removed. If we do not somehow reconsider the processes now underway, the archipelago of colleges will become little more than a postal sorting machine, doing its best to avoid leaving many imprints on the envelopes except a score. As the CEO of America's largest investment banking firm once told the people doing his hiring for him, "Harvard, Yale, Princeton -- Princeton preferred --, 3.6 or better. We don't care what they majored in." With a little more sophistication, displaying just a little more insight into the process, he might have added, "But make certain that what they majored in, was rigorous." If it ever gets to the point where the label you wear is more important than the training you received, the power of universities to set their own prices, select their own customers, and define their own product will have come to the end of the trail. Judging by other industries, that time will probably occur when America finally succeeds in building more first-class university campuses than we can use.

Colleges and Religions Drift Apart

|

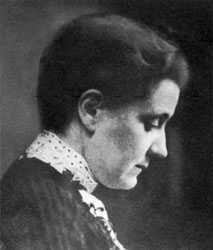

| Yale Divinity School |

Until fairly recently, academic institutions have existed as an outgrowth of religion, sort of enlarged monasteries charged with acting in loco parentis. The Catholic Church in Europe had its medieval universities, but could probably have got along without them. It was Protestantism, especially American Protestantism, which needed a place to train ministers. Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, Princeton and the other early American colleges were established to train ministers. If there was room, they sometimes took students with no intention of entering the ministry; more often, the non-ministers had enrolled with a religious vocation but drifted away from it. In time, the professional schools of medicine and law joined theology as learned professions, and of course, the colleges needed a supply of educated teachers for themselves.

And so it evolved that colleges and universities of the Philadelphia region almost always had religious sponsors, sometimes rather remotely connected, and among Catholics, the different Orders had their own colleges. Temple had Baptist origins, Princeton was Presbyterian, Eastern University was originally Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary. There is Moravian College, and so on. Since this was once an entirely Quaker region, we have Bryn Mawr College, Haverford College, and Swarthmore, although the Quakers were slow to trust the idea of colleges, since they hoped their members would remain unmoved by clergymen. The other dominant religion of the colonies, the Anglicans, split off from the British church as Episcopalians and then got somewhat scattered by the awkwardness that many Anglicans were Tories. The non-Tory Anglicans tended to wander off into Methodism, a form of Episcopalianism formed by non-ordained leaders cut off from British influences by the Revolution. The Presbyterians, however, were the heart of the American Revolution; their Scotch-Irish ancestors had no trouble saying what they thought of the British. With the attainment of Independence, they prospered as victors. Gradually, the original idea of a college to train ministers evolved into a college to teach future lay leaders of religious groups about their faith. Hidden in this transformation of the schools was an acknowledgment that leadership was migrating away from the clergy. Even the Atlantic Seaboard Quakers, who always declared they had no truck with clergy and had no fixed doctrine to teach, grasped the central point of this and formed their three colleges so that Quaker children could acquire a Quaker education, and presumably, find other Quakers to marry. That was the slogan of the times, but the underlying realization was that the enduring values of religion are guarded and promoted by an educated elite, not an ordained clergy.

This drift toward what is called secularism had some peculiarly Philadelphia variants. The University of Pennsylvania was founded by Benjamin Franklin, a deist, and has never had a divinity school, although it has a school of religious studies. A deist is someone who believes that something called God may have created the world and established its rules. Perhaps so, but since that original and final act of creation, God has simply left the world to run along on its own. Out of this arms-length piety and the dissensions of the Revolution, grew up the tradition of wealthy Philadelphia families sending their children to Harvard and Yale if Episcopalian, and to Princeton if Presbyterian. Princeton was a natural direction to take during the 19th Century when wealthy estates occupied the banks of the Delaware River all the way up to within walking distance of Princeton, and the River was the main highway. This hurt Ivy League University of Pennsylvania by draining off sources of support, either toward other Ivy League schools or to the trio of Quaker colleges. It particularly hurt Penn's undergraduate college, since the Quaker Colleges, and Princeton, held back from forming professional and graduate schools, and looked to send their graduates to Penn after the formative undergraduate years. Dickinson, Franklin and Marshall, Ursinus, Muhlenberg, and Lafayette did the same, remaining content to provide a sound liberal education rather than training for a career. Consequently, an opportunity was created for free-standing graduate schools without an undergraduate base, like Hahnemann, Women's and Jefferson Medical Colleges, or Lehigh and Drexel for engineering,, Moore School for Art. Mergers and academic imperialism have tended to push all of these free-standing units toward fuller university status. All in all, nearly a quarter of a million students now attend colleges in the Philadelphia region, and almost a million in the broad exurban area, depending on what you call a college. But a sound liberal and practical education has long ceased to be the same as a sound religious one.

Meanwhile, religion has lost its dominance in American life. Things reached some sort of climax in 2000 when Yale University officials contemplated closing the Yale Divinity School. It was said to be an expensive distraction, out of the mainstream of University life. Momentarily forgetting that the teaching of Divinity was the main reason for founding the University, those former flower children of the sixties, now fortified with tenured rank, abruptly learned that religious feeling in America is not entirely dead. Dying, perhaps, but not so dead as to forget the legalities of restricted endowment funds.

The next step in this evolution is not so clear. In 2006, while the majority of older colleges may be concentrated in "blue" states, the majority of Americans nevertheless live in "red" states, where religion is both strong and actively displeased with ceding spiritual leadership to secular universities. The decisive outcome becomes whether this topic is deemed mainly educational (decided by professors), or mainly religious (decided by clergy). At the moment it is not decisively either one.

Financing a Research University

|

| Harvard |

Fifty years ago, only three American universities, Harvard, Yale and Princeton, were considered world-class. The benchmarks for them were Oxford and Cambridge Universities; both British universities had long history and great prestige. Making allowance for wartime disruption, it was also considered pretty classy to study at the Sorbonne, or Humboldt University in Berlin. Sweden, Vienna, Rome were right up there in prestige.

|

| Oxford |

By 2004, a London magazine was offering its view there were thirty American Universities better than anything in the European Community, in particular, Oxford and Cambridge. We'll pass over the Economist's anguished analysis of what's wrong in old Europe, and focus here on what American universities are doing right. They certainly do seem to be doing something right, but nevertheless, it's still possible to be uneasy about where they are going.

|

| Cambridge |

For example, the top three all have more than ten billion dollars apiece in their endowment funds, and thus each perpetually generates roughly half a billion annually in disposable income from passive sources. You can accomplish a lot of worthwhile academic things with that much money. Operating revenue like student tuition, fees, research grants, and royalties should support normal running expenses, so endowment income is available for new frontiers of learning, research, and social endeavor. These well-run institutions unquestionably do accomplish many innovative and important advances, to the point where it is simply trivial to point out a few areas of waste or misjudgment. Multiplying their annual discretionary funds by thirty offers an overwhelming force for good in the nation, and in the world.

