0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

A New Currency? Equity Savings Accounts.

FRONT STUFF::A New Currency? Equity Savings Accounts.

Overview

At first, currency and healthcare appear to be unrelated. However, after composing four books about Health Savings Accounts, currency-backing and health-financing now seem to have much more in common. In particular, interconnections and ideas appear along the way, and new ideas emerge as extensions of the original one. This slender volume uses that quality of composition to explore what it might be like if three concepts (backing the national currency, preventing currency manipulation, and total-market index funds) were combined.The basic idea turned out to have considerable coherence, with index funds well suited as universal "standards of exchange" (instantaneous indicators of market value). That was especially valuable when the trade becomes injured by out-of-control inflation. Index funds, however, are less satisfactory as long-term "stores of value", when nations resort to currency price manipulation, which they can use to resist the afore-mentioned commodity price stabilization. Therefore, a common standard is required at two levels, not just one. In the Bretton Woods system, the supra-national level is the Special Drawing Rights of the International Monetary Fund.

It is here suggested stock index funds be the price standard which substitutes for both currencies and SDRs, thus removing both levels from political control, but in different ways. In all this, they somewhat resemble Health Savings Accounts, where the price of healthcare could be stabilized by market-basing its finance on passive (i.e. total stock index) investing, a concept which was never envisioned at their beginning.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Health Savings Accounts were created in 1981 by John McClaughry of Vermont and me when John was Senior Policy Advisor in the Reagan White House. The underlying idea was patterned on the tax-exempt IRA (Individual Retirement Account) devised by the late Senator Bill Roth of Delaware. Its three revenue-enhancers were the tax exemption, compound interest magnification, and the incentive to save for yourself rather than for demographic groups of strangers. Almost any financial institution might handle the straightforward mechanics, with policy decisions shifted toward the customer who owned them. Fitting for a medical emphasis, HSA tax-exemption was confined to medical expenses, with unexpected big medical events covered by inexpensive high-deductible health insurance. But switching from favoring health issues to favoring more trade and more economic growth was less a revenue issue, and more a hindrance-removal one. So when the focus changed to international balances, it then needed international features to channel it, while purely medical features could be downplayed. The thing they had in common was a large and dependable funding pool. The effective size was not how much was deposited into them, but how much could be withdrawn when it was really needed. Only later was it realized that a substantial amount might be left over at age 65, where it could be used to fund the extended retirement of those with superior health. Not only did that extend the period of compound interest, but it also provided an incentive for younger people to save even though they felt no threat of illness. The emphasis shifted somewhat from the threat of sickness expense to that of a lifetime reserve fund.

The idea of a nation state, on the other hand, was established for the Western World in 1648 by the Treaty of Westphalia, after the Thirty Years War over Religion. It took years of squabble and deep thinking to arrive at a simple formula allowing for multiple religions in Western Europe: a nation was to be inflexibly defined by its boundaries, and within those boundaries, the nation's religion was defined by the religion of the King they happened to have chosen by their own methods. Everything else could move across borders. The nature of the currency posed a slightly different problem from religion. Kings were regularly observed to cheat on the currency, mostly to finance wars about boundaries. National sovereignty was both enhanced and subordinated to accommodate religious problems. Everything else was negotiated between kings, mostly by fighting wars as it turned out. Three hundred years later, religion was of reduced importance, kings were nearly irrelevant, but the issue of an international currency continued to fragment European harmony.

The quantity of gold within a nation roughly matched its economic prosperity, and ways had been devised to inhibit it from migrating while the trade it symbolized was encouraged to move around. The King controlled paper money (or any other surrogates for gold serving as public-owned instruments of trade), within and between nations. Meanwhile, the quantity of gold remained fixed and "owned by the King" until some form of "squaring up" took place. There were two disadvantages: prices were suppressed by the fixed value of gold, as before. But periodically new gold was discovered in the ground or conquered in wars in a haphazard (non-trade, non-economic) way. In particular, two Twentieth century world wars disrupted the roughly fixed relationship between the King's possession of gold and the public's economic health. The United States eventually found itself with practically all the world's gold in 1945, so nobody else could buy anything from us. That was carrying theory to the point of paralysis.

The Bretton Woods Conference did supposedly devise a patchwork substitute, but the seeds were sown for eliminating the gold standard. In its place was put a system of national central banks, trading through the International Monetary Fund, which used a super currency called International Trading Receipts to square up national accounts. Freed of the gold restraint, there might emerge a gradually enlarging currency pool as the populations grew and supposedly shrink during international recessions. This arrangement supposedly solved the inflexibility of gold. However, without a metallic currency standard, nations found various ways to cheat, just as kings had historically found ways to cheat on gold. Inflation resulted, the power of treaties was always less than the political power of the state, the independence of central banks was eroded, and small, steady but relentless inflation resulted. That brings us to the present: we have no gold standard, but the various world economies are periodically on the edge of war about international trade. Inflation seems less threatening than war, so the balance between inflation and war calls the tune in the monetary trade dance hall. The public does not understand, but is restless about the future, as it well might be. At the moment, a huge proportion of the world in the third world have become economic factors, while retaining pre-1648 tribal patterns rather than becoming nations of boundaries. "Floating" currencies address this problem, somewhat at the expense of dependable trade relationships, and possibly the third world.

