2 Volumes

Reminiscences, In Memoriam, The Right Angle Club,

Philadelphia doesn't toot its own horn very much. A central part of its charm is the wealth of anecdotes, and many charming characters, known only to insiders. You have to be a real Philadelphian to know very much of this lore.

Philadelphia Reminiscences

Volume of Philadelphia Historical Episodes

Personal Reminiscences

One of the features of aging past ninety is accumulating many stories to tell. Perhaps fewer are left alive to challenge insignificant details.

My Years at Stockley

For forty-six years, I drove three hundred round- trip miles from Philadelphia to Stockley, Delaware -- once a month on Saturdays. That takes a whole day, so it kind of means I spent a year at sixty miles an hour, going and coming. In Delaware, they speak of going “South of the Canalâ€, to indicate the little state of Delaware is actually two states or at least two cultures. North of the Delaware-Chesapeake ship canal is the posh little city of Wilmington, where most of the major New York banks are moving to enjoy the special banking laws, and where the Dupont family held majestic court over its Ivy League Camelot. Wilmington has more lawyers than anywhere or at least more white shoe patrician lawyers than anywhere. Little Delaware generated special laws for the benefit of corporations, so a whole hive of corporation lawyers generated an industry of pretending that General Motors and IBM are headquartered there. Those lawyers were once so remote from the graduates of second-rate (i.e. state rather than national) law schools making a living as plaintiff lawyers, that even the doctors in Wilmington were on cordial terms with the Wilmington lawyers.

South of the Canal was something else. I saw burning crosses on several occasions, and my trip took me past two race tracks for horses and two for beat-up jalopies that smash into each other for the fun of it. To be fair about it, I was shot at twice, once below the canal, and once in Wilmington, that's another story. The incident below the canal was not terribly spectacular; I just heard a loud noise as I drove past Elks lodge, or maybe a Moose lodge, and there was a nice round hole in my fender when I got out of the car. I suppose someone in the lodge was just careless with his gun, but it is not impossible that I had crowded a pick-up truck which retaliated with fair warning.

I met a nice lady from Rehoboth who tells me she remembers when the highway was built; before 1930 or so, there was no road connecting lower Delaware with the outside world. The native people speak with an accent which isn't quite Southern and which is said to be very close to true Elizabethan English. The area was settled by Swedes before the English came, so the people are quite handsome in a sort of Daisy Mae, L’il Abner way. The highway has an interesting history. Coleman DuPont purchased the land and built the highway at his own expense. If you know anything about rural legislatures, you can guess what happened next. He offered the highway to the State and the legislature refused to accept the maintenance costs. When he then hired his own police force to patrol the highway, the legislature reconsidered and accepted his offer to give them the highway.

My trips to this area have their destination at the Hospital for the Mentally Retarded in Stockley, Delaware. In spite of the way it is spelled, it is pronounced "Stokely". A state cop once forgave my speeding violation when I told him I had been at "Stokely". He said that in spite of my out-of-state license plates, I must be telling the truth if I knew how to pronounce it. The hospital has always kept a sign-in log in the administration building, and it is fun to see my signatures going back to 1958, month after month. I've had a couple of close calls or near-accidents on the highway which I haven't told my wife about, and on two occasions the ice or fog was so bad I had to turn around and come home without completing the trip. The trip ordinarily isn't so bad. The car is on cruise control, there are medical education tapes to play (Audio Digest, courtesy of the California Medical Association), and a sort of hypnosis makes you forget where you are going until you get there.

The medical director is a nice young fellow who has a practice in a nearby (25 miles) town and stops by for a few hours a day. Except for him, just about every resident doctor in thirty years has been foreign-born, and I would judge, very poorly paid. So, several years before I came to Stockley, someone had the idea of bringing in consultants from Wilmington, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. In the early days that was reasonably easy to do, because the hospital was filled with six hundred perfectly fascinating cases. I've seen several albinos and one thirty-year-old who was no bigger than an infant in arms. They used to have a number of cases of grotesque hydrocephalus, where the poor child grew a head larger than you could put your arms around and which would develop huge bedsores because the child couldn't move his head, let alone lift it. Because the Delmarva Peninsula has been a closed society for over three hundred years, there are lots of cases of rare inherited diseases. I have seen many cases of disorders that other doctors have only maybe read about, and I must admit I loved the experience.

But you know after you spend as much time with them as I have, they stop being interesting cases and become individuals, with names and personalities. Since the aging process is accelerated in several common diseases like Mongolism, I have known some of the patients' as little children, then as adults, and finally as dying withered victims of senility. Many times, I have watched the central agony of mental retardation; the children inevitably outlive their parents and ultimately have no one to love them except the institution.

In that role, Stockley does pretty well, although perhaps not as well as it used to do. The switch seems to have happened with the John Kennedy administration when money for the retarded became abundant. That landmark was especially memorable on a Saturday when the Russians menaced us over Cuba. I never knew we had so many eight-engined bombers as circled over the Dover Air Force Base that day. Years later, a pilot brought his son to see me, and I asked him. "Yup," he said. "we were carrying eggs, all right." "Picked them up in Alaska."Ethnic Cemeteries

|

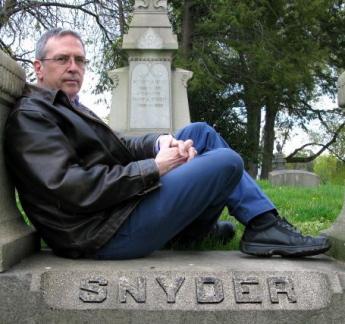

| Ed Snyder |

Schneider spelled Snyder (or Snider) is almost certainly a Pennsylvania Dutch surname in some sense. I presume Ed Snyder is of that derivation, but at any rate, he addressed the Right Angle Club recently on the subject of photographing cemeteries. Along the way, he seems to have picked up a lot of historical facts about graveyards, which he put together into a fascinating story. I get the impression many of the traditions he described originated in Europe and were transported here by various waves of immigration. So we don't have much information about the origins of those customs, except by inference.

|

| Meeting House on 4th |

The Quakers who settled Philadelphia in the early 1680s didn't believe in putting your name (or your picture) on anything, feeling that would be idolatry. The tradition, plus the yellow fever epidemics, accounts for the Meeting House at Fourth and Arch having forty thousand people buried in its yard, in five layers, but above them only two tombstones. Just why those two were exceptions is not described. Jonathan E. Rhoads, the famous University of Penn surgeon, has his name on a pavilion at the hospital to which he raised a loud objection, but he finally died there himself, saying, "It didn't look so bad." So we have comparatively few early Quaker monuments still standing in the Quaker City, although it does seem pretty certain the Quakers are not responsible for the midnight vandalism now sweeping the country, toppling tombstones. In any event, there definitely is an anti-cemetery movement going around our nation, possibly dating back to the days when bodies of parishioners were buried in churchyards if they were in good standing, sort of a giant compost heap. On the other hand, some people remember that Antigone went to some lengths to recover and honor her dead brother on the battlefield of ancient Greece. And that one of the reasons the Romans fed the early Christians to the lions was their horror at the retention of the bones of ancestors in the catacombs. Christians actually took residence in the mortuaries in the expectation of a second coming for everybody. The Mormon infatuation with genetic ancestors may be part of this concept.