|

| British |

The other twenty-seven premier research universities may not all have ten billion dollars apiece, but they have the Avis or we-try-harder motivation that may make up for it. The nation really does appreciate its worth. Applications for admission outnumber available places twenty to one, would be even greater if more people thought they had a chance to get in. Outstanding professors are in scant supply, commanding higher and higher salaries. In fact, a patient of mine who is a trust and estate lawyer tells me he gets a little uneasy about the growing number of university professors he sees with million dollar estates. A calm view would be that the nation recognizes the value of superior education, and is forcing the pace for a greater supply of it. Unless our economy experiences a disastrous decline, it is reasonable to expect a hundred universities to migrate up the quality chain in the next generation; most of those eligible for it are grimly determined to see it happen. China can make all the widgets it pleases, but that won't make them catch up with this champion competitor. The French can maybe make better wine, but unless they pep up their schools, they're going to have no shot at glory.

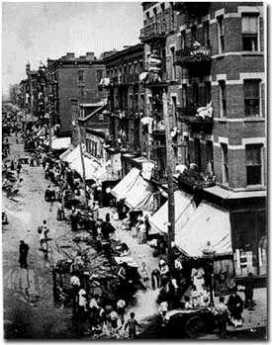

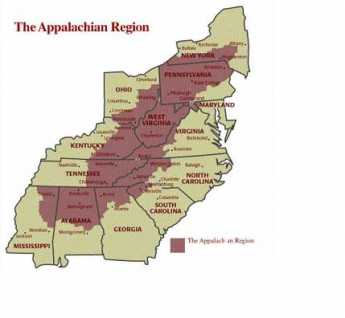

Whew. That's intentionally laying it on thick because American academic triumphalism has a darker side to give one pause. In the first place, the arrogance of it shows. Even the European aristocrats, formerly world experts in flaunted put-downs, are irritated; and red America is really sore at blue America. Sprinkling a few research universities into Arkansas and Idaho might relieve regional divisiveness somewhat, but lasting social peace can only derive from starting in the third grade of, say, North Philadelphia, Kensington, and Norristown. In economic downturns, the country would have big trouble financing universal, bottom up, academic excellence. The tragedy is that money isn't the main problem in the science classes of the thirty research universities we already have; an alarming number of those seats are filled with foreign-born students, not even to mention the honors students.

Secondly, the system is already under strain. The families of students are hard pressed by tuitions of fifty thousand dollars a year, and increasingly ready to complain about the inability, of classes of three hundred taught by non-tenured teachers, to justify to them such breath-taking fees. They may not understand educational financing, but they can count, and then multiply two numbers together. Faculty rewards favor research, not teaching, and teaching is what the students think they are paying for, their parents think they are sacrificing for. If what they are truly paying for are just credentials, they worry that affirmative action will cheapen the credentials. One clear sign of unease is the tendency of children from wealthy families to walk about the campus in torn overalls. This may be more than just a fad, it may be a sign they hope to hide from the university's system of redistributive taxation. Some people pay those high tuitions, but mostly tuitions are discounted for the eager family's ability to pay. Wearing blue jeans won't help, the universities demand to see the family's audited tax returns. In my presence, a university president remarked that the system was designed to extract the last dime from every student. The whole middle class is being asked to give until it hurts, for the unspoken goal of elevating a hundred more research universities to world class. Very few question the premise that unmatchable universities are the key to American world eminence. Quite a few, however, have anxiety that it may not work out for each individual. It may only be a lottery with slightly better odds.

Now, let's get to the research part of the research university. In the past ten years, American universities have collectively received six or seven billion in commercial patent royalties; the aggregate now runs appreciably more than a billion dollars a year and it's growing.

The normal arrangement is to give 20% of royalty income to the professor whose name is on the patent. Since most research is performed by large teams, it is possible to imagine considerable inequity and academic bad feeling in this system. In other walks of life, striving for a bigger share of two hundred million a year would cause differences of opinion about fairness. Here and there, you read articles by participants in this system who are concerned over the message it is sending to the students about personal values. Universities that began with a mission to educate the clergy are now seemingly overpraising the big payoffs.

Many business analysts feel that a successful corporation needs to spend 10% of its revenues on research and development. Behind that is a realization that prices and profit margins are largest for new inventions, steadily declining as the new invention attracts competition and eventually becomes a mere commodity. The scientific term entropy is a perfect description of the way world economies seemingly work, like clocks gradually winding down. So businessmen get rid of old products and look for new ones, and the universities are the source of most new ideas and products. Put every last cent into R & D for new products, while the developing countries grind out widgets. If we eventually graduate hundreds of thousands of Americans from unmatchably excellent research universities, the outcome will take care of itself. Even flying airplanes into our tall buildings can't make much difference in this academic arms race. It's essentially how Ronald Reagan defeated the Soviet Union, and it's discouragingly difficult to argue it is totally wrong.

However, you can imagine ways that it might all fall apart. The source of at least half the capital now pouring into the research universities comes from the federal government, particularly the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense. It only takes fifty-one votes in the U.S. Senate to change that suddenly, for reasons of national defense, to defend the value of the dollar, to combat inflation, or lots of other reasons. Even now, universities often face annual crises at the end of a funding cycle, when projects have been awarded, people hired, but funding is delayed for uncertain periods of time because of distant political wrangles within the budget process.

That's known as a cash flow problem, and even it is trivial compared with what would happen if federal research funding were delayed a full year. Just look at any university and see all the big tall buildings. They have largely been built to house research activity, and the university would have big difficulty selling them if they were empty. They've usually been paid for with mortgages, and it costs a lot of money to heat, air condition, clean and repair them. Just cut off the cash flow long enough, and you will see how risky it was to get into the research arms race.

