2 Volumes

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia Places

New topic 2017-02-06 20:19:14 description

Easter Sunrise in Philadelphia

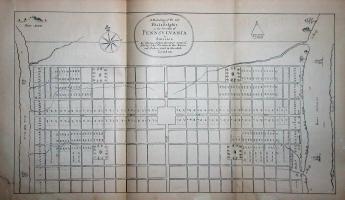

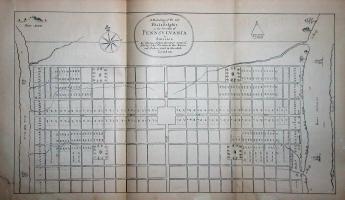

William Penn first advertised the layout of his new city in a book by Thomas Holmes published in 1683. Records are lacking about how these plans developed, how much of the idea came from Holmes, how much of the rest was carefully planned, versus how much just worked out. There's not much doubt the streets were laid out in a square grid. And the "numbered" streets all run North and South, following the compass path. These two ideas make it inevitable that the cross streets named after trees would run due East and West. That's enough for a sketch, and whether anyone thought about it further is not clear.

However, the consequences of this layout are that if you looked East at the sunrise on March 21, the rising sun would be exactly framed within the streets, whether they are lined with trees or lined with skyscrapers. That would make quite an Easter morning, with every cross street in the city pointed exactly but briefly at the rising sun.

|

Let your imagination run on this idea, a little. The exact day of Easter varies a little because of the Biblical definition of Passover to which it is linked, and the Eastern Orthodox Easter varies from that. With Philadelphia providing a forceful example of the utility of using an astronomical definition which was probably the original basis for all the religious traditions, maybe it would even become easier to remember just what date Easter is, each year. Or, perhaps things would go haywire the way things did in Brazil. Magellan sailed into what looked like the mouth of a big river on January 1, 1520, so he named it the Rio de Janeiro. They have an enormous Mummers-like celebration down there in Rio every New Year's, in spite of the awkward fact that it's just a big bay, there is no river there at all, and the dates for Christmas are astronomically a little mixed-up too.

Well, to get back to William Penn, his streets run North and South from Magnetic North. Even though it's quite a natural mistake to make in the Seventeenth Century, that's six degrees off from True North. So the astronomical transformation of Philadelphia into one big humongous Easter sunrise celebration never happened.

We'll never know for certain, but, on reflection, that may be just as well.

New Castle, Delaware

New Castle is easy to get to, but hard to find. It's right on Delaware Bay, at the start of the old National Road (Route 40), next to two huge bridges, a few miles from the main north-south turnpikes, a couple of miles from an airport -- and lost in a sea of suburban housing and highway slums. It's lost, so to speak, in plain sight.

|

| New Castle, Delaware |

And yet it is a perfect jewel of early American history and architecture. It's just as attractive and historically important as Williamsburg, Virginia, except these buildings are not reproductions, but the real thing. The town says it was founded in 1651 by Peter Stuyvesant, but Peter Minuit in 1638 could make a claim to be even earlier. Located at the narrow neck of the funnel that is Delaware Bay, it was a natural place to start a colony, eventually to be the capital of the state. The Delaware River makes a rightward turn at that point, and creates a river highway all the way to Trenton. But a few miles upriver at Tinicum, now Philadelphia International Airport, the river started to fill up with islands and snags; was it better to locate upriver or downriver from the narrows? New Castle was placed downriver.

|

|

New Castle's courthouse is the epicenter of the arc from Maryland to the Delaware River. |

But in 1777 the British fleet came to visit with hostile intent, and New Castle could look out the windows along the Strand right into the mouths of ships with twenty or thirty cannons pointing at them. Philadelphia, on the other hand, was protected upriver by a series of mud flats and barricades at Fort Mifflin that could quite effectively bar passage to enemy sailing ships. Delaware got the point, and shortly thereafter, the capital of Delaware was prudently moved to Dover, while even the county seat of New Castle County was moved to Wilmington. New Castle had a big fire in 1824; rebuilding afterward accounts for much of the present uniformly Federalist architecture. The final nail in the commercial coffin of the town was driven by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which just by-passed the town. For a century, this little architectural jewel just sat there in the fields, until the narrow neck of the Delmarva Peninsula became such a transportation crossroads that the fields filled up with construction more appropriate to Los Angeles. New Castle disappeared, without moving an inch.

|

|

100 Harmony St., New Castle, DE 19720 (302) 328-2413 |

For fifty years in Colonial days, the rector of Immanuel Episcopal Church in New Castle was one George Ross. His son, also named George Ross became a lawyer in Lancaster and signed the Declaration of Independence. His widowed daughter, Gertrude Ross Till married George Read, a lawyer in New Castle who also signed the Declaration. And, a third signer Thomas McKean, lived two houses away. George Read had studied law under John Moland, whose house served as Washington's headquarters in 1777.

The northern border of Delaware is a semicircle, with a twelve-mile radius based on the cupola of the New Castle courthouse. It was originally the border of New Castle County, and it proved to be slightly imperfect. In the first place, it extended across the Delaware River into New Jersey, but it was a nuisance to go there, so that segment of land was abandoned to New Jersey. However, the legal border of the State of Delaware, therefore, extends to the high-water bank of the river on the New Jersey side, rather than running down the middle of the river. The significance of this curiosity appeared when the Delaware Memorial Bridges were built, and all of the tolls go to Delaware, instead of being split between the states as is more customary. The other problem with the semi-circular arc was that three lines meet at the northwestern corner of Delaware, and each was defined in its own way. The Mason-Dixon line goes due east-west, the border with Maryland goes north-south, and the idea was that the semicircular arc would meet the other two lines at a point. However, the instructions could be read in two different ways, leaving a little "wedge" of territory that could be reasonably said to lie in either Pennsylvania or Delaware, depending on the sequence of describing them. This was certainly a circumstance where any decision was better than no decision, but it took until 1921 for the states to harrumph their way to a final pronouncement. In the meantime, the disputed wedge of land was a good place to have duels, cockfights and other matters of questionable legality.