We now propose to interpose the Health Savings Account concept into this precarious arrangement. To do so, we minimize medical features and expand currency ones. Background features like index investing and individual ownership become vitally prominent, while health yields importance to demographics. But the ideas of tax exemption and equity investing are expanded to meet the changed focus on trade. Eventually, the evolution from a Health Savings Account to a monetary standard becomes obscured. But it is substantially based on the same approach. There are two alternative approaches available. Either substitute the index funds backing HSAs for metallic monetary standard or else substitute the same sort of paper for the International Trading Receipts now used for trading between nations at the International Monetary Fund. One would replace the Federal Reserve's system of adjusting the paper value of a nation's currency, relative to its nation's economy. That would center the nation's money supply on the size and health of its economy, and work better as a medium of exchange.

The other would substitute the same paper for the International Monetary Fund's (IMF's) Special Drawing Rights, hoping to regulate the long-term store of value function by having long-term money come closer to representing real underlying values, as assessed by its trading partners. Both such changes would involve a change of power, and so would be opposed by successfully constructed power centers. Even in a crisis, these centers would attempt to maintain their control. So they must be described as anticipating a crisis, possibly one which might never occur. They would serve notice on both incumbent power centers that alternatives have been prepared in case they fail, and perhaps improve their performance to prevent failure.

Currencies Decided By Committee, or Self-Balancing?

Volume of cases easily overwhelms American courts. It is illustrative to see how they protect themselves, at least as an example of how any deliberative process isolates itself whenever the volume of emergencies swamps its ability to respond. Civil cases between contestants differ somewhat from criminal cases between the state and a criminal, but both similarly slow down rate-limiting processes in order to keep themselves functional. Numerous steps are imposed to slow even a hearing of grievance in court. The key to the multi-step approach is to demand sequential due process instead of allowing numerous steps to proceed simultaneously. The costliness of attorneys transforms a convoluted process into an expensive one, so long delays at each step are part of the discouragement dance. It costs the state money to hold trials in marble palaces, so protection of the defendant can also be viewed as attempts to convert trials into settlements, thereby reducing the caseload of the court. By contrast, the voluminous transactions of trade demand iron-clad guarantees of payment, instantaneously. A million dollars can change hands as a result of a few words over the telephone. Your word is your bond, and God helps you if you default on it. Computerized transactions have eased this contrast somewhat, but the fact remains that slowness cripples trading, and essentially no excuses are tolerated. Business hates rules, hates procedures, hates anything which threatens delay, and therefore recoils at anything which might get a committee involved.

This commonplace is such a vital point it deserves elaboration. When a buyer and a seller meet to conduct business, the buyer prefers the goods to the money, while the seller would rather have the money than the goods. Both come away feeling better after the transaction, so the more transactions handled, the more profitable each will be. The impatience of the businessman deserves respect. Therefore, automatic rebalancing is greatly preferred to haggling. Automatic rapid rebalance is almost invariably more profitable than decision-making by a committee. Ultimately, automatic monetary standards will be greeted warmly by traders. The technical problem is to find a non-consumable but valuable monetary standard which unlike gold has a non-capricious volume, and unlike a formula, requires no tedious calculation. You can make any system a little better, but if it only has these two characteristics, it's likely to be as good as it will get.

Accordingly, it is here suggested we have a look at creating an index fund of the common stock of all the currencies of participating nations and use it as a monetary standard until it seems safe to eliminate nations as middle-men entirely. It would represent a gain of real value in the world, fluctuating automatically with smaller changes of opinion in the economic world, and unconsumed by using it. Everyone in the world would be able to follow its movements by big-data computers, minute by minute. Its use would undoubtedly be good for trade, although its effect on political thinking might only emerge from experiment.

The political point was long ago established by the experience of gold-carrying Spanish galleons. If a ship sank in a storm, the gold was gone. So massive international trade only began to flourish when gold certificates were substituted for the real thing, probably by Robert Morris. If the paper certificate got lost, the gold was still in the vault and new certificates could be issued. This important advantage of paper money over articles of intrinsic value must be acknowledged and minimized. It lessens the accidental risk, but it impairs the ability of debtors to conceal a weakened fiscal condition. In situations where paper money is mainly supported by military power, it could be argued that increased transparency encourages military threats. Consequently, it is deflationary to the degree that nations (ultimately, individuals) would default on their debts, and some third party might have to hold the certificates in order to guarantee them. The third party would expect to be paid for the service. Negotiation and technology might solve the problems, but there would be problems, both real and imagined.

Currencies Owned by Nations, or by People?

|

| King Midas |

Let's remember why this subject came up -- we essentially don't have a monetary standard, gold or anything else, although it seems likely a suitable monetary standard would lead to a better state of economic affairs. King Midas is thought to have invented the metallic-standard idea, and whether that is true or not, national currencies backed by gold are thousands of years old. No doubt, the Spanish galleon idea was a new slogan for an old idea which goes back at least as far as paper money. Consequently, people carried the gold coins around in purses, but still trusted the King to accumulate the gold and mint it into coins for them.

|

| Gold Coins |

History shows that kings regularly abused this intermediary role, by shaving the coins and other forms of short-weighting them. Meanwhile, kings felt they needed to accumulate funds for wars and other national purposes, and controlling the currency was a needed revenue generator. But the land was also used for aggressive national purposes, rewarding local chieftains for their loyalty, and substituting for the loan of mercenaries or other war materials. But when you give away land, you give away part of your kingdom, always a risky business. The more you think about history, the more convincing is the argument for gold, from the point of view of the king, if he is the middle-man. The argument for the individual citizen to surrender his gold to the King to parcel out to the citizens a second time is a little less dispositive. People have always grumbled about taxes and demanded more than protection in return for paying them. But pacifists have always resisted taxes disproportionately, arguing if we could become more peaceful, we might need fewer taxes. In a modern context, it is hard to imagine individual citizens making atom bombs, aircraft carriers and other means of winning wars. Less convincingly, the idea of a government using taxes to create state capitalism has been a second-best argument for governments to expropriate individual wealth. If it works at all, it has not proved itself in two hundred years of trying. Nevertheless, this line of thinking probably enlists significant leftist opposition to individual possession of physical wealth.

