2 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Philadelphia's Middle Urban Ring

Philadelphia grew rapidly for seventy years after the Civil War, then gradually lost population. Skyscrapers drain population upwards, suburbs beckon outwards. The result: a ring around center city, mixed prosperous and dilapidated. Future in doubt.

Authors, Writers, Poets, Reporters and Publishers in Laurel Hill Cemetery

Boker, George Henry, (1824-1890), Section A, Lot 91. Poet and dramatist. Helped led its Civil War propaganda Activities.

Bradford, Andrew Section W, Lot 231 Andrew Bradford (1688-1742) published Philadelphia's first newspaper.

Brown, Charles Brockden, (January 17, 1771 - February 22, 1810), an American novelist, historian, and editor of the Early National period, is generally regarded by scholars as the most ambitious and accomplished US novelist before James Fenimore Cooper.

Bullitt, John Christian,(1824-1902)Section P, Lot 52. Lawyer and author of the Philadelphia City Charter.

Childs, George William.(1829-1894)Section K, Lot 337. Publisher of Victorian best sellers and one of Philadelphia great 19th century newspapers-the Public Ledger

Conrad, Robert, (1810-1858). Section 14, Lot 266. A literary figure who served as first Mayor of the Consolidated City of Philadelphia.

Cummings, Brig. Gen. Alexander (1810-1879) Section I, Lot 224 Founded the Evening Bulletin, oversaw procurement and raised troops in Civil War. Governor of the Colorado Territory. Nicknamed "Old Straw Hat."

Curtis, Louisa Knapp. (1852-1910)River Section, Lot 31. Editor of the Ladies Home Journal.

Duane, Mary Morris (Section L, Lot107-112) was a Poet.

Elverson, James. (1828-1911). Section T. Lot 41. Developed the Inquireras a major newpaper.

Fagan, Frances.(Fanny)(1834-1878) Section G, Lot 272, first daughter of John Francis Fagan by his first wife, Mary (Armstrong). Fagan committed suicide and was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery, on 2 February 1878. Poet.

Godey, Louis Antoine. (1804-1878) Section WXYZ Oval. Lot 3. Publisher of America's first great magazine for women-Godey's Lode's Book.

Hale, Sarah Josepha. (1788-1879). Section X, Lot 61. Editor of Godey's Lady's Book, a crusader for women's medical education, and the person chiefly credited with establishing Thanksgiving as a national holiday.

Hildeburn, Mary Jane,(1821-1882) Section G-190. Author of Presbyterian Sunday School stories.

Hirst, Henry Beck.(1817-1874). Section Q, Lot 225. Poet

Hooper, Lucy Hamilton. Section W, Lot 17 was an assistant editor ofLippincott's Magazine from the first edition until 1874. She also wrote for Appleton's Journal and the Evening Bulletin. She wrote several books of poetry and she was also a playwright. One of her plays, Helen's Inheritance, had its premiere at the Madison Square Theater in NYC. After moving to Paris in 1874, she became the "Paris correspondent" for various American newspapers. She was also a novelist, with one of her novels, Under The Tricolor, causing quite a stir. It was a thinly-veiled satire of the lives of certain expatriates who were living in Paris at the time.

Kane, Elisha Kent. Section P, Lot 100. Elisha Kent Kane(1820-1857) became famous for his arctic explorations. Kane's publications include: "Experiments on Kristine with Remarks on its Applications to the Diagnosis of Pregnancy," "American Journal of Medical Sciences, n.s., 4 (1842), The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin, A Personal Narrative, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1854, and Arctic Explorations in Years 1853, '54, '55, Philadelphia: Childs and Peterson, 1856.

Lea, Henry Charles.(1825-1909) Section S, Lot 49. Pro-Northern propagandist during the Civil War, Civic Reformer, and author of a classic history of the Spanish Inquisition. Sculpture by Alexander Stirling Calder.

Leslie, Eliza. (1787-1858) Section6, Lot 45. Author of MissLeslie's Directions for Cookery (1851)and other cookbooks.

Lippincott, Joshua B. (1831-1886)Section 9, Lot 118. Founder of the distinguished Philadelphia publishing company.