|

| Laurel Hill Cemeteries |

It has been said that if you stick a shovel in the ground anywhere, you will encounter a cemetery, but not in Philadelphia. Somewhere around 1830, we imported the French set of traditions of cemeteries, which you can still see as the questionable tombstones of Abelard and Heloise outside Paris. Laurel Hill in Philadelphia was started as an intentional commercial imitation, at a time when you had to take a boat on the Schuylkill to get there, taking the whole family along to have an all-day picnic among your ancestors; and mighty industrial potentate families competed to construct the biggest most expensive mausoleum for the family. Laurel Hill has since fallen into some disrepair, but there is a restoration movement actively repairing it, collecting donations, tracing histories, etc. Neill Bringhurst, a former president of the Right Angle Club, was once the owner, but he vigorously disliked the whole idea and sold it. Woodland, near the University of Pennsylvania, is the other surviving cemetery of this elegance, and it is kept up much better than Laurel Hill, except for the tangled bushes around the periphery to maintain privacy. Woodland is right next to an extensive trolley-car terminal, thus conveying some idea of its former popularity. Prior to being a cemetery, it was the mansion site of Andrew Hamilton, whom George Washington used to visit on his way to Mount Vernon. As you recall, this Hamilton was the original Philadelphia Lawyer, who went to New York to defend the freedom of speech of Peter Zenger the newspaper man accused of telling the truth when he slandered the Governor. Considering the successor governors of New York, it's a good thing he won the case. History has it he was a young unrecognized lawyer, but in fact, Hamilton was the most eminent lawyer of his time, having originally purchased what is now Independence Hall.

|

| Marble Angels |

The traditions of marble angels hovering over tombstones seem to have been imported by Irish and Italian immigrants and are reflected in their present cemeteries. And the Pennsylvania Dutch tombstones and records are intact in Hummelstown PA, dating back to the Seventeenth century. It reflects that this particular branch landed in New York, went up to the Hudson to Kingston, and back down to the Harrisburg area on the Susquehanna. Meanwhile, the Quakers further East were burying their dead in layers without "markers".

There's probably a lot more to this history, but burials are sort of private affairs, so most church groups are unaware of dissenting attitudes, not very far away from them.

The Zimmerman Telegram

|

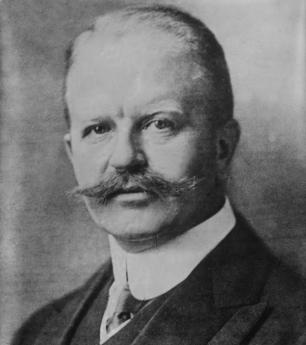

| Arthur Zimmermann |

Sometime in February 1917, Zimmerman the German foreign minister sent a telegram to the President of Mexico, in code. The Germans sensed their submarine warfare might win the war for them, he wrote, and so it might be very helpful to have a second front attacking the allies' main supplier, the United States. Germany would then win World War I, able to give Mexico --Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The British intercepted the telegram, decoded it, and wasted no time putting the translation on Woodrow Wilson's desk.

Wilson had just won a Presidential election on the platform, "He kept us out of the war." Furthermore, the Germans were the single largest ethnic minority in America. But no matter. Nevertheless, within a few days, Wilson stood before a joint meeting of Congress urging them to declare war on Germany.

|

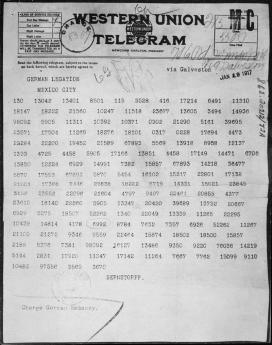

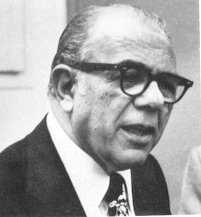

| Telegram in Code |

The consequences were immediate: the German minority was cowed with shame and counting World War II as a continuation of World War I, sixty million people were subsequently killed because of a single heedless telegram. In retrospect, Wilson should have kept it quiet, privately negotiating something from Germany in return for ignoring the thoughtless telegram, and maybe keeping us out of two World wars. That's the sort of thing that gets played around with when a responsible leader creates an uproar over catching an enemy with red hands. Otherwise, the carelessness tempts diplomats to assume he really did want a war, and needed a pretext for it.

It may violate the Constitution or some partisan law created by Congress, but it's the way diplomacy has been conducted ever since--well, since Benjamin Franklin was Ambassador to France, at any rate. It isn't exactly leadership, but it might have saved millions of lives. Muhlenberg told us, "There's a time to preach, and a time to fight." What he seemed to forget was the part about preaching.

Deputy Managing Director

|

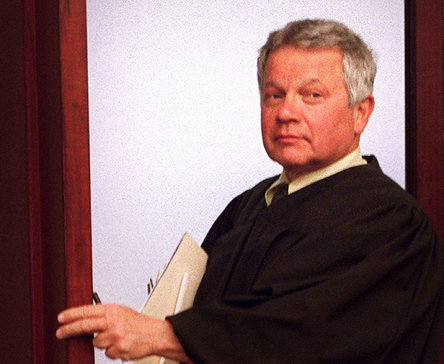

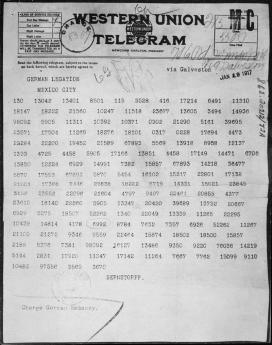

| Judge Benjamin Lerner |

The Deputy Managing Director of Philadelphia, former Judge Benjamin Lerner, honored the Right Angle Club by coming to lunch, recently. He immediately improved our opinion of him by first explaining why he resigned as Judge.

It seems the Inside Baseball of the last Mayor's election shifted the politics quite a lot. Under Mayor Nutter, the department heads reported to the Mayor, but under the new Mayor Kenney, everybody reported to the Managing Director. So Judge Lerner promptly resigned his judgeship and became Deputy Managing Director, if you see the drift of the power shift. He had become exercised about the drug problem in Philadelphia, wanted to do something, and knew the ropes to get it done. You've got to like a man like that.

It doesn't matter what happened to get him mad. The drug situation in this town is a disgrace, and any number of reasons might have got the Judge angry. It's too early to know what he can accomplish in his short time in office, but I have every confidence that if he can't improve things, it's time for all of us to move to another city. Because no one can fix it if he can't.

0

|

| Drug Situation |

In fact, I happen to know something he admitted he didn't know. Several years ago I was mugged in the middle of a police stake-out, so they caught the culprit. That's a pretty open and shut case, but the defense attorney apparently tried to stall me out of being a witness. For nine --nine -- consecutive trials, I canceled appointments and appeared at 9 AM. By the afternoon, I sat there waiting to be told the trial was postponed -- for a prisoner in custody, no less. In any event, I then watched nearly a hundred trials during these nine periods, and every one of the defendants told the Judge he had been smoking drugs, outside the courtroom in the corridor. Well, as a witness I was free to walk around, and I can tell you nobody was smoking drugs in the corridor. I knew for a fact they were telling the judge they were addicts when they weren't. I haven't the slightest idea why they were doing this, but I presume they had discovered some loophole in the law and were exploiting it. A rule that drug addicts escape a jury trial might be a plausible explanation, but I simply don't know.

The Judge agreed with me he had no idea of this behavior, or if it continued to happen. But I am willing to bet, it's now going to stop.

Suited To A "T"

|

| Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid |

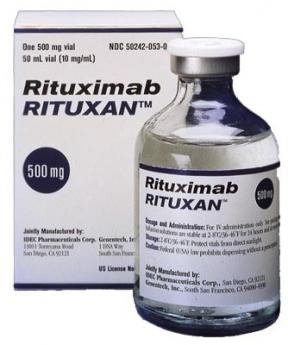

After sixty years as a doctor, it's a little disconcerting to find I have a disease I never heard of. It's better in a way, but in this sense it is worse, to be cured by a treatment I never heard of, either. The disease is mucous membrane pemphigoid, and the cure is Rituxamide. Am I right? Most readers have never heard of either one, but like just about every other patient, I think you all must just be panting to hear about it.

|

| Rituximab |

It turns out I had heard about the disease, but someone had changed its name from lichen planus to mucous membrane pemphigoid. The drug, Rituximab, has been around since 1997, treating rheumatoid arthritis, so it's not completely novel, either. It simply hadn't been used for this condition, which was rare. When we got semantic issues straightened out, and I had experienced a second round of treatment, I attended a seminar on lung cancer. That's the sort of thing doctors do for entertainment.