REFERENCES

| Lewes, Delaware: Celebrating 375 Years of History Kevin N. Moore ASIN: B006DL8TC6 | Amazon |

The Houses in the Park

|

| Strawberry Mansion |

Fairmount Park is said to be the largest park (7000+ acres) within the limits of an American city, and in fact, maybe just a little bigger than the city can afford to maintain. It was established in the middle of the 19th Century through the efforts of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to reverse the Industrial Revolution's relentless pollution of Philadelphia's Schuylkill River and the water works. The waterworks were built in 1801 in the mistaken belief that Yellow Fever was caused by pollution; Fairmount Park more accurately responded to the idea that Typhoid Fever was waterborne from upstream pollution. Lemon Hill, the nearby mount containing Robert Morris' Mansion, was purchased to expand the reservoir capacity of the waterworks and thereby made the Art Museum possible where the reservoirs were originally located.

The Park has long constituted a symbolic interval between center city and the suburbs. Since the construction of the river drives and later the expressway, the commute along the river amidst trees and parkland has made an entrance to town a pleasant experience. If the town planners had been able to foresee automobile commuting, they might have anticipated that the sun would be in the driver's eyes coming East during morning rush hour, and in his eyes as he went home toward the West in the evening. Driving safety might perhaps have been impaired by the tendency of this glare to direct attention to the park rather than straight ahead, but nevertheless redoubles the effect of the park views as a daily aesthetic experience. Even the pollution idea had its ambiguous side since animals increase the bacterial runoff from their grazing areas, and the original houses in the park had many pastures. Strip mining, however, allows mineral contaminants to be washed by rain into the watershed. The city waterworks today extract nearly 800 tons of sludge from the water supply, daily. Whatever the effect downstream, the high ground had less malaria and less typhoid than swampy lowlands, so many of the original houses were useful summer retreats for city dwellers during the early years of the city.

The park is governed by the Park Commission, and at one time had its own police force, the fourth largest police force in the state. Started in 1868, the Park Guards changed their name to the Park Police and then became part of the Philadelphia Police in 1972. The original 28 officers had grown to 525, had their own police academy and a proud tradition. It seems very likely that some deep and dirty politics were played in this shift of authority, and it might be a fair guess that some bitterness still survives in the circles who know and care about these things. In 2008 a scarcely-noticed rule change gave the Park to the City Department of Recreation, thus placing it just a little closer to ambitious real estate development. Our present concern, however, is with the houses in the park.

There are seven of them, kept up and maintained by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Guided tours are provided intermittently by the museum, but since funds are limited only three of the houses are open year round. The others are equally worth a visit but unfortunately, are closed during the height of the spring flowering season. Two of the year-round houses represent the two extremes of Philadelphia culture, since Mount Pleasant was owned by a buccaneer ("privateer") named McPherson who lived at the height of 18th Century elegance, while Cedar Grove was originally a Quaker farmhouse of the greatest simplicity consistent with honest comfort, a style which persisted relatively unchanged until late in the 19th Century. Benedict Arnold and Peggy Shippen looked at Mount Pleasant with an eye to purchase but never lived there because they were called away by national events. With the addition of modern plumbing and air conditioning, Mount Pleasant would be an elegant place to live, even today. McPherson had to sell the place to pay his debts, whereas the Wister and Morris descendants of Cedar Grove still populate the Social Register in large numbers. The two houses completely typify the underlying philosophies of the two leading Philadelphia classes of leadership. One group measures itself by how much it spends, the other group measures success by how much it has left.

REFERENCES

| Treacherous Beauty: Peggy Shippen, the Woman behind Benedict Arnold's Plot to Betray America: Mark Jacob:978-0762773886 | Amazon |

Delaware's Court of Chancery

|

| Chancery |

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's the county seat so it has a courthouse on the town square, with little roads running off in several directions. The courthouse is surprisingly large and imposing, even more, surprising when you wander through cornfields for miles before you suddenly come upon it. The county seat of most counties has a few stores and amenities, but on one occasion I hunted for a barbershop and couldn't find one in Georgetown. This little town square is just about the last place you would expect to run into Sidney Pottier and all the top executives of Walt Disney. But they were there, all right, because this was where the Delaware Court of Chancery meets; the high and mighty of Hollywood's most exalted firm were having a public squabble.

Only a few states still have a court of Chancery, but little Delaware still has a lot of features resembling the original thirteen colonies in colonial times. The state abolished the whipping post only a few decades ago, but they still have a chancellor. The Chancellor is the state's highest legal officer, and four other judges now need to share his workload, which was almost completely within his sole discretion seventy-five years ago. In fact, the Chancellor usually heard arguments in his own chambers, later writing out his decisions in longhand. The Court of Chancery does not use juries.

Going back to Roman times, the Chancellor was the highest office under the Emperor, and in England, the Lord Chancellor is still the head of the bar in a meaningful way. Sir Francis Bacon was the most distinguished British Chancellor and gave the present shape to a great deal of the present legal system. A court of Chancery is concerned with the legal concept of equity, which is a sense of fairness concerning undeniable problems which do not exactly fit any particular law. The Chancellor is the "Keeper of the King's conscience" concerning obvious wrongs that have no readily obvious remedy. You better be pretty careful who gets appointed to a position like that, with no rules to follow, no supervisor, no jury, dealing with mysterious issues that have no acknowledged solution.

|

| George Read |

Delaware's Court of Chancery evolved in steps, with several changes of the state Constitution over a span of two hundred years. As you might guess, a few powerful chancellors shaped the evolution of the job. Going way back to 1792, Delaware changed its Supreme Court from the design of its Constitution, and George Read was the new Chief Justice. However, it was all a little embarrassing for William Killen, who had been the Chief Justice, getting a little old. Read refused to have Killen dumped, and in this he was joined by John Dickinson, who had been Killen's law clerk. So Killen was made Chancellor, and a court of Chancery was invented to keep him busy.