Marion, John Francis. (1922-1991) Section S, Lot 118. Philadelphia historian, author, and gentlemen.

Mc Michael, Morton.(1807-1879) Section H, Lot 45. Publisher of the North American, mayor of Philadelphia, and president of the Fairmount Park Commission.

Neal, Joseph Clay, (1807-1847) Section P, Lot 71. Editor and humorist, best known for Charcoal Sketches in a Metropolis.

Read, Thomas Buchanan. (1822-1872) Section K, Lot 206. Both poet and sculptor, Read is best remembered for his Civil War poem "Sheridan's Ride".

Singerly, William. (1832-1898) Section K, Lot 235. Made fortunes in street railways, real estate, knitting mills. Published the Philadelphia Record.

Townsend, George Alfred.(1841-1914) Section 9, Lot 98. One of the most important American Journalists during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Wireman, Katharine Richardson. Section 9, Lot 160. was an illustrator who studied with Howard Pyle. She worked for the magazines that Curtis Publishing produced.

Wister, Owen. (1860-1938) Section J, Lot 206. Author of The Virginian. American writer whose stories helped to establish the cowboy as an archetypical, individualist hero. Wister and his predecessor James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) created the basic Western myths and themes, which were later popularized by such writers as Zane Grey and Max Brand.

Acorn Club of Philadelphia

.JPG)

|

| Trish Brown |

Trish Brown visited the Right Angle Club recently, and told us about our club's feminine neighbor at 1519 Locust Street. She's the charming, witty new club manager of the Acorn Club, who often left this audience of men a little nonplussed about whether she was twitting us. For example, she told us that her club's policy about publicity. The policy states in one place that publicity is welcome, but in another place mention it must not mention the club's name.

.JPG)

|

| Acorn Club |

The Acorn is the oldest club for women in America, having been founded by Mrs. Thomas Biddle in 1889. The ladies of the neighborhood had taken to having walks together, and out of this association came the club, which soon found it needed a place to come in out of the rain. It started at 1642 Pine Street and was in five different locations until the present building was built in 1956. At one time it had 900 members, now has 700, of which 200 live more than 50 miles away. Unlike men's clubs, which are seeing a migration from lunch to dinner, the Acorn heavily favors lunch, usually on the days of local art, musical and literary events. It's one of two Platinum Clubs in Philadelphia, a quality designation for the top 200 (of 6000) national clubs. If you are interested in their cuisine, it may be sufficient to know that the top favorite dessert is creme brulee.

The club dining room seats 110, with 80 seats in other rooms, and has a staff of 11. There's definitely a dress code, but for women that's a little hard to define. Trish observes that it seems to lean toward pearls.

There's a cross-over alliance with the Philadelphia Club, where the husbands of many Acorn members belong. Both clubs are doing their best to adjust to changing times and customs, but Alfie Putnam once noticed a seemingly enduring feature. The flag, he said, is mostly at half-mast.

Bergdoll the Rich Draft Dodger

|

| Grover Cleveland Bergdoll |

Grover Cleveland Bergdoll was one of the great playboys during the era between the Spanish American War and World War I. Although the money came from his beer-baron father, he was in the newspapers as one of the early owners of an airplane, one of the dare-devils racing about in open cars, and of course successful with girls.

His father Louis (1825-94) had emigrated from Germany, bringing with him the new technique of making lager beer by brewing it in the cold, and quickly exploiting its popularity into thousands of barrels of beer a day. Although it is always hard to say just who invented a technique like that, there seems little doubt that Bergdoll & Schemm was responsible for transforming the area north of Spring Garden Street into a booming area of breweries, consuming huge amounts of ice and ice water, wood staves for beer barrels, horses to drag beer to the beer gardens, and energizing railroads to import raw materials and carry away the barrels of beer. The refrigeration industry flourished and spread out into air conditioning. Bergdoll was a mighty force in Philadelphia industry.