The University City

|

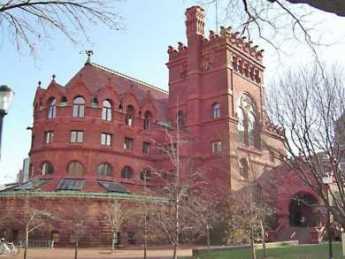

| University of Pennsylvania |

In 1920, the University of Pennsylvania graduated 34 students with B.A. degrees, and 134 with M.D. degrees. Today, the campus is a little self-contained city of 50,000 inhabitants. The transformation of the campus during that period is an outward expression of revolutionary expansion of the student body, involving demolitions, restorations, new construction. And the nearly constant shortage of parking space.

|

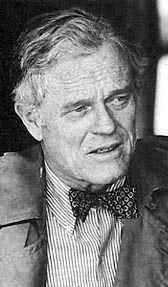

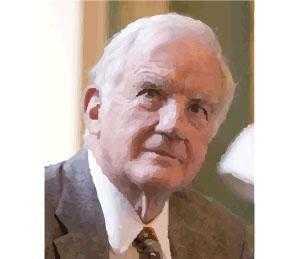

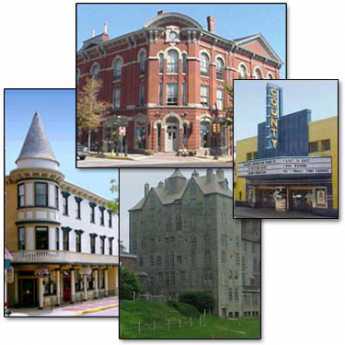

| David Hollenberg |

David Hollenberg, the University Architect, recently gave the Franklin Inn Club an interesting description of the University from the point of view of bricks and mortar. Since almost every building on the campus is undergoing or plans to undergo a major building project, he had a lot of material to cover. The disappearance of the railroad-based industrial area of West Philadelphia has been an economic problem for the city, but of course, this abundance of vacant land has created a major opportunity for the University of Pennsylvania. One reflection of this abundance is the opportunity to become the developer for much of the whole region around the campus, working with private developers who wish to be in the University area, and are therefore willing to coordinate their plans with those of the University. It's a remarkable opportunity. Since it comes at the time of a major economic downturn, one can only hope that the University does not impoverish itself taking advantage of this good luck.

|

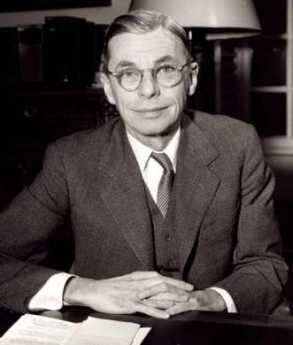

| Jonathan E. Rhoads |

As the graduation statistics illustrate, not so long ago the University was largely a medical school, with appendages. There are rumors of considerable friction from time to time, between the President of the University and the Dean of the Medical School as to who was boss; it is easy to imagine the trustees swinging from one side to the other. The most notable Provost of the University in modern times was Jonathan Rhoads, who also happened to be Professor of Surgery. If you know Quakers, you know that disputes were seldom rancorous. And if you know Jonathan, you know he almost always won the disputes.

|

| Cira Center |

While today, the dominant change is caused by the Cira Center buildings and the acquisition of the former Post Office building, it is well to keep in mind that the new Cancer Center is a billion-dollar project. A great deal of the medical school expansion is centered on burgeoning research, particularly in molecular biology, largely financed by the National Institutes of Health. While the leaders of the NIH have long struggled with Congress to keep politics out of both the administration and the substance of research, it seems to old-timers that the politicians are slowly winning. Senator Specter's seniority on the Appropriations Committee may have had as much to do with the prosperity of West Philadelphia, as the quality of research, however eminent. We are about to find out, and if things go hard with us in favor of say Chicago, it could be a wrenching experience. Most of those research buildings cost more to heat, air-condition, insure and clean than the entire tuition base of the students; and they wouldn't be good for much if you tried to sell them.

The University is almost unique in being located on contiguous land, near existing public transportation, and occupying substantial old structures capable of renovation to new purposes. Mr. Hollenberg was asked whether it was cheaper to grow like this within a city, or whether it is cheaper to plant a totally new university in several open corn fields, as we often see happen. While this is a hard question to answer, and depends to some extent on the type of architect in charge, it is his view that big-city restoration is a considerably cheaper way to expand than building from scratch on open land, although if you are starting the institution itself from scratch, there isn't much choice but the cornfield.

And then, there is the ancient argument between academics and bricks and mortar. Development officers agree that it is easier to raise donations when you can name a building for the donor; grand visions for new frontiers of teaching are a much harder sell. So a question does hang over this expansion, however exciting, whether the endowment will keep up with the structures, once the excitement of physical expansion dies down. These are definitely things to worry about, but right now you seize the opportunities as they go past, leaving integration to your successors to figure out.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Paying for College I

It's almost two platitudes that during the Nineteenth century America changed from a largely agricultural nation into a largely industrial one. And toward the end of the Twentieth century, we are going on from an industrial economy toward a service economy. This latest shift of direction is one of the main causes of soaring college tuition costs. Demand for first-class college education grows faster than price increases, competition, and internal efficiencies can seemingly control.

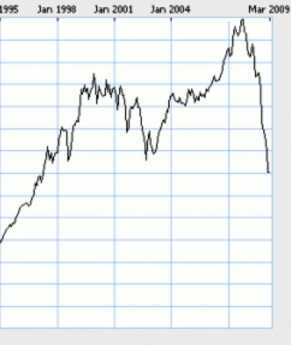

|

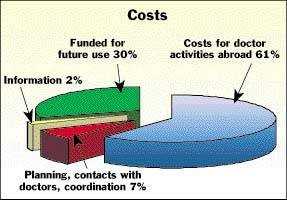

| College Cost |

Tuition costs at the top of the educational pecking order have now reached $52,000 annually, with room and board and other costs sometimes adding another fifteen thousand. Attending college already costs well in excess of the average after-tax income of working Americans, perhaps even in excess of the average income of college graduates. College costs regularly exceed the disposable income of undergraduates' parents and must be temporarily subsidized while the nation collects its wits, but subsidy cannot be a permanent solution to a problem so large. Average incomes of college graduates do exceed the average income of those who only finish high school. That extra income is gamely said to justify the investment, even taking into account the invisible loss of 4 years of earnings, perhaps even a trailing six-figure indebtedness. However, a meaningful score can only be toted up in retrospect, after inflation and taxes work their way into a net-net appraisal. Faith in some postulated answer to this accounting puzzle colors various belief systems, like: How much should we worry about widening income gaps between any income segments? What is the particular value to society of income redistribution between those who pay full tuition and those who receive financial aid?. There could be legitimate questions about many other values throughout the whole system. During the Vietnam War, many uncomfortable questions were raised about the educational system, even leading to riots on college campuses. It was often implied that many students were in college merely to escape the military draft. While that may have been precisely what was in many minds, the scramble for elite college admissions has intensified since the end of the draft, seemingly proving a college education has other merits. Steadily rising tuition costs are rapidly narrowing the income advantage, so one supposes the intrinsic merits of higher education can soon be measured by whatever enthusiasm for admission survives the bursar's bite. There are a few reasons for doubt, many reasons for anxiety.

