1 Volumes

The Society of Friends

New volume 2019-05-23 17:20:54 description

Interesting Quaker Characters

All alike, but all different.

William Penn, Excellent Lawyer, Terrible Businessman

Richard Dunn, who with his wife Mary Maples Dunn stand as the two core authorities on the life of William Penn, merely smiles when asked to describe what Penn was really all about. "What we need is to have one good biography emerge," said he, "but it isn't easy to guess what it will say". For the present, let's just sketch a few paradoxes which somehow need threading together.

|

| Richard Dunn |

In the first place, the wealth of William Penn can only be described as prodigious. His father had played a central role in restoring the Stuart monarchs, and in the course of it had conquered for the Crown the enormously valuable property of the Island of Jamaica. For these efforts, the father had been rewarded with extensive properties in Ireland and a highly influential position at Court. To all of this was overgenerously added as debt repayment, the American territories which have now become the states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Actual ownership of some of this was shared with others, but all of it was quite effectively controlled by young William. No one else stands even close as the largest private landholder in American history. But to appreciate the immensity of his wealth, it should be understood that he treated this property as a sort of hobby. Over the course of his lifetime, the colonies lost money, and Penn subsidized them rather seriously from his other assets.

At the same time, Penn lived vastly beyond his income in ordinary ways, becoming heavily indebted, eventually going to debtor's prison. It probably was not necessary; his sons renounced Quakerism and made a profit on the colonies after they inherited them. Although he could display remarkable organizational talent, particularly in the organization of New Jersey, his management was mostly slack, his judgment of agents often proved too trusting, and he permitted himself to be exploited by poorly-designed contracts to his eventual financial ruin. Even that might not have been serious; he displayed a towering legal mind in the devising of the doctrine of jury nullification and was the winner in a great many lawsuits. He even demonstrated he was capable of winning dubious lawsuits, soundly defeating Lord Baltimore in a border dispute over Maryland which others have said showed Baltimore had the stronger case. We know he had influence at Court, and such legal victories suggest he might on occasion have taken full advantage of it.

|

| Gulielma Maria Springett Penn |

From the sound of things, some have concluded Penn was so rich and powerful he grew careless about his own best interests, which essentially needed very little defense. In particular, he gave this impression to his fellow Quakers, who concluded he did not need nor likely would stoop to collecting what he was owed in taxes and property sales. This cavalier attitude encouraged the early Quaker merchants to follow their own advantage without shame, and as it happened with great vigor. The Constitutions he devised for the colonies are frequently cited as the brilliant cornerstones of fairness and stability, ultimately the models for much of our present Constitution. Penn really was sincere in wanting to provide a better life for the working people than they could have at home in England. But in the Seventeenth Century, the modest role he devised for the Proprietor commanded little respect and was not one his aggressive clients would have chosen for themselves in his position. Perhaps the most generous description of their passive aggression would be that he taught power and governance to be the collective possession of the whole Quaker meeting, so the leaders of the meeting simply took him at his word. For their part, there can be little doubt of their commercial talents; trade and industry immediately thrived in the colony. However, sharp, aggressive trade and commerce were not things a gentleman would himself want to associate with.

Unfortunately, the historical records of the early colonies are not good; for the most part, we have to surmise the struggles and frictions between a rich, financially careless, and sincerely earnest theologian in his contention with a group of poorly educated strivers who had been told he regarded each of them to be his equal. As the saying goes, he was rich beyond denying. And therefore, he was probably arrogant beyond his own ability to see it as a flaw.

Equal before the law, perhaps, and equal in the prayers of First-day Meeting. But everything about his upbringing, his social circle in London, and his staggering wealth suggested that even a saint would have trouble believing, deep in his heart, that these were truly his equals. And even if perchance he did believe it, they would not have believed it for a moment, had their positions been reversed. Penn certainly acted as though he believed in religious freedom, serene in the idea that if every person earnestly thought hard about ethical issues, everyone would eventually reach about the same conclusion. The elders of the meeting, however, behaved in ways which suggested they would personally prefer non-Quakers to settle somewhere else, and given half a chance would create Quakerism as an established church. There seemed to be those who felt that Friend William was perhaps a little too trusting. And anyway there were some obvious paradoxes. William Penn kept personal slaves.

|

| Hannah Callowhill Penn |

With two wives, William Penn had thirteen children. Among them was considerable diversity of opinion, along with the same tendency to rebellion found in any two generations. Early illnesses and chance led to the emergence of those children who renounced Quakerism and showed no shame at all about wanting to have money in order to spend it recklessly. One would have supposed that a man of Penn's intellectual stature would have been able to control his family better, but his own reckless youth had been so extreme that he had few arguments available when, as seems virtually certain, rebellious children defended themselves by reminding him of his own indiscretions. William Penn displayed absolutely no sense of humor; a touch of it would have been useful in mastering a family and friends who were undoubtedly having a little trouble knowing what to make of this apparition in their midst. Some equally pompous Pennsylvania merchants might have had difficulty denying that in their passive aggression, they occasionally resembled the spoiled brats with whom he found he had ample family association.

REFERENCES

| Remember William Penn, 1644-1944: A Tercentenary Memorial : Edward Martin: ISBN-13: 978-1258369934 | Amazon |

Tom Paine: Rabble-Rousing Quaker?

|

| Thomas Paine |

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was born of Quaker parents, which makes him a "birthright" Quaker. Children born into Quaker families are accustomed to the subtleties of speech and behavior of that religious sect, ultimately growing up to be the main nucleus of tradition. Knowing what they are getting into, however, they are more likely to rebel against it than others who, coming to the religion by choice rather than by birthright, are commonly described as "Convinced Friends."

These stereotypes may or may not explain some of Tom Paine's paradoxes. He certainly was not a pacifist, a quietest, or a plain person. He was an important historical figure; Walter A. McDougall, the famous University of Pennsylvania historian, feels the American colonists might have sputtered and complained about Royal rule for decades, except for Paine. The American Revolution happened when it happened because Tom Paine stirred up a storm.

|

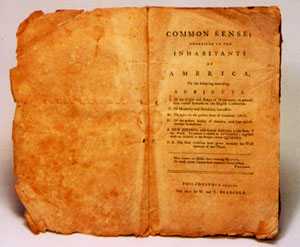

| Common Sense |

According to the traditional way of telling his story, Tom Paine was a ne'er do well failure in London. He ran into Benjamin Franklin, who advised him to emigrate to America in 1775, and within a year his pamphlet called ""Common Sense"" had sold 150,000 copies (some even claim 500,000), galvanizing the public and the Continental Congress into action on July 4, 1776. George Washington read Paine's writings to his troops on the eve of the Battle of Trenton. After that, Paine got mixed up with the French Revolution, and apparently became a severe alcoholic, proclaiming atheism all the way. Although Thomas Jefferson remained friendly to the end, Benjamin Franklin essentially told him to go leave him alone, and Washington would cross the street to avoid him. According to the usual line, Tom Paine was a big-mouthed rabble-rouser and a drunk, who traveled the world looking to stir up revolutions.

However, that cannot possibly be a fair recounting of the whole story. Thomas Alva Edison, whose opinion certainly counts for something, regarded Tom Paine as one of the greatest American inventors, creating the first steel bridge, the first hollow candle, and the principle of central drought in heating. Paine early became a close friend of the Hicks family, the central figures in modern Quakerism; it seems a little unclear how much Tom Paine was reflecting the views of Elias Hicks, and how much Hick site Quakerism can be said to have originated in the thinking of Thomas Paine. Paine was very far from being an atheist. In fact, both he and Hicks believed so fervently in the universality of God that both of them scorned the rituals, paraphernalia, and transparent superstitions of -- religion.