|

| Bergdoll Mansion |

The Bergdoll house was located on 21st Street, not far from the Eastern State Penitentiary, in the very upscale neighborhood called Fairmount. The neighborhood was isolated by the "Chinese Wall" of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and more importantly by the slashing through of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Eventually, the advent of Prohibition destroyed Philadelphia's brewery industry and its associated beer gardens. The Fairmount region declined into a slum, particularly after the 1929 Stock Market Crash, and upper crust Philadelphia fled blocks and blocks of huge mansions, too big to heat and clean, and also too big and substantial to tear down. So the Bergdoll mansion has been there all along, but there was just no one around to look at it. With the gentrification of the Fairmount region at the turn of the 21st Century, there it sits. a brownstone Pyramid, or Parthenon. A lot of wild stories circulate in the neighborhood, but very few of the new neighbors know very much about it.

It's just possible that the brownstone Widener mansion on North Broad Street is bigger, and certainly the Elkins, Stotesbury and Montgomery mansions in the far suburbs are a lot bigger. But this brownstone edifice in the center of town is impressively large enough to count for something, filling roughly half a square block if you include what look like stables of the same architectural style, and the double houses which suggest some members of the family lived next door. Even these smaller outbuildings are a great deal larger than the average city mansion.

|

| Bergdoll Mansion |

The size of the place makes it easier to understand how Grover Cleveland Bergdoll could be hidden there as a draft dodger for years. In fact, local rumor often has it that he stayed there for thirty years, but it was really only about three. A book by Roberta E. Dell, called The United States Against Bergdoll supplies considerably more detail. One has to suppose that this strongly German family was opposed to American participation in World War I, and the government's violent reaction to his draft objection reflected concern that the very large German-American population might rise up and interfere with Woodrow Wilson's decision to enter the War on the Allied side. In any event, Grover's mother hid him away in the extensive mansion complex until that war seemed safe over, but he was immediately apprehended and put on trial when he emerged. Somehow or other, he managed to convince the authorities that he should be released under guard in order to go dig up an enormous fortune in gold that he had buried. The agents guarding him were put up as guests in the big mansion, apparently unable to resist the big treat. But it was a ruse, a getaway was waiting and off he sped, ending up in exile in a little town a few miles from Heidelberg, Germany. It was there that he married a local German girl and spent an apparently comfortable exile until after the Second World War. There were rumors and stories, however. A couple of kidnappers broke in on him in an apparent effort to take him over the French border, but Bergdoll killed one of them. Even after World War II, all was not forgiven; he came home, was immediately apprehended and tried, and spent a brief time in jail. He died in 1966.

Those who are sufficiently fascinated by his story, can even live in his house. It's been renovated, and rents out as Bergdoll Mansion Apartments.

Philadelphia City-County Consolidation of 1854

|

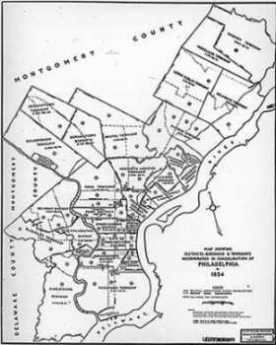

| Consolidation Map 1854 |

Philadelphia is still referred to as a city of neighborhoods. Prior to 1854, most of those neighborhoods were towns, boroughs, and townships, until the Act of City-County Consolidation merged them all into a countywide city. It was a time of tumultuous growth, with the city population growing from 120,000 to over 500,000 between the 1850 and 1860 census. There can be little doubt that disorderly growth was disruptive for both local loyalties and the ability of the small jurisdictions to cope with their problems, making consolidation politically much more achievable. A century later, there were still two hundred farms left in the county which was otherwise completely urbanized and industrialized. For seventy-five years, Philadelphia had the only major urban Republican political machine. By 1900 (and by using some carefully chosen definitions) it was possible to claim that Philadelphia was the richest city in the world, although this dizzy growth came to an abrupt end with the 1929 stock market crash, and the population of Philadelphia now shrinks every year. In answering the question of whether consolidation with the suburbs was a good thing or a bad thing, it was clearly a good thing. But since Philadelphia is suffering from decline, it becomes legitimate to ask whether its political boundaries might now be too large.