In the first place, undergraduate tuition charges are poorly related to underlying instructional costs. It is natural to expect some markup for any product on sale, and some cushion for the unexpected. However, the difference between the tuition for night school and day school is a pretty disconcerting example. Comparatively few universities offer the same undergraduate courses as night-school courses, but a number of them do. The tuition for regular undergraduate courses is about average, somewhere around $5000 per course, but the tuition for night school is around $1200 per course -- same teacher, same textbook, same exam. Without access to the accounting data, one is led to suppose the tuition for night school comes pretty close to the true instructional cost of these courses. And therefore led to the supposition that the 300% markup for undergraduates implies that undergraduates, blue jeans and all, subsidize a great deal of unrelated activity throughout the university. This sort of discovery does not enhance the image of justice in academia.

In the second place, colleges can as easily re-direct surpluses into the endowment fund as out of it. They batter the concept of donor intent in both directions, breaking the linkage of tuition to underlying costs, and the linkage of donations to needs. Ultimately universities may be defined as mere steps to a higher income for wise investors, and cannot complain if proof of adequate return is demanded. Such accountability might even be a wise precaution, based on observation of the way Great Britain has made Oxford and Cambridge dependent on government subsidy, then subsequently allowing class warfare antagonisms to degrade the government contributions. These prestigious universities are now much humbled by transforming income inequality into a mark of shame. Unless American universities are designed to follow the same path, they will be forced to choose between competing for the way businesses do, or the way churches have traditionally done. Unfortunately, there is a reason to fear which was a college president will tip, with a cash register in one hand, and a begging cup in the other.

America is almost unique in its large proportion of small liberal arts colleges. No doubt, many of them would prefer to remain as they are, but it seems attractive to encourage thirty to fifty of them to become universities. When asked the differences, one college president replied the main difference is the presence of graduate students. Judging from the competitiveness of admission, the demand for graduate students is much closer to supply than at the undergraduate level; some tuition distortion reflects an effort to increase the supply of college teachers. Income prospects after graduation are probably an influence, but since the main occupational opportunity for graduate students is to teach undergraduates, increasing the openings for college graduates in a service economy must also imply matching the increase with more people to train them. However, only a minority of university undergraduates go on to become graduate students, so creating fifty universities also rebalances the incentives to become teachers. There are observers who advocate replacing teachers colleges with universities, a proposal which necessarily collides with the present informal dual-track system. High school teachers are mainly trained in teachers colleges, while university professors are products of graduate schools. The two streams are kept carefully separate because the commotion created by mingling them would probably be considerable. Nevertheless, this may be the rate-limiting step which will have to be addressed.

Mention of secondary education must be made, however, in order to grapple with the issue of automating education. It must be obvious that one distinguished Shakespearean scholar could replace thousands of lesser teachers of the same subject by the use of video recordings of the distinguished lecturer at work, both for introductory college courses and more advanced levels in high school. True, a small handful of pure scholars needs to be segregated away from the mass of college teachers, most of whom might prove to be graduate students. Face to face interaction is essential at every level of education of course, but automation holds such huge financial promise that greater experimentation and innovation seems inevitable. The education industry needs to make much more strenuous efforts to reduce its costs through greater adaptation to information technology if only to improve its ability to teach such adaptations to entrants into other industries. Shortening the school year, wider expansion of the Junior year abroad, and employing graduate students to teach, are debatable methods for reducing the cost of education; but an enthusiastic embrace of the computer revolution must improve educational quality before other nations leave us in their dust.

And finally, caution must be mentioned. Some degree of specialized focus of college courses is inevitable; we cannot develop scientists and engineers without it. But we must not eliminate the liberal arts, carelessly calling them luxury in a busy age. To a probably excessive degree, universities have replaced religions as a secular place to examine and teach young people how to live and behave. In little more than a generation, universities have a determined (long) hairstyle and (blue jeans) dress style, sexual morals, and political belief systems, mostly in a libertarian direction. That is not why we have colleges, or at least not why students must pay a quarter of a million dollars to experience them. There is another layer of intangible value in a liberal education, perhaps only perceived by personal experience. As I look back on a great many decades, I realize that almost every important step upward in my life was unexpected, almost unwelcome. Someone came out of the blue and offered it to me. Other people were watching and judging from behind some social bush. By contrast, almost every advancement that was strived for mightily, perhaps even a little too competitively, was to some degree gratuitously thwarted by others, often quite openly. Unobserved headhunters are watching for many qualities, particularly the ability to play this game. Spending some extended time learning what our society is all about through liberal education is a technique for self-advancement, too; universities would impair their customers' main chances in life by disturbing it.

Paying For College - II

|

| The Cosmos Club Washington D.C. |

To begin with an anecdote, I belong to a Philadelphia club which reciprocates with the Cosmos Club in Washington DC. It's a handy place to stay overnight on the rather infrequent occasion of visits to Washington on business. It happened I had an early breakfast at the Cosmos and was the only guest in the dining room. A pleasant well-dressed man came in and asked if I minded if we sat together. "I'm Bob Goheen. I work at Princeton." Since he was widely known as the President of Princeton University, he was indeed welcome. He could hardly be expected to know my daughter was then a sophomore at his college, so he was, of course, unprepared for what I had to say.

|

| Empty Pockets |

After introductory pleasantries, I told him of my arithmetic problem. My daughter was taking five courses, so the family was paying ten thousand dollars a year, per course. Since most of her courses had over two hundred students in the lecture hall, the University was being paid two million dollars to teach each course. Was it possible I had got the arithmetic wrong? Mr. Goheen neither flushed nor displayed hostility, but his manner did change. Well, of course, the tuition pays for far more than direct teaching costs. It's expensive to maintain a first-class library, the University has a responsibility to help the town of Princeton with its problems, the University is proud of its very extensive scholarship program for needy students, there is research to be sponsored. Yes, said I, you have fallen into the trap I prepared for you. My complaint is that if I had donated money for those worthy causes, it would all be tax-deductible; but by having it extracted from me under the name of tuition, I was denied the tax advantage. As expected, he quickly changed the subject. And to his evident relief, I let him do so without resistance.