Furthermore, Paine was able to reach the rationalists of The Enlightenment with arguments which cut to the heart of Royalist loyalties. America was too big and too remote to be ruled by a king, particularly one who abused his privileges behind a claim of divine right. William the Conqueror, for example, never denied he was a usurper. One way or another, every king must earn his throne. So, as for feudalism and hereditary aristocracy, what was King George doing with all those German mercenaries? After two centuries of democracy, most Americans are too far from feudalism to appreciate the legitimacy of military meritocracy. Whatever King George was up to, he didn't stand for empowerment of the best and the brightest Englishmen, who in fact might well be opposed to him. If you wanted to get to Virginia aristocrats, Boston sea captains, and Kentucky backwoodsmen, that was exactly the line to take in Common Sense.

Unfortunately, Citizen Tom Paine was a freethinker and couldn't be quiet about it in his later books. He didn't like the way the Old Testament Hebrews hungered for a king. He didn't like the way the New Testament sprinkled miracles on top of unassailable moral principles, and he particularly didn't like the claim that God got an unmarried girl pregnant. He antagonized almost every established religion by proclaiming that no one should make a living from religion. He wrote a book called Age of Reason proclaiming all these freethinking ideas, which struck Ben Franklin as such a stupid thing to do that he would not discuss it, beyond saying that even if he should succeed in convincing people to abandon religion, just imagine how much worse they would probably behave without it. George Washington, who hadn't a trace of intellectualism about him, more accurately portrayed the typical American revulsion at anyone who was so unprincipled as to say such unorthodox things in public. Jefferson distanced himself for political reasons rather than intellectual ones. Franklin thought Paine was a fool. Washington and the rest of the country thought he was a viper.

It would have to be conceded -- by anyone -- that Tom Paine was self-destructive, even sassing Robespierre while in a French prison. How is it such a loose cannon could get the American public off dead center and make the Continental Congress grasp the nettle of revolution, in less than a year? Let's go back to how he came to America in the first place. Franklin sent him.

Then he promptly got a job as editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette, which Franklin had owned for thirty years. And then, in an era when the largest city in America had a population of twenty-five thousand, and the printing presses of the day were able to turn out three or four pages a minute, he sold 150,000 copies of the fifty-page "Common Sense." Who but Franklin, in private partnerships with sixty printers, could have possibly authorized, financed, and printed 150,000 copies of a colonial pamphlet? In order to find that much printing capacity in colonial America, a great deal of other printing had to lose its place in the queue.

Even today, a best-seller is defined as a book that sells 50,000 copies, and it generally takes three years to get it done. In the Eighteenth Century, for an unknown alcoholic to get off the boat and find a publisher for a best seller in a few weeks is hard even to imagine. Unless he had important help.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

Edward Hicks: Peaceable Kingdoms

|

| Peaceable Kingdoms |

Edward Hicks (1780-1849), the most important folk artist of American art, was born and lived all his life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. About a hundred of his paintings survive, 62 of which are versions of "The Peaceable Kingdom". Recently, his Peaceable Kingdoms have been selling for more than $4 million apiece, and the other works at more than a million. As is so often the case, he was born in poverty and spent his life in poverty, so the financial benefits have all gone to middle-men.

Hicks had to overcome an additional handicap. Quakers disapproved of painting things up just for show, and they strongly disapproved of the vanity underlying the act of having a portrait painted of yourself. In fact, the early Quakers would not even permit their names to be placed on their tombstones.

Hicks was apprenticed into the wagon business and showed a talent for painting them. From that, entirely self-taught, he migrated into the business of painting business signs in an age of limited literacy. The Blue Anchor Tavern, the King of Prussia Inn, the Crossed Keys Tavern and the signs of various tradesmen were an essential part of conducting business. It is easy to see these tradesmen signs in the easel paintings of Hicks' later career, which reduce themselves to rearrangements of such individual sign paintings to make a coherent canvas.

If you have seen one "Peaceable Kingdom" you haven't seen them all, but you only need to see one to be able to recognize the others at sight. They generally form a group of wild animals and an occasional child in the right foreground, with a grouping of Quakers and Indians in the left background, taken from Benjamin West's famous portrayal of Penn signing the treaty of peace with the Delaware Indians. The scene is taken from Chapter 11 of Isaiah, in which the lion lies down with the lamb.

Hicks was not a successful farmer, and he had to overcome Quaker resistance even to sell religious paintings with a Quaker moral. No doubt the resistance was strengthened by the fact that his cousin Elias Hicks had split the Quaker church into two (Conservatives and Hicksites) in 1827, and Edward was himself a strong itinerant preacher. Although the plain message of the Peaceable Kingdom is reconciliation between the two branches of Quakerism, he probably encountered a fair amount of coolness among the Conservative opposition.

Hicks was neither an educated nor a sophisticated man. It is forgivable that he made such a strong Old Testament statement when he and his cousin represented a dissenting sect that was gravely doubtful about the wisdom of allowing your life to be ruled by biblical verses.

The Quaker Who Would Be King

|

| Inazo Nitobe |

The story of Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933) comes in two forms, one from the Philadelphia Quaker community, and the other from his home, in Japan. One day in Philadelphia, a well-known ninety-year-old Quaker gentleman, rumpled black suit, very soft voice -- and all -- happened to remark that his Aunt had married a Samurai. A real one? Topknot, kimono, long curved sword, and all? Yup. Uh-huh.

That would have been Inazo Nitobe, who met and married Moriko, nee Elizabeth Elkinton, while in college in Philadelphia. He became a Quaker, and when the couple returned to Japan, the Emperor then found himself confronted with a warrior nobleman who was a pacifist. You can next perceive the hand of his Quaker wife in the deferential diplomatic suggestion that there were vacancies for Japan at the League of Nations and the Peace Palace in the Hague. Perhaps, well perhaps, there could be service to his Emperor as well as his new religion in such an appointment for her new husband. Good thinking, let it be done. As far as Philadelphia is concerned, Ambassador Nitobe next appeared when Japan was invading Manchuria. The Emperor had sent Nitobe on a tour of America to explain things. At the meetinghouse then on Twelfth Street, Nitobe adopted the line that Japan was only bringing peace and order to a chaotic barbarian situation, actually saving many lives and restoring quiet. After a minute of silence, Rufus Jones rose from his seat on the "facing bench": He was having none of it. And that was that for Nitobe in Philadelphia.

The other side of this story quickly appears if you go to Japan and ask some acquaintances if they happen to have heard the name Inazo Nitobe. That turns out to be equivalent to asking some random American if he has ever heard of Abraham Lincoln. To begin with, Nitobe's picture appears on the 5000 Yen ($50) bills in everybody's pocket. He was the founder of the University of Tokyo, admission to which now is an automatic ticket to Japanese success. He wrote a number of books that are now required reading for any educated Japanese. A number of museums, hospitals, and gardens are named after him; one of them outside Vancouver, at the University of British Columbia.

Nitobe's father, Jujiro Nitobe, had been the best friend of the last Shogun, deposed by the return of the Emperor to effective control after Perry opened up Japan to Western ideas. The Shogun was beheaded, of course, and the tradition was that the victim could ask his best friend to do the job because he would do it swiftly. Jujiro was unable to bring himself to the task, refused, and his family was accordingly reduced to poverty. Subsequently, the Samurai were disbanded by the newly empowered Emperor, given a pension, and told to look for peaceful work. Inazo Nitobe was in law school when the Emperor's emissary came and said that Japan did not need culture, it had plenty of culture. The law students would please go to engineering school, where they could help Japan westernize.

Nitobe later wrote a perfectly charming memoir, called Reminiscences of Childhood in the Early days of Modern Japan , which dramatizes in just a few pages just how wide the cultural gap was. For example, Nitobe's father brought home a spoon one day, and this curious memento of how Westerners eat was placed in a position of high honor. One day, a neighbor ordered a suit of western clothes, and hobbled around it, saying he did not understand how Westerners are able to walk in such clothes. He had the pants on backward.

