3 Volumes

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

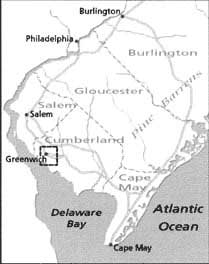

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

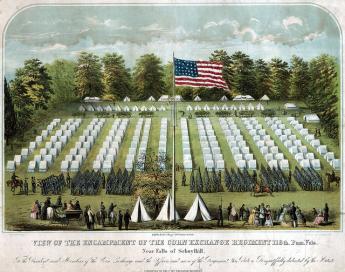

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

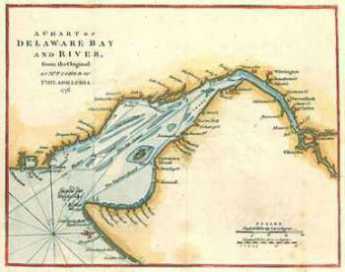

City of Rivers and Rivulets

Philadelphia has always been defined by the waters that surround it.

New Phillies Stadium

|

| Phillies Stadium |

Built to house the Dempsey Tunney prize fight, we have seen six stadiums built there in one lifetime, a seventh in prospect, and three torn down. Building stadiums well are not the same as playing sports well, just as buying cameras is not the same hobby as taking photographs. In both cases, it is possible to get confused as to what hobby you are trying to excel in. Anyway, we have just opened stadium number six, for baseball, named Citizens Bank Stadium.

The new baseball park holds 43,500 spectators, and recently it fills to capacity. There are four or five million people in the region, so if everybody goes there just once to see what it looks like, it should stay full for four or five years. On the days of baseball home games, that is, since it is dead empty for away games, and on days when football and basketball are played in the nearby stadiums dedicated to those sports.

|

| Veteran's Stadium |

That is, at best it will be empty most of the time. New tickets will be $90 apiece in really choice sections, not to mention the corporate boxes, and the ordinary first-class tickets will be $40. The most expensive seats in the old, so-called Veteran's Stadium, were $28. You can take that either way. Perhaps we are pricing ourselves out of major league baseball. And perhaps a willingness to fill the stadium at these new prices is a sign we should have built a new ballpark long ago.

The first step in building Citizens Park

|

| Citizens Park |

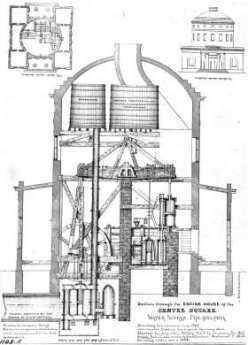

was to dig a big hole in the ground. The playing field ends up twenty-five feet below ground level, so that half of the people who arrive at the park will walk downstairs to their seats, and half will walk upstairs. Never mind; when the game is over, the ones who went down will have to climb up, and the people in the balcony can walk down. That's pretty fair. Of more concern is the water level of the former swamp between two rivers. It was necessary to put in a powerful set of pumps to keep the stadium from turning into a lake. If the power goes out for any extended duration, some interesting photographs could emerge.

It's reassuring to know that the Veteran's was built along the same principles.

|

| Vet Stadium Implosion |

When the Vet was famously imploded into a pile of rubbish, the disintegrated remains of the stadium didn't quite fill the hole. Here's some forward planning, all right. If we are in the business of constructing serial stadiums, the cost of this hobby is appreciably reduced by incorporating the self-service rubbish removal feature. If there are other features like this one, perhaps this stadium collecting hobby isn't as expensive as it sounds.

Germantown Nurses the Yellow Fever, 1793

|

| Yellow Fever, Phila |

The French Revolution continued from 1789 to 1799 and created the opportunity for a second revolution in the New World which a second overstretched European country would lose. The slaves of Haiti just about exterminated the white settlers, except for the few who escaped, taking Yellow Fever and Dengue with them. Both diseases are mosquito-borne, so they flare up in the summer and die down in the winter, although the Philadelphians who welcomed the exiles didn't know that. Yellow Fever in Philadelphia was bad in 1793, came back annually for three more years, and flared up once again in 1798. It could be easily observed to be more frequent in the lowlands, absent in the hills. Seasonal, it reached a peak in October, disappeared after the first frost. In the early fall, people died a horrible yellow death, jaundiced and bilious.

|

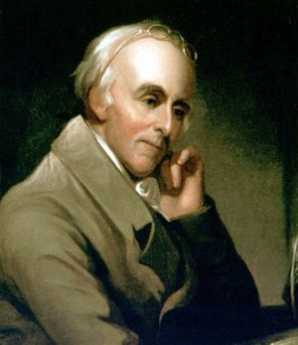

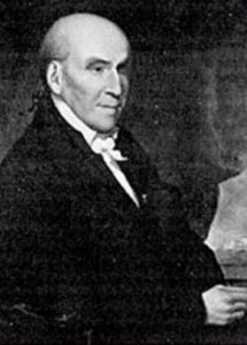

| Dr. Rush |

The Yellow Fever epidemic had a profound effect on many things. It was one of the major reasons the nation's capital did not remain in Philadelphia. It made the reputation of Dr. Benjamin Rush who announced a highly unfortunate treatment -- bleeding the victims -- thus provoking numerous anti-scientific medical doctrines based on the relative superiority of doing nothing at all. In Latin, Galen had capsulized the doctrine of Hippocrates in the "Epidemics" as premium non-nocere ("At least do no harm.") It took a full century for American scientific medicine to recover from this blow to its reputation. Whatever criticism Rush may deserve for his Yellow Fever blunder, it definitely is not true that he was a scientific lemon. Medical students are regularly surprised to learn that he is the physician who first identified and described the tropical disease of Dengue, or "break-bone fever", which was a somewhat less noticed feature among the Haiti exiles in Philadelphia. In still other scientific circles, Benjamin Rush is often referred to as the "Father of American Psychiatry". He was one of the founders of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the oldest medical society in North America. Medical colleagues who today scoff at the yellow fever episode seem to forget that Rush stayed behind to tend the sick during a devastating epidemic, while many of his more cautious colleagues fled for their lives. An unhesitating signer of the Declaration of Independence, whatever Rush did, he did courageously. Non-academic physicians have sarcastically referred to this episode ever since, as proving that "some people" think it is "better to publish than to perish".

One very good non-medical thing the Yellow Fever epidemic accomplished was to put an abrupt end to the torch-light parades of window-breaking rioters agitating, with Jefferson's approval, for an American version of the guillotine and the terror. Federalists like John Adams and William Bingham never forgave Jefferson or his admirers for this, so the class warfare movement might likely have got much worse if everyone had not suddenly dropped tools, and headed for the hilly safety of Germantown.

The President of the new republic, George Washington, was in Mt. Vernon in the summer of 1793, wondering what to do about the Yellow Fever epidemic, and particularly uncertain what the Constitution empowered him to do. He finally decided to rent rooms in Germantown and called a cabinet meeting there. His first rooms were rented from Frederick Herman, a pastor of the Reformed Church and teacher at the Union School, although he later moved to 5442 Germantown Ave, the home of Col. Franks. Jefferson chose to room at the King of Prussia Tavern.

During this time, Germantown was the seat of the nation's government. As was fervently hoped for, the cases of yellow fever stopped appearing in late October, and eventually, it seemed safe to convene Congress in Philadelphia as originally scheduled, on December 2.

Although Germantown was badly shaken by the experience, it was a heady experience to be the nation's capital. Meanwhile, a great many rich, powerful and important people had come to see what a nice place it was. Germantown then entered the second period of growth and flourishing. Walking around Germantown today is like wandering through the ruins of the Roman forum, silently tolerant of visitors who would have never dared approach it in its heyday.