|

| Industrial Revolution |

Although the idea has provoked angry discussion for centuries, it is likely the opposition of leftists and the uneasiness of rightists would at best limit support to winning the agreement of a bare majority of the rest, probably only under convulsive circumstances, and probably only to a partial degree. The prospect of individual wealth possession, without forcible physical defeat, must content itself with sharing possession of the monetary standard with the government, until a partial test of the idea shows it has such economic advantages to trade and to peace, that further resistance is futile. The concept may possess such power, but it must overcome what is at present an unconvinceable opposition, and rest its case on unexpected success with creeping implementation.

The closest historical test would be the international experience with Spanish pieces of eight during the age of piracy. We do not have adequate history to use this period as a dispositive example, but it is certainly true that government was weak on the high seas And that national currencies regained dominance afterward when governments got stronger. It is also true the age of piracy was followed by the Industrial Revolution, or the Age of Enlightenment, or the French Revolution. A case could be made that any one of these consequences had roots in the Age of Piracy, but not a sufficiently powerful one to end debate. Here again, we must carry analysis as far as we can, but only expect to settle the question after experimentation with it. So, let's describe it more fully, to see where that gets us.

Equities, Not Debt

|

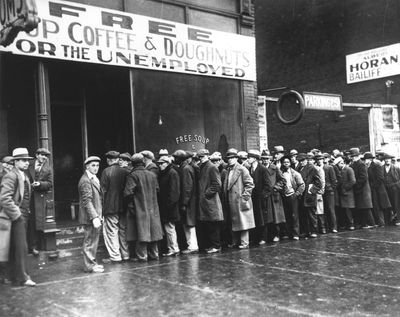

| Great Depression |

I confess to this feeling in myself: stocks are riskier than bonds. So I don't blame a lot of other people for having the notion left over from the Great Depression of the 1930s that stocks can suddenly drop, whereas bonds are rock-solid investments. That is an obsolete viewpoint which I know is obsolete, but I still have it. Governments have learned that issuing more bonds dilutes the ownership shares, effectively making the sovereignty risk the same, for both. But what makes this work is to go steadily deeper into debt. We established the rate at 2% a year, but wars and other catastrophes make it more than that. When we reach our limit, leadership changes, but we don't stop adding debt. We don't like to see that, so we skirt around it. Something will turn up.

|

| Robert Morris |

So let's look at history. When Robert Morris was running America's affairs during the Revolutionary War, he formed the opinion that governments should borrow all their revenue, while businesses might sell ownership shares to raise money. Corporations were just getting started in this era, but Morris extended this idea to the modern era when he was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1789. Apparently, he did a lot of talking in private, but this concept is tightly identified with him, allowing it to appear to be almost his sole contribution to the subsequent capitalist republic. It was a two-step method for individual citizens to control the behavior of a strong central government. During the early decades of the Republic, the banking system emerged, and it evolved that big corporation sold bonds in bulk to create indebtedness, while individuals and small businesses usually borrowed smaller amounts from banks. When the economy collapsed after 1929, the impression was reinforced that bonds were strong, stocks were unsafe, and bank deposits were especially unsafe. That's not necessarily the case.

|

| U.S Mint |

The process of gradually going off the gold standard created slow steady inflation of the currency, so a dollar in 1913 was worth a penny, a century later. Indeed, it now costs the U.S. Mint two cents to produce a penny. The slowness of this attrition allowed a trade to function during the century, and stocks accordingly rose, but the fixed value of bonds made them relatively unsafe over longer periods of time. After a brief, disastrous, flirtation with negative interest rates, bond prices limited their declines to the "zero bound", and sensible people avoided bonds as an investment. Speculators might make big profits from minor fluctuations, since doubling fractions of one percent could be leveraged to big speculative profits, up and down. But these profits were of the "zero-sum" variety, meaning all profits were at the expense of your counterparty's loss. Stocks, on the other hand, could make profits on a "win-win" basis. True, they could also lose on a "lose-lose" basis if inflation got out of control, but at least there was some chance of financial survival. Generally speaking, however, the position of stocks and bonds had been reversed, and bonds were riskier. Governments don't like to have that acknowledged since the Morris system confined all of their revenue to bonds. No one would freely buy government bonds if everyone believed this analysis. Except weakened governments, ultimately limited by the "zero bound".

|

| Stock Market |

No strong case is improved by exaggeration. There is still plenty of risk in the stock market. The aggregate value of stocks can go up and down, as a reflection of the ups and downs of the whole economy. But it is true that corporations increasingly form the bulk of the national economy, represented by their shares on the open market. Governments are usually restricted to borrowing for revenue and, reaching the limit of their borrowing power, they are impelled to expand the scope of government spending. A resort to socialist systems is usually a sign of desperation soon to be disappointed, although socialism might possibly work when you don't need it. When you hear socialism praised, it is questionable if even reserves will save you because socialism (government control of production) wastes reserves even faster.

REFERENCES

| Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution | Amazon |

Passive Investing With Total-Market Index Funds

What we once called investing in the stock market, is now increasingly called "active investing" because of one man, John Bogle. Mr. Bogle, a main-line Philadelphian, invented index investing (now renamed "passive" investing) as a competitor to "stock-picking", now to be called "active" investing. It's made possible by high-speed computers. What hasn't been much commented upon, is that Fidelity, nominally a Boston firm which is second in size, is actually controlled through a Philadelphian named Solmssen, through a web of holding companies.