Since that time, I have had the opportunity to play the same game with several college presidents; not all of them have been suave about it. The only one who took me by complete surprise was the President of Lehigh University, who not only told me he agreed but added that he had made himself unpopular with his peers by promoting exactly similar ideas. There is a very serious problem, here. Somehow, the higher education industry has got to engage in some statesmanship because it is only a matter of very short time before someone proposes a government solution.

|

| National Institutes of Health |

It is possible to treat this issue as a problem of how to pay for universal college education, which would put it in a category now occupied by health care, and probably reach a political impasse for similar reasons. Or it could be treated as a problem of teasing apart the instructional costs from the research and scholarly costs. The problem to be solved, viewed from this latter direction, assumes that excellent teaching could occur, isolated from the scholarly activities, in the manner now accepted for secondary and elementary teaching. Conversely, research institutes with no teaching responsibilities are widely accepted in Europe, for instance, while in America the National Institutes of Health are their most prominent example of its workability. It can be argued that a scholar engaged in research makes a better teacher; it can also be argued that talent for teaching is not necessarily found in those with a talent for research. While it is true that some researchers are productive even in old age, for the most part, research is like poetry and sports, a young person's game. A creative scientist can usually look forward to acting as an administrator after reaching a certain age; why not instead look forward to a career in teaching? There appears to be no serious problem with this suggestion, except the nontrivial issue of relative prestige linked to ascending income. In summary, the question is whether we can afford to put another Harvard in every town of a specified size, or whether we will be forced to transform most existing colleges into enlarged high schools, as we build more of them. Obviously, that's a cheaper method, the question is whether it is a good enough product. Whatever the model to be mass produced, the overall cost would be reduced by stripping out populations who do not need so much education, and getting Google or IBM, or someone similar, to apply massive amounts of information technology to reducing the cost. In achieving universal health care, by contrast, we can reasonably foresee research reducing most of the delivery costs we now contend with, even eliminating some of the major diseases. In education for a service economy, the potentially increasing educational need is unfortunately endless.

Therefore, no matter what pattern we adopt, it must be organized to be in competitive tension with the manpower needs of the economy, rather than unmeasurable goals like becoming well rounded. If the reason we need a vastly more educated population is to supply better-educated graduates to run the economy, some kind of tension must exist between the two, or the educational establishment will ruin us with purposeless expansion, just as some elements of the healthcare industry might wish to do with their services, and almost all trial lawyers unashamedly wish for in their area of expertise.

In this area of economic design, lies the answer which President Goheen should have made to me in the Cosmos Club. By asking for a massive tax deduction, I was yielding to the idea that education was always a responsibility of government, always paid for by rejiggering the tax code. In that direction lies disaster, since control of the tax code lies in the realm of politics and leads to populist solutions. We must not unbalance power relationships so that economic leaders, asking for a better-educated workforce, are not eventually confronted with crippling taxation for the betterment of bloated academia. A typical college has as many employees as students. We cannot get caught up in an unrestrained process leading to half of the population teaching the other half, except for those who have retired and receive a pension from both activities. Rather, this expensive quest for quality must be seen as the other half of the immigrant's dream, which is no longer that of average performance in an industrial economy, but rather that of excellence in a service economy.

The University Museum: Frozen in Concrete

|

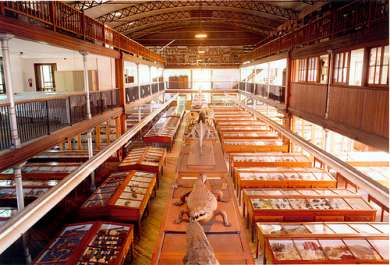

| King Tut |

Recently, a charming archeology scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, Leslie Ann Warden, entertained the Right Angle Club with the interesting history of King Tut. Interest in this subject is currently heightened by a traveling exhibit of the tomb relics currently on elegant display at the Franklin Institute. However, Philadelphia also has a permanent exhibition of Egyptian artefacts lodged in the University Museum. Since this museum is the second largest archaeology museum in the world, after the British Museum, that makes it the largest in America. An interesting sidelight is that Ms. Warden spoke in the grill room of the Racquet Club, which was the first effort by William Mercer to use "Mercer" tiles in a building. Mercer at that time was the curator of the University Museum. We learned from Ms. Warden that King Tutankhamen was unknown before his tomb was discovered, all records of this part of the Egyptian dynasty having been lost or deliberately obliterated by successors. Therefore, the discovery of these magnificent art objects started a massive expansion of scholarship about the entire Third Millenium.

|

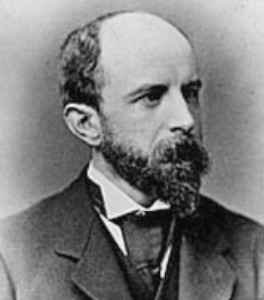

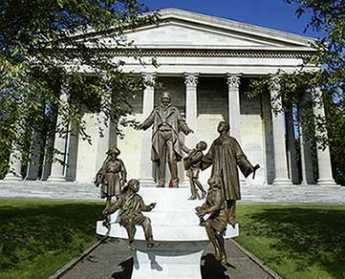

| William Pepper |

The establishment of the University Museum around 1890 was apparently mostly due to the enthusiasm of William Pepper, then Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. What seems to have got Pepper going was an expedition to Iraq, the place where civilization began, in Mesopotamia. The relics brought back from this celebrated effort needed a home, and Pepper decided it had to be here. One famous philanthropist after another, often in the role of Chairman of the Board of Trustees, carried on the tradition after Pepper's premature death. Some of them have their names on buildings, some declined. To a notable degree, the feeling of special possession was exemplified by Alexander Stirling Calder, who turned the statues in the garden to face inward rather than out toward the street. Asked whether a mistake had been made, he is said to have replied that due to the Museum's withdrawn character, it was more appropriate for the world to face the Museum. No more icily accurate comment has ever been made about the University's relation to its city neighbors.

The real knock about the Museum is that too much has been crowded into too little real estate, and the fault lies with the automobile. After the University outgrew its space at 9th and Market around 1870, moving then to West Philadelphia, the architects and the donors originally envisioned a grand boulevard of culture stretching from the South Street bridge many blocks westward. The Museum, Franklin Field, Irvine Auditorium, The University Hospital were to be the start of an imposing array of culture. Unfortunately, that was a horse-drawn conception, soon to be overwhelmed by the worst traffic jam in the city. The Schuylkill Expressway was the final blow, setting huge auto-oriented structures in place where their easy removal became difficult to imagine. The 1929 stock crash, followed by confiscatory income and estate tax rates, merely emphasized the plain fact that restoring the grand vision was beyond the ordinary aspirations of even massive private wealth. Transforming the imposing plazas of the University Museum into parking garages was probably a result of excessive despair, but if you have ever tried to find a place to park in that region you can somewhat sympathize with the small-mindedness which prompted it. Bringing back this region is going to require immense vision and resources, neither of which is exactly thrusting itself forward at present. So, unfortunately, one of the central cultural jewels of the City is buried in the midst of an impenetrable thicket of concrete and speeding automobiles, too big to move, too small to burst its bonds.

It's well worth a lot of anybody's time, and many visits. If you can find a way to get there.