One of Nitobe's greatest achievements was to struggle with his appointment as Governor of Formosa (Taiwan). Japan acquired this primitive island in 1895, and Nitobe got the uncomfortable role of colonist in Japan's first experience with colonization. He sincerely believed it was possible for Japan to bring the benefits of Westernization to another Asian backwater, but just as the British found in their colonies, there was precious little gratitude for it. Although he was undoubtedly acting dutifully on the Emperor's orders when he later came to Twelfth Street Meeting, he surely knew -- perhaps even better than Rufus Jones -- that there was something to be said on both sides, no matter how conflicted you had to be if you were in a position of responsibility. This most revered man in his whole nation almost surely saw he had been a complete failure in Philadelphia.

Zane Grey, Dentist

|

| Zane Grey |

The American myth of the cowboy has much more Philadelphia flavor than one would suppose, considering the far-western location of the cows, the New York origins of Teddy Roosevelt, and the implication of southern aristocracy running through the dispossessed gentlemen riding the purple sage. The myth of the noble cowboy is behind much of what elected Ronald Reagan, the Californian.

Nevertheless, the Homer who started this epic Iliad was Owen Wister of Seventh and Spruce, Philadelphia.His book The Virginian might be summarized in a single quotation, "When you say that to me, smile." Behind that, of course, was Wister the lion of the Philadelphia Club rebuking his peers. The real theme was "I searched the drawing rooms of Philadelphia and Boston for the gentleman. And I found him on the frontier."

|

| James Fenimore Cooper |

Part of this complex theme is the underlying outdoors fraternity linking cowboys and Indians, tracing back to James Fenimore Cooper of Camden, NJ ennobling the noble savage in the Last of the Mohicans. Fair treatment for the natives has long been a strong Quaker theme, tracing back to William Penn's deep wisdom about colonization, and also personified in Corn planter the thoughtful Chief of the Iroquois, or Joseph Brant the scholarly Indian leader who translated the Bible, charmed the English monarchy, and then returned home to massacre the town of Lackawaxen. There's a theme here of shooting the circling Indians off their ponies, take no prisoners, mixed with the tragic white woman who falls in love with the equally tragic Indian brave, all doomed from the start. There's the sheriff with a shady past, going forth to shoot it out with outlaws while his Quaker wife watches out the window, because he is true to the Code of the West. Grace Kelly was surely no Quaker, but the Philadelphia hint is unmistakable.

It may take a century or more, but some American Homer is surely going to write the definitive epic based on this story. Meanwhile, Zane Grey tried his best. His version has a lot of Philadelphia in it, and not only because he went to the University of Pennsylvania on a baseball scholarship. He graduated from Penn as a dentist, practiced in New York for six years, and hated every minute of it. Writing cowboy stories in his spare time, he gladly quit dentistry after his first publishing success, and moved over to Lackawaxen, PA to write in the woods. Lackawaxen is a great fishing spot, and was once a flourishing resort community at the confluence of the railroad and canal systems, now long since decayed and gone. He lived there for fifteen years, and asked to be buried there. His home is now a museum.

Pearl Grey became Zane Grey by way of P. Zane Grey, DDS. He had been born in Zanesville, Ohio, the son of a Quaker mother who belonged to the founding Zane family, and a preacher-farmer father who had insisted on the dentistry idea. All his life, Zane Grey was a vigorous sportsman, most unlikely to warm to an effeminate name like Pearl. Or gentle Quaker ways, either; but like his cowboy heroes he was obedient to his code. Most of his life he managed to go fishing more than two hundred times a year, and produced two thousand words of writing almost every week. He wrote a hundred thousand words a year, and kept it up for thirty years. He published sixty books in his lifetime, and thirty more of his books have appeared since his death. His material was the basis for forty movies, and many short stories. Six of his books are about fishing, but mostly he wrote sophisticated variations on the theme of the wild West, the cowboy true to his code, and the noble savage. He was the first American author to become a millionaire from his writings. It seems sort of a pity that he was overtaken by the pressures of commercial success, and consumed by his extraordinary drive and diligence to the point where very little time was left for the Great American Epic of the West. He lived in California for many years, but it seems unlikely there were enough hours in his day to shake loose from Quaker origins.

The same is true of Ronald Reagan and his Iowa origins, but somehow that does not capsulize what the American cowboy represents. Somehow there is something in common about the former Confederate cavalrymen who were the early cowboys, the Quakers befriending the Indians, and the Iowa boy who was to negotiate the end of the Cold War with the Evil Empire. It is somehow a matter of remaining true to your roots while dealing fairly with strangers. It lies in Reagan's motto as much as the Virginian's barroom warning. Trust, but verify.

Two Pacifists: Einstein and Eddington

|

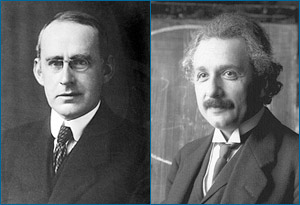

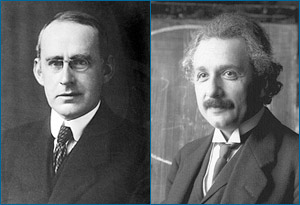

| Einstein and Eddington |

Very few claimed to understand what Einstein's Theory of Relativity was all about, but everyone could understand that giving a wartime Nobel Prize to a conscientious objector on the enemy side was political dynamite. It was not entirely a clear case; Einstein had indeed been a C.O. and was indeed the only member of the 94-person Prussian Academy to refuse to endorse the War. However, he had such a long history of taking the unpopular side of every argument that it was not certain whether he opposed the war or was merely sticking his thumb in the Kaiser's eye. At the same time, the most promising English astrophysicist, Arthur Eddington, was petitioning as a Quaker to be granted alternative service rather than be compelled to fight. Since Eddington was just about the only person claiming to understand and endorse Einstein's incomprehensible idea, it did not seem convenient to the British government to seem to endorse a German claim to enormous scientific achievement. It was decided to agree to Eddington's draft exemption on condition he conducts his own proposal for a definitive test of the theory. According to this idea, the light coming from a distant star should bend as it went past the sun. This proposal had the hidden advantage that a test could not take place until the 1919 eclipse of the sun, visible only from Africa or Brazil.

The experiment was hailed as a success, and a Nobel Prize followed shortly afterward, even though there were storm clouds over Brazil, and technical difficulties in Africa resulted in a rather blurred obscurity which would have baffled the public except for the enthusiastic acclaim of the only distinguished English scientist likely to understand the experiment. As telescopes have improved over the intervening century, it is now possible to observe the gravitational pull of much larger celestial bodies than the sun on a light which is coming to the earth from much more distant stars. Therefore, even schoolchildren can today see photographs of pinpoint starlight twisting into arcs of light while passing distant galaxies. Einstein the German has triumphed over Isaac Newton the Englishman, although the heady triumph probably did somewhat go to the heads of both Einstein and Eddington. Eddington the birthright Quaker allowed himself to be knighted, Einstein endorsed the dubious pacifist uprisings in Palestine, Eddington made a career of explaining puzzling scientific theories to the appreciative public. The direction of all this became clearer as some of the new theories Eddington promoted were discredited, and Einstein's pacifism has certainly become clouded by later thermonuclear events which he had a large hand in promoting.

Of the two, Einstein has proved to be the greater scientist, but Eddington would have been a scientific luminary without any association with the German, perhaps even a greater one without inevitable comparison between the two. Einstein spent the last 23 years of his life on the fringes of Philadelphia, at Princeton, but Philadelphia had little consciousness of his presence.