To my puzzlement, I was told a "me, too" variant of this same drug extended the life of lung cancer patients, but only if they were heavy smokers who quit smoking. That sounded peculiar, essentially saying you live longer from lung cancer if you smoke heavily and don't quit. You get a little euphoric when you take a steroid drug to ease the Rituximab, so I was overcome with the audacity to go to the microphone and announce I thought they lived longer, not because it helped the lung cancer, but because they lived longer by having fewer heart attacks and strokes from the smoking they had quit. Of course, I was politely told I didn't know what I was talking about. But an immunologist in the audience rose to say he agreed with me, because he had been giving the drug to practically every patient in his immunology practice, and quite a few of them got better. (To explain, the drug knocks out the T cells, which mediate most autoimmune diseases, so it sounded plausible.) So that's where matters stand. After everybody scrambles to try the drug on various autoimmune patients, some sort of order will probably emerge.)

But before everyone who reads this demands that his doctor gives him this drug for itchy skin, let me tell you the subsequent story. My insurance company sent me what is known as an "EOB" (explanation of benefits) which had two numbers on it. In the upper left-hand corner, it said my bill was $67,000. In the lower right -hand corner, it said the amount owed was $0.00. Somewhere between the two numbers is the amount you would have to pay if you didn't have insurance, the rest is someone's mark-up. I set about to find out how much the drug really costs to manufacture, and it's hard to find out. Someone said $4, but I can scarcely believe it.

Litchfield to Wilkes Barre, Today

To go from Connecticut to Pennsylvania without going through New York City seems at first a puzzling proposal. After all, New York is in the way. But a couple of centuries ago the Connecticut Yankees really did make it through the mountains, fought three little wars called the Pennamite Wars, and briefly made Wilkes Barre into part of Litchfield County. Because there has been comparatively little settlement along the trail, taking the trip today is the same mostly mountainous, journey. There are no Indians, but the mountains and rivers are the same. You still have to cross the Hudson, Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers but it's a beautiful trip at any time, particularly so during the autumn leaf season. Litchfield to Wilkes Barre: Millions of people live within a day's drive, but it's a good idea to pack a box lunch and fill your tank before leaving.

Lithuanian Law

The Right Angle Club was recently entertained by its rugby-playing, Kilimajaro-climbing member, John Wetzel, about his two-week stint teaching law students at the University of Vilnius. This ancient Lithuanian institution was founded in the 15th Century by Jesuits, and after a bumpy history of invasions and occupations has now re-established itself. It participates in Erasmus mobility, meaning it is one of 47 European universities which exchange credentials and permit students from any one of them to take courses in any other member of the association; evidently, similar mobility of faculty is also part of the concept. It sounds like a great idea, which American universities might well consider.

For reasons not entirely clear, 75% of the law students at Vilnius are female, and the whole local legal profession is similarly woman-dominated. John made several allusions to the general pulchritude of his students, which a class picture with him confirms. One striking feature of such a picture is how slim the ladies are; this is another European feature our own representatives might consider imitating. Since there are 2500 law students in a country of 3 million inhabitants, whose main industries are agricultural, balance is restored by only admitting 15% of the graduates to a passing grade on the bar examinations. It seems remarkable that studying law remains so popular under the circumstances, but it was explained that most of the graduates end up working for banks or government. Governments including our own frequently feel their laws don't apply to themselves.

|

| University of Vilnius |

If you think about it, a country which is attempting to convert from a Soviet colony to a member state of the European Community has a lot of loose ends to tie up. The title to a property is regularly clouded by the experience of confiscation by the government and then subsequently return to a free economy; if banks accept such collateral, there may well be a lot of legal work to be done to assure its security. Since the thirty-odd members of the European Community all have different legal systems in different languages, all banks and businesses which attempt to operate across borders require partners or consultants in law firms in many countries. While there is a continuous effort being made to establish some uniformity of laws in the various nations of the Community, it takes a fair amount of study just to know what the laws are and how they differ. Therefore, while a handful of lawyers are sufficient to appear in court in disputes and litigation, a great deal more legal background is required, just for businesses to know how they are expected to behave.

Since, as Justice Holmes remarked, the life of the law has not been logic, it has been experienced, it emerges that a great deal of effort must be expended to create the logic when there has been no preceding useful experience. The example is offered of American bankruptcy law, which did not exist until Robert Morris forced its creation. Morris had become an enormously wealthy man, and thus created an enormous tower of debts when his speculations failed, amounting to the then-staggering sum of $12 million of debt. They put him in debtors prison on Walnut Street, but that scarcely addressed the real problems of all those creditors tangled up in the mess. Lithuania is in a similar position, and although it has created a bankruptcy law for corporations, there is as yet no bankruptcy law covering individuals, and hence credit cards, etc. are difficult to establish.

There is a notable difference in attitudes between the eastern nations which were former members of the Soviet Union, and are intensely eager to learn more about the evolution of American law, and the more western parts of Europe, where disdain and hostility for American exceptionalism is presently dominant. A moment of reflection about this difference in a situation should make Americans more tolerant of western European problems. If the logic of law evolves out of the contemplation of experience, it may well be easier to begin without any usable experience, than to begin with centuries of experience which has to be re-examined. It must in fact be a wrenching experience, but one which has the potential to teach Americans a great many things we never had to cope with. The eventual outcome should be a healthy one, providing of course that we can keep our tempers, and acquire a little humility along the path.

Going Down with All Flags Flying

They tell me every man is a little afraid of his father-in-law. I was certainly afraid of mine. He was a giant of a man, and no one called him gentle. As a college student at little Hamilton College, he was named to Walter Camp's All-American football team, subsequent to a famous game at West Point. In those days, wearing a helmet was the mark of a sissy, and kicking the opponent in the groin was nothing much. In off-season, he went out for track and field and held the American record for the forty-pound hammer throw for a number of years afterward. Believe me, he was plenty big. As an intern at the old Roosevelt Hospital in New York, he used to volunteer to ride the ambulance into Hell's Kitchen, mostly for the fun of being able to mix into the bathroom fights.

Now, the really intimidating part of his character as far as a nerdy son-in-law was concerned, was intellectual. His roommate at Hamilton had been Alexander Woollcott, the man who came to dinner. My mother-in-law despised Alexander, as apparently, every hostess did. But my father-in-law enjoyed him thoroughly and would invite him to give a lecture at the local Torch Club in Binghamton as a way of showing the local disbelievers just who really knew whom. My in-laws lived in a small city in upstate New York which seemed to me to have invented the concept of provincialism, but I kept my opinion private. My father-in-law felt no need to conceal his opinions, and that too put me in awe. He didn't go around calling his neighbors a bunch of narrow-minded blockheads, but it was definitely true that his favorite expression was, "Well, that comment of yours is ridiculous, of course." As a man who could hold his own at the Algonquin Round Table as well as against the Army offensive line, he said just about anything he pleased.

I truly believe he was an outstanding physician, although I never saw him in action as a physician. He belonged to some of those snotty surgical societies which would be unlikely to admit a man from a small town unless he had more than distinguished himself. Societies like that do have a certain number of dolts in their membership, but such dolts are almost invariably from Harvard or Johns Hopkins or some similar place where being a sycophant to the society president back at home can occasionally get you admitted as a favor to the great man. That sort of thing is unlikely to get someone admitted from a small town unless he is an individual of unusual distinction. Even beyond such honors, I talked medicine with him quite a bit, and I am left with the feeling that he knew what he was talking about. As we say in the medical locker rooms, he was my kind of doctor.