Under a new 1831 Constitution, the formation of corporations required individual enabling acts by the Legislature and limited their existence to twenty years. However, the 1897 Constitution relaxed those requirements and permitted entities to incorporate under a general corporation law and allowed them to be perpetual. By this time, other states were distributing equity cases to the county level, but Delaware was too small to justify more than a single state-wide Court. That court was attractive to corporations because it could become specialized in corporate matters, but retained a pleasing number of equity cases among common citizens, thus retaining a folksy point of view. In unique situations or those without a significant history of public debate, it was thought especially desirable to strive for unchallenged acceptance of the court's decision.

But other states thought they could see what Delaware was up to. In 1899 the American Law Review contained the view that states were having a race to the bottom, and Delaware was "a little community of truck farmers and clam-diggers . . . determined to get her little, tiny, sweet, round baby hand into the grab-bag of sweet things before it is too late." However, that may be, corporations stampeded to incorporate in the State of Delaware, and the equity of their affairs was decided by the Chancellor of that state. In one seventeen year period of time, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Chancellor only once.

Chancery's jurisdiction was complementary to that of the courts of common law. It sought to do justice in cases for which there was no adequate remedy at common law.  |

| A. H. Manchester Modern Legal History of England and Wales, 1750-1950 (1980) |

Some legal scholar will have to tell us if it is so, but the direction and moral tone of America's largest industries has apparently been shaped by a small fraternity or perhaps priesthood of tightly related legal families, grimly devoted to their lonely task in rural isolation. The great mover and shaker of the Chancery was Josiah O. Wolcott (1921-1938), the son and father of a three-generation family domination of the court. Most of the other members of the court have very familiar Delaware names, although that is admittedly a common situation in Delaware, especially south of the canal. The peninsula has always been fairly isolated; there are people still alive who can remember when the first highway was built, opening up the region to outsiders. Read the following Chancelleries quotation for a sense of the underlying attitude:

"The majority thus have the power in their hands to impose their will upon the minority in a matter of very vital concern to them. That the source of this power is found in a statute, supplies no reason for clothing it with a superior sanctity, or vesting it with the attributes of tyranny. When the power is sought to be used, therefore, it is competent for anyone who conceives himself aggrieved thereby to invoke the processes of a court of equity for protection against its oppressive exercise. When examined by such a court, if it should appear that the power is used in such a way that it violates any of those fundamental principles which it is the special province of equity to assert and protect, its restraining processes will unhesitatingly issue."

That is a very reassuring viewpoint only when it issues from a person of totally unquestioned integrity, a member of a family that has lived and died in the service of the highest principles of equity and fairness. But to recent graduates of business administration courses in far-off urban centers of greed and striving, it surely sounds quaint and sappy. And many of that sort have found themselves pleading in Georgetown. Just let one of them a bribe, muscle, or sneak into the Chancellor's chair someday, and the country is in peril.

Riverline: Camden and Amboy Revival

The RiverLine, a sort of diesel-powered overgrown trolley car line, has just opened on the Conrail tracks from Camden to Trenton. It runs every 30 minutes in both directions but unfortunately stops at 10 PM to let Conrail run freight trains at night. That's almost a perfect fit for the two operations, although it can leave baseball fans stranded at a night game at Campbell Park, or concertgoers at the Tweeter Center. The trains are running fairly full, partly because of their novelty, and partly because of the initial decision not to collect the $1.10 fare on Sunday, but mostly because the Riverline proved to be a better idea than anyone realized it would be. It's considerably cheaper for Philadelphia commuters to Wall Street to take the Riverline and transfer to New Jersey Transit at Trenton, for one thing. Even Amtrak encourages that, because high gasoline prices have filled up the Amtrak trains.

It's well worth a historical excursion on the RiverLine, which runs on the former right of way of the Camden and Amboy RR, the first railroad in New Jersey, chartered in 1830 by Robert L. Stevens. A genius of many talents, Stevens invented the iron rail which looks like an inverted "T," held in place by a system of plates and broad-headed spikes. The system is still in use today. Stevens also devised the use of wooden cross ties rather than granite ones, finding they resulted in a smoother ride. In 1834, he joined forces with another many-talented genius, Robert F. Stockton, who had earlier constructed a canal from New Brunswick to Trenton. Stevens then built a railroad beside the canal, subsequently extending it from Trenton to Camden. Stockton ran ferry boats from Perth Amboy to New York, and from Camden to Philadelphia. The full trip from New York to Philadelphia took nine hours, a remarkable improvement over the horse-drawn competition. The partnership also got the Legislature to confer monopoly rights, so the arrangement was highly profitable as well as an engineering marvel. Sixty years later, the Sherman Act would declare such monopolies to be crimes, but in 1830 they were considered a clever way for Legislatures to stimulate risky investment. The Pennsylvania Railroad bought the partnership and its monopoly in 1871, but preferred to bridge the Delaware River at Trenton, so the towns and track along the Jersey side of the river soon dwindled away. The RiverLine now provides a pleasant one-hour excursion along the riverbank, down the main streets of some cute little towns, past some remarkable woods and wilderness up near Trenton, and past Camden's urban revival at the other end.