The original index investing used the Standard and Poor 500 list, providing high-quality diversification, adjusted for size. It was probably selected because it had a good record of smoothing out three common variables in a stock portfolio. Other lists had good records, too, but generally, the stock-pickers for the list were famous and therefore well-paid, hired by successful companies which took another cut for selecting such good stock-pickers and advertising their success. This arrangement selected stocks which performed well, but it added cost. When computers made it possible to construct an index of the entire stock market of a nation or even the whole world, it emerged that such inclusive lists performed as well or even better than active stock-picking, net of transaction costs. Because the index changed slowly, transaction costs were fewer, and consequently, fixed taxes were lower, because less frequent. Indices were then tested for different nations, different industries, different sizes, or any other sort of difference. While many claims have been made for particular semi-active indices, they all increase internal trading volumes, so their costs also go up, although slowly. At the moment, it is generally felt that results are very similar; it is certainly true that trillions and trillions of dollars are shifting from active investing to passive index-investing. Nation-wide, or even world-wide, indices are thought to be essentially investments in the economies of the whole geographic area. The ultimate simplicity would be to buy the certificate, put it in a bank lock-box, and forget it for a lifetime. So far, this is essentially how things have worked out.

In spite of the stampede-like character of recent trading, there is still a majority of stock in individual accounts. Most of this stock has accumulated taxable gains which would diminish in net value if sold, and simple inertia is also not to be under-estimated. If all such stock were converted to passive accounts, no one can say if the net result would raise or lower the final value of index holdings. Nor can one be sure the unsold hold-outs would be largely limited to insiders who have personal agendas rather than economic ones, eventually leading to unfortunate gyrations of the aggregate price which would lessen ties to a true value. Nor can anyone say whether the habit of buy-and-hold will become so ingrained that people will hold on when they should be selling. All that might be said is that, so far, none of this has made an appearance. And meanwhile the sands of time are running out, the train is leaving the station. At present, the most likely prediction is that overall volatility will be reduced, but true value can be assessed by the P/E ratio, the ratio of price to earnings. And a lot of brokers will have diminished income.

At the rate things are going, answers to this sort of question will seem stable in about five years. Beyond that time, waiting for more answers will probably mean waiting forever. So let's ask the simple question again. Why not use some sort of a total stock index as a replacement for gold in the return to a gold standard? Forget about going beyond national control toward individual citizen control, because that answer is already predictable: traders will like it, governments won't. But governments are sometimes nearly immortal, and people aren't.

Achieving Meaningful Volume Quickly But Tentatively

To explain the (index-fund) connection between gold standards, and Health Savings Accounts, a passive investment can support entirely unrelated payment requirements. Index funds held in escrow would be tangible stores of value for unspecified future expenditures, earning substantial income from otherwise idle money, but taking up little storage space. At the other extreme, their collective prices might merely provide non-subjective price discovery to replace the subjectivity of central bankers on the honor system. Obviously, market-based prices are subject to occasional panics but might serve for short-term experiments. A mixture of the two, some in escrow, some immediately salable, might serve both price discovery and as stores of value.-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Medical expenditures are commonly stated to be nearly 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP). That's a lot of idle money, which if capitalized might give a meaningful boost to the national, or even total world economy, by expanding borrowing capacity. The experience with gold was you didn't need to match the entire money supply. Less than 20% provides adequate price discovery, even employing a useless metal like gold. Since passive investing is a by-product of computers, there has been too little experience to predict exactly where so much extra capital would take us, but there is every reason to foresee generally favorable results. Unfortunately, there is also every reason to fear some unexpected harm might pop up somewhere, to make us wish we hadn't done it. Therefore, widely watched experiment seems appropriate.

Health Savings Accounts seem highly desirable in themselves, particularly under the urgent circumstances of backing off from Obamacare and substituting Trumpcare, without exactly defining either one of them. HSA has been in existence for thirty years, have jumped through the numerous legislative hoops, and have been at least temporarily adopted by millions of people. Major businesses have apparently recognized this feature and changed their earlier resistance to an endorsement of voluntary trials within the health benefits system. People old enough to have Medicare are largely indifferent to this topic because they believe their medical financing is secure, but even this group is beginning to perceive that better health has created a much greater need for retirement reserves. Younger people for their part, have now received small accounts as an unexpected employer gift, and are asking each other what it's all about. The administrators of such accounts vary widely incompetence, with health insurance companies cautiously steering people to account managers, and account managers steering customers to high-deductible insurance managers. It is the nature of things that commissions of some sort are paid for referrals of business, which in turn reduce the effective income of customers. The McCarran-Fergusson Act pushes in the direction of control by fifty states, while the Constitution places the currency in the hands of a national government; it's only a guess which way things will fall.

Finally, the health financing crunch has added an element of urgency to a decision which would ordinarily take much longer. The casualties of the Civil War shifted sympathy away from states rights, but the health crisis forces re-examination of that decision. One glance at weekend traffic congestion around the nation's capitol convinces anyone that centralized control may be outgrowing its blood supply. United States congressmen are sleeping on cots in their offices rather than face the cost and strain of transcontinental commuting; this heart of centralized government has already become convinced that centralization has created big problems. Eventually, something must break this logjam, and devolution of powers to the states might be part of that solution. So, the problem is big, complex, and urgent. And the healthcare financing problem might well force a speedier resolution. The nation, however reluctantly, is about to address this issue at its roots, understands that any solution may go wrong, and probably is willing to tolerate some experimentation with fundamental structures like monetary standards, which would have international consequences. A monetary standard is so fundamental that experiments must be meaningfully large and inclusive, but they must also remain voluntary, in order to be modifiable or abandoned. The atmosphere of near-crisis is necessary even to come to a decision, and health financing happens to supply that ingredient.