But one day his time was up. He called us to say goodbye, just before he underwent emergency surgery from which he held scant hope of recovery. His surgeon was much more encouraging to us on the telephone, but when we arrived, he told us of the conversation he had conducted with his patient. As nearly as I can recall what he said, it went like this:

" Dr. Blakely, I think you have appendicitis, and we must operate immediately." "Nonsense. I have mesenteric thrombosis and I Know it."

"No, said the surgeon, "I believe you have appendicitis. It's quite typical."

"Will it do any good to operate on me if I have mesenteric thrombosis?"

"No," replied the surgeon. "But I believe you have appendicitis and operation will save your life."

"Now listen here," said my father-in-law, "My own father died of mesenteric thrombosis in 1922. Since that time, I have read everything that was ever written on the subject. Have you?"

"Well, no, I haven't, but I have seen a lot of cases of appendicitis, and I think you ought to be operated on immediately."

The old man looked him hard in the eye and waited a minute. And then quietly said, "Very well."

As anyone can guess from the way I tell the story, he had a mesenteric thrombosis in his belly when the surgeon opened him up. And he was dead before my wife, his new grandson and I arrived to be at the bedside.

Looking Beyond Cheap Oil

It can't hurt if we stop global warming, and probably, in the long run, it will matter more than whether the Jews defeat the Arabs, or vice-versa. However, we won't think so if one or the other blows us up. Timing the sequence means it may be important to settle the terrorist issue, sooner.

Frederick Mason Jones,Jr. 1919-2009

|

| Mason Jones |

Classical music, however else it may be defined, strongly implies music played by an orchestra, or at least a group of musicians. It thus should be no surprise that the members of a famous orchestra bond together for most of their lifetimes in a sense far beyond the ordinary meaning of teamwork. If you are good, really, really good, you will come to the orchestra as a boy, devote every hour of every day to the orchestra, and step down only as a famous old man when you sense that reaction times have slowed. You sit together, travel together, rehearse together, and talk a language of detail which no one else can fully comprehend. Mistakes that one of you made forty years ago in performance, are still joked about because your colleagues know you still feel the pain of it, just as they share their own infrequent but no less fully remembered, moments of failure, largely unnoticed by the audience. When one of your colleagues dies, you turn out by the hundreds for the funeral. And when the hymns are sung, the organist is ignored, struggling to keep up with the people who really know music.

Mason Jones attended the Curtis Institute, itself a collection of prodigies, and was hired by Ormandy after a single audition; a year later he took the position of a first horn and kept it until he finally sensed he was passing his prime and laid it down. He was featured in the many recordings which defined the orchestra, and the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet. He sometimes recorded as a soloist, but he thought of himself as an orchestral horn player, teaching orchestral horn at the Curtis to many generations of aspirants. He even conducted a little, usually in small groups. His comment on that was that it doesn't take much to be a conductor. "Just ask any orchestra player." At his funeral, it was related that the second horn once had two solo passages repeated within a larger piece, but when its time came there was silence. The second time around, it was played faultlessly. Afterward, Mason was asked what happened. "Fell asleep," he answered. And the second time? "I just played it for him."

|

| St. Peter's in the Great Valley |

Mason's funeral was held at St. Peter's in the Great Valley, illustrating that strange combination of artistic prodigies with modest beginnings, and the highest of high society, who mix together to create a great orchestra. A very well-groomed lady was heard to remark that this was where she had her coming-out party. St. Peters was founded as an Anglican mission church in 1700 in the Welsh Barony, built a log cabin church in 1728, replaced it with a little white jewel of a church in 1856, and added new buildings in the past few years to accommodate the population growth in the valley. The church has abundant well-tended land, sited on a hilltop surrounded by high hills, quite suitable for a college or private school campus. The homes in the area are a step beyond splendid, hidden in the wooded countryside. Unless you know precisely where to go, the tangle of country roads will defeat you. But the arterial of U.S. 202 is only a few miles away, and Philadelphia's silicon valley nestles beside the highway, inevitably closing in on the countryside. There will be horses and kennels and fox hunts in the region for another decade perhaps, but the new world is moving in on the old one, from all directions.

The Godfather

|

| Angelo Bruno |

There are people who deny that Philadelphia has any organized crime; and it certainly doesn't have a Mafia. That may be true, but still the rumors do persist. They say in the street that someone named Angelo was once the head of the mob, and that may not be true either. However, it is true that one day he had his head blown off sitting in his car, and it is definitely true that the sidewalks were swept and completely safe for several blocks around his South Philadelphia house. If there was an empty parking space along that block, no one took it.

One day before he met his untimely end, he was a patient on the seventh floor of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and the patient in the next room was a ninety-six-year-old starchy matron, whose faculties were a little impaired, and who had a daughter named Mary Stuart. As commonly happens with old ladies at sundown, one evening the matriarch became a little confused, and shouted out, "Mary Stuart!" After a brief pause, she repeated, "Mary Stuart, Mary Stuart!" This continued for an hour, and finally, Angelo put on his bathrobe and came around to see what was going on next door.

When he appeared at the door, the old lady sat bolt upright and said, "Young man, just who do you think you are?"

Angelo smiled broadly and replied, "Why, I'm Mary Stuart."

Copy of The Godfather 10/11/18 11:09 pm

|

| Angelo Bruno |

There are people who deny that Philadelphia has any organized crime; and it certainly doesn't have a Mafia. That may be their view of it, but still, the rumors do persist. They say in the street that someone named Angelo was once the head of the mob, and that may not be true either. However, it is true that one day he had his head blown off sitting in his car, and it is definitely true that the sidewalks were swept and completely safe for several blocks around his South Philadelphia house. If there was an empty parking space along that block, no one took it.

One day before he met his untimely end, he was a patient on the seventh floor of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and the patient in the next room was a ninety-six-year-old starchy matron, whose faculties were a little impaired, and who had a daughter named Mary Stuart. As commonly happens with old ladies at sundown, one evening the matriarch became a little confused, and shouted out, "Mary Stuart!" After a brief pause, she repeated, "Mary Stuart, Mary Stuart!" This continued for an hour, and finally, Angelo put on his bathrobe and came around to see what was going on next door.

When he appeared at the door, the old lady sat bolt upright and said, "Young man, just who do you think you are?"

Angelo smiled broadly and replied, "Why, I'm Mary Stuart."

COPY of Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, MD 10/11/18 11:22 pm

Working as a woman doctor in the days when women were limited to 10% of the admissions to many colleges, and often excluded entirely, Mary Blakely graduated first in her co-ed class at Binghamton (NY) High School, followed by first in her class at Bryn Mawr College, and the first in her class at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. In fact, she had the highest grades in five years at Bryn Mawr and was selected as a medical intern at the Massachusetts General Hospital, going on to the nation's most prestigious radiology residency under Ross Golden at Presbyterian Hospital in New York, and subsequently with Aubry Hampton. During much of that time, she lived in Philadelphia and commuted on the train to New York. She had married me a year earlier, and the train conductor grew visibly more anxious as she became increasingly pregnant during the several-month commute from Philadelphia's Broad Street Station to Penn Station in New York. Both railroad stations have since been torn down, and the baby she was carrying has been retired for ten years after being Managing Director at Morgan Stanley.

The State of Pennsylvania required a rotating internship, and while I still believe that is the best sort of internship, it was particularly galling to have the reason given that her internship was the reason for refusing to grant her a Pennsylvania license. So she got a job at the Philadelphia Veteran's Hospital, and later at Philadelphia General Hospital, the City's charity hospital of three thousand beds. Well, she never mentioned this Philadelphia affront to a premier academic Boston institution, but I didn't. Perhaps church politics are more vicious still, but this little episode illustrates how very nasty medical politics can get. Perhaps it is a feature of the human personality everywhere, but some situations freely tolerate it, while a few others just don't.

