9 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Religion

New volume 2012-07-04 13:22:31 description

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

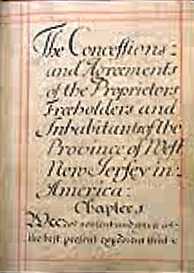

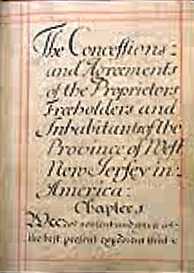

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

The Society of Friends

New volume 2019-05-23 17:20:54 description

Quakers: The Society of Friends

According to an old Quaker joke, the Holy Trinity consists of the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Quakers, or the Society of Friends, originated as a dissenting religion during the Sixteenth Century. George Fox founded the religion in the region near Manchester, England. Interestingly, the Industrial Revolution began in the same place, at about the same time or only slightly later. Quakerism borrowed some features of German Mennonites, particularly pacifism and simplicity of speech and dress. Quietism, with totally silent meetings as a religious experience, may have been centuries older in monasteries, but it is fair to surmise that it came to the Quakers from the Mennonites. It is still common to hear Mennonites referred to as German Quakers. Fox was an evangelist among the poorly educated classes of society, many of them made newly-aware of their own ideas by translations of the Bible. A handful of well-educated and well-born converts to the religion, led by William Penn, wrote down, softened, and intellectually strengthened the ideas of the quietist movement into a simpler but coherent and sophisticated body of thought. Less is more.

A good example of the simplifying process at work is the name of the religion. Originally, the group were "Friends of the Truth", with dissent thus strongly implied. To become The Society of Friends is a quite another thing, but the evolution was too slow and subtle to provoke resistance.

In fact, it is now difficult to identify anything other than War that Quakers uniformly and strongly oppose. By extension, violence and the incitement to violence, intemperate language or confrontation are deplored, although not cursed as sins. Outsiders unfamiliar with the group sometimes mistake mildness for timidness, and are soon taught a lesson in what is called "steely meekness". The group began with dissent from chivalry, feudalism, and class domination; it resisted the expensive and superficial religious forms of music, ritual, architecture, ceremony, and dress. But as society has itself moved away from such things, Quakers no longer think it is important to advertise their beliefs by adopting "plain" dress and speech or even making a useless fuss about courtroom oaths and pledges. But it is probably true that art, music and everyday dress in Philadelphia is a little less ornate than it might have been without early Quaker disapproval.

In the past century, with the single exception of anti-war conscientious objection, Quaker beliefs have all moved in a positive direction. Steely meekness has shifted from protesting the abuse of Native Indian Tribes, to the posture of assisting the victims of this or any other bigoted oppression. Or natural disaster, of course, but the victims of wars and oppression most readily evoke action and service on their behalf. When such relief is temporarily unpopular, the need for private assistance seems greatest, since government relief is constrained. Prison relief is in this class, both because it leans against the instincts of government, and because Quakers have ample cause to remember the experiences of their own conscientious objectors.

Quakers have continued to evolve since the death of William Penn. Plain speech and plain living quietly continue, but have moved away from the "ostentation of quaintness". Two presidents of the United States have been Quakers, several have won Nobel Prizes, and this group of about twenty-five thousand continues to exert a disproportionate leadership in the nation. Anyone may ask to join the religion, but no one is ever solicited to do so.

In this collection of essays about Philadelphia, we concentrate mostly on the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. It is important to understand, however, that there are 30,000 Quaker members of over a thousand monthly meetings in Bolivia and Peru; the largest yearly meeting in the world is in Africa, the Kenya Yearly Meeting. In the United States, there are today 33 yearly meetings, of which the Philadelphia one is the largest, with 11,000 members. It contains 103 constituent or "monthly" meetings, scattered from Barnegat, New Jersey to Center County, Pennsylvania, and on a north-south axis from upstate New York to the eastern shore of Maryland. It, therefore, covers the area originally owned by William Penn, the so-called "Quaker Colonies". Some evangelical yearly meetings resemble Protestant denominations, with ministers, hymns, and collection plates. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting remains "unprogrammed", adhering more strictly to the traditions of silent worship in its weekly meetings for worship, although the monthly meetings for business while orderly are anything but silent. Collections of two to ten monthly meetings will assemble every three months for "Quarterly Meeting", which is usually organized with an agenda. To hold this unstaffed archipelago of adherents together, the Yearly Meeting itself does have a full-time staff with a budget of over $5 million a year and conducts an annual program of business and discussion lasting several days. Among the various projects under its care is the supervision of 55 local private Quaker schools. Adding the informal but strong relationship with three outstanding colleges and a half-dozen retirement villages, the influence of these 11,000 members requires more active individual participation than is seen in most other religions.