REFERENCES

| Benjamin Rush: A Discourse delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Thomas A. Horrocks ASIN: B0006FCBXS | Amazon |

| Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague Of Yellow Fever In Philadelphia In 1793: J.H. Powell ISBN-13: 978-1436715881 | Amazon |

| Germantown and the Germans: An Exhibition from the Collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia: Edwin, II Wolf ISBN-13: 978-0914076728 | Amazon |

John Bartram's Garden

|

| Bartram Gardens |

It's worth a visit to Bartram's Gardens, if only for the astonishment of finding a very large farm and stone Quaker farmhouse within a few blocks of our largest medical center, a stone's throw from the biggest oil refinery on the upper East Coast. And located on the edge of a neighborhood that is, well, past its prime. The trees on the farm are centuries old, so walking around the grounds imparts the feeling of being hundreds of miles from civilization when in fact you are only a hundred yards away from streets that are very urban, indeed. When you turn in certain directions, an occasional skyscraper peeps over treetops, and down the meadows, at the farm's dock on the leafy-banked Schuylkill, you can see oil storage tanks across the river, just a long shot with a 2-iron away. Look upward, to see the upper half of shining towers of Center City.

The farm property as it now stands dates back to 1728, but the site marks the earliest beginnings of the city, nearly a hundred years earlier. The river curves around this hill then snake on down to Delaware through flatlands which were originally swamps ("wetlands", as they say). The hill is as far downriver into malaria territory as the Indians were willing to go, so the Dutch traders had to sail upriver and dock there in order to take thirty or forty thousand fur pelts back to Holland each year. One thing or another has been dumped on the swamps for three hundred years, and the oil companies found it a cheap place to buy enough land for their refineries, close to four or five railroads near Bartram's place, and with access to the high seas. Right now, most of the oil comes from Nigeria, emptying two or so supertankers a week. There has to be enough storage capacity to take care of delays caused by bad weather on the Atlantic, and there has to be access to railroads and highways to carry the finished product away. The rest of a refinery is just thousands of miles of metal pipes, gleaming in the sun.

Sun Oil is trying to be a good neighbor, turning more and more of the area over to nature preserve, as chemical engineers have learned how to work in a smaller space with fewer employees. The banks of the lower Schuylkill are now mostly grown to shrubs and trees, concealing from boat travelers the rather extensive dumps of old auto tires and similar refuse. It's a placid winding trip, increasingly coming to resemble what the Dutch traders once encountered. Especially in May, when the Palomino or Empress trees are in purple bloom. It seems the Chinese packed their porcelains in dried Palomino seed pods, and the discards have grown up to quite a nice display. Logan Square is filled with such trees, quite artfully pruned and maintained; just imagine several miles of the river lined with them, and you can see why the Tourist Bureau is excited about the potential. If you have been to San Antonio you know the potential of an urban river ride, which in this case might go all the way up to the Art Museum. Given enough public response, you can envision two or three-day barge rides from New Castle, Delaware to Pennsbury, with side trips up past Bartram's to the Waterworks. Right now, trips are comparatively limited by the tides, with a few trips a year down from Bartram's to the refineries, and a few more up to the river to the Art Museum. They use floating docks, and permanent docks will need to be built.

|

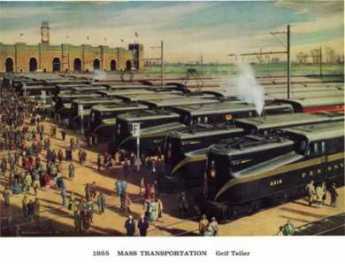

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

Originally, the crude oil came from upstate Pennsylvania, near Bradford, and was the main source of the dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Baltimore and New York were also the beginnings of transcontinental railroads, but their freight cars came back empty. The upstate Pennsylvania oil gave the PRR a dominant edge by supplying cargo for two-way revenue.

When George Washington had to retreat from the Battle of Brandywine, the armies had to cross the wetlands, and the river, to get to Philadelphia. Washington got there first and burned the boats after his army got across. He knew, but the British probably did not fully realize, that the first place to ford the Schuylkill was at Norristown. When the British finally got that far, Washington was waiting for them, but a fall hurricane came along and soaked everybody's gunpowder before there could be much of a battle. Unfortunately, Mad Anthony Wayne was unprepared for a nighttime bayonet charge, and there was still quite a slaughter.

You can't wander around John Bartram's house and gardens without getting the impression of considerable wealth. Bartram was interested in botany, becoming the most eminent authority on plants of the Western hemisphere, a very close friend of Benjamin Franklin, and probably the main force behind the creation of the American Philosophical Society. But although Bartram was a hobbyist, he was a shrewd businessman, selling curiosity plants to Europeans, and commercially improved fruits and vegetables to local farmers. There are still some Bartrams around Philadelphia, with a strong Quaker air about them. Around 1850 the place was sold to a zillionaire railroad magnate named Eastwick, who fixed up the place in the high style he learned building the railroads of Russia for the Tsar. The mansion has been torn down, but the stone farmhouse, stone barn, stone sheds, stone outbuildings, stone everything -- endures, like many of the curiosity trees and bushes. Well worth a visit.

Lambertville and Lewis Island

|

| Atlantic Shore Railroad |

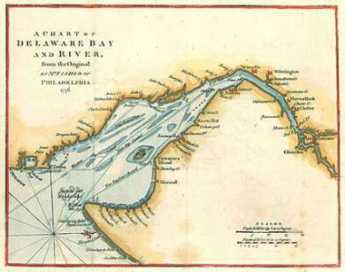

Recall that open Atlantic shoreline once stretched from Perth Amboy to New Castle, Delaware. Glaciers pulverized the nearby mountains and dumped a huge moraine of sand into the ocean, creating southern New Jersey as an offshore island in geological times. The bay silted up and eventually attached that island to New Jersey. The silting-up probably would have continued for another sixty miles, making Philadelphia a land-locked inland city, except that the true

|

| Delaware River |

Delaware River came tumbling down from the mountains to Trenton, turning sharply right and then maintaining an open shallow channel to the sea. From Lambertville to Trenton, the river drops over a series of small falls or rapids, easily visible except when heavy rains "drown" them.

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

So, geography accounts for the scenery and early history of the upper end of Delaware Bay. It's still a beautiful hilly countryside with small antique villages, sparsely populated in spite of two nearby cities. Water power at the Fall Line, and then anthracite from the upstate mountains once encouraged early industry in an area that was rather poor farm country. But the Pennsylvania Railroad then rearranged commerce so that a blossoming New Jersey industrial area withered into quaintness. The early railroads mostly all ran East-West along the rivers, since investors in Atlantic port cities obtained both finance and protection from their state legislatures; railroads had almost reached the Mississippi before any were able to establish North-South connecting spurs. A seaboard trunk line was almost impossible to imagine. Finally, a consortium organized by

J.P. Morgan bullied through the main trunk line running through the bituminous coal areas of Pennsylvania and on to the West, with the major port cities connected by the great Northeast Corridor of the Pennsy. This corridor would run on the Pennsylvania side of Delaware. Industry on the bypassed New Jersey side would just wither and decline, and eventually so would the anthracite cities. Since the original colonies and states all ran from the ocean to the interior, each had a vital political interest in resisting this outcome. Only a strong and brutal corporation could bring it off.

When George Washington was circling around Trenton to attack it on Christmas, a narrow spot up-river with a dozen houses on either side was called Coryell's Crossing or Ferry. That's now Coryell Street in Lambertville, linked to the other side of the river at New Hope, after first crossing a narrow wooden bridge to Lewis Island, the center of shad fishing, or at least shad fishing culture.

The Lewis family still has a house on Lewis Island, and they know a lot about shad fishing, entertaining hundreds of visitors to the shad festival in the last week of April. The river is cleaning up its pollution, the shad are coming back, but they, unfortunately, took a vacation in 2006. At the promised hour, a boatload of men with large deltoids attached one end of a dragnet to the shore, rowed to the middle of the river, floated downstream and towed the other end of the net back to the shore. The original anchor end of the net was then lifted and carried downstream to make a loop around the tip of Lewis Island, and then both ends were pulled in to capture the fish. There were fifty or so fish in the net, but only two shad of adequate size; since it was Sunday, the fish were all thrown back.

But it was a nice day, and fun, and the nice Lewis lady who explained things knew a lot. Remember, the center of the river is a border separating two states. You would have to have a fishing license in both states to cross the center of the river with your net; game wardens can come upon you quickly with a power boat. But the nature of fishing with a dragnet from the shore anyway makes it more practical to stop in the middle, where shotguns from the other side are unlikely to reach you. An even more persuasive force for law and order is provided by the fish. Fish like to feed when the sky is overcast, so there is a tendency on a North-South river for the fish to be on the Pennsylvania (West) side of the river in the morning, and the New Jersey (East) side in the evening. During the 19th Century when shad were abundant, work schedules at the local mills and factories were arranged to give the New Jersey workers time off to fish in the afternoon, while Pennsylvania employers delayed the starting time at their factories until morning fishing was over.