Well, in time she was offered the chairmanship of just about every Radiology department in Philadelphia, and turned them down, saying she didn't want to be chairman of any department. Perhaps she meant any department in Pennsylvania, but she never did make her feelings known. Eventually, she did become Professor of Radiology at Temple University, where she happily taught the residents for many years, during the course of which she was given the Madam Curie Award, the Lindback Award, and various other honors. She had an amazing facility to start dictating reports on x-rays before they were completely out of the envelope and always won the interdepartmental contest for diagnosis of strange films, to the point where other, mostly male, radiologists were afraid to compete with her. She won the Lindback Award for Excellence in Teaching. I used to say I didn't know whether she was any good or not, but I never met a radiologist who wasn't thoroughly intimidated by her ability to make a strange diagnosis at a glance. All her life she got along with five hours of sleep, invariably getting to bed after me and getting up the next morning before I did. Essentially, there were twenty-eight hours in her day.

So it wasn't just radiology where she excelled. Her father once told me there was nothing she could turn her hand to, where she didn't excel. Especially female skills. She was past the point of competing with males and beating them, but female skills were something else. She was a master cook, a demon housekeeper, a champion seamstress, a masterful dinner partner. Athletics were never attempted because she knew very well that men hate to be beaten at golf or tennis. It was the era of Kathryn Hepburn and Grace Kelly, and with a minimum of makeup, she turned heads where ever she went with that Bryn Mawr look about her and her painfully simple clothes. Several of my classmates, usually from Princeton, was struck dumb by her looks. For example, my book editor from Macmillan had a classmate of mine for his doctor. That Park Avenue physician never married and confided to the editor that he had been carrying a torch for her, all his life. It brought to mind the boastful lines from Congreve, in The Way of the World:

"If there be a delight in love, 'Tis when I see, The heart that others bleed for -- bleed for me."

The Philadelphia Delegation to he Pennsylvania Medical Society I

THE PHILADELPHIA DELEGATION TO THE PENNSYLVANIA MEDICAL SOCIETY - I

George Ross Fisher, Chairman

Barbara Shelton, Vice Chairman

During the 1988 meeting of PMS at the Adams Mark Hotel, the Philadelphia delegation directed its chairman to write articles for Philadelphia Medicine, describing delegation activities. Many members of the society do seem to have relatively little idea of the activities of their elected representatives, and perhaps need to know more.

The Republic of Medicine

The best way to describe the medical society "system" is to see it through the eyes of a member who, for whatever reason, becomes actively involved in social activities after a variable time as a relatively passive member. Most newcomers to active participation in "organized medicine" are surprised and pleased by flood of insight into the unexpected brilliance of the creators of the system. The central ideas of organized medicine came from two main two sources, the creators of the national constitution in 1787, and the physician group of 1847 who adapted the national constitutional process into a republic of physicians. Both groups met and conducted their work in Philadelphia. No doubt the similarities between the national constitutional system and the Republic of medicine were increased by meeting in the same city, sometimes in the same buildings. Undoubtedly, successive generations of newcomers to organized medicine are able to navigate its complexities by encountering familiar landmarks of national civics. Conversely, it is frequently a source of continuing pleasure to activists in organized medicine to encounter personal experiences which evoke the enduring insights of the founding fathers of 1787.

The Electoral System

Organized medicine, like the United States of America, is not a democracy, it is a republic. What does that mean? It means that all the voting members of county medical societies are periodically asked to select colleagues to represent them. Once elected, those representatives are trusted to make decisions about specific issues on behalf of the members, and those decisions are subsequently binding on society. The general membership generally selects representatives of their own style of thinking, and eventually replace representative's who prove disappointing. The membership makes their views known to their representative is fully delegated to hear the debate and use his best judgment on behalf of those who elected him. In Pennsylvania, delegates each represent about a hundred members of the county society, although in New Jersey there is a delegate for every ten members. In California, local groupings of physicians select their own specific representatives. In Pennsylvania by contrast, the members of each county-wide vote. Collectively, those delegates become the Pennsylvania Medical Society House of Delegates collectively select about one-tenth of their number to become delegates to the American Medical Society. Since few medical issues markedly separate Pennsylvania's viewpoint from that of the rest of the country, delegates originating in Pennsylvania are representative of the profession as a whole more than they are agents of local faction. Similarly, few issues before the Pennsylvania House of Delegates evoke a special Philadelphia viewpoint.

From this overview it can be seen that any physician who wants to be presidents of the American Medical Association need only persuade a few of his friends to vote for him as a delegate to the State Society, then persuade about a hundred of his fellow delegates to make him a AMA delegate, and subsequently persuade 201 of the other AMA delegates to elect him president. Many doctors from Philadelphia have climbed this ladder, and every doctor who reads this article could potentially do so. Of course, it turns out to be a more difficult path to follow than to describe, but perhaps this oversimplified description will serve to illustrate the vital essence of a republic: selection of representatives at each step is always in the hands of a small group of electors with opportunity to know the qualities of candidates intimately. No television "sound bites", newspaper posturing, or demagoguery from a podium will elect someone well known to the small group of peers who cast the ballots. No candidate within such small groups can long conceal major personality flaws or biases from the group. Sometimes someone claims the leadership of medicine does not reflect the viewpoint of the rank and file; it is hard to see why that should ever be so.

The Republic of organized medicine derives from elegant design, but it contains one potentially serious flaw at the very beginning step of the process of election. The individual physician members of many country societies mostly do not cast their ballots. From many conversations with members, it is clear that the main source of failure to cast votes s not indifference or inertia, but rather a fear that lack of information will inadvertently lead to a vote for the wrong candidate. A system which was consciously designed to assure that voters really knew the delegates for whom they were voting can thus sometimes fail because a high conservation electorate fears that its information is inadequate. All information is only partial, but the individual physician's assessment of the fellow members of his hospital staff or neighborhood is surely superior to the knowledge available to voters in any other sort of election it is possible to name. The society can be positively assured that the scrutiny of candidates once they become active in organized medicine is intense, but it is entirely up to the membership to be serious about choosing local captains.

The Caucus System

Historians relate that the founding fathers of the American Republic did not anticipate the development of the party system, which was largely the creation of Martin Van Buren. That is, the founding fathers did not anticipate that coalitions would form among voters with enduring special interests related to geography. The Republic of medicine has never developed a party system, presumably because the members of a single profession have fewer reasons to polarize for more than a vote or two. Coalitions definitely do form, but seldom endure for more than a year or two before some other issue causes new coalitions to reorganize. However, the large volume of business creates a need for small discussion groups, and group efforts are required to promote the election of officers of a profession which unite and inflame the passions of a geographical locality against some other region or locality. Mostly, however, state and regional caucuses are study and discussion groups, social clubs, and mechanisms for promoting the election of members who are wise enough to know that intense personal ambition is not a highly regarded quality. Although passionate love of your hometown is a faintly ridiculous component of a professional scientific society, there can be little doubt that the local caucuses operate to the advantage of the profession by identifying and encouraging useful leaders who might otherwise be too diffident or awkward to succeed on their own. By promoting its obligated members to leadership positions, the caucus puts its stamp on policy; the reelection process then ensures that those in leadership positions will return to their grassroots with information about "inside" activity. Caucuses provide instruction for newcomers, an opportunity for young delegates to select informal mentors at the breakfast tables. And caucuses give some entertaining parties, which greatly relieve the tedium of a great volume of detailed professional business.