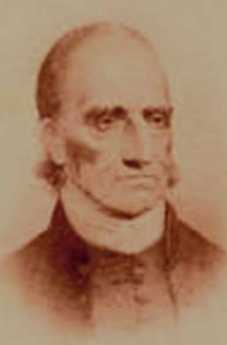

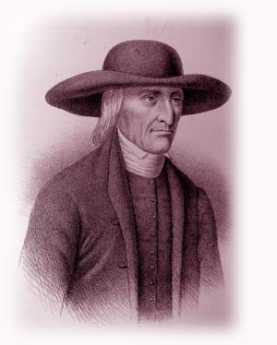

Henry Cadbury Dresses Up for the King

|

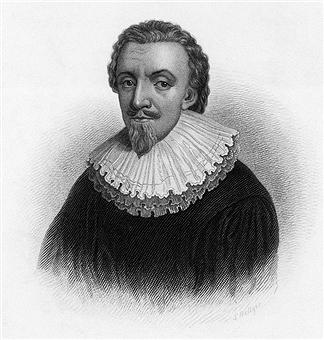

| Henry Cadbury |

There are a few old Quaker Clothes in the attics of their descendants, and on suitable occasions, an old broad-brimmed hat or two will appear at a Quaker gathering, for amusement. Quakers gave up the old style of "plain dress" when it became generally agreed that such eccentric dress was not plain at all but rather drew attention to itself. On the other hand, there is a distinctly unfashionable quality to almost everything Quakers do wear. When silk and nylon stockings were fashionable for women, Quaker women often wore black stockings. When it became the style for women to sport black stockings, Quaker women usually wore flesh-colored nylons. Among men, thin metal-trimmed spectacles displayed the same counter-fashionable tendency. Nowadays, these little quirks are often public signals among strangers, a way of wig-wagging "I notice you are a Quaker, so am I." And of course, unfashionable clothes are cheaper, and that's always a good thing.

And so it happened in 1947 that the Quakers were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, with information passed along that white tie and tails were the expected form of dress at the ceremony. Henry Cadbury was selected to receive the award on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, and you can be sure Henry Cadbury didn't own a set of tails. Henry was also very certain he wasn't going to go out and buy a set, just for a single wearing.

The AFSC collects used clothing, to distribute to the poor. Henry inquired whether there might be a set of white tie and tails to be found in the used-clothing bin, and luckily there was. It had been collected on behalf of the Budapest Symphony Orchestra when that impoverished but distinguished group of musicians was invited to give a concert in London. One of the monkey suits more, or less, fit Henry.

So, after investing in dry cleaning and pressing, Henry packed it up and went off to Oslo, to meet the King.

Slavery: If This be done well, What is done evil?

|

| Francis Daniel Pastorius |

The Declaration of the German Friends of Germantown, Against Slavery, in 1688.

These are the reasons why we are against the traffic of men's body, as followeth:

Is there any that would be done or handled in this manner? viz.: to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? How fearful and faint-hearted are many at sea, when they see a stranger vessel, being afraid it should be a Turk, and they should be taken, and sold for slaves in Turkey. Now, what is this better done, than Turks do? Yea, rather it is worse for them, which say they are Christians; for we hear that the most part of such negers is brought hither against their will and consent and that many of them are stolen. Now though they are black, we cannot conceive there is more liberty to have them, slaves, as [than] it is to have other white ones. There is a saying , that we shall do to all men like as we will be done [to] ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent, or color they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, which is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of the body, except evil-doers, which is another case. But to bring men hither, or to rob, [steal] and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe, there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed which are of black color. And we who know others, separating wives from their husbands, and giving them to others: and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! do consider well this thing, you who do it, if you would be done in this manner--and if it is done according to Christianity! You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe when they hear of [it,] that the Quakers do here handler men as they handle there the cattle. And for that reason, some have no mind or inclination to come hither. And who shall maintain this your cause, or plead for it? Truly, we cannot do so, except you shall inform us better hereof, viz,: That Christians have liberty to practice these things, Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse, towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating husbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at, [by]; therefore, we contradict [oppose], and are against this traffic of men's body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid purchasing such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing, if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of the hands of the robbers, and set free as in Europe. Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead, it hath now a bad one, for this sake, in other countries. Especially whereas the Europeans are desirous to know in what manner the Quakers do rule in their province; and most of them do look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil?