Why Shouldn't Governments Ever, Ever, Own Common Stocks?

Events in the automobile business just happened to provide a recent demonstration that Robert Morris had been absolutely correct in jiggering the Constitution to frustrate the worst disasters latent in the Industrial Revolution. The unelected President of the United States during its formative trials, Morris knew what he was doing, did it parsimoniously and in public, and steered its legal system (at the Constitutional Convention) to devise a stable arrangement without further insight from his successors.

At that time, both the borrowing power of the new republic and its ability to start new businesses seemed limitless, leaving adequate room for businesses to raise working capital by selling shares of their ownership , while government raised capital by borrowing against this previously unrecognized capacity. So the deal was to confine government borrowing to the control of the people (i.e. Congress), in return for forbidding the government to control the slightest fragment of business ownership. Ultimately, the people also limited wars through this two-step process, since paying for wars was typically the main reason governments needed money. We could go to war if we wanted, but the populace had to be in favor of paying for it.

In the War of 1812 and the Vietnam War, Congress effectively withdrew its approval of the adventure, and those wars came to a negotiated end. By contrast, the Mexican and Spanish-American Wars were equally questionable on a moral level, but the population supported them until we won. Morris was apparently shrewd about this. In two and a half centuries, ours is the only republic to have survived so long. Gouverneur Morris (no relation) was the elegant legal draftsman of the Constitution, but he missed the whole point and later renounced it. By contrast, Robert Morris the businessman, philanderer, and land speculator, is seldom recognized for his Constitutional role, but the resulting masterpiece long outlives his personal reputation.

To get back to the automobile business, the Japanese Nissan Company, and the French Renault Company, were having trouble selling their small vehicles in the United States, where drivers prefer big gas guzzlers in spite of the efforts of President Obama to coax them into smaller cars. The two companies formed a business arrangement of some sort, under the leadership of an Egyptian CEO, who managed to strengthen the Japanese but not the French component. The Egyptian CEO then decided it would improve things to merge the two car companies, but the French President decided it was better for his political purposes to have the French company absorb the Japanese one, using the argument it would improve sales in the U.S. So he discovered the 15% ownership shares already owned by the French government created voting control, enabling him to increase French ownership to 20%. The story is as yet incomplete, but this much is enough to illustrate the confounding effect of political motives clashing with commercial ones. Robert Morris knew how to prevent it: only back the currency with money you can borrow in the marketplace. When borrowing dries up, you've reached the limit of lending power.

That system worked for a century, as we gradually expanded wealth and borrowing in tandem. It's possible we may now be reaching the limit of our collective borrowing capacity, or globalization may simply have thrown borrowing out of harmony with volatile business wealth. Either way, right now it would seem desirable to restrain further borrowing while resisting the temptation to overvalue its source.

Nevertheless, we visibly have idle cash in the economy. We here propose to enlarge the nation's working capital by putting some of this working capital to work, but basing it on private collateral rather than government borrowing power. That magic would be created by placing up to 18% of GDP in private hands through medically escrowed index funds, accumulated to support Health Savings Accounts, but fully fungible. A few would be willing, the rest of the 18% would be too timid. A long duration of escrow would ensure high long-term interest rates and serve as a mechanism of control which could be modulated upon signs of overheating, but it might take some time to learn how to use it. At times when more borrowing is undesirable, this borrowing capacity may be countercyclical, which is often to say a good investment. But at other times it would not necessarily be a bad investment unleveraged. It could theoretically represent a huge increase in the money supply and have to be regulated gradually; it is through regulation that political control might override the business one. It must have taken Robert Morris some time and experimentation to perfect his system; the same is true of this one.

PROPOSAL: Cautious Steps Toward Gradual Implementation

Suggested steps:

1. Price Discovery Only. Construct several reliable national and world-wide indexes of the (ownership common) stock of corporations above a certain size. Debate on how to evaluate ownership shares which are not for sale, family-owned businesses, etc. Identify and choose the characteristics to be used for a common standard, and how much they probably matter to the issue. The goal is to defend an index achieving the closest possible approximation to the aggregate real value of the base economy under consideration, as well as the world economy, and to disseminate their price discoveries widely. Nations which fail to achieve this sort of index may have to be excluded from participation.

2. Assessing the Effect of Long-term Escrow. When the product seems perfected, conduct several representative trials of index funds using this standard as an escrowed partial replacement of existing standards. The purpose is to see if price distortion occurs and why, and whether the new standard is superior, equivalent, or inferior in some way. It may or may not be desirable to test these conclusions by observing an effect of termination by later re-instituting it. Permit permanent switch-over by nations who wish to do so. Try to assess the underlying forces at work tending to deviate from accurate valuation, and to quantify their power.

3. Assessing the Effect of Non-Escrow as a Short-Term Surrogate. The purpose of long-term escrow is to force these funds to be long-term investments. Short-term funds would have

4. Assessing the Effect of Combined Escrow and Non-Escrow in Various Proportions. This would include a search for evasions, arbitrage, collusion and other distorting errors in design, and attempting to correct for them, if necessary.

5. If results Seem Favorable, use the results to promote voluntary implementation by nations of this standard for the conduct of international trade as a storage of value . The whole process might take several years.