Rufus Jones, Quaker

|

| Rufus Jones |

Rufus Jones (1863-1948) dominated the Quaker religion for two generations, causing a transformation which deserves to rank with that of George Fox, William Penn and Elias Hicks. A few elderly Quakers still remember him in person, mostly as an old gentleman who tended to lean back while he spoke, usually hooking his thumbs in the sides of his vest. He was a prodigious writer, having once made a promise to himself that he would read a new book every week, and write a new book, every year. He kept that up for thirty years.

|

| Haverford College |

As a matter of fact, that understates his output. His published works were collected by Clarence Tobias at Haverford College, and run to 168 volumes, plus 8 boxes of pamphlets and articles. His family also donated his personal papers to the College, and they require 75 linear feet of shelf space.

His stated occupation would have been Professor at Haverford College, where his personal influence on the undergraduates was as profound as their influence was to be on the rest of the world. He is regarded as one of the founders of the American Friends Service Committee and the single greatest influence in reuniting the two divisions of Quakerism, although some of the formalities were not completed until after his death.

One other index of his remarkable energy was that he crossed the oceans more than two hundred times during his lifetime.

Perhaps the arrival of mass communication has made it possible to have equal impact with less effort. But Rufus Jones stands for the principle in life, that it never hurts to work just a little harder. If high school students are thinking of applying for admission to Haverford, they better understand what is going to be expected of them.

Henry Cadbury Dresses Up for the King

|

| Henry Cadbury |

There are a few old Quaker Clothes in the attics of their descendants, and on suitable occasions, an old broad-brimmed hat or two will appear at a Quaker gathering, for amusement. Quakers gave up the old style of "plain dress" when it became generally agreed that such eccentric dress was not plain at all but rather drew attention to itself. On the other hand, there is a distinctly unfashionable quality to almost everything Quakers do wear. When silk and nylon stockings were fashionable for women, Quaker women often wore black stockings. When it became the style for women to sport black stockings, Quaker women usually wore flesh-colored nylons. Among men, thin metal-trimmed spectacles displayed the same counter-fashionable tendency. Nowadays, these little quirks are often public signals among strangers, a way of wig-wagging "I notice you are a Quaker, so am I." And of course, unfashionable clothes are cheaper, and that's always a good thing.

And so it happened in 1947 that the Quakers were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, with information passed along that white tie and tails were the expected form of dress at the ceremony. Henry Cadbury was selected to receive the award on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, and you can be sure Henry Cadbury didn't own a set of tails. Henry was also very certain he wasn't going to go out and buy a set, just for a single wearing.

The AFSC collects used clothing, to distribute to the poor. Henry inquired whether there might be a set of white tie and tails to be found in the used-clothing bin, and luckily there was. It had been collected on behalf of the Budapest Symphony Orchestra when that impoverished but distinguished group of musicians was invited to give a concert in London. One of the monkey suits more, or less, fit Henry.

So, after investing in dry cleaning and pressing, Henry packed it up and went off to Oslo, to meet the King.

James A. Michener (1907-1997)

|

| James A. Michener |

James Michener seemed headed for a recognizably Quaker life until show business rearranged his moorings. He was raised as a foundling by Mabel Michener of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, under circumstances that were very plain and poor. Many of his biographers have referred to his boyhood poverty as a defining influence, but they seem to have very little familiarity with Quakers. When the time came, this obviously very bright lad was offered a full scholarship to Swarthmore College, graduated summa cum laude, went on to teach at the George School and Hill Schools after fellowships at the British Museum. And then World War II came along, where he was almost but not exactly a conscientious objector; he enlisted in the Navy with the understanding he would not fight.

While in the Pacific, he had unusual opportunities to see the War from different angles, and wrote little short stories about it. Putting them together, he came back after the War with Tales of the South Pacific. Much of the emphasis was on racial relationships, the Naval Nurse who married a French planter, the upper-class Lieutenant (shades of the Hill School) who had a hopeless affair with a local native girl that was engineered by her ambitious mother, as central characters. Michener himself married a Japanese American, Mari Yoriko Sabusawa, whose family had been interned during the War. There are distinctly Quaker themes running through this story.

And then his book won a Pulitzer Prize, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein made it into a Broadway musical hit, then a movie emerged. The simple Quaker life was then struck by the Tsunami of Broadway, Hollywood, show biz and enormous unexpected wealth. Just to imagine this simple Bucks County schoolteacher in the same room with Josh Logan the play doctor is to see the immovable object being tested by the irresistible force. Michener retreated into an impregnable fortress of work. He produced forty books, traveled incessantly, ran for Congress unsuccessfully, and was a member of many national commissions on a remarkably diverse range of topics. Although he lived his life in a simple Doylestown tract house, he gave away more than $100 million to various charities and educational institutions.

In his 91st year, he was on chronic renal dialysis. He finally told the doctors to turn it off.

Victor Rambo, Indian Eye Surgeon

|

| Apostle of Sight |

There have been at least twelve documented generations of the Rambo family in Philadelphia. Historical justification can be found for the idea that this was the first family to settle within what are now the city limits. Victor Clough Rambo MD was an unpaid intern at the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1927; you will find his nameplate on the wall.

Victor early made up his mind that he was going to go where he could do the most good. Considerable thought led him to learn how to extract cataracts, and go to India to extract as many as he could. from time to time, he would return to America to visit family, and to give some speeches to raise money for his project.

The builders of our enormously costly hospital castles might give some thought to the fact that Victor did most of his surgery in tents. His system was to send out teams to the next two villages, whenever he was, with the news, "Bring in your blind people, the eye doctor is coming." When he then arrived, he set about operating on cataracts from dawn to dusk, in a country where the supply of cataracts was essentially unlimited. There was no time to operate on the comparatively minor visual disturbances so commonly treated in America today; he had to concentrate on people who were really blind, and in both eyes.

He wrote a book about his experiences, and perhaps there you could find data to calculate the number of people who were restored to a useful existence by his efforts. Surely, it was thousands. He just kept going at it, and when he died he was a very old man.

Contemporary Germantown

The Strittmatter Award is the most prestigious honor given by the Philadelphia County Medical Society and is named after a famous and revered physician who was President of the society in the 1920s. There is usually a dinner given before the award ceremony, where all of the prior recipients of the award show up to welcome to this year's new honoree.

|

| Bockus |

This is the reason that Henry Bockus and Jonathan Rhoads were sitting at the same table, some time around 1975. Bockus had written a famous multi-volume textbook of gastroenterology which had an unusually long run because it was published before World War II and had no competition during the War or for several years afterward; to a generation of physicians, his name was almost synonymous with gastroenterology. In addition, he was a gifted speaker, quite capable of keeping an audience on the edge of their chairs, even though after the speech it might be difficult to recall just what he had said. On this particular evening, the silver-haired oracle might have been just a wee bit tipsy.

Jonathan Rhoads had likewise written a textbook, about Surgery, and had similarly been president of dozens of national and international surgical societies. He devised a technique of feeding patients intravenously which has been the standard for many decades, and in his spare time had been a member of the Philadelphia School Board, a dominant trustee of Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, and the provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Not the medical school, the whole university, and is said to have been one of the best provosts of the University of Pennsylvania ever had. When he was President of the American Philosophical Society, he engineered its endowment from three million to ten times that amount. For all these accomplishments, he was a man of few words, unusual courtesy -- and a huge appetite in keeping with his rather huge farmboy physical stature. On the evening in question, he was busy shoveling food.

"Hey, Rhoads, wherrseriland?". Jonathan's eyes rose to the questioner, but he kept his head bowed over his plate.

"HeyRhoads, Westland?" The surgeon put down his fork and asked, "What are you talking about?"

"Well," said Bockus, "Every famous surgeon I know, has a house on an island, somewhere. Where's your island?

"Germantown," replied Rhoads, and returned attention to his dinner.

Lin

Lindley B. Reagan, M.D.