If once these slaves ( which they say are so wicked and stubborn men,) should join themselves--fight for their freedom, and handle their masters and mistresses, as they did handle them before; will these masters and mistresses take the sword at hand and war against these poor slaves, like, as we are able to believe, some will not refuse to do? Or, have these poor negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?

Now consider well this thing, if it is good or bad. And in case you find it to be good to handle these blacks in that manner, we desire and require you hereby lovingly, that may inform us herein, which at this time never was done, viz., that Christians have such a liberty to do so. To this end, we shall be satisfied on this point, and satisfy likewise our good friends and acquaintances in our native country, to whom it is a terror, or fearful thing, that men should be handled so in Pennsylvania.

This is from our meeting at Germantown, held ye 18th of the 2nd month, 1668, to be delivered to the monthly meeting at Richard Worrell's.

Garret Henderich

Derick op de Graeff

Francis Daniel Pastorius

Abram op de Graeff.***

At our Monthly meeting, at Dublin, ye 30th 2d mo., 1688, we have inspected ye matter, above mentioned, and considered of it, we find it so weighty that we think it not expedient for us to meddle with it here, but do rather commit it to ye consideration of ye quarterly meeting; ye tenor of it is related to ye truth.On behalf of ye monthly meeting,

Jo. Hart.

***

This above mentioned was read in our quarterly meeting, at Philadelphia, the 4th of ye 4th mo., '88, and was from thence recommended to the yearly meeting, and the above said Derick, and the other two mentioned therein, to present the same to ye above said meetings, it is a thing of too great a weight for this meeting to determine.Signed by order of ye meeting.

Anthony Morris

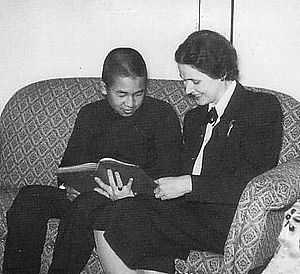

International Visitors Council

|

| Nancy Gilboy |

The President of IVC, Nancy Gilboy, tells us it stands for International Visitors Council, now approaching its 50th anniversary. As you might suppose, it is located at 1515 Arch Street, near the old visitors center. Philadelphia has a new visitors center on 5th Street, of course, and perhaps it takes time to move or maybe moving isn't in the cards. We had another Visitors center on 3rd Street that came and went, so proximity between Center and Council perhaps isn't as important as rental costs, or leases, or other issues.

|

| Philadelphia Art Museum |

The Council has a modest budget, but a great idea. Anyone who has traveled much knows that you tend to follow the travel agent's set agenda for a town, you see a lot of churches and museums, but you can almost never get tickets for the local entertainment events, and you almost never meet any local people except taxi drivers and bellhops. That's even more true of young travelers, who don't have either the money or the experience to anticipate the issue, or enough local friends to guide them around the obstacles (This exhibit closed on Mondays, that event is all sold out, this event was spectacular, you should have been there yesterday, sorry we didn't know you were coming we have a wedding to go to, etc.). On guided tours, it is remarkable how few things seem to happen after 4 PM.

So, fifty years ago, some imaginative Philadelphia leaders got the idea that a lot of Philadelphia residents would enjoy taking some foreign tourists under their wing, maybe have somebody to know when they, in turn, make a reciprocal visit, maybe boast about our town a little. Furthermore, by getting involved with the US State Department, young visitors can be identified as potential future leaders in their country. If the guess is a good one, and the experience favorable, Philadelphia might prosper from the publicity and from the later return visits, now in the triumph of success. That was the founding spirit of the Philadelphia International Visitors Council.

So that's how it came about that Margaret Thatcher, < Tony Blair, the current President of Poland, and the head of the Russian Space Program were once visitors in Philadelphia homes. People who like to do this sort of thing tend to like each other, so the monthly receptions (First Wednesday at the Warwick) are interesting Philadelphia social occasions in their own right. Success begets success, and the CCP (originally Business for Russia) has affiliated itself, along with the Philadelphia Sister Cities Program, the Consular Corps Association, The Philadelphia Trade Association, and probably others.

Look at it from the visitors' viewpoint. New York has larger colonies of foreign nationals than Philadelphia does, but New York is an expensive place to visit. Washington has dozens and dozens of embassies, but a visitor soon learns the last thing an embassy staff wants to see, is a citizen from home. So those places aren't really a typically American place to visit. Indiana is plenty American, but there isn't much to see there. So Philadelphia has many attractions, lots of history, it's as thoroughly American as a city can be, and all it needs is someone to open up and show it to you. Cleverly organized, the IVC has undoubtedly put the Philadelphia stamp on many foreign visitors, without their exactly recognizing they are being told This is America. If the State Department is shrewd in its assessment process, Philadelphia will in time be held in high esteem by the leaders of a lot of foreign nations.