|

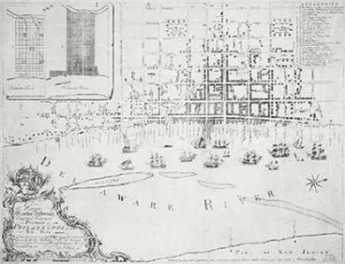

| Philadelphia Map 1762 |

The possible legitimacy of this suggestion is easily demonstrated by a train trip from New York to Washington. The borders of the city on both the north and the south are quickly noticed out the train window, as the place where prosperity ends and slums abruptly begin. In 1854 it was just the other way around, just as is still the case in many European cities like Paris and Madrid. But as the train gets closer to the station in the center of the city, it can also be noticed that the slums of the decaying city do not spread out from a rotten core. Center City reappears as a shining city on a hill, surrounded by a wide band of decay. The dynamic thrusting city once grew out to its political border, and then when population shrank, left a wide ring of abandonment. It had outgrown its blood supply. Prohibitively high gasoline taxes in Europe inhibit the American phenomenon of commuter suburbs. The economic advantage of cheap land overcomes the cost of building high-rise apartments upward, but there is some level of gasoline taxation which overcomes that advantage. Without meaning to impute duplicitous motives to anyone, it really is another legitimate question whether some current "green" environmental concerns might have some urban-suburban real estate competition mixed with concern about global warming. Let's skip hurriedly past that inflammatory observation, however, because the thought before us is not whether to manipulate gas taxes, but whether it might be useful to help post-industrial cities by contracting their political borders.

Before reaching that conclusion, however, it seems worthwhile to clarify the post-industrial concept. America certainly does have a rust belt of dying cities once centered on "heavy" industry which has now largely migrated abroad to underdeveloped nations. But while it is true that our national balance of trade shows weakness trying to export as much as we import, it is not true at all that we manufacture less than we once did. Rather, manufacturing productivity has increased so substantially that we actually manufacture more goods, but we do it with less manpower and less pollution, too. The productivity revolution is even more advanced in agriculture, which once was the main activity of everyone, but now employs less than 2% of the working population. This is not a quibble or a digression; it is mentioned in order to forestall any idea that cities would resume outward physical growth if only we could manipulate tariffs or monetary exchange rates or elect more protectionist politicians to Congress. Projecting demographics and economics into the far future, the physical diameters of most American cities are unlikely to widen, more likely to shrink. If other cities repeat the Philadelphia pattern, the vacant land for easy exploitation lies in the ruined band of property within the present political boundaries of cities, or if you please, between the prosperous urban center and the prosperous suburban ring.

Many American cities with populations of about 500,000 do need more room to grow, so let them do it just as Philadelphia did a century ago, by annexing suburbs. But there are other cities which have lost at least 500,000 population and thus have available low-cost low-tax land which would mostly enhance the neighborhood if existing structures were leveled to the ground. Curiously, both the shrunken urban core and the bumptious thriving suburbs could compete better for redeveloping this urban desert if the obstacles, mostly political and emotional, of the political boundary, could be more easily modified. But that's also just a political problem, and not necessarily an unsolvable one.

Reservoir on Reservoir Drive

William Penn planned to put his mansion on top of Faire Mount, where the Art Museum now stands. By 1880, long after Penn decided to build Pennsbury Mansion elsewhere, city growth outran the capacity of the new reservoir system which had then been placed on Fairmount. An additional set of storage reservoirs were placed on another hill across East River (Kelly) Drive, behind Robert Morris' showplace mansion now called Lemon Hill (Morris merely called it The Hill); the area was eventually named the East Park Reservoir. In time, trees grew up along the ridge and houses got built; the existence of these reservoirs right in the city was easily forgotten, even though the towers of center city are now plainly visible from them. These particular reservoirs were never used for water purification; that's done in four other locations around town, and the purified water is piped underground to Lemon Hill, for last-minute storage; gravity pushes it through the city pipes as needed.