July 16, 1918 -- September 10, 1995

|

| Lindley B. Reagan, M.D |

The first and oldest hospital in America, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce Streets, always had a strong Quaker flavor but a unique medical tradition as well. Since it was the only American hospital for decades, later becoming the home hospital of the first medical school in the country, it impressed its ideals and traditions on the whole of American medicine. However, it imposed so many difficult demands on its trainees that a century or more of an evolving profession simply moved away from copying it. It was, in 1960, the last hospital in the country to begin paying its resident physicians anything at all, one of the last privately controlled American hospital to adopt a billing and accounting department, and one of the last if not the last to regard a handful of private beds as merely a convenience for the patients of the staff physicians. In 1970 its method of maintaining inventory was to notice that the supplies on the shelf were running low, and ordering some more. It was founded in Benjamin Franklin's words, for the "sick poor, and if there is room, for those who can pay," and could only survive into the late 20th Century through private donations and the freely contributed services of the doctors, student nurses and administration. No amount of money could induce people to work as hard as they worked. You might say this was the only aspect of Medieval monasteries which Philadelphia Quakers thought worthy of imitating.

Somewhere in this set of ideas was the treasured concept of a rotating internship, preferably two years long, prior to entering specialty training through a residency. In 19th Century Vienna, it was a matter of rule that an intern was just that, physically confined within the walls for the term of service, and a resident was just that, someone who lived on the campus. The Pennsylvania Hospital had no such rule, but since it paid the doctors nothing for five or six years of eighty-hour weeks, their poverty forced them to satisfy the Viennese rules by default. Entertainment was bridge or poker in the intern quarters, conversational chit-chat was a description of bizarre cases or peculiar patients, a weekend "off-call" was a good time to catch up on correspondence. There were student nurses around, of course, but the matron was a pretty no-nonsense chaperon. Every class of interns contained one or two millionaires by inheritance, but peer pressure made them nearly indistinguishable in the daily routines. Aristocrats' main value to the resident physician community was their access to the ruling families in the city, and hence to the governance of the hospital, in case governance should occasionally abuse the vulnerability of the trainees.

I find in retirement that most of my colleagues are now willing to tell stories of the "old days" which they were unwilling to tell at the time. Over several glasses of the finest single-malt in a walnut-paneled club, one such story recently surfaced. It concerned Lin.

Lin was a member of an old Quaker family, surprising everybody during the Second World War by volunteering as a junior physician in the Navy. He was assigned to a marine regiment in the Pacific Theater and went through some of the most murderous fightings on Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. Our grapevine reported that the enlisted Marines in his outfit absolutely worshipped him, and I easily believe there was a lot of quiet heroism behind that gossip. He told me he had decided to become an internist while in the Pacific, but somehow only a surgical residency was available when the War was over, so he took it. He was probably the best internist on the staff, and it showed in his conduct of surgery, where it sometimes matters more what you decide to cut than what you cut. He always looked exhausted, but never hesitated to drive himself another hour when the situation demanded it. One day, he had to excuse himself from an operation, an almost unheard-of event, and testing his own urine, found it loaded with sugar. So, the soft-spoken Quaker internist who was primarily doing surgery had to add the burden of insulin injections to his load. If he ever complained about that or any other thing, no one could remember hearing it.

At about the third glass of single malt, the story came out. My old friend, like the rest of us, had to spend a year as a surgical intern during the two-year rotating internship; he hated surgery and didn't mind telling the world. At the moment in question, he was the assistant at some neck surgery, with Lin performing the actual surgery. He was told to take a long pair of scissors and cut off the excess strands of sutures after Lin tied the knots; that was known as trimming the ligatures. They were working deep in the crevices of the patient's neck. Lin held up the loose ends of the knot and ordered, "Cut". My friend inserted the long scissors into the hole and snipped -- accidentally cutting right through the jugular vein.

As would be expected, a fountain of blood came up out of the hole, and Lin stopped it by putting his thumb on the cut ends of the vein. "Well," said Lin, "I guess we'll have to fix that." And did.

With tears in his eyes, my octogenarian friend cried out to the startled clubroom. "God bless you. God bless you, Lin."

Perhaps the point isn't clear to those who didn't go through the process, so let's be more explicit. Both my friend and I worshipped Lin, as a person, a teacher, and a surgeon. He was the perfect agent for his patients, without the tiniest trace of conflict of interest, income-maximizing or whatnot. He was as technically skillful as it is useful to be, but he was the thinking man's surgeon as well as the utterly faithful servant of the best interests of the humblest patient. He was, in the opinion of his closest professional associates, the best surgeon in the world. In need of surgery ourselves, all of us would have flown the Atlantic to have him operate on us. For reasons of his own, he was to spend the forty years of his professional life in a small country town with a small hospital, scarcely a famous surgeon but a beloved one to his community. Over the past sixty years, I have had a number of opportunities to know many surgeons who would be in contention for the title of the best surgeon in the world. Some have written books, some have struggled successfully upward through vicious competition, some of them would be called "Rainmakers" if the research world followed the pattern of lawyers and architects. One or two have won Nobel Prizes for surgical innovations, but that's different from being the best surgeon around. The best surgeon in the world was Lin, faithfully plying his trade in a little town that could not possibly know how lucky they were.

Philadelphia Chromosome

Every Spring for the last 185 years, the Franklin Institute has honored the most distinguished scientists alive; Franklin would certainly be proud of the Institute named after him. In recent years, many awards were combined into two categories, the Bower Awards and the Benjamin Franklin gold medals. Unlike the Nobel Prize, the Franklin Institute Medals are not given for eminence in a designated field of science, but rather are given out by a hard-working committee of scientists who ask themselves What are the really hottest scientific fields at present, and then ask panels of international referees Who is most eminent in that field? The awards thus effectively avoid fields that are temporarily stale and static, by being unrestricted in advance to particular fields. The approach of searching for the greatest minds rather than greatest achievement may well lead to the same award, but the method of choice seems more harmonious with the spirit of Benjamin Franklin, who not only excelled in the field of electricity but actually invented that whole field. The subtle shift in emphasis seems to have been well received; this year's Awards Banquet was over-subscribed before the invitations were printed, and a capacity audience of 800 attended a superb reception, dinner and audio-visualized live ceremony. Actually, the ceremony extends for a whole week, with scientific symposia and in-person meetings with high school students designed to interest them in science.

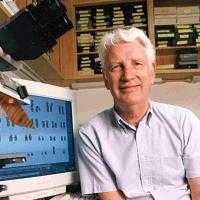

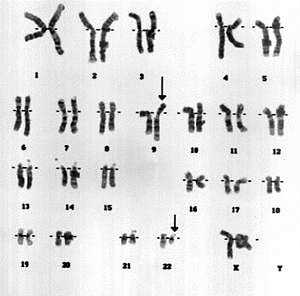

This year eleven scientists, the most prominent of whom were Bill Gates and Peter Nowell, received the medals. We'll get to Bill Gates in a while; for the present, let's concentrate on Peter Nowell, who invented the Philadelphia Chromosome. What's that?

