2 Volumes

The American Constitution

Ours is the first written Constitution, and the only one which has lasted two hundred years.

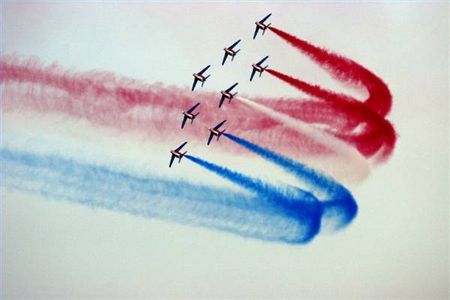

European Common Market and the American Constitution Compared

It is an interesting question how similar the constitutions of the European Union and the United States are, while reaching dissimilar outcomes. A real question arises whether further small modification might trigger major changes, or whether Constitutions are just less important than our Founding Fathers believed. If we expect different outcomes, It can be an important question.

Constitution and Civil War

The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery (and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime). It was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House on January 31, 1865.

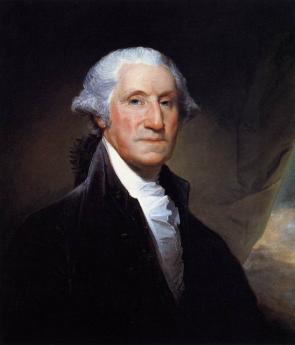

The American Constitution was written in 1789, following George Washington's view that if you are strong, others will leave you alone. Quietly in the background was Robert Morris, remembering how hard it had been to collect taxes due under the Articles of Confederation. Ever since the 1754 Albany Conference, Ben Franklin had dreamed of an English-speaking unification, and Thomas Jefferson maybe a French one. Other notions floated around but Washington and Madison avoided opposition when they could. There had to be unification, but the final test was ratification by Bill of Rights people, who primarily feared any central power at all would lead to trouble. Those who distrusted Washington feared to oppose him openly, his slave-holdings increased their hesitation.

The Civil War

War of Northern Aggression or Treason?

Jury Nullification

|

| Tom Monteverde |

We must be grateful to the late distinguished litigator, Tom Monteverde, for reminding us of the importance of the jury in American history. Juries seldom realize how much power they can have if they unite on a common purpose. In fact, juries have the implicit right to veto almost anything the rest of government does, by rendering it unenforceable. If the jury opinion is a majority view, nothing but a civil war can legally stop them. So it helped Washington to have jury nullification seem an invincible Quaker idea, while the South trusted a rich slave-owner who had renounced power.

|

| William Penn |

The right to a jury trial originated in the Magna Carta in 1215, but a jury's essentially unlimited power was established four centuries later by Quakers. The legal revolution grew out of the 1670 Hay-market case, where the defendant was William Penn, himself. Penn was accused of the awesome crime of preaching Quakerism to an unlawful assembly, and while he freely admitted his guilt he challenged the righteousness of such a law. The jury refused to convict him. The judge thus faced a defendant who said he was guilty and a jury who said he wasn't. So, the exasperated judge responded -- by putting the jury in jail without food.

The juror Edward Bushell appealed to the Court of Common Pleas, where the problem took on a new dimension. The Justices certainly didn't want juries flouting the law, but nevertheless couldn't condone a jury being punished for its verdict. Chief Justice Vaughn decided that intimidating a jury was worse than extending its powers, so the verdict of Not Guilty was upheld, and Penn was set free. Essentially, Vaughn agreed that any jury that wasn't allowed to acquit was not really a jury. In this way, the legal principle of Jury Nullification of a Law was created. A verdict of not guilty couldn't make William Penn innocent, because he pleaded guilty. A verdict of not guilty, under these circumstances, meant the law had been rejected. Jury nullification thus got to be part of English Common Law, hence ultimately part of the American judicial system.

|

| Andrew Hamilton |

This piece of common law was a pointed restatement of just who was entitled to make laws in a nation, whether or not nominally it was ruled by a king or a congress. Repeated British evasion of the principles of jury trial became an important reason the American colonists eventually went to war for independence, and probably a better one than some others. The 1735 trial of Peter Zenger was an instance where Andrew Hamilton, the original "Philadelphia Lawyer", convinced a jury that British law, blocking newspapers from criticizing public officials for improper conduct, was too outrageous to deserve enforcement in their court. In that case, jury defiance became even more likely when the judge instructed the annoyed jury that "the truth is no defense". Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette was here quick to come to the side of jury nullification, saying, "If it is not the law, it ought to be law, and will always be law wherever justice prevails." Franklin quickly became allied with Andrew Hamilton, who became Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly.

|

| John Hancock |

The Zenger case was often stated to be the origin of the Freedom of the Press in our Constitution fifty years later, but in fact the First Amendment merely provides that Congress shall pass no laws like that. Hamilton had persuaded the Zenger jury they already had the power to stop enforcement of such tyranny, and the First Amendment could be seen as trying to prevent enactment of laws that will foreseeably incite a jury to revolt.