Now, here's the first surprise. Water use in Philadelphia has markedly declined in the past century. That's because the major water use was by heavy industry, not individual residences, so one outward sign of the switch from a 19th Century industrial economy to a service economy is -- empty old reservoirs. Only one-quarter of the reservoir capacity is in active use, protected by a rubber covering and fed by underground pipes. The rest of the sections of the reservoir are filled by rain and snow, but gradually silting up from the bottom, marshy at the edges. Unplanted trees have grown up in a jungle of second-growth, attracting vast numbers of migratory birds traveling down the Atlantic flyway. Although there are only a hundred acres of water surface here, the dense vegetation closes in around the visitor, giving the impression of limitless wilderness, except for the center city towers peeping through gaps in the forest. It's fenced in and quiet except for the birds. For a few lucky visitors, it's easy to get a feeling for how it must have looked to William Penn, three hundred or more years ago, and Robert Morris, two hundred years ago. In another sense, it demarcates the peak of Philadelphia's industrial age, from 1880 to 1940, because that kind of industrialization uses a lot of water.

The place, in May, is alive with Baltimore Orioles. Or at least their songs fill the air and experienced bird watchers know they are there. Even a beginner can recognize the red-winged blackbirds, flickers, robins, and wrens (they like to nest in lamp posts). The hawks nesting on the windowsills of Logan Circle suddenly makes a lot more sense, because that isn't very far away. In January, flocks of ducks and geese swoop in on the water surface, which by spillways is kept eight feet deep for their favorite food. Just how the fish got there is unclear, perhaps birds of some sort carried them in. The neighborhoods nearby are teeming with little boys who would love to catch those fish, but it's fenced and guarded much more vigorously since 9-11. In fact, you have to sign a formal document in order to be admitted; it says "Witnesseth" in big letters. Lawyers are well known for being timid souls, imagining hobgoblins behind every tree. However, there are some little reminders that evil isn't too far away. Just about once a week, someone shoots a gun into the air in the nearby city. It goes up and then comes down at random, with approximately the same downward velocity when it lands as when it left the muzzle upward. That is, it puts a hole in the rubber canopy over the active reservoir, which then has to be repaired. No doubt, if it hit your head it would leave the same hole. So, sign the document, and bring an umbrella if the odds worry you.

A treasure like this just isn't going to remain as it is, where it is. It's hard to know whether to be most fearful of bootleggers, apartment builders or city councilmen, but somebody is going to do something destructive to our unique treasure, possibly discovering oil shale beneath it for example, unless imaginative civil society takes charge. At present, the great white hope rests with a consortium of Outward Bound and Audubon Pennsylvania, who have an ingenious plan to put up education and administrative center right at the fence, where the city meets the wilderness. That should restrict public entrance to the nature preserve, but allow full views of its interior. Who knows, perhaps urban migration will bring about a rehabilitation of what was once a very elegant residential neighborhood. And push away some of those reckless shooters who now delight in potting at the overhead birds.

This whole topic of waterworks and reservoirs brings up what seems like a Wall Street mystery. Few people seem to grasp the idea, but Philadelphia is the very center of a very large industry of waterworks companies. The tale is told that the yellow fever epidemics around 1800 were the instigation for the first and finest municipal waterworks in the world. There's a very fine exhibit of this remarkable history in the old waterworks beside the Art Museum. But that's a municipal water service; why do we have private equity firms, water conglomerates, hedge funds for water industries, and other concentrations of distinctly private enterprise in the water? One hypothesis offered by a private equity partner was that the success of the municipal water works of Philadelphia stimulated many surrounding suburbs to do the same thing; it was surely better than digging your own well. This concentration of small and fairly inefficient waterworks around the suburban ring of this city might well have created an opportunity for conglomerates to amalgamate them at lower consumer cost. Anyway, it seems to be true that if you want to visit the headquarters of the largest waterworks company in the world, you go about seven miles from city hall and look around a nearby shopping center. If you are looking for the world's acknowledged expert in rivers, you go to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia on Logan Square and look around for a lady who is 104 years old. And if you have a light you are trying to hide under a barrel, come to Philadelphia.