Rail Station at Broad and Washington

Washington Avenue was called Prime Street before the Civil War and was an important trans-shipment center for the whole country. Rail traffic, coming down from New York and New England, came through New Jersey on the Camden and (Perth)Amboy RR, disembarked, and ferried over Delaware to the foot of Prime Street/Washington Avenue. Passengers then took horse-drawn cabs up Prime Street to Broad, or else they walked. At that point, travelers bound for further South would enter the imposing Rail terminus of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore RR, to re-embark. Philadelphia hotel operators hoped they would stay overnight; Philadelphia merchants hoped they would just transact their business locally, then go back home. Taking nine hours from New York, it was an inefficient transportation method by today's standards, but the Prime Street interruption served local economic purposes, which Chicago keeps in mind, even today.

Sketch map showing the area between Philadelphia and Baltimoreindicating drainage, cities and towns, roads, and railroads.

Consolidated February 5, 1838.

The interruption also worked the other way, inducing Southerners to go no further North with their business, thus strongly contributing to pro-Southern sympathies before the Civil War. Philadelphia was indeed the most northern of the Southern cities until the 1856 Republican convention (at Musical Fund Hall) started to remind other Philadelphians that the anti-slavery Quakers perhaps had a point. Even so, pro-Southern feeling in Philadelphia was wide-spread, even in the early months of the war.

|

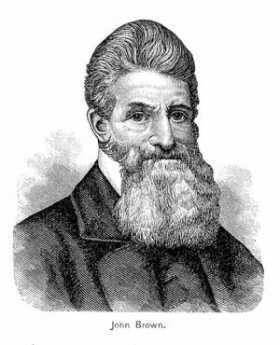

| John Brown |

For example, in 1859 John Brown's body was brought forth on the PWB railroad, precipitating a pro-Southern riot at the Broad and Prime Station. There was a second riot the following year.

During the Civil War itself, the PWB railroad was a major military transport, carrying military supplies and troops to the battles, and bringing the many wounded troops back home for treatment. Quite a large military hospital was built across Broad Street from the rail station. All in all, the corner of Broad and Prime was a major center of the war, and may well have been one of General Lee's objectives when he launched the invasion that got stopped at Gettysburg.

|

| B& O Railroad |

After the Civil War was over, attention was finally paid to the need for better North-South rail transport along the Eastern Seaboard. Up to that time, European investment had pushed American railroading in an East-West direction. The Baltimore and Ohio were aimed at the Mid-West, while the New York railroads aimed at Chicago and beyond. Local politics in the seaboard cities tended to keep the competitors from linking and thus potentially capturing trade between the manufacturing North and agrarian South.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore was the key link in the series of mergers which created the dominant Pennsylvania Railroad. Bringing northern traffic in through North Philadelphia to the new 30th Street Station,

|

| 30th Station |

and then linking it to the stub of the P, W, BRR, the way was being paved for Ascella Express trains to shoot from Boston to Washington, perhaps eventually to Florida. The side-track from West Philadelphia to Broad and Washington was allowed to wither, and of course, the whole Camden and Amboy RR became scarcely more than a trolley line All that was left as a challenge to the Pennsy was to get past B and O obstructionism in Baltimore. This last step was finally accomplished with the discovery of some legal loopholes related to an existing right of way for a local commuter line in Baltimore, where permission for a branch line was broadly interpreted, and a surprise tunnel dug to link it up to the other parts of the Pennsy. Amtrak passengers nowadays usually move through the Baltimore tunnel systems without noticing them, but occasionally a train breaks down inside the tunnels. Then, they prove to be rather dark and damp as the passengers with their laptops are transferred to another train.

Retirement Communities (CCRC)

Let's confess my meager authority to generalize about trends in retiree convalescence. When I graduated from medical school in 1948, average American longevity was twelve or fifteen years shorter than today, and most assumptions rested on it's remaining the same forever. Someone who reached eighty was really old, obviously facing a prompt decline. Today, essentially everybody lives to be eighty. We only half-expect such long life, which is modest of us, and only halfway plan for it, which is foolish.

Picking the right CCRC is as hard as picking the right spouse.

|

In 1950 a general practitioner in Haddonfield, NJ called for help from the son of one of his patients. The son was a doctor on the staff of the Pennsylvania Hospital, where I was finishing my internship. The GP hadn't had a vacation for twenty years and wondered if one of the graduating internets might take his practice for a month. I volunteered and then learned about retirement in a prosperous suburb. My employer had many tasks, among them a schedule of ten or twenty monthly house calls. There may have been some male patients on those rounds, but all I remember were old ladies living on the third floors of big old houses. I wasn't expected to do very much when I visited, at least by Emergency Room standards in the hospital. The families with whom the grandmothers were living wanted to be reassured that nothing was neglected. They also wanted to form their own assessment whether the doctor really knew them, and would come immediately if needed.

|

| Doctor House Call |

My next insight came a few months later when another doctor on the staff of the hospital had a heart attack; the Chief of Medicine gave me the time off to take care of this practice while the doctor recovered. When I first arrived at the door of the brick Philadelphia row-house where the doctor had his office, I was met by his nurse already wearing a raincoat, handing me an umbrella. We visited ten or fifteen other row houses along the neighboring streets, where to my amazement I found patients with oxygen tents and intravenous infusions. If the patients needed blood tests or electrocardiograms, the nurse arranged for them to be performed at home. Drugs by injection were administered, hospital-like bedside charts were maintained. This was a working-class neighborhood substitute for hospital care, but I was astonished to see how adequate it was. By this time, we had many resident physicians at the hospital who had seen service in the war and returned for specialty training; they regaled us at the lunch table about treating major illnesses -- in a tent. This wasn't the Civil War we were talking about, it was 1950.