The Navigation Acts of the British government, for example, were predictably offensive to the American colonists, whose randomly chosen representatives on juries were then rendered useless with their wide-spread refusal to convict. This, in turn, provoked the British ministry. John Adams made a particularly famous defense of John Hancock who was being punished with confiscation of his ship and a fine of triple the cargo's value. Adams was later singled out as the only named American rebel the British refused to exempt from hanging if they caught him. As everyone knows, Hancock was the first to step up and sign the Declaration of Independence, because by 1776 there was widespread colonial outrage over the British strategy of transferring cases to the (non-jury) Admiralty Court. Many colonists who privately regarded Hancock as a smuggler were roused to rebellion by the British government thus denying a defendant his right to a jury trial, especially by a jury almost certain not to convict him. To taxation without representation was added the obscenity of enforcement without due process. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the newly created United States, ruled in 1794 that "The Jury has the right to determine the law as well as the facts." And Thomas Jefferson built a whole political party on the right of common people to overturn their government, somewhat softening, it is true, when he grasped where the French Revolution was heading. Jury Nullification then lay fairly dormant for fifty years. But since the founding of the Republic and the reputation of many of the most prominent founders was based on it, there was scarcely need for any emphasis.

|

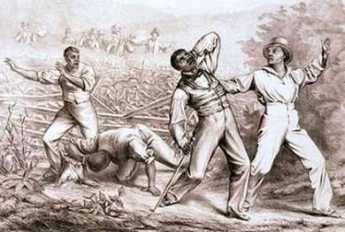

| Slave |

And then, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 began to sink in. It became evident that juries in the Northern states would routinely refuse to convict anyone under that law, or under the Dred Scott decision, or any other similar mandate of any branch of government. In effect, Northern juries threw down the gauntlet that if you wanted to preserve the right of trial by jury, you had better stop prosecuting those who flouted the Fugitive Slave law. In even broader terms, if you want to preserve a national government, you had better be cautious about strong-arming any impassioned local consensus. A rough translation of that in detail was that no filibuster, no log-rolling, no compromises, no oratory, no threats or other maneuvers in Congress were going to compel Northern juries to enforce slavery within their boundaries of control. All statutes lose some of their majesties when the congressional voting process is intensely examined, and public scrutiny of this law's passage had been particularly searching. Even if Southern congressmen would be successful in passing such laws, it wasn't going to have any effect around here. The leaders of Southern states quickly got a related message, and their own translation of it was, "We have got to declare our independence from this system of government that won't enforce its own laws". If juries can nullify, then states can nullify, and the national union was coming to an end. Both sides disagreed so strongly on this one issue they were willing, for the second time, to risk war for it.

Ku Klux Klan

The idea should be resisted that Jury Nullification is always a good thing. After the Civil War, many of the activities of the Ku Klux Klan were tolerated by sympathetic juries. Many lynch mobs of the Wild, Wild West were encouraged in the name of law and order. Prohibition of alcohol by the Volstead Act was imposed on one part of society by another, and Jury Nullification effectively endorsed rum-running, racketeering, and organized crime. The use of marijuana and abortion are two further examples where disagreement is so strong that compromise eludes us. What is at stake here is protecting the rights of a minority, within a society run by a majority. If minority belief is strong enough, jury nullification issues an unmistakable proclamation: "To proceed farther, means War."

|

| Oliver Wendell Holmes |

That's a somewhat strange outcome for a process started by pacifist Quakers, so the search goes on for a better idea. Distinguished jurists differ on whether to leave things as they are. In a famous exchange, Oliver Wendell Holmes once had dinner with Judge Learned Hand, who on parting extended a lawyer jocularity, "Do justice, Sir, do justice." To which, Holmes then made the somewhat surly response, "That is not my job. My job is to apply the law."