Pyramid-Building, Greatly Simplified

|

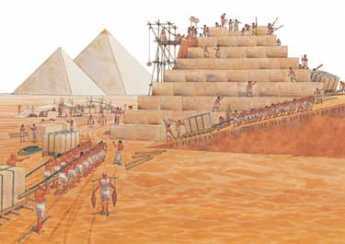

| Egyptian pyramids were supposed to be built |

Everyone who went to Sunday School knows the Egyptian pyramids were supposed to be built by huge numbers of slaves, quarrying stone blocks, transporting them with only crude rollers, and setting them precisely in place under the supervision of slave-drivers with whips. The number of stones has been estimated, a reasonable time estimate made for carving a block, and modern scholars have calculated that every single person in Eqypt must have been either a slave or a slave-driver. In fact, there is a theory among British scholars that such a mobilization of the entire nation could only have been motivated by religious fanaticism, since it's so hard to imagine keeping a nation at work involuntarily in the hot sun for twenty or more years, even with whips.

|

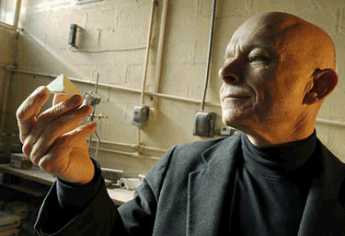

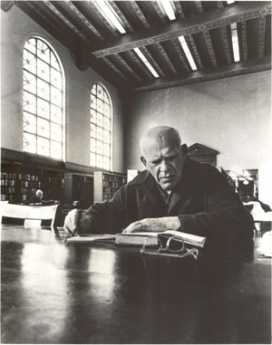

| Michael Barsoum |

As recently described to the Right Angle Club by Professor Michael Barsoum of the Ceramics Department of Drexel University, we probably have to revise our views. A "Eureka" moment seems to have first arrived for a French Professor named Joseph Davidovits several years ago, with the thought that perhaps the building blocks of the pyramids may have been cast in place rather than carved. Poured concrete, so to speak, rather than carved out of a quarry and pushed over the desert in some fashion and hauled up into place. Since the blocks seem precisely chiseled to fit together exactly, it has always been hard to imagine how this was done, when the Egyptians were thought to have no iron tools, only pure copper as a metal ingredient, not even bronze.

|

| Khufu Pyramid |

The insight was brilliant, although the evidence for it was weak, and it has been pretty easy to pick holes in the proposal. Poured concrete is much easier to reconcile with the remarkable leveling of the stone blocks, where the bottom level of the Khufu pyramid is the size of eight football fields but only varies from true level by one inch overall. Exploratory cuts into the sides of the pyramids reveal the component stones to vary enormously in size and shape in the interior, although the exterior surface is quite smooth. Similarly, the lateral sides of the pyramids vary from true north by only 1/15 of a degree, a remarkable achievement for stone cutting with primitive tools. Broad Street in Philadelphia supposedly runs North and South, for example, but it deviates from true north by six degrees. The pyramid builders, like the architects of ancient Beijing, must have used the Pole Star for orientation, rather than a magnetic compass.

|

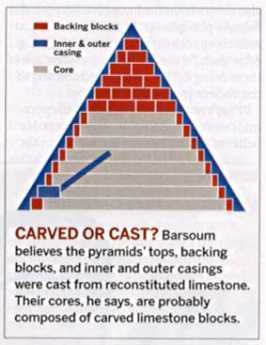

| Carved or Cast |

While Davidovits got this line of thinking started, Michael Barsoum has considerably advanced the proof of idea by addressing a large number of nitty-gritty questions about just how all this might have been accomplished. For example, the science of ceramics shifted the idea from the Portland Cement model to a recognition that the calcium in the cement came probably from diatomaceous earth, which is to say the crushed skeletons of diatoms on the ocean floor. Microscopic examination of the cement reveals large numbers of intact diatoms, with the cement layer surrounding the limestone aggregates. Furthermore, analysis of the stones shows that the outer shell of the pyramid was cast concrete, but the interior main mass was composed of stone rubble of various sizes and shapes. The apex of the pyramid was pure casting, probably because of the difficulty of fitting exterior and interior stones at the point. So, the Drexel team carried Davidiovits' idea from a general concept to a practical description of how the construction was probably accomplished. Carbon dating was attempted, but this technique stops being accurate for such remote time periods.

To nail down the idea that Philadelphia really explained how to build pyramids, funds are being collected for the construction of a 27-foot model pyramid in Logan Square. Let's hope the community gets behind this effort, which is both scholarly and entertaining, with an element of international competition mixed in. After all, Philadelphia is still smarting from the erection of the Eiffel Tower, six feet higher than Philadelphia City Hall, as the tallest structure in the world at that time. Let's be clear about it: the Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure in the world, while our City Hall remained the tallest building.

B. Franklin, Scientist

|

| Franklin Institute |

FROM time to time, the Franklin Institute has a display of its own and other museums' collections of the scientific instruments of Benjamin Franklin. It's well worth anybody's visit when it is available because the beauty and craftsmanship of these instruments alone make them remarkable works of art. Franklin was financially able to retire at the age of 42, and it tells you something of the 18th-century culture that Franklin took up scientific experiments in order to be like other independently wealthy gentlemen. Science, or natural philosophy, this seems to have been in a class with getting a coat of arms and having his portrait painted, all of which cheapens our view of Franklin as a scientist.

|

| Peter Collinson, F.R.S. |

In fact, Franklin was conducting an active correspondence with other scientists interested in electricity for many years, in particular, one Peter Collinson, F.R.S. in London. Collinson collected thirteen of Franklin's letters about his experiments, the earliest dated 1747, and printed them in 1751 as an 86-page book called Experiments and Observations about Electricity . By 1769, several more letters expanded the book to 150 pages, almost all of them describing reproducible experiments in great detail. The kite and key episode are described, but soberly and sparingly. Without making the point too graphically, an appendix was added describing how lightning had been used to kill some turkeys, so a somewhat increased power would probably be enough to kill a person. Franklin recognized that something was moving from here to there, that it had positive and negative charges, and that it was possible to store it up in a storage battery. He recognized the difference between substances that would conduct electricity and other substances that would act as insulators. Later on, he would discover that the torpedo fish stores and transmits electricity, suggesting that somehow animals made and used electricity as part of life. And of course, he put the discoveries to practical use as lightning rods, which he refused to patent.

|

| Madame Helvetius |

By the time he went to England and France as a negotiator, his wide acquaintanceship in the scientific world was happy to introduce him to other famous people, like kings, Voltaire, Mozart, and Madame Helvetius the wife of the Swiss philosopher, the only woman to whom he is known to have made a proposal of marriage. When someone mentioned standing before a king, he replied he had stood before five of them. King Louis XVI, for example, appointed Franklin to a four-man committee to investigate hypnotism, then being touted as "animal magnetism" by Franz Mesmer. The other three committee members were unfortunately also destined to become acquainted with the guillotine: Brother Joseph-Ignace Guillotin himself, and two future victims of the invention, Antoine Lavoisier the discoverer of oxygen, and Jean Sylvain Bailly who first calculated the course of Halley's Comet, not to mention Louis XVI himself. It is not easy to think of any other scientist who was able to mix his scientific fame with changing international history, acquiring in the process the sobriquet of the founder of the American diplomatic corps. But then, he was witty as well as smart, and his career is a warning to those who now hope to devote their whole lives to being admitted to a prestige college and then coasting on its reputation. Franklin, it should be remembered, dropped out of school after the second grade.