Somehow, underneath this tradition one senses a local Quaker somewhere with a scheme to maintain the peace without using force. Right now, there aren't enough fish to justify either stratagem or force, but one can hope.

Life On The River (3)

|

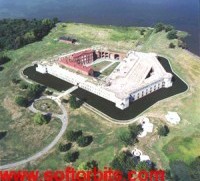

| Darth Mouth Castle |

All over Europe the scene is repeated: a market town and seaport at the mouth of a river, with many miles of riverbank castles in the hinterland. The seaports had to be fortified against pirates, the hinterland against marauding brigands. But the two flows of commerce consisted of baronies upriver feeding the seaport, while secondarily their seaports carried on trade with nearby river-organized economies. From time to time, someone like Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Bismarck or Hitler would try to unify the various river economies, usually unsuccessfully. In fact, the same pattern was seen along the Pacific Coast of South America, until the Incas figured out how to go along the mountain ridge in the far interior, and then come down the rivers from the sparsely populated areas to the maritime settlements at the mouth of the river, whose defenses were planned for enemies from the sea. Philadelphia followed the commercial pattern, but without fortresses and castles.

Because of the vagaries of King Charles II, and underneath that, because of marshes and their mosquito-borne diseases, the Delaware Bay was settled fairly late in colonial times -- and almost entirely by Quakers. The Dutch were interested in fur trading rather than settlement, the Dutch were anyway too few, their sovereign too indifferent, and William Penn took care of the Indians. So the English settlers had no one to fight except other Englishmen, once the French stab at Inca-like strategy was put down in 1753. After 1783, or perhaps 1812, the world finally left us alone. The Delaware Bay and River are essentially free of fortresses, Philadelphia has no castles. The peaceful sixty miles of upper Delaware Bay became lined with big farmhouses, or big Federalist and Victorian mansions. For a century, from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War, and even for a time after that, the history of this peaceful pond reads like a novel by Jane Austen.

As a playground for menfolk, it would be hard to improve on Victorian Delaware Bay. The river was full of fish, notably shad. In the fall, the migrating ducks and geese made for marvelous hunting. In the countryside behind the riverfront, houses were found all the sports having to do with horses; fox hunting, racing, horses shows. The kids could putter around in small sailboats, the adult sailors could sail a yacht to Europe if they wanted to. After John Fitch invented the Steamboat, it was possible to take a daily commute to the best male game of all -- trading, investing and gambling in the financial and commercial center of Philadelphia.

|

| Shad |

Marion Willis Rivinus and Katherine Hansel Biddle wrote a little book in 1973 called Lights Along the Delaware which tells the river story from the female point of view. The woman of the house was sort of the mayor of a little city, organizing the staff, supervising the garden, educating the children, planning the household, and organizing the dinners and social events. Educated and trained to the role, she knew what to do and enjoyed doing it. Jane Austen wrote the handbook. And while the menfolk were essential members of the cast of characters, women were the managing directors. The men were off with their horses, or sailboats, or fishing rods, or their faraway big-deal mergers and acquisitions. True, it was not a notably intellectual community, there was no Edith Wharton, Abigail Adams or Emily Dickinson. You might find some of that in Germantown, perhaps. The professions, law, and medicine, lured the more studious male members away from Society, but the international diplomatic circle was seen as the ideal career for any truly graceful graduates of this environment.

|

| Riverbank Railroad |

As the riverbank was gradually destroyed by railroads and expressways, only a few mansions like Andalusia remain in good repair. Curiously, what endures best are the clubs. The fishing club variously called the Fish House, the Castle, the Colony in Schuylkill, or the Schuylkill Fishing Company of the State in Schuylkill, has moved as many times as the name has changed. Started in 1732, it is the oldest continuously existing men's club in the world. It moved to the Delaware River from the Schuylkill when the Fairmount dam was built, and to its present location at Devon, the estate of William B. Chamberlain in 1937. New members do the cooking, cleaning, and serving, older members tell stories. When the river pollution is finally controlled, they may go back to catching the fish as well as cooking them. There's the Philadelphia Gun Club, which before 1877 was the Public Holiday Shooting Club of Riverton NJ. And then there's the Gloucester (NJ) Fox Hunt, which during the Revolution turned into First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry. After escorting George Washington to the battles of Boston Harbor, The Troop has been an active fighting unit of the National Guard (most recently in Bosnia) as well as a devoted center of male horsemanship between wars. The Farmer's Club, the Agricultural Society, and the Horticultural Society all reflect the rural interests that once predominated just behind the riverfront estates, still thriving aloof after 150 years of suburbia, exurbia and urban revival.

|

| Philadelphia Gun Club |

Although the riverfront industrial slums which destroyed the Philadelphia branch of Jane Austen's gracious living subculture are themselves declining and seem about to go away, it would take a real visionary to imagine how the Grand Life on the River will ever return. The banks of Delaware are much lower than the bank of the Hudson, for example. They make a great place to put high-speed rail lines and even higher speed interstate highways. The patrons of Hyde Park, West Point, and Poughkeepsie are much higher up a cliff and can overlook the river without much noticing an occasional whoosh. The mansions along Delaware have to look right at the tracks. Except for a few places like Bristol which have become isolated on the river side of the tracks and highway, it's not easy to see how you would get from here to there, or when.

Look Out For That Ship!

Tales of the Sea abound, even a hundred miles from the ocean.

|

We are indebted to the President of the Maritime Law Association of the U.S., Richard W. Palmer, Esq. (who unfortunately died in March 2017 at the age of 97), for both a strange definition and an amusing story. An "allusion" is a collision between a ship and a stationary object, such as a bridge or a dock. As you might imagine, the ship is almost invariably at fault, mainly through errors of the pilot, although hurricanes and other severe weather conditions can make a difference. Moving ships have been running into stationary objects for many centuries, and almost every allision contingency has been explored. Ho hum for maritime law.

The Delair railroad drawbridge over the Delaware River at Frankford Junction is just a little different. It was built in 1896 when the Pennsylvania RR decided it needed to veer off from its North East Corridor to take people to Atlantic City. For reasons relating to the afterthought nature of the bridge, the tower for the drawbridge is located half a mile away, out of a direct vision of the ships going through. Also, a late development in the history of the river was the construction of U.S. Steel's Morristown plant, bringing unexpectedly huge ore boats from Labrador to the steel mill. The captains of the ships pretty much turned things over to the river pilots, for the last hundred miles of the trip.

|

| Delair Railroad Drawbridge |

Shortly after this iron ore service was begun, the inaugural ore boat Captain had a little party with some invited guests. So it happened that the Commandant of the Port, the Admiral in Charge of the Naval Yard, and other equally high ranking worthies like the head of the Coast Guard were on the bridge of the ore boat, taking careful notes of the procedure.

The ship tooted three times, the shore answered back with three toots. In real fact, they were connected by ship-to-shore telephone for most of the real business, but this grand occasion called for an authentic nautical ceremony. Three toots, we're approaching your bridge. Three toots back, come ahead, the coast is clear. The admirals scribbled it all down.

As the ship approached the point of no return, beyond which it could no longer stop or turn in time to avoid an "allusion", the people on the bridge were appalled to see a train crossing the bridge ahead. Several toots, loud profanity on the ship to shore phone.

No worry, answered the bridge, we'll lift the drawbridge in plenty of time. But half a minute later the bridge controller made the anguished cry that the drawbridge was apparently rusted and wouldn't open, to which the captain shouted, "This ship is going to take away your blankety-blank bridge and sail right through it".

At this point, the pilot took matters into his own hands, and violently threw the rudder hard left, swinging the ship sideways, soon nudging the bridge with some damage, but nothing like the damage of a head-on allision. The lawsuit, as one might imagine, was the outcome.

The attorneys for the railroad were pretty high-powered, too, and had piles of legal precedents to cite. But they were quite unprepared for Dick Palmer to put the Commandant of the Port on the witness stand, reading slowly and painfully from his very detailed notes about the conversations on the bridge, about the approaching drawbridge.