Thus lacking any better approach, it is hard to blame the US Supreme Court for deciding this was something best left unmentioned any more than absolutely necessary. The signal which Justice Harlan gave in the majority opinion on the 1895 Sparf case was the very narrow ruling that a case may not be appealed, solely on the basis that the trial jury was not informed of its right to nullify the law in question. Encouraged by this vague hint, what has evolved has been a growing requirement that incoming jurors take an oath "to uphold the law", officers of the court (ie lawyers)are discouraged from informing a jury of its true power to nullify laws, and Judges are required to inform the jury in their charge that they are to "take the law as the judge lays it down" (ie leave appeals to higher courts). If a jury feels so strongly that it then persists in spite of those restraints, well, you apparently can't stop them. Nobody thinks this is a perfect solution, and aggrieved defendants like the Vietnam War protesters are quite vocal in their belief that the U.S. Supreme Court finally emerged with a visibly asinine principle: a jury does indeed have the right to nullify, but only as long as that jury is unaware it has that right. That's almost an open invitation to perjury if accurate; but while it's not precisely accurate, it comes close to being substantially true.

That's where matters stand, and apparently will stand, until someone finds better arguments than those of Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Andrew Hamilton -- and William Penn.

John Marshall's Constitution

|

| Patrick Henry |

The best way to remind Americans, especially skeptical ones, of the unique value of our Constitution is to ask a question. "Can you name a single other examples in all recorded history where thirteen nations peacefully gave up sovereign power to become one unified nation?" No, but it took two hundred years of failures of similar attempts, to demonstrate the American achievement. The U.N. and the European Union are recent examples of other failed attempts to conciliate and unify; the French Revolution was an early botched one. With few exceptions, unions are unified at swords point. This dismal record exists in spite of abundant evidence that most nations are too small to prosper; it seems to be necessary to beat people over the head to make them agree to be prosperous. Even so, ratifying our unification was a close call, hotly resisted by notables like Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson.

|

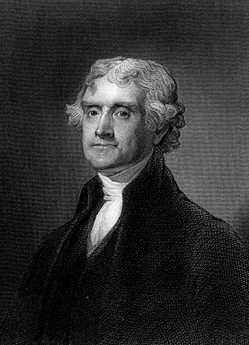

| Thomas Jefferson |

Many historians conclude our Constitution was merely lucky, could not have been accepted at any other time, except immediately following a shared revolt against high-handed misrule. During that eight-year war, the follies of ruinous inflation, unenforceable contracts, drum-head justice and inability to collect taxes -- the collective anarchies of feeble government -- were everyday observations. America wanted to rid itself of a king, but it was plain that without that remarkable man, George Washington, peace and prosperity were inconceivable. In short, America had just felt the consequences of the many choices it would need to avoid, so in 1787 we avoided them. A much-criticized decision was made by the founders to avoid the slavery issue and a good thing we did. Eighty years later we still had to fight our bloodiest war, just to hold that Union together. The industrialized North did not go to war to free slaves. It fought to preserve a dynamic Union of expanding states. Even The South was not defending slavery so much as struggling to preserve a place in this new world until it could find some plausible way to escape its antiquated life support. That is not easy to do under a system of majority rule.

Although the Constitution enshrines majority rule, the American Union is held together with the glue of decent respect for minority viewpoints. That's fragile glue, indeed. In any unavoidable collision of interests, the main argument for still leaving the Constitution untouched is not respect for Original Intent. It is fear this unique accomplishment will disintegrate if tinkered with.

|

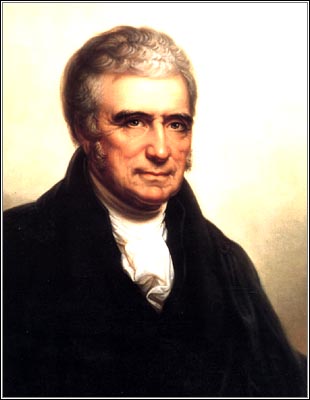

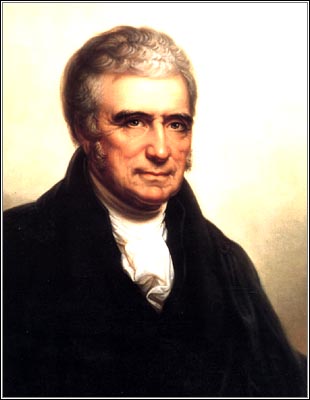

| John Marshall |

Three other introductory points need to be made, about John Marshall, about Philadelphia, and about the evolution of common law into statutory law. The Constitution we know did not emerge complete from the 1787 Convention, or even after the first Congress produced the Bill of Rights in 1791. John Marshall, who did complete it, was not even the first Chief Justice. Nevertheless, almost alone he forged national agreement on three essential points: 1. The Constitution is the keystone of our legal system, dominant over other authority. 2. Since the Republic began with a legal blank slate, English Common Law is the default position, but only until the Supreme Court rules on it or Congress asserts a statute. 3. The Supreme Court and only the Supreme Court may define what the Constitution means when challenged. These three unwritten axioms seemed so clear and irrefutable when Marshall deployed them, that they still stand -- because they are unchallengeable, not because they were ratified.