Fifteen or twenty years later, my personal situation had improved; Medicare had arrived in 1965, but I was in practice as a center-city specialist and hardly noticed the new insurance system. But I did have three patients who insisted on being treated at home, which even by then had become an unusual arrangement. All three lived in condominium apartments in buildings with dining rooms on the main floor which would send up take-out dinners. All three patients had live-in nurses and hospital beds rented from an agency. One spinster lady absolutely refused to be treated in a hospital, because the Queen of England set up a little hospital in her palace when she needed it, and this lady said for practical purposes she had as much money as the Queen. Because she was dying of cancer, I resisted this idea, but if you had seen Katherine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story you got the helpless feeling this dame was going to have her way. We called in laboratory and x-ray services as needed, administered injections, maintained a hospital chart. In this case, when I made a house call, her chauffeur would pick me up and deliver me, helping to ensure my promptness. Her lawyer and I kept careful financial records of the experience, which was new to him, too. After she died, we totaled it up and discovered with astonishment that the whole thing had been cheaper, a lot cheaper, than going to the hospital. Since she left a sum to the hospital in her will, even the hospital was pleased.

Well, nowadays there are more than fifty retirement communities scattered around the periphery of Philadelphia, many or most of them sponsored by Quakers. It's a national movement, and there are people in California who feel they had the idea first. There are now enough of these organizations to permit some classification of them into types, which mostly follows the sort of community model they resemble. There are some that look and are run like college dormitories, some that resemble convalescent homes, some are very like big-city apartment condos, and some behave like resort hotels. One of them, the Kearsley, sits in the middle of the Bala golf course, attempting to provide the first-class service to indigents by using existing government assistance programs, but has lately had to fall back on the Episcopal Church for financial help.

|

| CCRC |

Since a financial shadow hangs over all of them, it should be mentioned first. Every person in a retirement village is eligible for Medicare and Social Security, and with the help of a social worker can fall back on less-known assistance programs. It's impossible to ignore the existence of these funds, but most unwise to depend on them. As the age and number of retirees constantly grow, state and federal governments are starting to draw back from initial generosity. Laws have passed that a CCRC resident may not be evicted for non-payment of debts, so the institutions have had to impose conditions which guarantee them payment from new entrants in the case of later inability to pay. The risk remains that clients who entered before the rules were imposed, can only be extricated by going before Congress and raising a piteous cry on bended knee. Such laws and embarrassments vary from state to state, and from year to year, but unstable finances destabilize any business. When the customers all depend on their savings, and average investment experience is a drop of 30-50% in the past couple of years, no one escapes anxiety.

Although there must be college courses in how to administer a CCRC by now, current administrators are drawn from the environment the place mostly resembles, so the resemblance gets stronger. The former manager of a country club tends to neglect the infirmary; the former directress of a convalescent home doesn't notice institutional food. If the administrator treats customers as complaining nuisances, you get one kind of war; if the board of directors is accustomed to ruling corporations by dictate, you get another. Mainly, these institutions differ from models of other institutions by the degree to which they have active volunteers in charge. The inmates may run the asylum, but only if they become useful volunteers. A curious distinction evolves between those CCRCs which emerge from college alumni associations and those which are sponsored by churches. University faculties are not accustomed to, nor generally sympathetic with, teamwork. Every faculty member is on his own career path, which he hopes leads straight upward; teamwork to them is a code term used by business executives to imply blind obedience, Charge of the Light Brigade, or worse. Church groups, on the other hand, prize volunteerism. In a church environment, the proposal that Let's Have a Picnic is supposed to be met with a chorus of Great, I'll be Glad to Bake a Cake. Church-sponsored CCRCs, therefore, are generally more adaptive to innovation in a formless society. University groups have camaraderie and complaining, but little follow-through. By contrast, business people know what you are supposed to do, you are supposed to make something happen. Church volunteers want to know how they can help. Paradoxically for that reason, the more evidence of golf clubs around the place, the more likely it is to be innovative.

Let's return to the point, succinctly. Life-threatening and potentially convalescence-requiring medical conditions are destined to segment increasingly into Medicare, to the point where what remains outside of Medicare is elective, preventive or outpatient. Obstetrics is an exception, remaining more naturally part of the hospital than the CCRC. The rest of medical care thus seems inclined to migrate toward the suburban ring of retirement communities. The more natural transportation flow is for younger people to travel to either a hospital-centered medical cluster or a CCRC-centered cluster, not for frail old folks to leave the convalescent environment except for major surgeries from which they soon return to their infirmary. It doesn't have to be that way, it just seems like the natural arrangement.

Probably the main reason it doesn't work that way today resides in the Medicare law. The 1983 amendments restrained inpatient reimbursement much more than outpatient care or home nursing care, and consequently, inpatient costs have risen 18% in five years, compared with 47% for outpatient. Outpatient care is not migrating toward retirement communities because hospitals need revenue. Somehow, it seems easier to modify these reimbursement rules than to upend suburban CCRCs and relocate them next door to an urban hospital. If the payment rules become reasonable, the system will readjust its geography in a reasonable way, without coaxing.

Surely, non-residents of the CCRCs are destined to wish to convalesce in the spare beds of CCRC infirmaries which should then treat younger people as a much-needed revenue source; any licensing requirements which block this seem unreasonable. Medical hardware,-- x-rays, MRIs and the like,-- is most naturally concentrated in the periphery of CCRCs, as are pharmacies, outpatient labs, doctors' offices. That's going to require a lot of parking space. It's a good thing this will take a couple of decades to happen; many mid-course adjustments will be imperative. But the basic fact is that the whole community's medical need is getting concentrated in CCRCs via Medicare, and so the community's facilities should move closer to that need. The younger community is well able to travel anywhere for elective medical services, especially when they move away. Makes a good chance to visit the grandparents while they are there, too.

All of these proposals depend on getting the attention and cooperation of other self-centered institutions: Medicare, hospitals, medical societies, municipal governments. The CCRC community has scant experience with asserting itself; its future will depend on how skillfully it begins to do so.