And so, Philadelphia can now claim to have experienced one of the very few instances where a ship ran into a bridge -- and the court found the bridge to be entirely at fault.

Nature Preservation

|

| Former Local Resident |

Although Philadelphia is proud of its history and its historical buildings, it would be my observation that Philadelphia is not as intense about the preservation of Nature as some other parts of the country appear to be. Philadelphians like nature all right, but it tends toward azaleas a little, and only infrequently do you meet someone in our town who could fairly be sneered at as a tree-hugger. In fact, I believe I sense it being implied that non-Philadelphians are so impassioned about minnows and spotted owls because they have no old houses to be worked up about. But perhaps I only read that into their unguarded remarks.

It must be admitted that some efforts to preserve nature have had unintended consequences. In the Serengeti region of Africa, a grassland between Kenya and Tanzania, about two million animals migrate in great herds, following the equatorial rainfall. The zebra and gnu are the main herds, with lions and leopards lurking around the edge, and vultures in the trees and hyenas and baboons further out, waiting for something edible to stumble. Several dozen jeeps and land rovers carry the tourists around to see the fun. It's a Disneyworld for American tourists. It's a little disquieting to learn that the local government sends helicopters around to machine-gun the poachers, and thus it's a little disturbing to think that starving people are being shot for the benefit of the tourist trade, if not for the tourists personally. Perhaps it doesn't matter, because most of the locals will be dead from AIDS in ten years, but most of the tourists who hear these arguments rehearsed fall strangely silent.

|

| Eagle Nest |

And then, back in old Philadelphia again, a lady at an Athenaeum reception was telling her circle of friends about an eagle's nest that appeared on her country place, but don't tell anyone. The nest last year was as big as a Volkswagen, this year it's as big as a Subaru, but don't tell anybody about it. Well, why not? Her husband quickly intervened to relate that the laws protecting the bald eagle and its nests are so severe that people for several miles around such a nest are bound by terribly onerous restrictions and subject to strict penalties. So? Well, the people who have been annoyed by these unwelcome laws will sneak in and shoot the eagle, just to get rid of the whole nuisance. So, the laws intended to protect our symbolic national birds actually have the effect of provoking their slaughter.

It's my view that these stories with an unspoken moral reflect discomfort with having people in one region of the country promote laws which mainly affect people in some other part of the country. We don't want people in Oregon to introduce legislation regulating the restoration of Society Hill buildings. So, we are not quick to support legislation regulating the drilling for oil in that remote mosquito-infested swamp called the Arctic Wildlife Preserve, when we hear that the local Alaskans are cool to the idea. It begins to sound like R versus D, so let's dance away from the topic. If there's some way to let Alaskans decide what's good for Alaska, maybe it's better.

The Delaware valley had been settled by Europeans for sixty years before William Penn arrived. Roughly, fifteen years of the Dutch, followed by fifteen years of Swedes, fifteen years of Dutch again, fifteen years under the English Duke of York. There were over a thousand people living here who spoke Swedish. With a focus on what the environment was like and how the early settlers treated it, listen to a passage from The Making of Pennsylvania by Sidney George Fisher.

The woods at that time were quite free from the underbrush and afforded a short nutritious form of grass. It was easy to ride on horseback anywhere among the trees. But the second growth, which came after cutting or burning the primeval forest, brought on the underbrush and destroyed the woodland pasturage.

The Swedes never attempted to clear the land of trees. They took the country as they found it; occupied the meadows and open lands along the river, liked them, cut the grass, plowed and sowed, and made no attempt to penetrate the interior. But as soon as the Englishman came he attacked the forests with his ax, and that simple instrument with a rifle is the natural coat-of-arms in America for all of English blood. In nothing is the difference in nationality so distinctly shown. The Dutchman builds trading posts and lies in his ship offshore to collect the furs. The gentle Swede settles in the soft, rich meadowlands, and his cattle wax fat and his barns are full of hay. The Frenchman enters the forest, sympathizes with its inhabitants, and turns half savage to please them. All alike bow before the wilderness and accept it as a fact. But the Englishman destroys it. There is even something significant in the way his old charters gave the land straight across America from sea to sea. He grasped at the continent from the beginning, and but for him, the oak and the pine would have triumphed and the prairies still are in possession of the Indian and the buffalo.

Nevertheless, the Swede seems to have lived a very happy and prosperous life on his meadows and marshes. He was surrounded by an abundance of game and fish and the products of his own thrifty agriculture, of which we can now scarcely conceive. The old accounts of game and birds along Delaware read like fairy tales. The first settlers saw the meadows covered with huge flocks of white cranes which rose in clouds when a boat approached the shore. The finest varieties of fish could be almost taken with the hand. Ducks and wild geese covered the water, and outrageous stories were told of the number that could be killed at a single shot. The wild swans, now driven far to the south and soon likely to become extinct, were abundant, floating on the water like drifted snow. Onshore the Indians brought in fat bucks every day, which they sold for a few pipes of tobacco or a measure or two of powder. Turkeys, grouse, and varieties of songbirds which will never be seen again were in the fields and woods. Wild pigeons often filled the air like bees, and there was a famous roosting-place for them in the southern part of Philadelphia, which is said to have given the Indian name, Moyamensing, to that part of the city.

Philadelphia Green

|

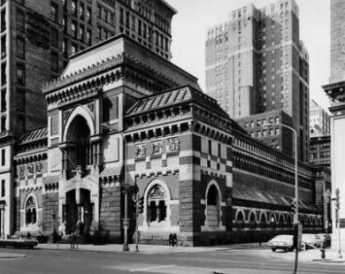

| Pennsylvania Horticultural |

The Philadelphia Flower Show is the best in the country. Getting crowds of visitors every March, it would get even more if Convention Hall were bigger. Obviously, it is a financial success for its owner, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. What six or eight million dollars of profits go for is a city-wide outdoor beautification effort called Philadelphia Green. That, too, is the biggest, oldest and best effort of its kind in the country

About a hundred employees and four thousand enthusiastic volunteers spread out over the City, to make it look half-way decent. As the momentum grows, the political strength grows, too; and politicians notice that. The ladies who run this effort hit the school system pretty hard for volunteers and the enthusiasm of inner-city kids for an activity not often seen in the asphalt jungle is very heartening. The Horticultural Society also hits local businesses with appeals; if flower gardens aren't your thing, just give us the money and we'll do it for you.

Philadelphia Green has created four hundred community gardens, seventy neighborhood parks, planted 20,000 trees in 4 years, and vigorously pursued vacant land management. If the ground is hopelessly covered with concrete they bore holes in it to drain off the water, and pour on enough dirt to get grass to grow. Among the many things which volunteers contribute, novel ideas rank high.

Someone approached the Wharton School, and it is asserted that unbeautified vacant lots are worth 18% less than average, while beautified ones are worth 30% more. Since only 10% of the City's many vacant lots have been cleaned up, there's lots of room for economic improvement in the future. But the improvement is already quite visible, isn't it?