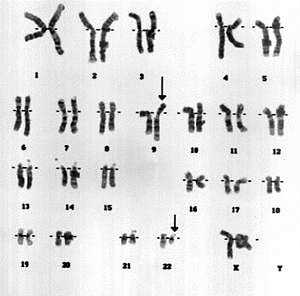

|

| The Philadelphia Chromosome |

Well, from 1921 to 1955, it was generally held that people, members of the human race, contained 48 chromosomes in every cell in their bodies. The chromosomes were thought to contain the genetic code governing our biological construction, explaining the difference between us and fruit flies, which for example only have four chromosomes per cell. After painstakingly examining the appearance of the chromosomes in different people and in cancer cells, it was then generally held that cancers never seemed to have any genetic abnormality. After all, the chromosomes of cancer cells looked exactly like those in normal tissue: Forty-eight chromosomes, never differing in cancers, so go look somewhere else for the cause of cancer. Unfortunately, the state of scientific development fifty years ago can be summarized by noting that about that time it then became established we really only had 46 chromosomes, not 48. As for cancer, the M.D. pathologist Peter Nowell, then noticed in 1956 that a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia had an extra translocation on one particular chromosome, giving it a funny shape. This translocation was furthermore present in every single other leukemic cell suggesting that one cell had somehow undergone a single mutant change, and all the rest were its descendants. At least in CML (chronic myelogenous leukemia), it suddenly looked as though the cause had been found since the further study revealed the same was true of just about everyone who had CML. At first, it was felt that while maybe the cause of this particular type of cancer had been found, every other cancer might still be caused by something else. Not so. From believing no cancers were genetic in origin, Peter Nowell started us on the path of now being confident all cancers have a genetic cause.

|

| Dr. Peter Nowell |

How could we all have been so wrong; can't scientists even count up to 46? No, as a matter of fact, in 1955 it was pretty hard. If we couldn't even tell how many of them were there, it's obvious the comment they all looked alike wasn't worth very much. As Peter shyly admits, his discovery was a result of being trained as a physician rather than as a life scientist; he knew what leukemia looked like, but at that time he didn't know very much about chromosomes. It happens chromosomes spend most of their lives expanded into tiny filaments too small to examine under the microscope. But as they enter the stage of cell division called metaphase, those filaments shorten and thicken up, becoming a lot easier to examine. As a pathologist, Peter didn't bother to stain his slides in dilute salt solution, but just washed them in tap water. The tap water had caused the cells to swell up and burst; those that happened to be in metaphase dumped their stubby chromosomes out where they could be stained and looked at. Simple. Doesn't everyone wash slides in tap water?

So fifty years ago, the general question of what causes cancer finally narrowed down to the right sort of specific question. Thousands of scientists, spending billions of dollars from the National Institutes of Health, sharpened the focus of their search considerably. It certainly looks as though someone is going to carry the search the final step, pretty soon. However, the fact that fifty years of intensive study still hasn't quite found the answer is an illustration of how fiendishly difficult the search really is. Each year that might have been spent futilely avoiding genetic searches would have added one year more before the answer was finally found. By the way, why is it called the Philadelphia Chromosome? In 1955 it had been decided by the scientific community that every genetic abnormality would be named after the city in which it was discovered. Dr. Peter C. Nowell of the University of Pennsylvania and the late Dr. David Hungerford of the Fox Chase Cancer Center were the joint discoverers, so obviously it was entirely a Philadelphia discovery; at that time it had been made a custom that genetic abnormalities were named after the city where they had been first found.

It would be a mistake to conclude that nothing new has been discovered in half a century of research. It has been established that not only Myelocytic Leukemia but essentially every cancer starts with some genetic abnormality, which triggers the expression of "mini RNA". These abnormalities then apparently express a cancer-producing action by triggering an abnormal factor in the cell signaling system, called tyrosine kinase. Drugs with the effect of paralyzing that enzyme have been found to be curative in 95% of cases of chronic myelogenous leukemia, and some other forms of lymphoma. We're certainly getting closer, step by unexpected step, to the answer. In fact, we may be getting even closer to a point where drug research can jump to seeking cures without precisely defining how the cancer was caused. After all, if cancer is caused by a chain of cellular events, it may not matter where you break the chain. That realization appeared with, first aspirin and then the statin drugs, for treating heart attacks and strokes, even though we are still not completely clear about how atherosclerosis is produced. Meanwhile, the death rate from hardened arteries has dropped by half.

It wouldn't be right to omit mention of Peter Nowell's Quaker heritage. Although he isn't a Quaker, his mother was a Matlack, a direct descendant of Timothy Matlack, the Haddonfield Quaker who was the scribe for the first writing of the Declaration of Independence. Sitting in silent Quaker meeting, polishing and simplifying one's message before delivering it, is very good training for a habit of simple, direct thought. As Dr. Nowell phrases it, he is a chronic "lumper" of ideas, when so many scientists are content to be "splitters". Splitting complexity into its essential components is a useful approach. But somewhere, someone has to get to the heart of the matter.

Doing Well, Doing Good.

|

| Lynmar Brock |

Lynmar Brock is a Quaker, so what he does is surprising. He lives on a farm, but is Chairman of the Board of a food distribution corporation. He's also chairman of several other boards. He's written several books, and among them, a novel Must Thee Fight? relates the tribulation of one of his pacifist ancestors who nevertheless became a soldier at the Battle of Brandywine. The theme of this emotional conflict parallels the author's own struggle over being a conscientious objector who ultimately volunteered for the Navy because he felt he could not stand by while others fought his battles for him. The face of the soldier with a musket on the book jacket is his own.

|

| Rotary Seal |

When American forces recently entered Afghanistan, a great many people were forced to become refugees. Lynmar Brock was on the board of Rotary International, where a decision was made to provide relief for the refugees, and Mr. Brock flew over to lead the effort on the ground. Rotary raised $2 million almost immediately, and the task was to translate the money into something the refugees really needed. Since "shrinkage" is a common fate for refugee shipments, Rotary bought locally. They were able to distribute 83,000 pairs of shoes, 53,000 blankets and similar quantities of a number of other basic needs. Ultimately, the three-year effort raised $115 million and distributed items in the millions. It was important to give the goods to the local tribal chief, who then redistributed to the members of the tribe. To give it directly would undermine the authority of the chief, very likely provoking him to interfere with it. Accordingly, it is essential for relief workers to make friends with the chieftains, and it is essential to avoid the appearance of being a sap. All of the clothing was stamped with a big indelible yellow Rotary Seal; if it turned up in the black market, it would still be obvious what its source had been. At the same time, it was essential for donors not to appear to be soldiers. One of the missions of the group was to show the Afghans that Americans were real people who cared, and not all were soldiers. That they were successful in this way was brought out by one tribal chief coming forward and saying, "Teach us English. It's the language of the world."

Some influential Rotarians are active in American ophthalmological circles, and arranged to have American eye surgeons extract a great many cataracts from Afghans otherwise destined to a life of blindness. Since the Taliban routinely poisoned the wells, it was vital that farmers like Lynmar Brock were able to show how to repair or replace the local water supply. It might have been better to replace opium farming with tomatoes, but a compromise was made to replace opium with marijuana. That's an improvement, of sorts. The danger inherent in this work must not be shrugged off. All vehicles of foreigners were preceded and followed by at least six local soldiers. As the cavalcade moved from one tribal area to another, the soldiers were changed for soldiers of the new tribal area; their loyalty just had to be trusted. And, indeed, the co-chairman of the committee was mysteriously murdered one day.

The Rotarians return home full of praise for the U.N. field workers, mostly European, who are actually engaged in foreign relief work. The headquarters staff back home at the U.N. are described with only a shrug that speaks volumes, but it is useful for us all to keep the distinctions in mind.

Lynmar says it's great to be home. In his busy life there's work to be done on the farm, and in his corporation, and writing another novel. And there is supervision also needed for the Rotary efforts in the Ivory Coast. It's not completely certain, but sometimes he actually gets some sleep.