Nearly every retirement village has four or five retired physicians living in the place, as well as a dozen retired nurses, lab technicians, and others with medical experience. Every CCRC infirmary has four or five patients whose spouse is a resident of the community, visiting the infirmary regularly, and with sharpened insight. Some other people are natural leaders. If these people could be assembled into a permanent committee of medical oversight, charged with visiting other CCRCs in the region for ideas and perfecting the interface between the CCRC and nearby hospitals, medical facilities, transportation vendors, and politicians -- things would start to move. Spending twenty percent of our gross domestic product on health is, quite enough. Let's either stop spending so much or else make something good of it.

Reviving Schuylkill: Eight Miles From the Dam to Ft. Mifflin

|

| Joshua Nims |

Joshua Nims of the Schuylkill River Development Corporation recently addressed the Right Angle Club about current activities of that organization. It's a non-profit corporation, but in a sense is a quasi-City agency, spending State and Federal funds, plus remediation funds. Just what remediation funds are was not clearly explained, but seem to be fines or assessments on companies who are thought to have fouled up the environment. Whether those assessments are fair or unfair, too small or too large, are political issues largely avoided in Mr. Nims' presentation, and hence are avoided here.

|

| Gray's Ferry Bridge |

The Gray's Ferry area is certainly an urban tragedy of epic proportion, but since its deterioration began in 1856, the events of the Civil War probably had a lot to do with it. Up until the Civil War, the western banks of the Schuylkill, especially around Gray's Ferry, were famously upscale and beautiful. The South Street Bridge, for example, was originally envisioned as leading into a boulevard of the Arts, with the University Museum, Irvine Auditorium, the University Hospital and the mansions on the top of the hill setting off what promised to become a striking cultural statement. Anthony Drexel himself lived up there, walking it to work at Third and Chestnut. And that's just one famous example. It's hard to know what started the blight, but Harrison Brothers White Lead, Color and Chemical Works might be a good candidate and the fact that the area soon developed the tracks often (10) smoke-belching railroads was certainly another major issue. The western bank of the Schuylkill rose to a high rocky promontory at Gray's Ferry, crowding wartime industrialization into a narrow place. Before that, Gray's Ferry Bridge had been the main artery to the South, traveled by George Washington many times, often stopping at Woodlands, that palatial home of Andrew Hamilton the original Philadelphia lawyer. A century before that, the Dutch fur traders had found it to be the first firm land after they sailed inland through the swamp, while the Indians knew it was the last forest area before you reached the (South Philadelphia) area of malaria, yellow fever and other mysterious vapors that must be avoided. In the sense of land travel, Gray's Ferry was, therefore, the most prominent part of the Philadelphia landscape for two centuries. The ferry itself was a floating bridge, pulled back and forth by ropes on each shore of the river. Given a choice of pretty much all of the North American continent, John Bartram placed his farm just south of this promontory. Where it still stands today but surrounded by slums and urban decay.

It's a little hard to judge whether the Civil War pushed railroad construction into the only rocky crevice suitable, and then industrial pollution followed with vile and noxious effluents, or whether the Harrison Lead, Color, and Chemical factory simply started it across the river in the river bend. That's where the DuPont paint factory relocated in 1916, and in fact, the Duponts get local blame as polluters when in fact they made considerable effort to clean things up after they acquired it. The area had a major slaughterhouse abattoir, and an asphalt plant and several other major inducements to the populace to abandon their elegant mansions and run for their lives. The place now has old rusting bridges, tumble-down concrete pilings, lots of weeds, and not a single living fish for a century in that water. To diffuse the blame somewhat, it should be remembered that after the War of 1812, the Schuylkill was the main transportation artery for coal coming down from Pottsville and the rest of Schuylkill County. The river didn't have a sandy bottom, it was pulverized anthracite which releases acids and toxins when washed.

So that's the river region the Schuylkill Development Corporation plans to line with grassy running paths and benches to admire the view. Maybe the Wilson Steamship Line or something like it can again be persuaded to bring tourists here, or maybe the riverbanks can be lined with hotels to house people who take rides on river flatboats, as they do in San Antonio. Or dare we mention it, maybe Paris. Maybe Philadelphia can once again be a tax collector's idea of heaven, together with five-day weekends.

|

| Schuylkill River Development Corporation |

At the moment, this little non-profit city agency is run on a $500,000 operating budget, and has about $20 million worth of projects in progress. Some of that is reparation money pried from the grandchildren of the owners of those factories who did the damage over a century ago, and some large part of it is Philadelphia's share of the boodle from the Stimulus package. There's no doubt the area will look immensely improved in the next year or two, and a lot of hope that private investment will be attracted to an area previously shunned vigorously. The area which has already been cleaned up, from the Wissahickon to the Dam, really must be called a great success; there's lots of foot traffic and joyousness. And the area can also be praised in what unfortunately is the measurement of modern urban development: it has only had two lawsuits for sprained ankles, and only two muggings, quite a commendable record. But now development is going past South Street, into much murkier areas, with more low-income residential spaces. Surveillance cameras are planned, and bright lighting, but it's far from certain that a little strip of gentrification can defeat miles of surrounding decay.

Only if they pull it off will private investment creep into the area, and the parents of University students permit their children to run there. If private investment arrives, this organization can do no wrong, because only then can it fairly be described as "Infrastructure". My own definition of infrastructure as an economic stimulus is of early public spending on projects which would have eventually consumed the money anyway, except later. By that standard, infrastructure spending's only true cost would be the interest on borrowed money to do it sooner. Let's make a note to revisit this experiment in a couple of years, cautiously wishing everyone the best, in the meantime.