REFERENCES

| Standardized Plant Names: American Joint Committee on Horticultural, Frederick Law Olmsted | Google Books |

Philadelphia Food: Ingredients

|

| Super Market |

There was a time when locally grown farm produce was much more critical than it is at present. There were even resort hotels with their own farms that offered fresh vegetables as the main attraction for vacationers, but now almost any supermarket will supply reasonably good produce to most places in the country. Nevertheless, certain things like fresh corn on the cob must be cooked and eaten almost the same day they are picked, and such seasonal local produce is better around Philadelphia than any other metropolitan area.

|

| Campbell Soup Kids |

The states of Delaware and New Jersey were once Atlantic barrier islands, so the sandy loam is particularly favorable for growing asparagus, for example. An asparagus field is planted as perennials, with new shoots harvested by stoop labor fields of asparagus is difficult to plant and quite valuable once established. Tomatoes are annuals, which in their finest form will continuously produce all summer. It's only worth planting "steak" tomatoes, or so-called Jersey Tomatoes, if there is a local market willing to pay premium prices for the fact that the human picker can tell a green one from a red one. The tomato industry which once supplied Campbell Soup to the world has now mostly moved to California where improved varieties of soup-grade tomatoes all ripen simultaneously, thus can be harvested with machinery at a single pass. Lancaster County in Pennsylvania boasts the best topsoil in the country, although it must be admitted that the glaciers dumped topsoil fourteen feet deep around northern Illinois. Such topsoil is almost too valuable to be used for truck gardens. Lancaster County grows fodder for cattle, and the cattle are hidden away in barns where passersby never see them, just as you never see chickens when you drive through Delaware. What visitors see are silos in Lancaster County and chicken sheds in the lower counties, and acres and acres of animal-feed crops (field corn and soybeans) surrounding the farms. A century ago, all those Swamps("wetland") around Delaware Bay held lots of ducks, geese, quail, and other game, but the game is less popular than it used to be. Location, location is always the true source of value, and in this case, the source of good Philadelphia food is the local location of a vast variety of fresh produce.

|

| Brandywine Battlefield |

Somewhere, the story needs to be retold of the mushroom growers of Kennett Square. This little nondescript town near the Brandywine Battlefield at the top of the state of Delaware was the mushroom capital of the world. It stayed that way for generations, by keeping the secrets of the mushroom trade a strict family secret. Among the various oddities was the production around Thanksgiving time of the first crop of the season, which were often as large as grapefruit, and usually only given to members of the family or special friends actually to be carved at the Thanksgiving table next to the turkey. During the Second World War, Franklin Roosevelt (his daughter-in-law was Ethel DuPont, who lived nearby) personally appealed to the mushroom farmers to reveal their secret methods to the makers of penicillin, needed for the war effort. The farmers gave it up, penicillin saved thousands of lives. And nowadays, most mushrooms in American supermarkets are grown in Taiwan, flown in at prices the Kennet Square growers cannot match.

Real estate developers are doing their best to fill up those truck gardens with split-level houses, of course, and the lovers of good food are allies of the lovers of the environment. So, the individual householder needs to know how to find the Red, Blue and Green Dot roadside farm stands along the highway to the Jersey shore, when the Jersey corn, tomatoes, and melons are at their best, or earlier in the year when Jersey berries are available. You need to know about the Reading Terminal Marketplace, the South Philadelphia street markets, the ethnic neighborhood butcher shops and bakeries, the Kutztown Fair and the farmer's markets in Lancaster County. It's surprising what you can order over the internet, but for the really choice fresh produce in season, you have to hunt around a little.

The farmers of South Jersey have traditionally been Quakers. One Quaker family named Taylor has had a farm right next to the Delaware River in Cinnaminson, just north of the Tacony Palmyra Bridge, since the days of William Penn. Taylors signed the 1783 minute of the Yearly Meeting of Quakers to the Continental Congress, advocating an end to slavery. As the Cinnaminson area became built up, the Taylors had a thriving fruit and vegetable stand, which was left unattended. That is, Joe Taylor brought out the corn and other produce and left it on the stand, while the customers just came up and left their money in a box on the same table. No one stole the money for a century, just as no one in the neighborhood ever locked the door of his house. As things evolved, Joe Taylor, Jr. eventually won the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics for discoveries helping to explain the force of gravity. But in time, the family decided to give up the farm and turned it over to the State as a nature preserve. Undoubtedly a major factor in the decision, if not the only deciding factor, was the repeated discovery that people were stealing the money from the vegetable stand box.

|

| Market on Spruce Street |

For the most part, however, the supermarkets and the chefs of Philadelphia's restaurant revolution nowadays just need to go to the South Philadelphia Food Distribution Center, down in the old filled-in swamp and garbage dump area at the foot of the Walt Whitman Bridge. This is Harry Batten's gift to his city. The former chief of the N.W. Ayer advertising agency made it a personal crusade to put across a remarkable transformation in his home town. Until well past the Korean War, wholesale food distribution took place in the streets of the former Society Hill, never mind how historic it is. Traffic was at a crawl, cartons of vegetables were strewn over the streets, the noise and stench of America's Most Historic Square Mile was a disgrace. The city was persuaded to set aside land for the purpose, and the wholesale grocers were persuaded to move their warehouses to one combined location with rail, bridge, highway and local access. Within months of opening, the wholesale grocery business had moved to the new location, where it became an international marvel. Meanwhile, Charles E. Peterson bought a Spruce Street mansion that once belonged to Stephen Girard from the old Spruce Street Osteopathic Hospital for $8,000.00, rehabilitated it in absolutely authentic style, and moved into the new home, himself. Society Hill Restoration had begun, Philadelphia's restaurant revolution had begun, a great many people became millionaires out of the commercial side of the process, tax ratables soared, tourists poured into the Independence Park area and Penn's Landing and the Camden waterfront. It's been a long time since Harry Batten's name was heard much, but he ought to have a bronze statue sixty feet high. As the Quakers say, you can do anything if you have leadership. And leadership is one man.

Philadelphia Food: Traditional

|

| The Ritz Carlton |

New Orleans is famous for its cooking, and its residents claim it is impossible to get a bad meal in NOLA. New York is famous for its restaurants, where you can get things to eat that are available nowhere else, even though there is lots of bad cooking in that city. Philadelphia is famous for its food, which puts a slightly different twist on the matter. The Delaware Bay provides seafood, the Garden State of New Jersey provides fresh fruit and vegetables, the Pennsylvania Dutch Farm area provides meat and produce, the Diamond State of Delaware is famous for poultry, and lately, the shipping for Chile brings in fruit and vegetables out of normal season. Philadelphia is within easy distance of the very best and freshest of groceries. The city responded with bakeries, meat markets, fish markets, breweries, dairies. One by one, the latest ethnic arrivals brought in new recipes, quickly modified to fit the local style. All of this explains why Philadelphia can be famous for its ice cream, for example, even though it was not invented here as some local patriots carelessly contend.

Snapper soup is certainly one of the traditional Philadelphia dishes. To make it in the traditional way, you have to dedicate a stove for the process. New material is dumped in the top and today's soup is taken out the bottom, imitating the process for making sherry wine. The Old Original Bookbinder's restaurant had such a dedicated stove, but it has gone out of business, apparently leaving the Union League as the only traditional snapper soup source. Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup is pretty much the same as Snapper soup, substituting tripe for the turtle as the meat base.

Scrapple is not to everyone's taste in this age of cholesterol fears, but it is certainly a locally famous dish, usually served as fried slices for breakfast. Scrapple is actually a mixture of cornmeal mush and Pennsylvania Dutch Puddin', a stew of scrap meats which is also sold as a chilled loaf. Puddin' is a dish for real traditionalists who have inherited low cholesterol to protect them from it. Only one or two old stands in the Reading Terminal market still carry it, and then only at butchering season. The Reading and Lancaster farmers markets are a more dependable source for Puddin', and Scrapple survives as more popular because it can be obtained in cans in the supermarkets. While you are there in a farmers market, you might get a loaf of head cheese, which substitutes gelatin for congealed fat as the binder for cooked meat chips with spices. Among the local heavy breakfasts must be mentioned stewed kidneys on waffles. The local belief is that this surprisingly delicious dish was introduced from Virginia, by steamboat vacationers to Cape May who mixed with Philadelphia vacationers at places like the Chalfonte Hotel, where stewed kidneys can/may still be obtained on Sunday morning.

Cinnamon buns, or Philadelphia Sticky Buns, are a local delicacy with the tradition of coming from Saxony in what is now Germany. The more butter and sugar the better, and real Philadelphians fry the sticky buns for breakfast. Out in San Francisco, they are famous for sourdough bread, while in Philadelphia the locally famous bread is black bread, a form of pumpernickel. Unfortunately, it is easily imitated by putting cocoa in white bread, so you need to lift a loaf before you buy it. Real black bread is as heavy as a cannonball, and about the same size and shape; it's even better with raisins in it. Toasted Crumpets are a Scottish introduction to the town's traditions, ambrosial if you can get fresh crumpets. Crumb cake is another traditional breakfast bun, known as coffee cake in the Dutch country, and imitated in commercial form as Tastykake.

|

| Snapper |

When turtles were more abundant, snapper stew, fried oysters and sherry were favorites, but now terrapin is such a rarity that it is saved for special occasions and special guests. It's usually served in a cream sauce in Philadelphia, whereas cream sauce is called abhorrent in Baltimore. Because of the availability problem, the party dish nowadays is apt to be fried oyster and chicken salad, and even oysters are getting a little scarce.