A Toast to Doctor Franklin

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Benjamin Franklin's formal education ended with the second grade, but he must now be acknowledged as one of the most erudite men of his age. He liked to be called Doctor Franklin, although he had no medical training. He was given an honorary degree of Master of Arts by Harvard and Yale, and honorary doctorates by St.Andrew and Oxford. It is unfortunate that in our day, an honorary degree has degraded to something colleges give to wealthy alumni, or visiting politicians, or some celebrity who will fill the seats at an otherwise boring commencement ceremony. In Franklin's day, an honorary degree was awarded for significant achievements. It was far more prestigious than an earned degree, which merely signified adequate preparation for potential later achievement.

And then, there is another subtlety of academic jostling. Physicians generally want to be addressed as Doctor, as a way of emphasizing that theirs is the older of the two learned professions. A good many PhDs respond by rejecting the title, as a way of sniffing they have no need to be impostors. In England, moreover, surgeons deliberately renounce the title, for reasons they will have to explain themselves. Franklin turned this credential foolishness on its head. Having gone no further than the second grade, he invented bifocal glasses. He invented the rubber catheter. He founded the first hospital in the country, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and he donated the books for it to create the first medical library in the country. Until the Civil war, that particular library was the largest medical library in America. Franklin wrote extensively about gout, the causes of lead poisoning and the origins of the common cold. By inventing bar soap, it could be claimed he saved more lives from the infectious disease than antibiotics have. It would be hard to find anyone with either an M.D. degree or a Ph.D. degree, then or now, who displayed such impressive scientific medical credentials, without earning -- any credentials at all.

Beyond Most of Us

|

| Louis I. Kahn |

The Athenaeum is slowly migrating into a national historical museum of American architecture. In this spirit, it recently presented a lecture by Carter Wiseman of Yale on the subject of Louis I. Kahn to an overflow audience. Professor Wiseman drew his remarks from his recent book about Kahn, called Beyond Time and Style.

Many giants of Philadelphia architecture, like Strickland and Walter, are known to us for the memorable public buildings they designed, but Kahn and Venturi are known for their scientific contributions to the theory of architecture. Their reputations were consequently made among architectural scholars, and then passed on to the public in the form of praise that is a little hard for laymen to understand. For example, Wiseman begins his course on Kahn by telling the students they probably will not understand Kahn at the beginning of the course, but all will revere him by the end of it. The rest of us, of course, have not attended the lectures, and a reciprocal effect probably has something to do with Kahn going to his grave, deeply in debt. No doubt the additional fact that he had three families with three women simultaneously, somewhat strained his cash flow as well.

|

| Richards laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania |

Kahn encountered the architectural field toward the end of the period of Modernism, which he referred to as "machines to live in". Rather than overturn the whole idea of Modernism, he softened its harshness through ingenious use of interior lighting, and the use of rough rather than smooth shiny materials. His teaching was that closets, elevator shafts, corridors and the like were "servant" spaces, to be hidden and subordinated to "served" spaces, like reception areas. The overall effect was a deceptive simplicity, often regarded by the public as simple boxes when the underlying design was anything but simple. For some reason, the concepts of rough surfaces and subordinated spaces was particularly effective in India and Pakistan. It was least popular in his two famous American laboratory buildings, the Richards laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. Both of these laboratories were widely praised by architects, and resoundingly hated by the chemists who used them, because chemists are particularly fond of closets. He does have one group of particular enthusiasts among those who own and inhabit the tall glass office buildings which became so popular after the Seagram's tower on Park Avenue in New York. Washing all that glass is a problem and surfaces which don't look dirty so soon, gain advantage.

Professor Wiseman spared his audience the story of Kahn's death, presumably because it is so well known. He died in the washroom of Penn Station in New York, and his body lay unidentified in the morgue for three days. It is supposed that someone stole his wallet with identification papers, because there couldn't have been much else in it to steal.

Exit, Pursued by a Bear

|

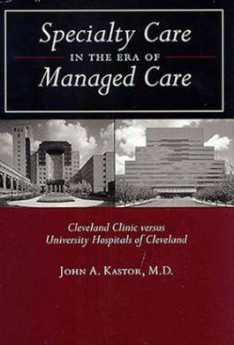

| John Kastor |

Everybody ends up getting fired in a recent book by John Kastor about recent events at the University of Pennsylvania just like everybody ending up dead in an Elizabethan play. The vital difference, of course, is that the dramatis personae at Penn can still relate to a bewildered audience their own versions of those grand events. To protect himself, the author peppers his book with more footnotes than a Ph.D. thesis. And thousands of stakeholders at the University can now realize that during those eventful times they were as clueless as Rosencranz and Guildenstern.

One basic fact about that institution is that the medical school spends three-quarters of the entire university budget. That leads to grudges in the little law school, the little engineering school, and the little president's office, as they knuckle under to the Golden Rule. The department chairman with the gold makes the rules. Since most of that gold comes from research grants, hence ultimately from the federal government, the medical students and the teaching faculty don't have the same power they had during the Vietnam War era, either. Although medical school tuition imposes a crushing burden on the students and their families, leading to debts close to a quarter of a million dollars apiece, the tuition money doesn't amount to much in the university scheme of things, either. In some schools, tuition amounts to two percent of the medical school budget. You could eliminate the students entirely and not see much difference in the "school".

Unfortunately, when you become dependent on government grants, you find they can suddenly be terminated, or awarded without funding, or held up for several months by Congressional bickering. Meanwhile, there are salaries to pay, contracts to fulfill. Even if you can furlough some of the staff, it's not easy to see what you do about a thirty-year mortgage on a research building when there is a lull in its research funding. If you try to save money, the granting agency will try to get it back; they aren't authorized to make grants to be squirreled away. If you shift money to unauthorized uses, you risk going to jail. And yet, if you don't do something along those lines, the whole enterprise can collapse.

Having said that much to be fair, it is still uncomfortable to see the financial transparency of our most valued nonprofit institutions vanish behind a Byzantine fog of secrecy, out of which arise the magnificent towers of new buildings, and in front of which an occasional limousine is to be observed. No wonder the research scientists feel the constant pressure to produce. A Nobel Prize every ten years, or so, would go a long way toward quieting envious remarks from the liberal arts faculty.