The Reference Committee System

Reference Committee are a particular invention of organized medicine. They are not to be found in the United States Congress, or in Thomas Jefferson's American modification of the rules of the British Parliament, or in the famous rules of order written by General Roberts. The inventor of reference committees at some early House of Delegates of the American Medical Association is apparently not discoverable, but the high priestess of parliamentary process today within organized medicine is Mrs. Sturgis. Her book describes the process of the speaker of the House convening select member committees to review privately the complexities and merits of business before the House, capsulize their opinion, and present it before the fully assembled House as respected advice for general consideration in the debate. Her book also leads the parliamentarian or the speaker around most of the traps and inconsistencies which have surfaced during decades of use, setting sensible rules which mainly allow the assemblage to avoid entanglement in its own processes.

The reference committee system is essential if we are to preserve the right of every member to submit his complaints, suggestions, and resolutions to any meeting of the House of Delegates. The system makes it possible for any member of the society or invited guest to deliver written testimony, or to speak before a microphone without any time limitation. At the same time, the reference committee system makes it possible for a House of Delegates to vote as a whole on several hundred issues in a session, and to be satisfied that their votes were informed ones.

Different speakers have different views about the composition of a reference committee; and different houses of delegates have differing traditions. Currently, the American Medical Association follows the traditions of assigning each member of the House to reference committee in rotation, a system which places a member on a reference committee every eight or ten sessions. An effort is made to assign members to a committee covering subject material with which he is not strongly identified, and hence is likely to give neutral impartial opinion. At the Pennsylvania Medical Society House of Delegates, there has been a tendency to pick reference committee members with a great deal of expertise in the subject under discussion. There is something positive to be said about both approaches. There is nothing sacred about the opinions of the reference committee, and many of their recommendations are swept aside by the House. Consequently, a reference committee chairman quickly develops the goal of providing advice which he believes the House will accept, thereby avoiding the embarrassment of a snub. The reference committee system is to some extent an elegant mechanism for harnessing the egotism of the committee members to the goal of reducing unnecessary floor discussion and quickly achieving the will of the House. Those who are ignorant of Mrs. Sturgis' rules quickly find the pace of business leaves them and their favorite projects behind.

The AMA has the perfect vehicle for defining the quality of care in a particular situation, the PRO system has the people on the front line, observing the gray areas and problem areas. The overlap delegates Weeks, Pierson, Eberle should hustle up the others to forward a stream of requests to AMA to study particular areas. The outcome should be that the collected works of CSA would become the de facto standard for quality.

Subject: Washington Fellowships for Doctors

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation supports six fellows in health care each year; Allen Hyman was one. The PMS or AMA ought to establish an office for locating suitable candidates and finding fellowships for them. Roger Egeberg suggested as his person. Cost limited to the expense of putting the deal together; the fellowship money to come from foundations. White House fellows, Johnson fellows, Pew fellows, etc.

Lay Oversight of Physician Orders in Intermediate Care Facilities

Whereas, federal regulations concerning intermediate care facilities (400.150) specify (E),(2) that drugs for the control of inappropriate behavior must be approved by the interdisciplinary team.

And Whereas, regulations (483.440) specify that (C),(1) each "client" must have an individual program plan developed by an interdisciplinary team which represents the "professions, disciplines or service area which are relevant".

And Whereas, the statute and regulations (1801) declare that "Federal interference with the practice of medicine is prohibited".

Therefore be it resolved that the AMA study all sections of the Social Security Act which utilize the word "client" in a medical setting where the term "patient" might equally apply, seeking to determine whether some regulatory provisions promote interference with the practice of medicine.

How to Cope with a Trillion Dollars of your own Money.

"Eighty years ago any one of the 'tycoons,' whether in the U.S, Imperial Germany, Edwardian England or in the France of the Third Republic, could and did by himself supply the entire capital needed by a major industry of its country. Today the wealth of America's one thousand richest people, taken together, would barely cover one week of one country's capital needs. The only true 'capitalists' in developed countries today are the wage earners through their pension funds and mutual funds." (Peter F. Drucker, The Wall Street Journal, September 29, 1987.)

In the passage displayed above, a noted authority on the American economy has concisely captured the new dimensions of capitalism in the Twentieth Century, even though his jump in logic can be disputed. It is too soon for the evolution from Nineteenth-Century tycoons into universal capitalism to have affected common parlance; redefinition took place without anyone's planning or prediction. People who describe themselves as workers and employees are slow to develop attitudes and skills appropriate to their new economic power. It is equally uncongenial for those who think of themselves as entrepreneurs and managers to accept "people's capitalism" as the present and growing future of free-enterprise America. Drucker's partitioning of the country into two classes may well be disputed, but he has an insight of some sort which warrants examination. Obsolete class rhetoric will doubtless persist through several more presidential election campaigns.

Two things fit together here. It takes a ton of money to finance a multi-trillion a year economy. It also takes a ton of money to pay for a whole country to retire from work at age 65 and then go on a twenty-year vacation. The new imperative of capitalism is that we somehow must save enough of our collective working income to supply the capital requirements of the economy, which must, in turn, employ such capital efficiently enough to pay for our old age including its inherently heavy medical costs. If we have wars we will have to pay for them too, but the main dividend of our economy does go into a national retirement nest-egg. That's why we work, and that's all we have when we are done working. Stop worrying about quick-rich stories like Mr. Boesky's concerning conspicuous consumption by overpaid yuppies on Wall Street. Forget about the occasional person who takes a year or two off in mid-career to wander around Nepal. Don't however forget to remember the poor, the disadvantaged and the shiftless, because they get old too, and are part of the molten mass. In my view, the national economy can be roughly summarized as a process in which we collectively attempt to have nearly everyone spend his last cent on the day he dies but not a day sooner, living as well as he can in the meantime. Within the scope of this description we thus all become capitalists as we strive to enjoy twenty years without working income after we retire. The only alternative is that we mustn't live so long.

Because broad-based or near-universal capitalism has evolved recently and is not entirely acknowledged, the present system has some large transitional defects. Health insurance, unfunded health insurance, is one of the main defects we will get to in a few pages. A more immediate structural defect is what is that we have not yet evolved an efficient system of aggregating the savings of a nation of little capitalists who are unsophisticated in the ways of Wall Street and want to stay that way. Not only does it cost excessively to hire investment advice, but the voting power of ownership control gets lost in the process.

In the bad old days, when J.P. Morgan and others would buy common voting stock, they bought the company, and the company certainly knew it had been bought. If all of the officers and managers of the bought company weren't soon changed, that was only because they made desperately clear they were ready to take orders about company policy. By contrast, when T. Boone Pickens today buys a similar share of the voting stock of a corporation, the hired hands appear before a congressional committee, or the legislature of Delaware, to get a law passed outlawing the "unfriendly takeover". In Morgan's day, money didn't just talk, it screamed. Today, well, money is in a fight for its life with one-man-one-vote power in the hands of elected representatives. People's capitalism has become a humbled passive investment process, although not necessarily a cheap one, or invariably profitable.

There may be some exceptions, but the middlemen in peoples capitalism have generally declined to grab the voting power which the small stockholder cannot usefully exercise. The people who run what is known as the "Institutions" are custodians of great gobs of other people money in a mutual fund, pension or insurance trusts, and hence hold enormous voting power in the election of corporate directors, officers, and auditors. For some reason institutional investors seldom vote against the management, generally preferring to sell the stock if they are dissatisfied with the way things are going in a portfolio company. Consequently, the entrenched management of major publicly held corporation can do just about as it pleases even following policy disasters. To say this is a flaw in our system is a massive understatement. Things which run by the law of gravity generally tend to go in only one direction. No one wants to see the Japanese pulverize our major corporate jewels, no one wants to see them repeatedly greenmail. Nobody loves a corporate raider.