No one seems to challenge the idea that iced tea originated in Philadelphia, and in the Dutch Country, it is quite common to have iced tea 365 days a year, pitcher after pitcher. Let's not forget meatloaf, and corned beef hash with an egg, which is both perfectly delicious when served by someone who knows how to make them. They sound like leftovers, but it depends on where you get them. In the men's clubs, and in some Reading Terminal Restaurants, they are a star feature of the menu.

|

| Shad |

Around March 15, it is a good idea to ask if shad or shad roe is available. The trick is to get the fish with the bones removed. In recent years, shad is increasingly abundant, but it isn't so easy to find a butcher or chef who knows how to excise the bones while leaving the filet intact. At the moment, just about the only place that serves traditional planked shad is the Salem Country Club, out on the tip of the abrupt bend in the river above Salem, New Jersey. The ceremony is to split the big fish and nail it to a board, which is then placed in the open fireplace to cook, snapping and popping while its marvelous aroma fills the dining area. Owen Johnson once wrote a famous Lawrenceville book about The Tennessee Shad, so other towns must enjoy shad, too, but we wouldn't really know.

Special Philadelphia dishes may be a little hard for the tourist visitor to find. If you click on this link , you'll find a website put together by an enthusiast, who lists some of the better places for a wandering tourist to find local specialties. Philadelphia has quite a few high-toned fancy sit-down restaurants, too, but these are cheap, good, and easy to find.

Riverline: Camden and Amboy Revival

The RiverLine, a sort of diesel-powered overgrown trolley car line, has just opened on the Conrail tracks from Camden to Trenton. It runs every 30 minutes in both directions but unfortunately stops at 10 PM to let Conrail run freight trains at night. That's almost a perfect fit for the two operations, although it can leave baseball fans stranded at a night game at Campbell Park, or concertgoers at the Tweeter Center. The trains are running fairly full, partly because of their novelty, and partly because of the initial decision not to collect the $1.10 fare on Sunday, but mostly because the Riverline proved to be a better idea than anyone realized it would be. It's considerably cheaper for Philadelphia commuters to Wall Street to take the Riverline and transfer to New Jersey Transit at Trenton, for one thing. Even Amtrak encourages that, because high gasoline prices have filled up the Amtrak trains.

It's well worth a historical excursion on the RiverLine, which runs on the former right of way of the Camden and Amboy RR, the first railroad in New Jersey, chartered in 1830 by Robert L. Stevens. A genius of many talents, Stevens invented the iron rail which looks like an inverted "T," held in place by a system of plates and broad-headed spikes. The system is still in use today. Stevens also devised the use of wooden cross ties rather than granite ones, finding they resulted in a smoother ride. In 1834, he joined forces with another many-talented genius, Robert F. Stockton, who had earlier constructed a canal from New Brunswick to Trenton. Stevens then built a railroad beside the canal, subsequently extending it from Trenton to Camden. Stockton ran ferry boats from Perth Amboy to New York, and from Camden to Philadelphia. The full trip from New York to Philadelphia took nine hours, a remarkable improvement over the horse-drawn competition. The partnership also got the Legislature to confer monopoly rights, so the arrangement was highly profitable as well as an engineering marvel. Sixty years later, the Sherman Act would declare such monopolies to be crimes, but in 1830 they were considered a clever way for Legislatures to stimulate risky investment. The Pennsylvania Railroad bought the partnership and its monopoly in 1871, but preferred to bridge the Delaware River at Trenton, so the towns and track along the Jersey side of the river soon dwindled away. The RiverLine now provides a pleasant one-hour excursion along the riverbank, down the main streets of some cute little towns, past some remarkable woods and wilderness up near Trenton, and past Camden's urban revival at the other end.

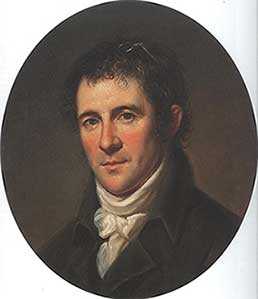

Stephen Girard 1750-1831

|

| Stephen Girard |

Girard was born in Bordeaux, France and never went to school. By the age of 23, he had become a sea captain, like his father and grandfather. By the age of 27, he owned his own ship and was thus launched on a successful career in a very dangerous occupation. Depending on the destination and weather during that era, up to forty percent of sailors were lost at sea on long voyages. From the point of view of the passengers and shippers, when you were selecting a captain you wanted one who had returned unharmed from many voyages. It was irrelevant whether he had been lucky, or diligent, or had learned a lot from his relatives in the trade.

Stephen Girard did start with a handicap, being born blind in one eye. It may have been a personality disorder which drove him to precise, minute instructions to his subordinates in excruciating detail; he might now be called a "control freak" and be disliked for it. For example, he kept a handwritten copy of all letters he wrote, and at his death, there were 14,000 of them, sorted and filed. His wife went insane, and after spending years at the Pennsylvania Hospital, was buried on the grounds. If this is the price of being rich, some might consider remaining poor. During his working years in Philadelphia, he would normally get to the counting-house at 5 AM, go to his bank at noon, and go to work on his 600-acre farm in South Philadelphia after 5 PM. He said he liked farm work the best. The image left behind by this role model, then, was workaholic. Nevertheless, if you wanted to become the richest man in America, here was the pattern to follow.

Girard probably came as close as any rich man in history, to "taking it with him" when he died. His innately compulsive personality, combined with the sure knowledge that his relatives and others would probably try to break his will for their own benefit, led to the construction of a last will and testament that withstood a century of court challenges. It launched remarkable philanthropy for thousands of orphans and organized the whole Delaware Valley into an industrial machine unlike anything else in the country. Although he left the largest estate in the nation's history, that estate continued to accumulate money from his minute instructions to executors, eventually enlarging his vast fortune fifty-fold, a century after his death. In retrospect, Philadelphia might well have slowly declined into obscurity after the nation's capital moved to Washington in 1800. Instead, the coal, canal, railroad and industrial empire of the Philadelphia region became the "arsenal of the North" during the Civil War, and the main wealth generator of the Gilded Age which followed.

Girard's business career can be somewhat oversimplified as consisting of shipping at the base of his early good fortune, followed by banking during the era when banking was poorly understood and usually ineptly managed. He ended his career with an eager and successful embrace of the emerging Industrial Revolution. Throughout all of this, he characteristically took great risks for great profits, through recognizing what others were too timid to accept fully. On many occasions, his risky ventures resulted in very large losses, made acceptable by other risky ventures proving unexpectedly successful. An example would be Girard's Bank. When the Federal Government first started and then abandoned the First National Bank Girard bought up the remnants and made a great private success of banking, where he had little previous experience. He saw the potential of the canals, and later the railroads when others were content to be farmers or country gentlemen. When he was 79 years old, he purchased vast tracts of wilderness containing some outcroppings of coal, because he could foresee a great industrial future for the region. No pain, no gain.

Another way of looking at Girard was as the most prominent French-American citizen of his time. He arrived in Philadelphia at about the same time Benjamin Franklin stepped off another boat, returning from abusive treatment by British officials which finally flipped him for American independence. Franklin recognized that independence from England meant an alliance with France, or else it meant defeat. It is possible to view the American Revolution as an episode of France searching for an American foothold after its expulsion fifteen years earlier in the French and Indian War; trouble between Britain and its colonies might re-open opportunities for France. Girard was extremely friendly with Thomas Jefferson, the most Francophile of founders and early American presidents. When the War of 1812 with Great Britain threatened disaster for the new American state, Girard staked $8 million dollars, his whole fortune, on financing that war. During the entire period from 1776 to the Louisiana Purchase, America was wavering between its gratitude to France and underlying loyalty to the English-speaking community. During that long formative period, Girard the very rich Frenchman was hovering in the background, probably influencing American foreign policy more than is known, even today. But the France that Girard stood for was neither aristocratic of the LaFayette variety nor intellectual of the Robespierre sort. It was France of the French peasant, crabbed, acquisitive, and morose, forever responding to a "hidden hand" of his own self-interest in a way that paradoxically benefited his whole community, and thus would have hugely amused the Scotsman Adam Smith.