Ms. Mayor

|

| Mayor Letitia Colombi |

One of the great treasures of Haddonfield is a letter from Benjamin Franklin to the husband of Elizabeth Haddon, to the effect that she was the most forceful woman of the region. Indeed, it is part of the tradition of the Haddonfield Meeting of Friends that the men's meeting and the women's meeting met is separate rooms and kept separate minutes at that time. Elizabeth was the clerk of the women's meeting, and while the men's meeting would sign the minutes as "The Meeting on Stoy's Landing" or the "Meeting near Cooper's Creek" or something else topical, the minutes of the women's meeting were consistently signed in a single way. They were from the meeting in Haddonfield. Ultimately, everybody gave up and named the town Haddonfield.

|

| Haddonfield Borough Hall |

Without being able to recall a single other woman who was Mayor of the town, it does seem appropriate that its present mayor is a lady and a forceful one at that. Letitia Colombia has been on the Borough Board of Commissioners for nearly twenty years and seems likely to remain Mayor for as long as she wishes. In the tradition of forcefulness, a number of old timers in the town remember when she first got elected by knocking on every door in the town, and then marched down the main street in the July 4th parade, wearing high-heeled red shoes.

The Right Angle Club was curious to see what this was all about, and her performance was a brilliant demonstration why politics is a full-time sport of every town in Texas. Odessa, her home town, is a few miles from Midland-where-the-oil-comes from, and she and Laura Bush probably attended the same high school. They are certainly both members of the same school.

|

| Al Driscoll |

In many ways it was Al Driscoll who as Mayor asked why Haddonfield couldn't be like Princeton, where he once went to school. The answer he got was to change the zoning ordinances and then just wait thirty years. It worked fairly well, although Haddonfield got a parking and traffic problem along with the good features of looking like Princeton. But it wasn't Tish's way; one might say it wasn't the Texas way. She hired some consultants at a cost of $125,000 to work out a detailed plan for changing Haddonfield for the better, and then followed the plan. It included a list of the kind of stores you do and don't want in a town of this type and the general strategy of attracting them. The zoning laws are sort of like Princeton's, but different enough to matter. Year by year, you can see the town change from a sleepy little place into a lively place to be. There are no empty lots in Haddonfield; to change the town, you have to remodel everything, house by house. On a summer evening, there are throngs of people on the sidewalks downtown, entertained by three or four street bands, wandering up and down at the sidewalk sales of the merchants. Haddonfield is "dry" in the sense that liquor sales are prohibited; that policy was recently reconfirmed by a four-to-one vote. But it hasn't kept restaurants away. The residents like BYOB a lot, and fully understand what it means.

Taxes in Haddonfield are, well, generous. But Haddonfield gets no state school aid; its schools are much like a thirty-million-dollar private school system, run by locals to local taste. And a quarter of our taxes go to Camden County. Tish boldly announces we get nothing whatever for those taxes in return. With a slogan like that, it's pretty hard to doubt she's a Republican.

REFERENCES

| Heroines of Haddonfield 1713-2013: Christie Castorino: ISBN: 978-1-4836-2719-9 | Xliris |

| Posted by: Sasa | Mar 12, 2012 7:50 PM |

| Posted by: John | Mar 21, 2010 8:45 PM |

| Posted by: George Fisher | Aug 12, 2007 9:10 PM |

| Posted by: Paul Glover | Aug 12, 2007 9:54 AM |

6 Blogs

Authors, Writers, Poets, Reporters and Publishers in Laurel Hill Cemetery

Authors, Writers, Poets, Reporters and Publishers in Laurel Hill. Naturally, lots of other people are buried there, too.

Acorn Club of Philadelphia

.JPG)

Bergdoll the Rich Draft Dodger

Philadelphia City-County Consolidation of 1854

Prior to 1854, Philadelphia City was one of twenty-nine political entities within Philadelphia County. After that, it became one big city without suburbs. Growth pressure now reverses toward suburbs without a city. Political boundaries should thus shift inwardly.

Prior to 1854, Philadelphia City was one of twenty-nine political entities within Philadelphia County. After that, it became one big city without suburbs. Growth pressure now reverses toward suburbs without a city. Political boundaries should thus shift inwardly.

Reservoir on Reservoir Drive

Ms. Mayor

The current, and long time, Mayor of Haddonfield New Jersey is a lady from Odessa, Texas.

The current, and long time, Mayor of Haddonfield New Jersey is a lady from Odessa, Texas.