Finally, the rest of the nation may not be completely comfortable hearing a Philadelphian declare that our quite singular Constitution could not have emerged from any other city, as well as at any other time. The evidence to support what some may call chauvinism rests on the historically abrupt decline of American civic virtue as soon as the nation's capital moved to less utopian surroundings. Others may well have a different viewpoint, but the opinion remains that the nation survived the chaos from 1800 after the migration of the Capital from Philadelphia, until the end of Civil War -- only because we were protected by thousands of miles of ocean.

Joseph Story on Politics Under the Constitution

|

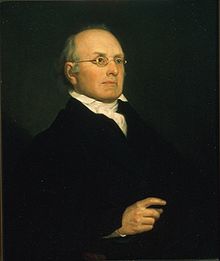

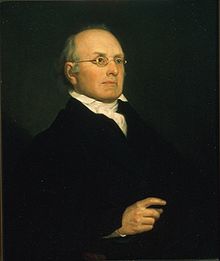

| Joseph Story |

The structure [of the Constitution] has been erected by architects of consummate skill and fidelity; its foundations are solid; its compartments are beautiful, as well as useful; its arrangements are full of wisdom and order; and its defenses are impregnable from without. It has been reared for immortality, if the work of man may justly aspire to such a title.

It may, nevertheless, perish in an hour, by the folly, or corruption, or negligence of its keepers, THE PEOPLE. Republics are created by the virtue, public spirit, and intelligence of the citizens. They fall, when the wise are banished from the public councils because they dare to be honest, and the profligate are rewarded, because they flatter the people, in order to betray them.

REFERENCES

| A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution of the United States: Containing a Brief Commentary on Every Clause, Explaining the True Nature, Reasons, and ... Designed for the Use of School Libraries and General Readers; Joseph Story: ISBN-13: 978-1886363717 | Amazon |

Aftermath: Who Won, the States or the Federal?

|

| Thirteen Sovereign States |

In the case of the American Constitution, the initial problem was to induce thirteen sovereign states to surrender their hard-won independence to a voluntary union, without excessive discord. Once the summary document was ratified by the states, designing a host of transition steps became the foremost next problem. The dominant need at that moment was to prevent a victory massacre. The new Union must not humble once-sovereign states into becoming mere minorities, as Montesquieu had predicted was the fate of Republics which grew too large. Nor must the states regret and then revoke their union as Madison feared after he had been forced to agree to so many compromises. As history unfolded, America soon endured several decades of romantic near-anarchy, followed by a Civil War, two World Wars, many economic and monetary upheavals, and eventually the unknown perils of globalization. When we finally looked around, we found our Constitution had survived two centuries, while everyone else's Republic lasted less than a decade. Some of its many flaws were anticipated by wise debate, others were only corrected when they started to cause trouble. Still, many tolerable flaws were never corrected.

Great innovations command attention to their theory, but final judgments rest on the outcome.

|

| . |

Benjamin Franklin advised we leave some of the details to later generations, but one might think there are permissible limits to vagueness. The Constitution says very little about the Presidency and the Judicial Branch, nothing at all about the Federal Reserve, or the bureaucracy which has since grown to astounding size in all three branches. Political parties, gerrymandering, and immigration. Of course, the Constitution also says nothing about health care or computers or the environment; perhaps it shouldn't. Or perhaps an unmentioned difficult topic is better than a misguided one. Gouverneur Morris, who actually edited the language of the Constitution, denounced it utterly during the War of 1812 and probably was already feeling uncomfortable when he refused to participate in The Federalist Papers . Madison's two best friends, John Randolph, and George Mason, attended the Convention but refused to sign its conclusions, as Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson almost certainly would also have done. On the other hand, Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris came to the Convention preferring a King to a President, but in time became enthusiasts for a republic. Just where John Dickinson stood, is very hard to say. Those who wrote the Constitution often showed less veneration for its theory, than subsequent generations have expressed for its results. Understanding very little of why the Constitution works, modern Americans are content that it does so, and are fiercely reluctant about changes. The European Union is now similarly inflexible about the Peace of Westphalia (1648), suggesting that innovative Constitutions may merely amount to courageous anticipations of radically changed circumstances.