Housed in those ivy towers are three institutions, the teaching hospital, the medical school, and the university, with three boards of trustees, and at least three ruling potentates. At irregular intervals, congressional committees do things to the Budget Reconciliation Act which enrich one of the three components of the institution or suddenly impoverish another, or both. Integration of the three under one governance sounds plausible until you notice how radically different is the mission of each one. You can take a big building away from one component and rent it back to them, and things like that, but you can't do it without starting whispers about Enron. You can gather up surplus funds from one of them during the decade of the eighties, but you have trouble giving it back twenty years later. Officials at Blue Cross come snooping to see if health insurance premiums are passing through this shell game, ultimately paying salaries in the department of English Literature. Everybody distrusts everybody else, somebody sasses somebody, and everybody gets fired.

Nothing unusual about that. It happens at every medical school.

Please Don't Lose Any Sleep Over This

|

| Dr. Charles Czeisler |

The Institute for Experimental Psychiatry Research Foundation meets alternatively in Boston and Philadelphia, in recognition of its rather complicated historical relationship with Harvard and Penn. The Spring 2005 trustees meeting was held in Boston, with Dr. Charles Czeisler of the Brigham and Women's Hospital making a presentation of his work with sleepy resident physicians. Sleep is now a central focus of the work of the Institute, particularly the effect of lack of sleep on performance. Resident physicians are a group with lots of experience with sleep loss, so much that such experiences as residents are central imprinting in the lifelong brotherhood of the profession. The public tends to regard the torment of protracted craving for sleep as some kind of dangerous hazing inflicted on professional newcomers by sophomoric seniors. Every once in a while, someone gets hurt by these games. That seems to be a general public reaction. For the most part, by contrast, members of the profession who have themselves undergone the experience turn away silently from such unfeeling remarks. As the old contraceptive joke about the Pope has it, if you don't play the game, don't make the rules.

In the first place, it is wrong to suggest that resident physicians are somehow helpless victims of authority, abused slaves of somebody's profit motive, or warped masochists enduring the process in order to inflict it on someone else. Perhaps the example of my classmate Seibert is useful. As a freshman medical student, Seibert was so overwhelmed by the volume of facts he was expected to learn, that he decided to give up sleep entirely. Seibert, by the way, was no moron; he was an honors graduate of a very selective Ivy League university. And he actually did stop sleeping for more than two weeks until he collapsed and had to be stopped. This was his own choice, gamely adopted in spite of general ridicule. And to show that overachieving is not limited to physicians, there was my oriental patient, the daughter of the President of her country. She related that as a graduate student she did not go to bed for three years; during all that time, she sat at her desk, slapping her face to keep awake. What we are talking about here is a self-selected group of committed and dedicated people, perhaps overly shamed by the specter of failure.

The work of our Institute has helped document and understand the injurious effect of sleep loss on performance; no one can go very long without sleep before responses and vigilance begin to deteriorate. A great many vehicle accidents are caused by drowsy drivers; it is a concern that pilots of airplanes on long-distance flights are to some provable degree less competent to land the plane. Therefore, it is not completely surprising to find that interns on protracted duty do make 20% more errors in medication orders, and nearly 50% more diagnostic errors. It is jarring to discover a measurable increase in the number of intern auto accidents, particularly when driving home from work. Maybe we ought to pass a law about it.

Commiseration is one thing; proposals to interfere are quite another. For one thing, the time-honored protection against the harm of this problem is redundancy. The complex, fast-paced and dangerous environment of a hospital, like that of an airline cockpit, has very little tolerance for lack of vigilance. Our solution has been to do everything three times, with overlapping responsibilities and repeated opportunity for catching errors before they get through to the patient. Although the malpractice lawyer seeks to pin the whole blame on some person, particularly one who is covered by insurance, the reaction of doctors to adverse events is to presume that at least three people must have cooperated in letting it slip through. At night and on weekends, the reduced staff tends to weaken the defensive network. But by every assessment, the greatest threat to our protective screen of redundancy is cost control. Any manager of managed care can find duplication and overlap in ten minutes of searching for it in a hospital; redundancy is a big factor in the high cost of running a hospital. The law of decreasing returns will dictate that it becomes very expensive to eliminate the last one percent of errors. To state it in reverse: it is very tempting to save a bundle of money in a competitive world, by accepting only a small increase in the errors. Since it is a matter of opinion, physicians are grimly determined that it shall be physicians who strike that balance. Those who press for more punitive treatment of physicians in the matter of errors should reflect that it surely will convince physicians to flee the risk of responsibility for the decision of where to strike the balance.

If you bend metal repeatedly it will crack; if you stretch a rope too hard it will snap. These unfortunate events are not called errors, and it is improper to search for blame in them. The medical profession is aghast that the public does not seem to appreciate that average life expectancy has increased by thirty years in the past century. That's not ancient history; life expectancy has increased by three years in the past ten. A system that produces a result like that is entitled to a certain amount of tolerance for its errors if we must call them errors. In other environments, that's known as pushing the envelope. Anyone who thinks it's fun to stand on your feet for thirty-six consecutive hours -- hasn't tried it.

Surgeons are perhaps somewhat more conscious of the need to train young professionals to drive themselves beyond ordinary endurance. After all, if an operation is unexpectedly prolonged, the surgeon can't just quit, he must finish. Neurosurgeons, with their fourteen-hour procedures, are particularly vehement on the topic. But it is true of every physician, too. When the telephone rings in the middle of the night, will this young fellow haul himself out of bed, or will he tell the patient to take an aspirin and call again in the morning? Increasingly, we hear complaints from patients that other doctors didn't even take the trouble to examine them; the implication that we are somehow not like that is very flattering. Part of the training is forbearance, too. At three in the morning, it is very easy to feel sorry for yourself and to reflect that an administrator with four times your income is home in his nice warm bed. The fact is, that if the person who is up and on his feet doesn't do the job, no one will.

|

| Cadwalader |

Some incomprehension from bystanders must simply be endured with patience. Beyond that, it could be futile to seek a complete understanding. Quite recently, I was explaining to a young lady in a tailored suit who Thomas Cadwalader was. His portrait, beneath which we were standing, hangs in the great hall of the Pennsylvania Hospital. Although he died in 1789, Dr. Cadwalader is still famous for his remarkable, unfailing courtesy. A sailor in a tavern on Eighth Street once waved a gun and announced to the crowd he was going out the swinging doors to shoot the first man he met. The first man happened to be Dr. Cadwalader, who tipped his hat and said, "Good morning, sir." So, the sailor shot the second man he met.

The young lady in the tailored suit brightened up. "The moral of that story, " she said, "Is always wear a hat."

Why Are Hospital Prices So High?

|

| Aspirin |

Cost analysts maintain it really does cost ten dollars to write a simple business letter, so maybe it's no surprise when hospitals charge ten dollars to administer an aspirin tablet.