And still, it is clear the little stockholder cannot and never will aspire to meaningful voting power in a corporation which has millions of shares and thousands of stockholders. (Footnote; When I get those expensively packages proxy cards for my pitiful holdings, I always vote along with management. My theory is it's a good thing to change watch dogs frequently, and my Quixotic vote might hurt somebody's feelings enough to notice the message it sends). The system of governance of very large corporations needs to be reformed by its insiders before consumer activists using one approach, or elected public officials using another, manage to fill the power vacuum to our national disadvantage. They might, for example, reexamine the New York Stock Exchange rule, prohibiting the listing of companies with more than one class of stock. Someone should be asked to evaluate the experience of companies like Ford which evaded the rule, or of those companies which escaped to other exchanges to avoid it.

The directions such reform might take are not the concern of this book; the present focus is on the difficulties which are created for pre-funded health insurance by the fact that corporate voting power materializes whenever major purchases of common stock are made for purely investment purposes. Unpredictable things happen no matter how the stock is voted. If the voting power in the hands of custodians is never exercised, corporate control automatically concentrates in the hands of those whose ownership is relatively minor, whether insiders or outsiders.

One does not have to be a rabid conservative to recognize that government ownership of voting control of a corporation is a form of is w form of nationalization. The Labor party in England nationalized the steel and airline industries, the Socialists in France and India nationalized the banks, Communist doctrines go to the extreme of requiring government ownership of the total "means of production". If we are imaging success in the effort to pre-fund a trillion dollars of health insurance, we have to contemplate the highly undesirable features of potential government control of the voting stock of IBM, American Telephone and Telegraph, Exxon, and Morgan Guaranty Bank. The aggregate worth of all he stock on the New York Exchange is xx xxx. A trillion dollar worth of all the stock implies voting control of quite a bit of corporate America, no matter how sincerely its managers try to avoid it. a resolutely passive investment stance would just make it cheaper for the Japanese to buy control or for that matter the Russians, if they wanted to do it.

This scary line of thought potentially leads to the conclusion that pre-funded health insurance should avoid the purchase of common stock. But that seems bizarre; the historical difference between a 3% return (bonds) and 8% return (stocks) means this voting control issue could condemn health insurance pre-funding to a pitiful fraction of its potential for reducing the costs of an essential social service. It seems imperative to seek ways to improve the long-term return, even if government-controlled pools have to be rejected. True, massive increases in the proportion of non-voting stock confer unwarranted power to the management of the corporations and their potential greenmailers, no matter who runs the passive investment pool. Go one long jump beyond that; they just cannot be permitted.

As a matter of fact, it is impossible to conceive of a permissible investment vehicle for a government-controlled fund, except government bonds. Unfortunately, when you look at what has happened to the Social Security trust funds which are totally invested in government bonds, you find an appalling thing. Buying government bonds isn't too satisfactory, either.

When sums approaching a trillion dollars are involved, even the finances of the United States Government must reckon with the law of supply and demand. If a lot of people want to buy government bonds, they push the price up as long as the supply is limited. Since government bonds are issued to pay for federal debt, increasing the supply of those bonds means increasing the national debt, so we ordinarily don't want to do that either. That is, we don't want the Treasury to issue more bonds just to provide a safe investment vehicle for funded health insurance. On the other hand, by restricting permissible investment to government bonds in huge amounts we cripple the cost reduction of health insurance, since the inevitable result of clamoring to buy bonds will be lower interest rates. Quite aside from the fact that a captive customer gets shabby treatment, it may not be in the national interest to lower interest rates. Since Government bonds are regarded as the safest possible investment, their rate is the floor under all interest rates in the country or even the world. So, lower interest rates are inflationary, even at times when it may be contrary to national policy to stimulate inflation.

What this focus on government bonds has stumbled onto is the mechanism by which modern government attempt to fine-tune the national economy, a process mostly devised by the British economist Maynard Keynes. Based on the premise that no one controls enough money to affect the market price of government bonds, the government sets the price by buying and selling to itself. This particular conflict of interest operates between the Treasury which issues the bonds, and the Federal reserves which buy them. To a certain extent, the Arabs and the Japanese have been rich enough to influence the price of US Bonds, but the largest "external" bond buyer has been the Social Security trust funds. The quasi-external quality of the trust funds is often minimized or exaggerated as it suits some momentary purpose. If more money flows into the funds from tax payments than flows out for pension checks, the trust funds are described as assisting the national deficit. However, if the future indebtedness of the funds is increased more than current revenues are, this debt is regarded as the trust funds' problem and not a matter of national accounts. All this is a cross-generational difference in point of view. My generation can only see it as one big sticky ball of wax. The Federal Reserve's regards it as a major obstacle to their effective use of Keynesian principles. One has to conclude that it would be very unfortunate to add a great big lump of health insurance funding to a government bond problem which will be convulsive enough without it.

In summary, what can we conclude about investing the proceeds of funded health insurance, if we could ever get around to funding it? We see that the creation of a new source of investment capital would be an enormous asset for the national economy, but reckless dumping of huge amounts of cash in any market at all could be disruptive. The purchase of common stock would be considerably more cost-effective than buying bonds, and in the long run, might even be safer. However, equity markets need to consider how to cope with the continuous concentration of voting control of major corporations by default, as a majority of votes would become further locked into passive custodial accounts by funded health insurance. And finally, control of funded health insurance by government agencies poses the same problem of stock voting power which is left to Wall Street to solve, the next chapter tries to consolidate these issues into a general prescription. Remember, Index fund investing is momentum investing. If everyone does it at once, it will pop the bubble.

Four Prescriptions: Proposals or Reform of Health care Financing Rx. I: PRE-FUNDED HEALTH INSURANCE

The Chicago Quartet Volume Two

Four Prescriptions: Proposals or Reform of Health care Financing

Rx. I: PRE-FUNDED HEALTH INSURANCE

INTRO page 1.

Introduction

Benjamin Franklin organized the first American fire insurance company in 1736. Success in the insurance business rests almost unnoticed among the many scientific and political accomplishments of that remarkable man. Even in Philadelphia, few people realize Franklin’s company and several others like it still operate comfortably. Franklin called his company a “Contribution shipâ€, but a more familiar modern term is “mutual†insurance company. Even though mutual life insurance companies have come to predominate, for important reasons fire insurance has been more salable when provided by profit-making companies. The ancient mutual fire insurance companies remain small but reflect some important thinking which this book argues should be applied to health insurance, where ideas are currently badly needed.

What the world already knows about these quaint little companies is almost a hindrance. Occasional articles in the Philadelphia Sunday supplements do sometimes mention them, mostly fascinated with how socially prestigious it is to be a member of their boards of directors, what excellent dinners are served at directors meetings, what priceless antiques are to be found in their headquarters. Franklin to be sure would probably relish the elegance. Unlike the Quakers of Colonial Philadelphia, Poor Richard was not frugal in order to be inoffensive; he was frugal to get rich. Dying the second richest man in the city, he lived the kind of life many Yippies might admire.

Mutual fire insurance companies sell something called "perpetual insurance" which turns out to be perfectly ordinary homeowner's insurance, with one big twist to it. The customer makes one large lump sum deposit in advance, then never pays premiums. During all the time the insurance is in force, perpetually if need be, no further premiums are paid. The deposit earns enough interest to pay the full premium cost of the insurance protection. In that way, the customer has the perfectly astounding experience of having every penny he paid to the company returned when he eventually gives up the insurance. Centuries of experience show that a single deposit of roughly ten years conventional premium will generate enough investment income to cover all anticipated costs from "losses" and administration. The deposits themselves "share the risk", eliminating the cost of paying investors to provide a "contingency reserve". This simple scheme is Perpetual mutual insurance.