|

| President Franklin Roosevelt |

One cornerstone of the Constitution illustrates the main point. After agreeing on the separation of powers, the Convention further agreed that each separated branch must be able to defend itself. In the case of the states, their power must be carefully reduced, then someone must recognize when to stop. If the states did it themselves, it would be ideal. Therefore, after removing a few powers for exclusive use by the national government, the distinctive features of neighboring states were left to competition between them. More distant states, acting in Congress but motivated to avoid decisions which might end up cramping their own style, could set the limits. The delicate balance of separated powers was severely upset in 1937 by President Franklin Roosevelt, whose Court-packing proposal was a power play to transfer control of commerce from the states to the Executive Branch. In spite of his winning a landslide electoral victory a few months earlier, Roosevelt was humiliated and severely rebuked by the overwhelming refusal of Congress to support him in this judicial matter. The proposal to permit him to add more U.S. Supreme Court justices, one by one until he achieved a majority, was never heard again.

|

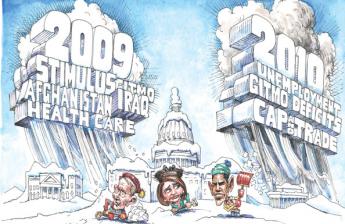

| Taxes Disproportionately |

Although some of the same issues were raised by the Obama Presidency seventy years later, other more serious issues about the regulation of interstate commerce have been slowly growing for over a century. Enforcement of rough uniformity between the states rests on the ability of citizens to move their state of residence. If a state raises its taxes disproportionately or changes its regulation to the dissatisfaction of its residents, the affected residents head toward a more benign state. However, this threat was established in a day when it required a citizen to feel so aggrieved, he might angrily sell his farm and move his family in wagons to a distant region. People who felt as strongly as that was usually motivated by feelings of religious persecution since otherwise waiting a year or two for a new election might provide a more practical remedy. However, spanning the nation by railroads in the 19th Century was followed by trucks and autos in the 20th, and then the jet airplane. While moving residence to a different state is still not a trivial decision, it is now far more easily accomplished than in the day of James Madison. A large proportion of the American population can change states in less than an hour if they must, in spite of a myriad of entanglements like driver's licenses, school enrollments, and employment contracts. The upshot of this reduction in the transportation penalty is to diminish the power of states to tax and regulate as they please. States rights are weaker since the states have less popular mandate to resist federal control. It only remains for some state grievance to become great enough to test the present power balance; we will then be able to see how far we have come.

|

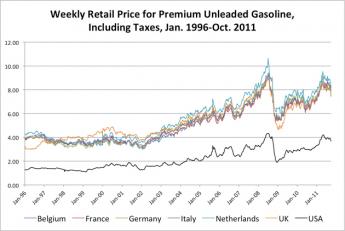

| High Gasoline Taxes of Europe |

Since it was primarily the automobile which challenged states rights and states powers, it is natural to suppose some state politicians have already pondered what to do about the auto. The extraordinarily high gasoline taxes of Europe have been explained away for a century as an effort to reduce state expenditures for highways. But they might easily be motivated by a wish to retard invading armies or to restrain import imbalances without rude diplomatic conversations. But they also might, might possibly, respond to legislative hostility to the automobile, with its unwelcome threat to hanging on to local populations, banking reserves, and political power.

It helps to remember the British colonies of North America were once a maritime coastal settlement. The thirteen original states had only recently been coastal provinces, well aware of obstructions to trade which nations impose on each other. Consequently, they could readily design effective restraints to mercantilism within the new Union. Two centuries later, repeated interstate quarrels provided fresh viewpoints on old international problems. As globalization currently becomes the central revolution in trade affairs of a changing world, America is no beginner in managing the intrigues of international commerce. Or to conciliating nation states, formerly well served by nation-state principles of the Treaty of Westphalia, but this makes them all the more reluctant to give some of them up.

Other Constitutional Issues

As Europe Learned: Common Currency Without Common Government Spells Trouble

When the Europeans decided to edge gradually into united nationhood, step by step, starting with a unified currency, Milton Friedman was immediately scornful. Mr. Friedman had won a Nobel Prize for his work in monetary matters and told the world that he didn't think the Euro would last ten years. At the end of ten years, it began to look as though he was right. Since even pirates had once been willing to accept Spanish gold coins at face value, it takes a little explaining to understand why it makes any difference whether the issuing countries of the Euro are yoked in common nationhood.