Revolt of the Pennsylvania Line

The Hudson Valley is not exactly within the bounds of Philadelphia culture and influence, those invisible geographical limits of this group of essays. The revolt of the starving, unpaid Revolutionary soldiers which took place there in 1780 was of tremendous importance to the formation of the nation but would be excluded from present consideration except for one thing. It was the Pennsylvania Line which led the revolt of the Continental Army.

Rise and Fall of Life Insurance

|

| Hammurabi Code |

While it is possible to see traces of the origin of insurance all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia, insurance of a currently recognizable form began around 1500, with maritime insurance creating risk pools for ships at sea. Eventually, insuring the life of a ship and ensuring the life of a person did not seem greatly different in principle; sooner or later everyone dies, but in those days sooner or later most ships sank. From the records of such pooling efforts, we can see that a sailor in colonial times had a 40% chance of not returning from a typical voyage. Learning this, some of the plots of Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice becomes more understandable, and the enormous wealth of successful sea captains, privateers, whalers and ship owners seems more justified by the risks they were taking. In retrospect, it seems hard to understand why anyone at all went to sea, thus why it took so long to discover America. Selling maritime insurance was a way to gamble on these risks. You might not get wet, but you were still taking big risks with your money.

Life insurance was a comparatively late arrival on the insurance scene and grew out of the experience with maritime risk pooling. The first life insurance company was the Presbyterian Ministers Fund, a Philadelphia institution if there ever was one. In essence, the church had undertaken to support the widows of ministers. Insurance tailored to the life of each minister, when pooled together, approximated the church's collective widow-support risk. Only ministers were insured by this fund, however. The Insurance Company of North America (now Cigna) seems to have been the first company to sell life insurance to all comers. That's definitely an improvement; limiting the risks to a particular occupation amounts to "adverse risk de-selection", unintentionally excluding, for example, women and blacks. On the other hand, the concept was totally new; no insurance at all would have been attempted if it had been initially impossible to limit the risk.

Insurance has since spread to many other topics, but it remains true that life insurance has one central unique feature. It is absolutely certain the customer will die, the policy will be cashed in. The uncertainty is when it will happen. After a while, it became evident that premiums would be collected until the final date, and could be invested until it happens. When the pool of customers gets large enough, there is almost perfect predictability about the average age at death, so the bigger the company the safer it should be.

There is one great potential weakness in this system, lying in the fact that the person who buys the policy and receives the assurances will not be around to complain about failures of those assurances at the time the policy is cashed in. It takes many years before public trust in such promises overcomes skepticism. The growth of life insurance was therefore slow until the Civil War suddenly demonstrated there were unpredictable risks around. Unfortunately, abuses of the system by fly-by-night companies in the last half of the Nineteenth Century led to heavy government regulation of the industry. Philadelphia's reputation for integrity rapidly expanded its dominance of insurance, but could not prevent the heavy hand of regulation from holding it down, or local taxes from driving it into other jurisdictions. State Insurance commissioners were originally charged with guarding against an insurance company going bankrupt by using unrealistic low prices to attract business. The public interest was redefined to mean low premiums, by the obscure but effective method of legally shifting the debts of a bankrupt insurer onto its surviving competitors -- neither the public nor the Legislature had to worry about it any further. In the insurance capital of the country, stockholder returns and executive salaries gradually went from too fat to too thin. Insurance companies, one by one, moved to other states or at least to other counties. It is now possible to wander through the abandoned executive suites on the top floors of the former insurance palaces and feel as though you were at Luxor, wandering through the abandoned Egyptian temples of Karnak.

To be fair about it, it is also possible to have a real estate agent take you through the former estates of life insurance entrepreneurs whose business practices amply justified some regulatory over-reaction. Plenty of old retired lawyers will be glad to tell you of the times they wrote new insurance laws for their insurance client, who just forwarded them to Harrisburg for enactment -- before the Second World War. But the destruction of this industry does no one any good, and it is surely fair to argue that excessive profits were the lesser of the two evils.

Setting the regulatory risk to one side, the life expectancy of Americans has dramatically lengthened in the past century, nearly eight years in the past fifty years. Such unpredictable reduction of risk ought to lead to increased profitability for the insurer, but it also leads the public to shift to less profitable term insurance. The young buyer can see a period of several decades of dependent children, followed by a long period of life when the death of the breadwinner is less tragic. I needed, living too long becomes a modern new concern, the outliving of accumulated savings. When the investment manager of the insurance e company is faced with a choice of more investment safety or greater investment return, he must produce a combination of both, an impossible assignment. And so, insurance business drops off as clients wander away toward more glowing promises, or at least toward promises unconstrained by the growls of a consumer-driven insurance commissioner. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, only two life insurance companies went bankrupt, so at least the old way of running these companies produced safety. The 1930s now seem a long time ago.

Rise of the Formidable State

Rittenhouse Square Area

|

| Rittenhouse Sq. |

The Rittenhouse Square "area" has far outgrown the square itself, and the term when used by locals usually refers to the whole area of central Philadelphia West of Broad Street to the Schuylkill, bounded roughly by Chestnut Street on the North, and Pine Street on the South. Rittenhouse Square Park is in the center of this primarily residential area and is now mostly ringed by apartment buildings. Rittenhouse Park was once enclosed by a high cast-iron fence with sharp-pointed palings and gates that could be locked at night, just like so many London Squares. The fence disappeared around 1900. Around 1840 the first house was built on the square, and then a fifty-year building boom (reflecting the burgeoning prosperity of the city) filled the fashionable area out to the limits defined by the Schuylkill bridges at South Street and Walnut or Chestnut Streets. Because of the advent of central heating and inexpensive window glass manufacture, the low ceilings and small windows to the East of Broad Street (promoted by the need for fireplace heat, plus laws taxing both windows and white paint) were replaced by tall ceilings and big windows without mullions. These townhouses were big, often with twenty or more rooms, and the occasional narrow streets filled with small houses were for servants, however, gentrified they may have recently become. The center of fashion shifted over the years, and right now probably Delancey Street is the pinnacle, although it is patchy and arguable. After the 1929 crash (of the stock market), many fashionable Families had to abandon the unmaintainable big house and move into the little servant house in the neighboring alley in order to remain in the fashionable area. The Big houses with its big taxes then became several apartments or a storefront with apartments above. Or it just deteriorated and then was torn down, unless some economic up swelling happened to rescue it again. The fact is that the number of big houses in the area exceeds the number of wealthy people who want to live in them, and the fashionable area has thus had to contract, but it has not disappeared, either.