The Houses in the Park

|

| Strawberry Mansion |

Fairmount Park is said to be the largest park (7000+ acres) within the limits of an American city, and in fact, maybe just a little bigger than the city can afford to maintain. It was established in the middle of the 19th Century through the efforts of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to reverse the Industrial Revolution's relentless pollution of Philadelphia's Schuylkill River and the water works. The waterworks were built in 1801 in the mistaken belief that Yellow Fever was caused by pollution; Fairmount Park more accurately responded to the idea that Typhoid Fever was waterborne from upstream pollution. Lemon Hill, the nearby mount containing Robert Morris' Mansion, was purchased to expand the reservoir capacity of the waterworks and thereby made the Art Museum possible where the reservoirs were originally located.

The Park has long constituted a symbolic interval between center city and the suburbs. Since the construction of the river drives and later the expressway, the commute along the river amidst trees and parkland has made an entrance to town a pleasant experience. If the town planners had been able to foresee automobile commuting, they might have anticipated that the sun would be in the driver's eyes coming East during morning rush hour, and in his eyes as he went home toward the West in the evening. Driving safety might perhaps have been impaired by the tendency of this glare to direct attention to the park rather than straight ahead, but nevertheless redoubles the effect of the park views as a daily aesthetic experience. Even the pollution idea had its ambiguous side since animals increase the bacterial runoff from their grazing areas, and the original houses in the park had many pastures. Strip mining, however, allows mineral contaminants to be washed by rain into the watershed. The city waterworks today extract nearly 800 tons of sludge from the water supply, daily. Whatever the effect downstream, the high ground had less malaria and less typhoid than swampy lowlands, so many of the original houses were useful summer retreats for city dwellers during the early years of the city.

The park is governed by the Park Commission, and at one time had its own police force, the fourth largest police force in the state. Started in 1868, the Park Guards changed their name to the Park Police and then became part of the Philadelphia Police in 1972. The original 28 officers had grown to 525, had their own police academy and a proud tradition. It seems very likely that some deep and dirty politics were played in this shift of authority, and it might be a fair guess that some bitterness still survives in the circles who know and care about these things. In 2008 a scarcely-noticed rule change gave the Park to the City Department of Recreation, thus placing it just a little closer to ambitious real estate development. Our present concern, however, is with the houses in the park.

There are seven of them, kept up and maintained by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Guided tours are provided intermittently by the museum, but since funds are limited only three of the houses are open year round. The others are equally worth a visit but unfortunately, are closed during the height of the spring flowering season. Two of the year-round houses represent the two extremes of Philadelphia culture, since Mount Pleasant was owned by a buccaneer ("privateer") named McPherson who lived at the height of 18th Century elegance, while Cedar Grove was originally a Quaker farmhouse of the greatest simplicity consistent with honest comfort, a style which persisted relatively unchanged until late in the 19th Century. Benedict Arnold and Peggy Shippen looked at Mount Pleasant with an eye to purchase but never lived there because they were called away by national events. With the addition of modern plumbing and air conditioning, Mount Pleasant would be an elegant place to live, even today. McPherson had to sell the place to pay his debts, whereas the Wister and Morris descendants of Cedar Grove still populate the Social Register in large numbers. The two houses completely typify the underlying philosophies of the two leading Philadelphia classes of leadership. One group measures itself by how much it spends, the other group measures success by how much it has left.

REFERENCES

| Treacherous Beauty: Peggy Shippen, the Woman behind Benedict Arnold's Plot to Betray America: Mark Jacob:978-0762773886 | Amazon |

The Walking Purchase

|

| William Penn and the Indians |

Any fair discussion of Quaker relations with the Indians must emphasize that almost all other colonists of the time regarded Indians as subhuman components of the local wilderness. Only William Penn was careful to treat the Indians as fellow human beings, entitled to fair play, dignity, and respect. Like a good politician, he entered into their games with enthusiasm and definitely earned their respect by outdoing them all in the broad jump contests. Even though he had bought the land from King Charles II, he took care to buy it a second time from the Indians, and for many decades was able to enforce the wise rule of never permitting settlers on the land before the Indians agreed to its purchase. After Penn's death, however, and particularly from 1726 to 1736, a major wave of German and Scotch-Irish immigration created an overwhelming population pressure on the seaboard areas, resulting in much unauthorized pioneering and settlement. Since William Penn spent only a few years in the colonies his agents chiefly James Logan, had long set the tone.

|

| Walking Purchase |

Logan had been equally famous for his many efforts to treat the Indians fairly, and the grounds of Stenton, his manor house, were often filled with Indians come to pay their respects. Against all this evidence of the benign attitudes of both Penn and Logan, there stands the episode of the Walking Purchase of 1737. No doubt about it, the Indians were treated badly.

In the triangle between the Neshaminy Creek and the Delaware River, the Delaware Indians agreed to a sale with the third side of the triangle established at a distance from Wrightstown, as far as a man could walk northward toward the Wind Gap in a day and a half. That was a common form of boundary for Indian land sales, and its distance was fairly well understood. In anticipation of pacing out the distance, the colonists sent out explorers to find the easiest path, then sent out woodsmen to clear a path in the forest, and selected three of the fastest runners in the colony to do the running. The pace was so fast that two of the runners had to drop out, and the third one nearly did so. The resulting boundary was nearly twice as far into the wilderness as was commonly accepted for the measurement, taking advantage of the sharp bend in the river which widened the land in question by a great deal. The Indians were so disgusted they refused to leave the territory. Logan had already made an agreement with the Iroquois nation, to whom the Delawares were subject, and the Delawares only surrendered the land when the Iroquois began to look as though they really would act as enforcers for the bargain. Although serious Indian warfare did not break out for another twenty years, the Walking Purchase went a long way toward convincing the Delaware tribe that the Quakers were no more trustworthy than the settlers in other colonies, and is said to have been on their minds when twenty years later they helped the French decimate General Braddock's army.

There will probably never be a clear resolution of the paradox of Quakers, particularly Logan, behaving in this reprehensible manner within a very long history of the unusually honorable treatment of the Indians. With William Penn now dead and gone, no doubt Logan was caught in a squeeze between the two rather dissolute sons of William Penn, neither of them Quaker, who had over-indebted themselves with high living and were pressing their agent to make land sales to pay for it. Then there was the pressure of the new German and Scotch-Irish immigrants, brought to the New World by real estate promises, and stranded in the seaport unable to complete their land purchases. Under this pressure, Logan may have been unduly persuaded that the 1684 treaties with the Indians, along with many other treaties and understandings, were all the legal justification he needed. Whatever the specifics of the situation at the time, it is now clear the Walking Purchase was a blot on the Quaker record that can never be entirely justified within the Quakers' own standards of fairness. Within the Society of Friends, whatever other English colonists might have done in their position, let alone what French and Spanish regularly did to the Indians, doesn't matter in the slightest.

Ownership of the Port

|

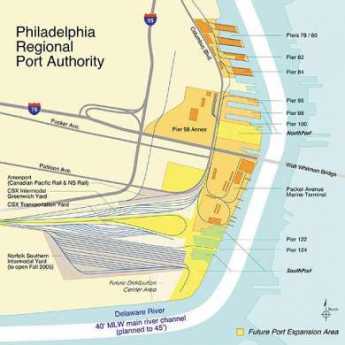

| Delaware Port |

One of my children studied for a graduate degree in Economics, and once remarked there only seemed to be one thing worth learning, namely Comparative Advantage. How's that, again, child? Free trade is good, dummy. By inference, tariffs and subsidies of local industries are a bad thing. All this talk about losing jobs to China is misguided, holds back world prosperity. If that's the case, Child, then why is the Philadelphia port run the way it is? Because Philadelphia is in a life struggle with other ports, and they all run the same way.