Three-Way Rebalancing

Using the present subjective standard in place of gold or other independent monetary standard has a number of disadvantages. It leaves the pricing in the hands of the country which changes it, forcing other nations to make compensatory changes if the volume disturbs trade. It can then prompt discord, by disturbing other currencies, leading to a ripple effect. All of these changes can prompt nations to create artificial pricing, to the disadvantage of countries which attempt to maintain fair evaluations, potentially starting trade wars, or even actual ones. In the long run, it inhibits realistic pricing of goods.

Left to themselves, three forces seek a permanent equilibrium: the real price of international goods, prevailing interest rates between the affected nations, and internal interest rates between different goods or services within the individual nation. In the very long run, prices re-adjust toward equilibrium. But the short-run effects can be temporarily highly disruptive. That is, one or two of these changes may seem expedient, but the disturbance hurts other nations, and in the long run the original prices return to where they started. The disruption can sometimes be severe, and the industries which are rescued are balanced by those which are harmed. The usual temptation is for an aggressor nation to help its own failing industry by (artificial lower prices) harming similar industries in other nations; and later for the consumers within the injured nation to retaliate by harming some of its own consumers at first, but later shifting harm back to consumers within the aggressor nation if they can. Quite often it is innocent bystanders who are hurt the most, in opposition political politics, or in unfriendly nations. Someone always gets hurt.

Once More, Why Drag Healthcare Into This Mess?

Most people have little background in currencies and their squabbles. But everyone wants healthcare to cost less, Health Savings Accounts seem to offer promise, providing a useful introduction to much the same idea. Learning about one helps people understand the other. Although currency reform amounts to much more money, 18% of the gross domestic product is very large, and both reforms affect everyone with a common approach.

Add to that the walloping unfunded retirement cost of prolonging longevity with improved health, and the combined result might require more time than its simplicity initially suggests. The governing party seems to be putting its chips on Health Savings Accounts, big business is experimenting cautiously with it, and millions of people already have started small accounts. So kicking out illegal immigrants might help unemployment, lowering corporate taxes might bring overseas corporations back home, removing red tape might help small business, and passive investing might finance part of healthcare cost. Working backward, extracting a couple of percent from international trade might reasonably trigger an economic recovery. The public is getting strident, and it's time to take some chances.

There's safety in diversification. Four programs which might each add 2% to the economy are far less chance than one big gamble to pay off 15%. There's room in this program for three of the proposals to fail, and still have the survivor keep us from sinking. Reducing the goals of each will reduce the urgency for results. Slowing the pace will improve the designs. All of these four programs are more likely to fail because of implementation delays than because of faulty design. On the other hand, a single concept behind two or three of them will lead to success in one breeding success in the others. Foreign countries adopting one of the ideas will strengthen all of them, and only currency reform is based on a technology advance seemingly confronting the nation with foreign chaos if it fails.

We sometimes forget it is possible to succeed too well. The Bretton Woods Conference was necessary because America essentially had all the gold in the world. Therefore, nobody could buy anything we had to sell.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Change to something more affordable seems inevitable, no one really believes something so expensive can be given free to everyone. But perhaps in a democracy, it can be given free to a majority of the population. Since two-thirds of the world population is poor while we seem rich, perhaps the unfairness can be extended a few percents to include all Americans. Meanwhile, America seems to have an unspoken agreement to buy its way out of healthcare costs with research, so perhaps in a century, we can recover the indebtedness by spending too much. That's bunk, of course, but it makes a good slogan.

The Future of Index-fund Investing, Itself

|

| Bank Collapse |

An abundance of threatening international situations might unexpectedly lead to a banking collapse, but since every bull market "climbs a wall of worry", it isn't a threat unless it happens. The introduction of a new international currency is either never going to happen, or it is going to be needed without much warning. It's needed in the developing world, but there's a long way to go before it topples banking systems in the developed world. At the moment, nation-wide index funds might make a perfectly satisfactory currency substitute, like the Spanish pieces of eight. Index funds are tested and available in huge amounts and trusted by everyone who talks about them. They are growing fast and may eventually dominate choices unless something even better comes along. If something better comes along, it is hard to see why we couldn't let the market replace them as fast as people want to buy them. In any event, we have tons of gold as an inert reserve. The question is, will they hang around in their present form long enough to be a useful tool? At the moment, bitcoins are the popular rage to make people rich, but most people feel a secret currency is a good way to make people poor.

|

| Stock Certificates |

Of course, no one can answer such a vague question about a vague future for a vague development. But index funds are essentially nothing but bundles of stock certificates which are easy to buy and sell, easy to lock in a vault, and easy to carry. They have real intrinsic value which can change with the economy and whose value can be checked in an instant. If something better comes along, it's hard to see why you couldn't buy it with index funds. It's hard to see why two or more currencies couldn't co-exist, particularly if the co-existence was temporary and brief. It's hard to see why it couldn't be limited to central banks, who support local secondary currencies with instantaneous appraisals of the mark-up premium. On the other hand, it's hard to see why it couldn't be divided into subunits and carried around in everyone's pocket, if that's what is chosen to do. Since we got along with Spanish doubloons for centuries, it can be assumed it will serve the purpose. Since ownership is registered, it's even got one certain improvement: you can lose it or have it stolen, and still have a way of getting a replacement. In a sense, that was Robert Morris' contribution to currency theory: if a wooden boatload of gold sank, it was gone. But if a boatload of gold certificates sank, the underlying gold was still safe at home.