In the spirit of announcing that Philadelphia is where you can find America, my own little daughter astonished me at a dinner party by telling the assembly the following story:" William Penn was nice to the Indians, so it was safe to land in Philadelphia. Pretty soon, so many people landed here they had to move West to settle down. And, folks, that's why the people to the North of us talk funny, and the people to the South of us talk funny -- but everybody else in America talks like Philadelphia!"

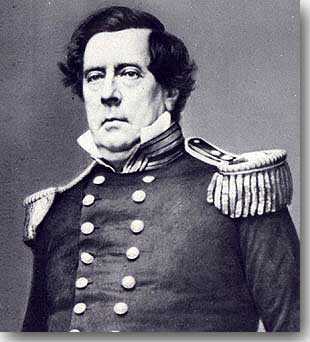

John Woolman Reports on Yearly Meeting, 1758

|

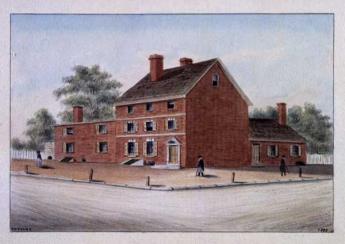

| John Woolman House |

"In this yearly-meeting (1758) several weighty matters were considered; and, toward the last, that in relation to dealing with persons who purchase slaves. . . .

"Many faithful brethren labored with great firmness, and the love of truth, in a good degree, prevailed. Several Friends who had Negro's expressed their desire that a rule might be made to deal with such Friends as offenders who bought slaves in future. To this, it was answered, that the root of this evil would never be effectually struck at until a thorough search was made into the circumstances of such Friends who kept Negro's, with respect to the righteousness of their motives in keeping them, that impartial justice might be administered throughout. Several Friends expressed their desire that a visit might be made to such Friends who kept slaves, and many Friends said that they believed liberty was the Negro's' right; to which, at length, no opposition was made publicly. A minute was made, more full on that subject than any heretofore, and the names of several Friends entered, who were free to join in a visit to such who kept slaves. "

Jury Nullification

|

| Tom Monteverde |

We must be grateful to the late distinguished litigator, Tom Monteverde, for reminding us of the importance of the jury in American history. Juries seldom realize how much power they can have if they unite on a common purpose. In fact, juries have the implicit right to veto almost anything the rest of government does, by rendering it unenforceable. If the jury opinion is a majority view, nothing but a civil war can legally stop them. So it helped Washington to have jury nullification seem an invincible Quaker idea, while the South trusted a rich slave-owner who had renounced power.

|

| William Penn |

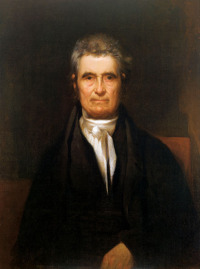

The right to a jury trial originated in the Magna Carta in 1215, but a jury's essentially unlimited power was established four centuries later by Quakers. The legal revolution grew out of the 1670 Hay-market case, where the defendant was William Penn, himself. Penn was accused of the awesome crime of preaching Quakerism to an unlawful assembly, and while he freely admitted his guilt he challenged the righteousness of such a law. The jury refused to convict him. The judge thus faced a defendant who said he was guilty and a jury who said he wasn't. So, the exasperated judge responded -- by putting the jury in jail without food.

The juror Edward Bushell appealed to the Court of Common Pleas, where the problem took on a new dimension. The Justices certainly didn't want juries flouting the law, but nevertheless couldn't condone a jury being punished for its verdict. Chief Justice Vaughn decided that intimidating a jury was worse than extending its powers, so the verdict of Not Guilty was upheld, and Penn was set free. Essentially, Vaughn agreed that any jury that wasn't allowed to acquit was not really a jury. In this way, the legal principle of Jury Nullification of a Law was created. A verdict of not guilty couldn't make William Penn innocent, because he pleaded guilty. A verdict of not guilty, under these circumstances, meant the law had been rejected. Jury nullification thus got to be part of English Common Law, hence ultimately part of the American judicial system.