There are 23,000 people working in and around Philadelphia port, almost all of them paid wages that are a little surprising to hear. If you include such things as worker's compensation, the wage cost of a Philadelphia longshoreman is about fifty dollars an hour. With such a wage cost, the port cannot compete with other ports, particularly when you see how easily a shipping line can unload the ship elsewhere, with lower wage costs. The consequence is that no private company can afford to own and operate a marine cargo terminal. In our case, they are owned by the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, which is indirectly to say they are owned by the State of Pennsylvania. The regional port authority has a $300 million annual budget, owns eight terminals, loses money, and is taxpayer subsidized. If you skip all the intermediate steps, the taxpayers of the state subsidize the port workers. In return, the rest of the state gets its Cocoa and steel shipped. What Philadelphia gets is union domination of its politics.

|

| Ship Yard |

It's easy to be too glib about all this. Billions of dollars have been invested in the transportation infrastructure and distribution organization, organized around this particular structure. Furthermore, many billions more have been invested in the industries which are based on the assumption that this distribution system will serve them. Philadelphia has the port, but a vast region depends on it and will react swiftly if changes are made too precipitously. There really does seem to be a need for the Foundations and Universities to support some useful studies about what direction the region ought to take, however slowly we move to get there. At the least, we could give some serious thought to the wisdom of going further in the direction we are going.

Finger Piers are a thing of the past and must be replaced by container cargo terminals, we are now told. Should we really spend the billions of dollars it would take to make this change? It would obviously be unprofitable for some private corporation to undertake this effort, so what can we do to make it profitable?

The natural depth of the river channel is 17 feet and needs to be dredged to 40 feet to accommodate the container ships, which we're told carry more profitable cargo than bulk carriers. We are also told this is being blocked by the New Jersey government, responding to competitive pressure from Northern New Jersey interests who want the cargo to go to Hudson River terminals. Presumably, this is a sign that New Jersey and New York are subsidizing their ports, too, and we are in a bidding war.

Thank goodness for the Constitution, which discourages shooting wars between the states.

River City

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dock Street

Founding Fish

In 2002, John McPhee brought out a perfectly splendid book about fish and fishing history in this region, with particular emphasis on shad. He makes the whole topic remarkably interesting, but you have to be a little wistful about the way he demolished a splendid story of fish in Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War. The book is called The Founding Fish. As everyone knows, George Washington and the Continental Army were starving and freezing at Valley Forge, a few miles up the Schuylkill, while Major Andre and the other British officers were cavorting downtown with the Tory ladies, grr. The story has long been told that things got to a desperate state at Valley Forge when, lo, the annual shad run was several weeks early and mountains of fish came roaring up the river to the excited shouts of the starving patriots and rescued the raggedy starving Continental Army. It would make a wonderful scene in a movie. McPhee tells us that George Washington was in fact a shady merchant, having caught and pickled many barrels of shad coming up the Potomac River. The annual shad excitement was no news to him, and it seems quite possible he selected the campsite at Valley Forge with this spring event in mind. Shad was no news to the British, either; there are records of their trying to block off the Schuylkill with nets to prevent the fish from getting upriver to Valley Forge. Unfortunately, a careful search of letters and records fails to record any shad run earlier than April that year. The rescue of song and story does not appear in contemporary documents. What's more, some unnecessarily diligent scholars have sifted through the garbage heaps of the encampment area, and have only found pig and sheep bones, no shad bones. Those graduate students undoubtedly deserve to be awarded degrees for their work, especially the digging in garbage part. But nevertheless, it all does seem a pity to ruin a good story that way. Fair Mount

Although the Art Museum now dominates the end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the earlier focus of the acropolis once called Fair Mount is just down the hill behind it, in the old Grecian complex of the Philadelphia waterworks. When the Schuylkill was dammed at that point, the effect was to calm the rapids, drown the falls at Midvale Avenue upstream, and turn this portion of the river into a placid fresh-water lake. Fairmont Park was then created upstream in an effort (originally stimulated by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia) to reduce pollution of Philadelphia's water supply going into the pumps at the Waterworks, by replacing, with parkland, the wards, and industrial slums at the terminus of the canal bringing anthracite from upstate. The result was the creation of an ideal place for public boating and skating. The transformation of this area can be seen in retrospect as an impressive civic response to economic upheaval. The War of 1812 (by cutting off ocean access to bituminous via the Chesapeake) had first forced Philadelphia to use anthracite hard coal, and the discovery of anthracite's superiority in making steel caused a continuing reliance on it and the canals

that brought it here. By 1850, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad made the canals obsolete and created this splendid opportunity for urban renewal. The waterfalls had created a natural boundary between industry oriented to upstate coal and other industry oriented to oil and commerce coming up Delaware. It is a great pity that the lower section of the Schuylkill, once so famously beautiful, has never stimulated the same vision and imagination in response to the eventual decline of the industrialization which defaced it. To return to Boathouse Row, a large azalea garden starts the Park, and then the East River Driver winds along the attractively landscaped riverbank. Just beyond the azalea garden, the first of ten Victorian-style boathouses starts the home of the Schuylkill Navy, an association of rowing clubs which are now a century and a half in residence there. When the Schuylkill auto expressway was created on the other side of the river, someone had the bright idea of decorating the rowing houses with lights along their edges in the manner used for Christmas decorations in South Philadelphia, especially on Smedley and Colorado Streets. Ever since the entrance to Philadelphia from the West has become one of its most arresting beauties.

Add a few cherry blossom trees in the spring, and you have quite a memorable centerpiece. Rowing sometimes called crewing, or sculling, is a central focus of Philadelphia society, and is curiously not something in which the city can claim to be first or the oldest. As you might expect, "regatta" is a word invented in Venice five hundred years ago, there are records of rowing races as far back as 400 BC, and New York -- ye Gods! -- had the first American boating club. The Philadelphia Schuylkill Navy was formed as an association of rowing clubs in 1858, and the oldest member, the Bachelor's Barge, was only formed in 1856. The development was largely spontaneous and is said to have been briskly stimulated by a beer garden nearby, run by a former Philadelphia sheriff. About the same time, the British became crazy about the sport, having the Henley Races as the most famous regatta in the world, and both the Australians and the Bostonians occasionally have the largest, most expensive, most widely advertised regattas. Foo. Philadelphia has the Schuylkill Navy, and it is central to our existence. There are a couple of things which are unique about rowing. In the first place, it is hard to think of a way to cheat. You can hire engineers to redesign the shape and size of your boat, but engineering really doesn't make a lot of difference once the basic development of oarlocks and movable seats was perfected. A good boat can cost as much as $30,000, but that is large because all boats approach the limit of speed. If you have heavier or stronger oarsmen, it doesn't make that much difference. What matters is coordination, and in the longer boats, teamwork. Pull up with your shoulders, push with your legs, don't start with your buttocks, the art of rowing involves your whole body. The greatest champion of all time, Edward "Ned" Hanlan,

only weighed 155 pounds. Not only was he world champion from 1876 to 1884, he was undefeated in any race during the last four years. True, he was born in Toronto, and eventually he was thrown out of polite Philadelphia racing for deliberately ramming another boat, but those are private Philadelphia comments, not something you want to talk too much about. The whole secret of rowing is to manage the fact that the boat travels farther between strokes than while the oars are in the water; if you row too fast, you actually slow the boat. There are two other Philadelphia names associated with the Schuylkill Navy. One is Thomas Eakins, the great American painter, one of whose most famous pictures is that of Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (on the Schuylkill). The other name is Kelly. John B. Kelly of Philadelphia won two Olympic gold medals in 1920 and did it within one hour. He won a Third Olympic gold medal in 1924. But when he tried to race in the Henley Regatta, he was declared ineligible to row, because he had worked with his hands (summer work as a bricklayer), and thus could not really be called a gentleman. Anyone who has ever heard Irishmen talk about Englishmen can imagine the reaction this caused in the Kelly family. The resentment took the form of pushing his son, Jack, into racing, and in 1947 John B. Kelly, Jr. won the Diamond Sculls at Henley. Meanwhile, the father vindicated himself in other ways. The firm of Kelly for Brickwork was an enormous financial success, right up there next to Matthew H. McCloskey and John McShain, the political builders of the Pentagon and numerous other government buildings. John B. Kelly unsuccessfully ran for Mayor of Philadelphia in 1935 during the 75-year period when Philadelphia Mayors were always Republicans, but for decades was in the much more powerful position of head of the local Democratic party. The Republicans at that time would meet for lunch at the Union League, and so John Kelly reserved a lunch table at the Bellevue Hotel, next door, where he could be seen holding court every day.