|

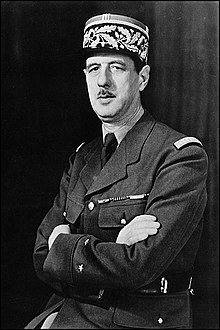

| Charles de Gaulle |

Resistance from those it would put out of work can safely be assumed. Just scratch any regulation, and you will find a lobbyist, usually very well funded. But the hardcore opposition would be from those who see that the currency has real value if you own it legitimately. Its value as a currency is that it is a real value, a piece of the economy, which you can carry with you anywhere. It, therefore, upsets the principle of national boundaries established long ago by the Treaty of Westphalia. If you want to defend this fact, you will say you could buy the country that way, by imagining a horde of "tourists" who open their knapsacks and demand what they bought, which is your economy. Some elderly people may remember the French battleship which Charles de Gaulle sent to New York harbor to demand his gold. It wouldn't take very long for that to be disruptive, as the more recent Irish experiment with lowered tariffs also graphically demonstrated with migrant corporations. Eventually, even the United States had to make itself competitive with the 12.5% tariffs of the Irish Republic. You will find, even though it is denied, that nations with weak economies don't want to be rescued by richer countries, so they will cook their books. Portable ownership of the means of production is not merely portable socialism, it is portable ownership of a corporation which may be indefensible legally, therefore leads to war if you try to exercise the right. So unless simple prevention can be devised, sovereignty is the one thing this money won't buy, even with Brexit. It might someday seem useful to prevent economic sovereignty as well, and for that, we must look to what the European Union devises for its individual component nations since they don't want to adopt the American one. With the exception of the Civil War, we managed to buy our way out of trouble by having rich states support poor ones, since we are all Americans, right? Until we reach the point of industrial states getting along with slave states, it would be better to have national currencies, based on national economies, type unspecified.

|

| Treaty of Westphalia |

Until someone figures out a solution to that issue, a confederation of national currencies based on index funds is about the best we can offer as a short-term solution. You can gamble on long-term stability, but it's your risk to do so, just as it is today. Short-term is worth something substantial, however. Reducing the cost of trade would almost surely inject several percents of GDP into everybody's economy, net of the cost of doing it. It should be the basis of a bull market, for quite a while.

The Future of Health Savings Accounts--Lifetime Accounts?

Remnants of a Medical Past

For thirty years this primitive HSA widened the band of lower-middle-class people able to afford their own healthcare. Another (shrinking) band of poor people with trouble paying full cost always remained, however, provoked by rapidly rising healthcare costs. For many people, the full cost was obscured by neglecting to fund the resulting retirement cost of improved longevity. For those with bare-bones coverage, however, the added cost was added cost. When retirement funds eventually ran out, distinctions didn't make much difference to people with other things on their minds. In both cases, added longevity was a serious hidden cost of improving healthcare, and those who didn't know what to do about it had that incentive not to notice. Linkage to employment crippled employer approaches, such as ERISA, whereas balancing the federal budget limited rising retirement subsidies to the poor. Using big data or little data, it is nearly impossible to see a way to keep such revenues and expenses in national balance over a period of a century from birth to death.

For those without outside support, HSA's were a sort of Christmas Savings Fund of reserves built up by young people, to pay for even anticipated future health costs. But that's not all they covered. By a quirk of the statute, any funds left over in an HSA at the time of joining Medicare, reverted to IRAs and could be spent for anything. Those who had considerable medical spending, however, probably had lessened longevity, whereas those with unusually robust health were the only group who actually had a mechanism for funding lengthened retirements. (In other sections, we discuss how some extra money was actually created by this system.) But even the Health Savings Account beneficiaries did not have an automatic total re-balancing system, except to the extent that individual savers collectively (and inadvertently) kept income and expense in aggregate balance. Similarly, any system yet to be devised in which a bureaucracy uses these funds as a piggy bank is doomed to political danger. The Federal Reserve is fairly successful at maintaining independence by the obscurity of behavior, but even it becomes visibly less independent of political pressure, year by year. It is a possibility politician will figure out how to get around the Fed, long before the public does.

Initial low costs and later heavy ones, combined, describes the cost curve pretty well, bending upward about age 55. It's also augmented by wasteful costs proving to be mostly small, handled more cheaply by the client than through a remote insurance company. Start with ensuring the most expensive items, try to pay the cheap ones, out of pocket. Deductibles might be flexible, and although some will always be too poor to afford them, younger people might have time enough to recover.

Co-pay was explored by HSA developers, but it never completely goes away until the costs are eliminated, mixing it relentlessly with high-cost (ie insured) charges and small ones in the deductible. Co-pay became either became a second insurance policy, which implied a separate administrative cost, or a bad debt for providers. Everybody, therefore, had both large claims and small ones at the same time, increasing overhead when it really served no cost-restraining purpose. Since the deductible served the accordion idea just as well, it seemed better to use it alone, not double its administrative cost. And then the idea struck that attaching it to a "Christmas Savings Fund" would allow young people to accumulate the missing deductible within the account, gathering interest in the process. Furthermore, once the amount of the deductible accumulated, the poor person who owned it had gradually assembled "first dollar coverage", but the premium for the deductible insurance would not be increased by it. In effect, the individual would then be self-insured for small medical costs, transferring this cost for the insurance company into a profit for the client. Later on, when Medicare took over heavy expenses for everyone, there might be money accumulated in the account which would instead help pay for retirement. As experience actually accumulated, the contrast between first-dollar insurance which encouraged frivolous spending, and the interest-bearing account which rewarded frugality, reduced the insurance cost by 20-30% and made certain the client (instead of the insurance company) got the benefit of the cost reduction. That summarized the original Health Savings Account. It was cheaper, discouraged frivolous spending (or permitted it with a minimum of investigation), offered costless first dollar coverage, and created a retirement savings vehicle which no other health insurance included. It even sorted the people with a lot of sickness from the ones who were lucky enough to need more retirement funding, and who eventually needed retirement funding -- the most.