|

| Spruce Street |

Rather than swamp this blog with a tedious recital of the previous occupants of so many show houses, let it suffices to say that the families which once had the most Notable Houses around and near Rittenhouse Square were Roberts, Weightman, Frazier, Gibbs, Harrison, Stotesbury, Cassatt, Jayne, Harding, Janney, Gazzam, Scott, Dobbins, Bullitt, Baugh -- and, of course, many others too.

Within this district, churches abound at the Northwest corner. Clubs are strung along the Eastern border, between the residences and the financial district along Broad Street. And the Southern border is where the doctors used to be. I had an office once at 19th and the Square, but the main concentration of doctors was on Spruce Street. If you have seen Harley Street in London, you will recognize the pattern. Originally, the doctor had his office on the ground floor and lived upstairs. The zoning regulations in both London and Philadelphia permitted professional use of the first floor only if the professional lived in the house. So, when the advent of automobiles induced most doctors to live in the suburbs, the office continued on the first floor of these houses, and the doctor's nurse lived upstairs, to satisfy the requirement of the zoning law. But that was just a transient phase; the advent of health insurance during World War II induced a more hospital-centered medical practice, and Spruce Street soon lost its medical flavor as doctors concentrated their offices around hospitals and their ample parking lots.

|

| Resselaer |

As traffic heading for the South Street bridge or the Walnut-Chestnut-Market bridges defines the limits of the district, the Rittenhouse Area has more or less contracted to the four blocks of East-West streets which terminate at the river, creating a more quiet and peaceful cul-de-sac.

Some idea of the former grandeur of the area can be gained by looking at the former Van Rensselaer home at 18th and Walnut, which had a brief fling as a private club before it became a gift shop. Or the Wetherill Mansion further South on 18th Street which now houses the art alliance. Or the grey stone house a couple of doors to the West of it which was where Governor Earle lived and was the last single-family house on the square. One of the houses on DeLancey Street was featured in the movie "Trading Places" as Hollywood's idea of real opulence, and a great many other houses tell a famous story. The Rosenbach Museum is at Spruce Street, very well worth a visit, particularly on Bloomsday. And the Thaw House at 1710 Spruce tells a particularly lurid tale of the Gilded Age.

12 Blogs

Easter Sunrise in Philadelphia

William Penn laid Philadelphia out in squares, using a compass for North. If he had used true North instead of magnetic North, Easter sunrise might shine down every cross street just in time for an awesome spectacle.

William Penn laid Philadelphia out in squares, using a compass for North. If he had used true North instead of magnetic North, Easter sunrise might shine down every cross street just in time for an awesome spectacle.

New Castle, Delaware

A short history of a historically significant town, now off the beaten path.

A short history of a historically significant town, now off the beaten path.

The Houses in the Park

William Penn intended his city to stretch from river to river, with the gentry living in mansions along the Schuylkill. Briefly, it was so; the mansions are on display in Fairmount Park.

William Penn intended his city to stretch from river to river, with the gentry living in mansions along the Schuylkill. Briefly, it was so; the mansions are on display in Fairmount Park.

Delaware's Court of Chancery

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's where the major corporations of the nation plead their case.

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's where the major corporations of the nation plead their case.

Riverline: Camden and Amboy Revival

One of the oldest rail lines in America is coming back to life, and maybe bringing the towns along with it back to life, too.

One of the oldest rail lines in America is coming back to life, and maybe bringing the towns along with it back to life, too.

Rail Station at Broad and Washington

Retirement Communities (CCRC)

Retirement communities of the continuing-care variety, are a comparatively new and apparently splendid development. The present economic crisis is their first major test.

Retirement communities of the continuing-care variety, are a comparatively new and apparently splendid development. The present economic crisis is their first major test.

Reviving Schuylkill: Eight Miles From the Dam to Ft. Mifflin

Cleaning up eight miles of banks of the Schuylkill from Fairmount Dam to Fort Mifflin, is Philadelphia's share of the Obama Stimulus Package. It will take a decade to know whether it was worth it, but as the program begins, it stirs a lot of excitement.

Cleaning up eight miles of banks of the Schuylkill from Fairmount Dam to Fort Mifflin, is Philadelphia's share of the Obama Stimulus Package. It will take a decade to know whether it was worth it, but as the program begins, it stirs a lot of excitement.

Revolt of the Pennsylvania Line

After Yorktown, the American revolution seemed over, but peace negotiations dragged on, probably intentionally. The troops wanted to go home so badly they nearly lost the victory.

Rise and Fall of Life Insurance

Like many things, insurance started here. It's now mostly all gone.

Like many things, insurance started here. It's now mostly all gone.

Rise of the Formidable State

The Catholic Church came to dominate Europe and its monarchs. Over a period of 300 years, secular governments became steadily more powerful. In 1648, the so-called Peace of Westphalia established that henceforth Kings would dominate churches. The American Constitution stabilized this upheaval for America in 1787, in its present uniquely American form.

Rittenhouse Square Area

This was the heart of uppercrust society during the Gilded Age.

This was the heart of uppercrust society during the Gilded Age.