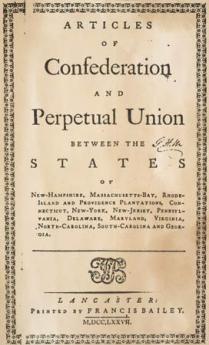

American Articles of Confederation, Valuable or Hindrance?

|

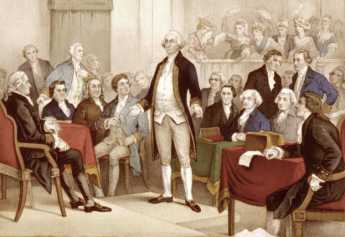

| Continental Congress |

THE British may well have been high-handed with their American colonies, but they were precise while enacting the Prohibitory Act of December 1775 about why they would attack militarily in 1776. Their American subjects had formed a rebel government in 1775 called the Continental Congress, which then dispatched an Army under George Washington to wage war against British forces in Boston; and then showed no signs of disbanding. What could you call that, except an armed mutiny?

|

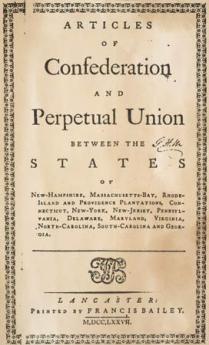

| Articles of Confederation |

The American colonists naturally had a different viewpoint. Because of the Prohibitory Act of 1775, they needed an established government of some sort to exist if war came, preferring not to be hanged for treason in defense of their rights as British subjects. Their primary grievance, at least at first, was taxation without representation. Many colonists were resistant to more than temporary independence from Britain. The most common goal of American moderates was then a variant of commonwealth similar to what was being discussed for Ireland. Once the British navy actually attacked, however, a strategic document describing what was contemplated for the far future was counter-productive. Strategic discussion bogged down into meaningless disputes between conservatives who wanted a strong central government, and radicals who argued for states' rights, neither of which was sufficiently tactical with British soldiers marauding the land.

To repeat the default position: Fighting the British fleet off Staten Island risked immediate hanging from the yardarm for treason, and the Articles of Confederation served the immediate purpose of legitimizing that. Lawyers may sometimes get lost in their own reasoning, but in this case, the advice was sound. Reconsidering the Articles after the Treaty of Paris was more appropriate, a smokescreen now only useful for confusing an angry British Admiral.

Although John Dickinson produced a workmanlike document in 1777 called the Articles of Confederation, it was weakened and not closely followed; formal ratification drifted during the first four years of the war. The chaotic situation also provided a pretext for some of the colonies to contribute less money or troops than their representatives promised. However, after five years of bloody warfare, an unratified Constitution became increasingly hard to justify, its disadvantages eventually outweighing any argument in favor. Robert Morris also decided the Articles needed to be ratified, as a sign of sufficient unity to justify long-term loans to them.

|

| Robert Morris |

Morris at that time was called the Financier, a poorly defined office which in his aggressive hands meant Morris was effectively running the country. His position put him in the center of unenforceable promises of aid from the thirteen states, justified to him in all the contradictory ways of beleaguered debtors. Morris was enough of a businessman to know that hard-pressed debtors frequently offer weak excuses. So, whether he felt he was thwarting phony evasions, or really believed the states had legal concerns, he pressed ahead vigorously for ratification of the Articles of Confederation. This was soon accomplished in 1781, but unfortunately, it made little difference. It can be safely surmised this experience hardened his long-expressed conviction that every federal government must at a minimum have realistic power to collect taxes to service its debts. But to accomplish that, now required those ratified Articles must be amended or replaced; he had made everything more difficult. It would now be six more years before the "perpetual" Articles could be unraveled, in the form of a new Constitution. That provided for federal taxation and going forward made it considerably easier to amend than by unanimous consent of all the states. There remained the awkwardness of that term "Perpetual". The whole experience was exasperating, but it surely left him and others determined not to be dissuaded by fine points of legal language.

|

| George Washington |

Any perpetual agreement never to allow amendment (except by unanimous consent) is visibly unwise, but that was what confronted those who now proposed to amend the Articles. At the least, it pushed the decision in favor of replacing the whole document. It was easier to brush aside a perpetual legal document, as unreasonable than to argue that obtaining thirteen votes was impossible. George Washington had spent a lifetime constructing a reputation for always keeping his word. If even Washington could agree the situation was unreasonable, the public was of a mind to accept that absolutely anyone should agree. Anyway, the reasoning behind the language in the first place was that thirteen former colonies were joining together for a larger Union which would continue after the Revolution. It was the Union which was meant to be perpetual, not the Articles. Curiously, this change also made it easier to expand the union; imagine the difficulty of obtaining unanimous votes from fifty constituent states. There almost seems to be an ominous political axiom buried in this situation: as the number of voters grows, the majority margin must narrow if a deadlock is to be avoided.