As experience gradually accumulated, it became evident other desirable features were latent in a very simple-sounding system. As one form after another of government funding for the poor emerged from Washington, some of the theoretical objections to that approach made an actual appearance. The double insurance overhead implicit in co-payment, and the 80-20 split which did not put enough "skin in the game" to restrain spending exposed that larger amounts really did occasionally pinch some people. Some did actually drop their insurance. The idea that better health inevitably led to longer retirement, had never embraced the notion that life expectancy might increase, as it did, by thirty years. Indeed, some estimates place the retirement cost at five times the cost of the healthcare which provoked it. New drugs might make an occasional appearance, but no one expected new drugs and more luxurious hospitalizations to reach the point where they cost five times what an average year of retirement savings might produce. Retirement was continuous, sickness was episodic.

One way or another, health costs responded to the traditional health payment system by making its cost into a curse. An alternate system which envisioned paying at least half of these costs without rationing, could not be brushed aside, at least just had to be examined. The movement of 4 trillion dollars from stock-picking to index investing in a single year, got lots of attention, especially when it happened to several "passive" funds at a time when just about everything else was doing poorly. Inevitably, the money accumulating in Health Savings Accounts found its way into index accounts, and theory became the experience. Extrapolating into the future, even a modest shadow of such results would greatly help our health-care deficits. Combined with a century of future scientific progress eliminating disease costs, we might actually survive what was beginning to look like a well-intentioned blunder. For now, we'll leave the details to Congress and other policymakers. It may disappoint us somehow, or it might exceed our expectations. But when you start talking trillions of dollars, you know the idea has its own momentum. We haven't even started to test the potential of enlarging the idea.

So this book throws an idea on the table. Ever since the Bretton Woods conference, the elimination of the gold standard has been in the cards. There's a limited amount of gold on earth, and to substitute a committee opinion is equally unlikely to resist the political pressures on it. We need a substitute for gold which enlarges and contracts with the economies of the earth, which is internationally valuable and responds to local problems in an individualized manner. Why not explore the idea of using national total index funds as a monetary standard? If it doesn't work, there are several tons of gold buried in Fort Knox as a back-up.

The Future of Individual Equity Index Funds ("Passive investing") As a New Gold Standard

Joseph Schumpeter's famous slogan "Destructive Innovation" fails to mention an important feature: sometimes, the cost of destruction can be greater than the profits from the innovation. The destructive effect makes its appearance early when the innovator is likely to have the insufficient startup capital to overcome a stagnant but politically powerful existing alternative. A suspicion arises that undeveloped markets, lacking "national champions", might actually have an advantaged location to perfect and exploit an innovation.

Kenya seems to present examples of several of the issues. Regardless of whose idea it was, the British but Los Angeles Headquartered Qualcomm Corporation seems to have recognized the potential of electronic banking and hired IBM to develop the technology. Ignoring the British and American markets, they started the M-Pesa Corporation in Kenya and Tanzania, where they quickly assembled 15 million customers producing a 27% profit margin, in spite of a 10% rate of attrition by fraud. Competitors are experiencing similar mixtures of success and failure in India. After the kinks are worked out in Africa, Qualcomm presumably might then be in a position to exploit its experience toward defeating conventional banking competitors in the developed world. Its recent stock market decline may suggest fierce competition even in darkest Africa, or it may suggest an investment bargain. But it illustrates the changing issues within technology innovation.

According to reports, M-Pesa eliminates the cost of branch banks by combining the ideas underlying Bill-Pay and Pay-Pal. Others can do the same. Africa may have few strong banks but has millions of wireless telephones. The customers deposit money by phone by increasing the phone charges and then direct its payment by phone. Leverage is developed by outsiders depositing extra money to lend, and thus the basics of banking are assembled inexpensively. A charge to use the system is added, with a surcharge for paying the bills of non-members. The system attracts fraud, but apparently, there are enough honest people starved for banking services, that profits absorb the cost. Bitcoin employs different technology but many of the same concepts, so conventional branch banks are not the only competition. Unless they change ancient ways, somebody is eventually likely to upend conventional banks in developed nations, although it may not necessarily be Qualcomm.

So, many of the objections to substituting new currencies for higher-cost branch banking are surely going to be tested by some system, anyway. Branch banking has been successful for a long time, so it is not likely to collapse because of internal contradictions alone. Innovative competitors are going to have a rough time overturning a useful system, need not be addressed here, so we confine this overview to the peculiarities and specific advantages of a currency replacement by index funds. Are they here to stay?

15 Blogs

FRONT STUFF::A New Currency? Equity Savings Accounts.

Currencies Decided By Committee, or Self-Balancing?

New blog 2017-02-19 20:31:56 description

Currencies Owned by Nations, or by People?

Passive Investing With Total-Market Index Funds

New blog 2017-01-11 03:53:57 description

Achieving Meaningful Volume Quickly But Tentatively

Why Shouldn't Governments Ever, Ever, Own Common Stocks?

PROPOSAL: Cautious Steps Toward Gradual Implementation

Once More, Why Drag Healthcare Into This Mess?

The Future of Index-fund Investing, Itself

The Future of Health Savings Accounts--Lifetime Accounts?

The Future of Individual Equity Index Funds ("Passive investing") As a New Gold Standard