Nixon, Reconsidered

|

| Richard M Nixon Says Goodbye |

Many Quakers held private their opinion of Richard M.Nixon. For forthright Quakers there seemed a little too much Uriah Heap about him, too much politician let's say. As his Presidency unfolded, he took many policy positions that distressed a conservative sense of appropriateness; many conservatives reserved judgment about the steadiness of this Californian. He introduced wage and price controls, announced he was an economic Keynesian as he assumed everyone else was too, allowed inflation to get out of control, severed connections between the dollar and gold. Those are not crimes, but to conservatives, they were a betrayal. Quite different actions provoked liberals to charges of villainy, but natural defenders hesitated to defend him even when they felt he was probably more sinned against than sinning. For example, Nixon was attacked for pursuing the evidence against Alger Hiss. In view of the gravity of the offense, it was a responsible position to investigate the evidence about Alger Hiss, and quite unreasonable to defend Hiss if he turned out to be guilty. It was not Nixon the accuser who was on trial in this case, but you might have thought so.

|

| Henry Kissinger |

So before we close the history books on Nixon, let's remember that press reports proclaimed he ran for President in 1968 on the claim that he had a secret plan to bring the Vietnam War to an end. He apparently never claimed such a thing but found himself boxed in by reluctance to assert in an election campaign he had no idea how to end the war. After a few years no plan emerged, the war continued, Nixon was branded a liar. Tricky Dick had stolen an election with fraudulent flim-flam. He was hounded out of the office with the prospect of a successful impeachment ahead of him. Impeachments are political events, not judicial ones. Impeaching a president for covering up Watergate without accusing him of causing it, merely preserves appearances for the vote to go either way. He was the only American president to resign.

Forty years later, it begins to emerge that after the election he and Henry Kissinger finally figured out that China was behind the Vietnam War, may have started it, but in any event was the only power that could bring it to an end. Subtle and protracted secret negotiations purporting to concern ping-pong matches were undertaken in 1971, eventually, Nixon made his famous 1972 secret trip into the heart of Communist China. Just what explicit promises were secretly exchanged is still not clear, may never be. But it can be clearly observed that in April 1972 America did begin a steady series of troop reductions in Vietnam, and soon began steady matching progress toward helping primitive China ultimately become a marvel of peaceful economic development. In retrospect, that would have been a pretty fair offer for peace. No useful duplicity could have been successful if either side had been explicit in public about secret understandings. Both countries and the whole world are nevertheless safer for the shrewd insights that envisioned the process, the subtlety of the discussions, and the political risks accepted. It is difficult to think of any comparable public service since James Madison conceived and achieved the U.S. constitution in deliberate secrecy. Madison was to endure years of well-deserved attack for his manipulations as a politician, just as Nixon did, without once alluding to their greatest national service for vindication. It's true, of course, that Madison kept careful secret diaries, and Nixon kept tape recordings. It seemed to be sufficient to know that someday, somehow, the public would find out.

Herbert Hoover, Mining Engineer

The tragedy of Herbert Hoover

|

| Herbert Hoover |

|

| Hilter & Mussolini |

After leaving his meteoric twenty-year business career in boredom at its lack of challenge, he took on a monumentally successful job of administering famine relief to a European continent devastated by World War I. On occasions in the course of it, he personally confronted both Hitler and Mussolini with disdain. Franklin Roosevelt was so impressed that he suggested him as a Democratic candidate for the Presidency; Hoover declined. He was nominated at the Republican convention on the first ballot, elected in a landslide. As President, he hit the ground running, simply peppering the Congress with innovative programs and proposals. A substantial part of what would be known as Roosevelt's New Deal grew out of initiatives that Hoover had begun during his short presidency.

|

| Stock Market Invincible |

Under the circumstances, it is not surprising that Hoover was disturbed by the irrational exuberance of the stock market in 1927-28, undisposed to resist proposals by George Harrison of the Federal Reserve to deflate the stock bubble by tightening the money supply. Some observers feel the fatal illness of Benjamin Strong (President of the New York Branch) weakened the resistance of the Federal Reserve to this adventurism. The stance of Hoover is not now known, but it must have been a toss-up between lifetime allegiances to hard-money and resistance to government intrusion into commerce, particularly by a comparatively new agency. In any event, tightening money worked too well. The stock market tanked in October 1929 FB is shutting down in March,

|

| Stock Market Crash |

followed quite promptly by the whole economy. The irony is that Roosevelt proceeded to run for twenty years with the claim that the Depression was caused by Hoover's failure to restrain the 1928 stock bubbles. In fact, the befuddled Federal Reserve bounced around during Roosevelt's time in office as well, turning a recession into the deepest depression in history. When England went off the gold standard, the Federal Reserve tightened again to prevent a flight of American gold to speculators. The result was a run on the banks, so the Fed loosened again, and half of the American banking system disappeared. Following the 1929 crash, the stock market continued to go down -- for fourteen years.

|

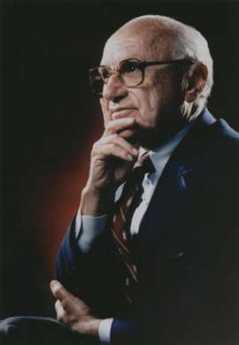

| Milton Friedman |

After a while, it became clear to everyone that three things -- the money supply, the economy, and the stock market -- go up and down together. The basic question was the same as the political one -- which one goes first, and which ones follow? Although the political parties continue to spin the facts, the world of economists seems nearly unanimous that Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz and Milton Friedman settled the matter some time ago. Their classic work of scholarship,A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1963 , traces out four American and eleven foreign examples of shifts in monetary tightness which were unrelated to the economy, and demonstrate that the economy promptly follows the direction of the money supply. Almost all of these anomalies took place during the interval after World War I, when the gold standard was temporarily suspended. Different countries returned to gold at different times, and after the 1929 crash abandoned it in different ways at different times. Since the publication of Friedman's work, independent scholars have provided over forty confirmations of the sequence, money leads, the economy follows. And politicians posture. There is a disconcerting note, however. Almost all of the examples studied by monetary scholars could be used as proof of quite a different slogan. In almost every case, a country rescued itself by abandoning the gold standard, and the sooner it got rid of gold, the better it did. That would, of course, be true, during a period of concealed deflation where exuberant economic growth exceeds the expansion of gold supplies. A serious weakness of the gold standard has certainly been identified, leading to expressions like barbarous relic and crucifixion on a cross of gold. But there is the other, time-honored, side of it; since the beginning of history, governments have been tempted to inflate the currency in order to dishonor their debts. Governments will do so again at the first opportunity. Without the discipline of a gold standard, the only dependable defense against the catastrophe of hyperinflation is now the courage of the Federal Reserve, and the rather faint hope that we have learned everything about monetary policy that is important to learn.

REFERENCES

| Herbert Hoover: The American Presidents Series: The 31st President, 1929-1933: William E. Leuchtenburg, ISBN-13: 978-0805069587 | Amazon |

Quaker Mary Dyer and Algernon Sydney

Marian B. Sanders, Quaker Activist, 87

|

| Pre K Group |

Marian Binford Sanders, 87, of Mount Airy, a former principal of Lansdowne Friends School who devoted her life to Quaker service, died following gallbladder surgery April 23 at Chestnut Hill Hospital

Mrs. Sanders headed Lansdowne Friends from 1975 to 1981. During that time, her husband, Edwin, was a director of Pendle Hill, a Quaker study center in Wallingford, where the couple lived and where she taught courses. In the early 1980s, the couple lived at Cambridge Friends Meeting in Massachusetts, where they ministered and supervised the facilities.

|

| Chestnut Hill |

After retiring to Chestnut Hill in 1985, according to her son, David, Mrs. Sanders lectured on the poet William Blake at Pendle Hill, taught adult literacy, and cared for her husband, who had Alzheimer's disease, until his death in 1995.

She was dedicated to the concept of world citizenship, her son said and opened her home to students and travelers from around the world. In 1997, she received an award from Earlham college in Indiana honoring her and her late husband for the "55 years of the shared struggle for human justice, for an end to war ... and for broad service in the Society of Friends."

Mrs. Sanders grew up in Dayton, Ohio, and Butler, Pa. She earned a bachelor's degree from Earlham College and, in 1939, the year she married, a master's degree in English literature from Pennsylvania State University.

In 1940, her husband, a Quaker pacifist, was sentenced to federal prison for a year for refusing to register for the draft. After he was paroled, the couple taught at Pacific Ackworth Friends School in Temple City, Calif., which they helped found. For more than a year in the 1960s, they trained teachers in Kenya. Later, Mrs. Sanders taught English literature in Russia as an exchange teacher with the American Friends Service Committee.