The Revolutionary War, begun in 1775, continued from 1781 (Yorktown) to 1783. Even during four succeeding years of peaceful governance under the Articles, from the Treaty of Paris (1783) to the Constitutional Convention (1787), not a great deal happened. But a few things did come up to test the usefulness of the Articles. The small war between Connecticut and Pennsylvania was settled by the Decision of Trenton, although state boundaries became largely formalities after the country was unified by Article IV of the Constitution. The Northwest Ordinance was passed. And the Constitutional Convention was agreed to. Several flags were tested and adopted. Robert Morris had swept aside the habit of micro-managing the country by Congressional Committee, delegating government departments to bureaucracy in the process. Of all these activities, the most important was the Northwest Ordinance, which demonstrated that important governmental innovations could actually be accomplished under the Articles.

Democracies all like to talk too much. Their constitutions typically run to hundreds of micro-managed pages, and get everyone confused, unless they are unwritten, which is really confusing. It's hard to remember, but the Articles were the first written constitution, and to this day no other former member nation of the British Commonwealth has a written constitution. By giving things a trial run in the Articles of Confederation, we learned what is important and wrote it down. The second time around, tested in war and in peace, we made important revisions. By the time of the Civil War, we had a written governing document that men would die for because they understood it and approved.

Is It Better to Die in America?

The purpose of healthcare financing is to redistribute the pain of paying for it. Otherwise, the patient doesn't want to be sick or die; illness itself is a disincentive to abuse. The concern about abuse mainly arises when someone else pays for it. The indigent patient doesn't want to be sick, either, but somehow that's different. Not only does the public resent the cost, but the public also resents the need for the cost, as well.

Two of the central figures in devising Obamacare -- supposedly free healthcare for everyone -- have framed the issue as to whether it is better to die in America or somewhere else. Just about no one wants to die anywhere, at any time I notice. The mortality figures are too fuzzy to judge whether the extra cost is worth the money, but essentially there isn't enough provable difference among developed nations to assert most care lengthens the lifespan of the patients. Especially for cancer patients. Apparently, the diffusion speed of new knowledge makes it impossible to tell how much it helped. Or else the amount of new knowledge isn't sufficient to show up in such crude data. By that standard, medical care is just as "good", one place or another, one insurance system or another. It just costs more, that's all. When some research laboratory finds a cure for cancer, health care still won't seem to have proved it helped.

But life expectancy will increase; in the long run, costs will come down. It can be very confidently assumed that those who invest their savings early in life will enjoy a more prosperous retirement than those who depend on entitlements.

Mexican Immigration and NAFTA

|

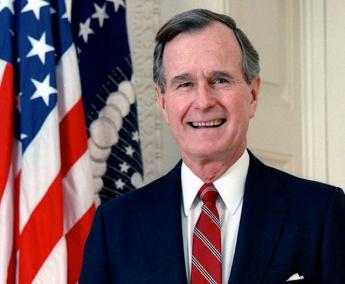

| George H.W. Bush |

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed on December 17, 1992, by President George H. W. Bush for the United States, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney for Canada, and President Carlos Salinas for Mexico. It was intended to eliminate tariffs from the North American continent, with long-run benefits for the three nations who made the agreement. Essentially, it was President Bush's idea, growing out of the long period of public service in which he prepared himself for the Presidency in most of the major components of the American government. After his election, he immediately started to implement the many ideas he had formulated, characteristically worked out in considerable detail, and assigned to government officials he had worked with and knew he could trust. The twin results were that he advanced sophisticated ideas much more quickly than is customary, but then experienced backlash from a public which was accustomed to understanding programs before they assented to them. NAFTA was a prime example of both the advantages and disadvantages of an expedited approach.

Tariffs are a tangled ancient political dispute between nations; George Bush got his two neighbors to sweep them away in a remarkably short time for diplomacy. However, plenty of people benefit from the pork barrel, the unfairness and the economic drag of tariffs, so Bush even got ahead of that opposition, essentially presenting it with a done deal. However, he failed to be re-elected because his fellow Texan Ross Perot campaigned as a third party candidate, thundering about a "giant sucking sound" which was predicted as American businesses would flood into Mexico. Whatever Bill Clinton may think, he won the election as a result of the third-party divisiveness of Ross Perot. And Clinton furthermore got to take credit for NAFTA largely because he claimed the credit. Poppy Bush followed Reagan's strategy of winning by letting others take the credit.