As everyone knows, that isn't the way most fire insurance works; the only things perpetual about a more typical policy are the yearly premium notices, which in the aggregate eventually cost much more than making a deposit and giving up the income from it. It is left to the typical stockholder company to worry about getting contingency reserves coming from investors are more popular with homeowners than reserves they have to provide themselves, consequently why perpetual premiums are so much more scalable than perpetual insurance. The young homeowners is typically a debtor, stretching to buy the best house he can afford when he can stump up a down-payment; fire insurance is something his mortgage banker insists he buys. In order to have the American dream a little earlier, the homeowner agrees to pay a little more, later.

Two hundred years after Franklin's death it is possible to gain other insights from "perpetual" insurance because the unfamiliar approach makes us ask basic questions. The next several chapters of this book now set out to argue that health insurance has some serious problems which could be improved by asking those questions. The problems of health insurance are not trivial; many experts question whether we can afford to continue the present system. Whether a breakdown of health insurance would lead to worse care, no access to care or rationed care, the whole subject of health insurance is important to more people than insurance executives. We will return to Franklin's idea after a flyover of current major problems of health insurance, with reflections on how things got to be such a mess. Then, after compounding several insurance remedies based on Franklin's formula, an effort is made to identify potential harmful effects but few are found. The main problem with the prescription is that it has a rather bitter taste.

WHAT'S WRONG WITH HEALTH INSURANCE

There are many things good about the American system of health insurance. Compared with the nationalized health insurance schemes of other countries, our health insurance is a utopia. Indeed, the main reason to criticize the American system of health insurance is to save it from itself, since the foreign alternatives are so much worse. No doctor ever saved a patient by ignoring the symptoms. To be concise, our health insurance system is unfunded, inappropriately linked to employment, adequate for moderate illness but not for catastrophic ones, and incredibly expensive to run. For each of these four disorders, this book offers a prescription. In the first section, keeping Poor Richard in mind, the disorder under examination is that health insurance is unfounded. For the ailment of being unfunded, the prescription offered is the IRA for Health.

Unfunded, Being unfunded does not mean cheap. It costs a typical family about $3500 a year for health insurance premiums. It has become commonplace to read newspaper articles announcing or predicting 15-30% increases. Annual national costs of healthcare are about $500 billion. Those who would like to solve the problem with a national health scheme should remember that $500 billion would be half of the current Federal budget; the $200 billion already federalized are nearly destroying the government. Health care is expensive all right, and unfunded.

Further, because an employee can escape income taxation on a health insurance premium if his employer pays it for him, that's the way health insurance.

One More Idea, Please

The 1975 annual meeting of the Association of foundations for Medical Care was, as usual, a provocative and informative forum for mutual exchange of ideas. An entire day was devoted to exploring the problems which need to be solved in order to get an Independent Practice Association off the ground and solvent. How do you attract subscribers? How do you enlist the support of physicians?

One disturbing problem was not resolved, however, and the failure even to discuss possible solutions seems even more disturbing to me. That problem is this: what mechanism will be devised to set fair medical fees if your IPA should be so successful that it enlists every physician and sells every subscriber? That is, how do you anticipate the problems of a monopoly? While it is understandable that the potential problems of success are swept aside at a time when the immediate problem is to achieve a viable toe hold, it would be tragic to allow the time of formative philosophy to pass without the setting of goals.

Our fees are now set by the marketplace. As Adam Smith remarked, if you charge too much you lose to your competitors, and if you charge too little you will go bankrupt. The price of everything, Adam Smith said, is therefore always fair and right in a freely competitive market place. The fees of an insurance mechanism are therefore also fair and right if they are "usual and customary". The strong implication of that little phrase is that somewhat a competitive market exists as a standard.

In Pennsylvania we are peculiarly in a position to see what happens when a good hearted idea like Blue Shield becomes so successful that the market place disappears. What happens when you destroy the marketplace is that fees are set by committees, later demand to be a majority of the committee, and eventually demand to exclude physicians from the committees entirely on the argument that the foxes should not be watching the hen house. Frustrated by skillful insistence on charter and by-laws, such customer groups then resort to a different approach: They apply political pressure on the Insurance Commissioner to deny permission for premium increases. This whole process can be summarized as substituting the political process for the market mechanism. There are, after all, more patients than doctors, and this distortion of the marketplace inevitably leads to downward pressure on fees. If you accept Adam Smith's dictum that fees set by the market mechanism must have been fair, it follows that this whole shift leads to fees which must be unfairly low.

Well what do we do about this? First, let us acknowledge one left-handed fairness to it. It is very noticeable that there is no movement at all for IPA's are concentrated in the medically overserved areas because they almost invariably develop as an opposite reaction to closed-panel group practices in their areas. The whole pre-API movement has a suspicious look about it of having no genuine concern about pre-payment, but rather the motivations of a consumer cooperative movement. It is hard to know what to think of this. It certainly does add a disincentive to practice in overserved areas, and probably causes a certain number of outraged physicians to migrate to underserved areas. However, to the extent that physicians are willing to accept less income in order to have the other advantages of living in the suburbs, it can be expected that the total cost to the overserved community will remain the same or rise if the physicians surplus is reduced. Therefore, in the long run, the effort of starting HMOs is self-defeating financially except for those consumer power groups who can take special opportunities for themselves. The other less forward consumers will find themselves with fewer physicians availability, at higher costs.

To return to the problem of preserving a market mechanism for the establishment of fees, several ideas seem worth considering:

1. Limit the market penetration of any group to 20% of the market in its area.

2. Require that no group may exceed a 10% market penetration unless at least four other groups are genuinely competing with it.

3. Identify one whole specialty of medicine as excluded from the "total" coverage of the insurance plan, and use this free-enterprise specialty as a reference group for fees of other specialties. The relative value system would expand from this base.

4. Never start an IPA unless a closed-panel program exists in the area.

There are a number of unpleasant or demonstrably ineffective measurer which could be tried.

5. Limit physician income to a "reasonable" level.

6. Deductible and coinsurance.

THREE WAYS TO ACHIEVE FUNDED HEALTH INSURANCE

Since everybody would benefit if the country found a way to pre-fund health insurance, what options are available or doing so? Or put another way, what obstacles, objections, and vested interests obstruct each possible way of doing it; how difficult would it be to overcome them?

Three general approaches might work reincarnation of Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) .for this special purpose, the legal encouragement of health insurance companies to sell permanent insurance or the creation of a national trust fund. Each of these approaches will now be changed to make them possible. All of them must somehow overcome the main problem inherent in payment in advance, which is that people must find spare money somewhere. while of course the disposable income could be found by reducing expenditures for non-essential luxuries, this discussion limits itself to examining how seed money might be squeezed out of inefficient practices in the existing health financing system.

Health Banking The first approach to be examined has been known by several names. When Michael J. Smith of Louisiana proposed it, he called it the CHIP proposal (Consumer's Health Investment Plan). When John McClaughry and I independently proposed something similar, it was called the Health Protection Account, Peter J. Ferrara of the Cato Institute, who likewise got the idea independently, had the genius to call it the IRA for Health. The IRA for Health has the great beauty that the title itself does most of the explaining; most people know what an IRA is, or was. An IRA for Health is obviously an IRA whose use is limited to health care costs. Unfortunately, congressman, whose cooperation is vital to the success of the idea, have gone through the experience of repealing the tax exemption of IRA's trying to reduce the national budget deficit. Congressmen have the mindset that IRAs will worsen the deficit, or at least that their constituents might think so. It isn't a correct perception, but the catchy H-IRA title has become a hindrance and must be replaced. Health Banking is here offered as a substitute title for Health Iras because it suggests an interest group who might assist the process of public persuasion because they would benefit from it. The definition of what constitutes a bank is in the process of change; perhaps there is room for health banking in some future compromise revision of the Glass-Steagall Act. For example, the mutual fund industry could become interested in health banking as part of their vision of non-bank banking. Perhaps the moribund savings banks could be entrusted with a trillion-dollar consolation for their regulation-induced troubles.