In addition to her son, David, she is survived by sons Michael, Richard, John, Robert, and Erin; a daughter, Beth Sanders-Blevins; eight grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

A memorial service will be at 3 P.M. June 26 at Pendle Hill 338 Plush Mill Rd., Wallingford.

Memorial donations may be made to Lansdowne Friends School, 110 N. Lansdowne Ave. Lansdowne, Pa. 19050.

-Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 2004

George Willoughby, 95, Peace Activist

|

| George Willoughby |

Age was nothing but a number for 95-year-old peace activist George Willoughby of Deptford. His worldwide antiwar protests and nonviolent teachings started when he was in his mid-40s and continued until just weeks ago.

Mr. Willoughby was planning a six-week trip this month to India to meet friends he had made during visits to the birthplace of his idol, Mohandas K. Gandhi, and probably to give some of his trademark peace talks.

But Mr. Willoughby died at home of heart failure Jan. 5, a month short of the journey.

A Quaker who led local protests and famous treks from San Francisco to Moscow and from New Delhi to Beijing, Mr. Willoughby recruited many advocates for nonviolent conflict resolution, said a friend and member of the Central Philadelphia Meeting, Nicole Hackel.

"Once you experienced him, you didn't forget him," Hackel said, adding that she became a Quaker in the 1970s because of Mr. Willoughby's influence. "George would engage in conversation with anyone, even a 5-year-old who was attending a meeting for the first time."

Mr. Willoughby became a household name for area Quakers after he became director of the Central Committee of Conscientious Objectors in Philadelphia in 1954. He soon was a frequent presence in the news, mostly under headlines with the words peace, marchers, and protest.

In 1958, Mr. Willoughby was one of five crewmen on the sailboat Golden Rule who received 60-day jail sentences in Honolulu for trying to sail to the area of the Pacific Ocean where the U.S. government was testing nuclear bombs in the atmosphere.

That was Mr. Willoughby's first of many incarcerations, said his son, Alan.

"The Society of Friends in Honolulu brought him a lot of decent food. . . . He always spoke highly" of the Hawaii jail experience, his son said with a slight laugh.

Two years later, Mr. Willoughby organized a dual-continent march to protest nuclear testing. Protesters in groups of about a dozen each covered six countries in 10 months between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Mr. Willoughby joined the group in Poland. Soviet officials stopped them 100 yards short of the Lenin-Stalin tomb in Moscow's main square, according to reports at the time. Instead of delivering speeches, the group was forced to stand in the square in a silent vigil.

In 1963, Mr. Willoughby embarked with about a dozen others on what he intended to be his longest hike - 4,000 miles from New Delhi to Beijing to promote peace between India and China.

Before his journey, a Philadelphia Evening Bulletin reporter asked whether there was a better way than marching to bring about peace.

Mr. Willoughby responded: "Most people of these countries walk; we can reach them. Even if it does no good at all, it is worth it. It's an idea I believe in, and if it produces fruit, so much the better."

After eight months of walking, Mr. Willoughby and company were stopped at the India-China border and barred from crossing into China.

In the next three decades, Mr. Willoughby's projects included the formation of A Quaker Action Group, which opposed the Vietnam War, in 1966; the Life Center Community in West Philadelphia, a training and campaign center for nonviolence, in 1971; and Peace Brigades International, a human-rights group, in 1981.

One of his most memorable contributions to South Jersey, family and friends said, was the creation of the Old Pine Farm Natural Lands Trust, 45 acres of natural conservancy in Deptford.

In his later years, Mr. Willoughby received honors around the world for his peace work, such as the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation award in 2002 in Mumbai, India, which recognizes those who promote Gandhi's ideas and values.

Born in Cheyenne, Wyo., Mr. Willoughby spent much of his childhood in the Panama Canal Zone, where his father worked in construction.

Mr. Willoughby was part of his high school's JROTC program, but, according to friend and biographer Gregory Barnes, he quickly realized the military was not for him.

A family rift led Mr. Willoughby to live in Des Moines, Iowa, with a family friend, Elinor Robson. In the 1930s, he received three degrees in political science, including a doctorate from the University of Iowa.

In 1940, Mr. Willoughby married Lillian Pemberton, a "birthright Quaker" he met in college. By 1944, he became a Quaker, fully immersed in the Religious Society of Friends' beliefs and ideologies.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Mr. Willoughby worked for the Des Moines office of the American Friends Service Committee before moving to Philadelphia with his wife and their four children.

After bypass surgery in 2000, Mr. Willoughby had to slow down. He wasn't able to participate in as many marches and rallies as he would have liked, his son said, but he remained active online.

One of Mr. Willoughby's last protests was in March 2003, an organized obstruction of the entrance of a federal building in Philadelphia to protest the war in Iraq. He took photos of his 89-year-old wife getting her head shaved as part of the demonstration.

"I've never seen her like that, but I like it," he told a reporter. Lillian Willoughby died last year.

One of Mr. Willoughby's last speeches was at Scattergood Friends School in Iowa a few months after his wife's death. He took a road trip with Hackel and one of his daughters to the Scattergood refuge camp's 70th-anniversary reunion, which was held at the school.

Once there, Mr. Willoughby did what he did best: talk. "He just fascinated the young people there," Hackel said.

Some of Mr. Willoughby's last words of advice were: "It is the duty of the opposition to oppose," his son said. "He thought it is your duty to speak up . . . for what you believe is right."

In addition to his son, Mr. Willoughby is survived by daughters Sally, Anita, and Sharon and three grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday at the Friends Center at 15th and Cherry Street

21 Blogs

William Penn, Excellent Lawyer, Terrible Businessman

William Penn was the central force in the establishment of a religion, Quakerism, certain central features of the legal system, three colonies of America, and many of the central concepts of Constitutional Law. He leaves us over three thousand documents, but it remains very hard to form a picture of what he was like.

William Penn was the central force in the establishment of a religion, Quakerism, certain central features of the legal system, three colonies of America, and many of the central concepts of Constitutional Law. He leaves us over three thousand documents, but it remains very hard to form a picture of what he was like.

Tom Paine: Rabble-Rousing Quaker?

Tom Paine is the one who mainly set the fires of revolution burning, and Franklin sent him here, got him a job, circulated his pamphlets. In spite of Franklin's sponsorship, Washington would cross the street to avoid Paine, and fellow Quakers would have no part of his violence. His later life showed him to be a rebel without a cause.

Tom Paine is the one who mainly set the fires of revolution burning, and Franklin sent him here, got him a job, circulated his pamphlets. In spite of Franklin's sponsorship, Washington would cross the street to avoid Paine, and fellow Quakers would have no part of his violence. His later life showed him to be a rebel without a cause.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

Sometimes it's hard for others to understand what makes Quakers tick.

Sometimes it's hard for others to understand what makes Quakers tick.

Edward Hicks: Peaceable Kingdoms

This uneducated Bucks County farm boy has steadily risen in reputation as a painter of primitive art, just as he and his cousin have become spiritual leaders of non-dogmatic religious thought.

This uneducated Bucks County farm boy has steadily risen in reputation as a painter of primitive art, just as he and his cousin have become spiritual leaders of non-dogmatic religious thought.

The Quaker Who Would Be King

Two Americans, Josiah Harlan, and George Bush conquered Afghanistan, and for centuries others who tried it got massacred. Harlan, a Chester County Quaker farm boy with more brazenness than Alexander the Great, died in San Francisco while impersonating a physician.

Inazo Nitobe, Quaker Samurai

One of the most revered leaders of modern Japan was a converted Samurai, married to a Philadelphia Quaker. His father was an advisor to the Emperor, a family of famous warriors.