|

| NAFTA |

NAFTA had a lot of minor provisions, but the main feature was to help Mexico with manufactures, compensating for America hurting Mexican agriculture with cheaper United States agricultural imports. The usual suspects howled about the unfairness of such a dastardly deed, but they lost. Helping Mexican manufactures took the tangible form of the "maquiladoras", which were assembly plants from the United States re-located just south of the border, assembling parts made abroad into machinery and other final products, for sale in the United States. The general idea behind this was that Mexican immigration was mostly driven by a hunger for better jobs; give them jobs in Mexico, and they would stay home. That's a whole lot better than an endless border war. Even today, it would be hard to find anyone who would contend that fences, searchlights and police dogs were a superior way to control the borders.

For a while, the maquiladoras were a huge success. But then, China got into the act, paying wages so low that even Mexicans could not live on them. No doubt Ross Perot rejoices that the maquiladoras promptly collapsed, leaving abandoned hulks of factories just across the dried-up Rio Grande. And eventually, we even have tunnels bored under the border and more illegal Mexicans in America than we have people in prison who might take the same jobs. Not the least of the consequences came from the other parts of the same country. Mexico traded an injured agricultural economy for the promise of high-paid manufacturing jobs in maquiladoras. So, masses of impoverished Mexican farmers were made available for illegal immigration, up North.

It is now anybody's guess whether Chinese wages will rise enough, soon enough, to reverse the economics of their destruction of the Mexican economy. The election of a union-dominated Clinton/Obama presidency in the meantime does not bode well for actions which would reverse that result, which now would threaten American-Chinese relations of an entirely different sort. It is true that Chinese wages are relentlessly rising, and that transportation costs now favor assembly-factories closer to the American consumer. But maybe the moment for this approach is passing, or possibly has passed.

REFERENCES

| George H. W. Bush: The American Presidents Series: The 41st President, 1989-1993: Timothy Naftali, ISBN-10: 0805069666 | Amazon |

10 Blogs

The Civil War

The problem was whether it was possible to surrender enough power to govern, but not too much for survival. Slavery was the ultimate test, and America almost didn't survive. After a hundred and sixty years, nearly half of the country feels it should have won the war, even though no one is still alive who experienced either slavery or the war.

Jury Nullification

William Penn demonstrated one of the most incisive legal minds in England by trapping the British courts in what remains a central unresolved dilemma for the law. He was the defendant in his own case. By the South's way of looking at things, it was a pacifist effort to restrain mindless abolitionism. Meanwhile, both sides calculated it would win if the South decided to fight.

William Penn demonstrated one of the most incisive legal minds in England by trapping the British courts in what remains a central unresolved dilemma for the law. He was the defendant in his own case. By the South's way of looking at things, it was a pacifist effort to restrain mindless abolitionism. Meanwhile, both sides calculated it would win if the South decided to fight.

John Marshall's Constitution

New blog 2012-03-06 12:40:48 description

New blog 2012-03-06 12:40:48 description

Joseph Story on Politics Under the Constitution

Joseph Story, Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court during the time of Chief Justice Marshall, had something to say about political parties.

Joseph Story, Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court during the time of Chief Justice Marshall, had something to say about political parties.

Aftermath: Who Won, the States or the Federal?

The auto and the jet plane changed all the rules of the American Constitution of 1787. Curiously, canals were central to the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the other great political innovation of modern times.

The auto and the jet plane changed all the rules of the American Constitution of 1787. Curiously, canals were central to the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the other great political innovation of modern times.

Other Constitutional Issues

New blog 2019-06-03 21:25:22 description

As Europe Learned: Common Currency Without Common Government Spells Trouble

For many years, many nations shared the Spanish doubloon or "piece of eight" as their common currency. Why the Euro couldn't do the same gets to the basics of what money is supposed to be.

American Articles of Confederation, Valuable or Hindrance?

The American Articles of Confederation were devised and then completed in Philadelphia. Correcting their biggest flaws made it easier to accept a sparse Constitution which is hard to amend. But it gave the British a legal way to hang them as rebels.

The American Articles of Confederation were devised and then completed in Philadelphia. Correcting their biggest flaws made it easier to accept a sparse Constitution which is hard to amend. But it gave the British a legal way to hang them as rebels.

Is It Better to Die in America?

New blog 2016-02-17 21:20:34 description

Mexican Immigration and NAFTA

NAFTA was a brilliant innovation by Poppy Bush, but it was perhaps a little too sophisticated.

NAFTA was a brilliant innovation by Poppy Bush, but it was perhaps a little too sophisticated.