|

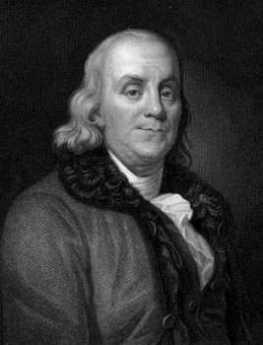

| Andrew Hamilton |

This piece of common law was a pointed restatement of just who was entitled to make laws in a nation, whether or not nominally it was ruled by a king or a congress. Repeated British evasion of the principles of jury trial became an important reason the American colonists eventually went to war for independence, and probably a better one than some others. The 1735 trial of Peter Zenger was an instance where Andrew Hamilton, the original "Philadelphia Lawyer", convinced a jury that British law, blocking newspapers from criticizing public officials for improper conduct, was too outrageous to deserve enforcement in their court. In that case, jury defiance became even more likely when the judge instructed the annoyed jury that "the truth is no defense". Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette was here quick to come to the side of jury nullification, saying, "If it is not the law, it ought to be law, and will always be law wherever justice prevails." Franklin quickly became allied with Andrew Hamilton, who became Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly.

|

| John Hancock |

The Zenger case was often stated to be the origin of the Freedom of the Press in our Constitution fifty years later, but in fact the First Amendment merely provides that Congress shall pass no laws like that. Hamilton had persuaded the Zenger jury they already had the power to stop enforcement of such tyranny, and the First Amendment could be seen as trying to prevent enactment of laws that will foreseeably incite a jury to revolt.

The Navigation Acts of the British government, for example, were predictably offensive to the American colonists, whose randomly chosen representatives on juries were then rendered useless with their wide-spread refusal to convict. This, in turn, provoked the British ministry. John Adams made a particularly famous defense of John Hancock who was being punished with confiscation of his ship and a fine of triple the cargo's value. Adams was later singled out as the only named American rebel the British refused to exempt from hanging if they caught him. As everyone knows, Hancock was the first to step up and sign the Declaration of Independence, because by 1776 there was widespread colonial outrage over the British strategy of transferring cases to the (non-jury) Admiralty Court. Many colonists who privately regarded Hancock as a smuggler were roused to rebellion by the British government thus denying a defendant his right to a jury trial, especially by a jury almost certain not to convict him. To taxation without representation was added the obscenity of enforcement without due process. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the newly created United States, ruled in 1794 that "The Jury has the right to determine the law as well as the facts." And Thomas Jefferson built a whole political party on the right of common people to overturn their government, somewhat softening, it is true, when he grasped where the French Revolution was heading. Jury Nullification then lay fairly dormant for fifty years. But since the founding of the Republic and the reputation of many of the most prominent founders was based on it, there was scarcely need for any emphasis.

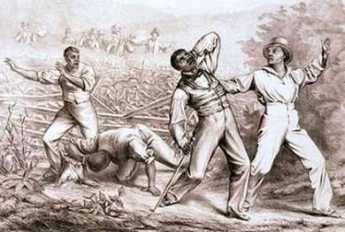

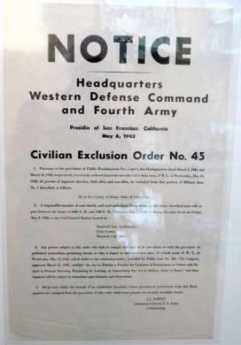

|

| Slave |

And then, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 began to sink in. It became evident that juries in the Northern states would routinely refuse to convict anyone under that law, or under the Dred Scott decision, or any other similar mandate of any branch of government. In effect, Northern juries threw down the gauntlet that if you wanted to preserve the right of trial by jury, you had better stop prosecuting those who flouted the Fugitive Slave law. In even broader terms, if you want to preserve a national government, you had better be cautious about strong-arming any impassioned local consensus. A rough translation of that in detail was that no filibuster, no log-rolling, no compromises, no oratory, no threats or other maneuvers in Congress were going to compel Northern juries to enforce slavery within their boundaries of control. All statutes lose some of their majesties when the congressional voting process is intensely examined, and public scrutiny of this law's passage had been particularly searching. Even if Southern congressmen would be successful in passing such laws, it wasn't going to have any effect around here. The leaders of Southern states quickly got a related message, and their own translation of it was, "We have got to declare our independence from this system of government that won't enforce its own laws". If juries can nullify, then states can nullify, and the national union was coming to an end. Both sides disagreed so strongly on this one issue they were willing, for the second time, to risk war for it.

Ku Klux Klan

The idea should be resisted that Jury Nullification is always a good thing. After the Civil War, many of the activities of the Ku Klux Klan were tolerated by sympathetic juries. Many lynch mobs of the Wild, Wild West were encouraged in the name of law and order. Prohibition of alcohol by the Volstead Act was imposed on one part of society by another, and Jury Nullification effectively endorsed rum-running, racketeering, and organized crime. The use of marijuana and abortion are two further examples where disagreement is so strong that compromise eludes us. What is at stake here is protecting the rights of a minority, within a society run by a majority. If minority belief is strong enough, jury nullification issues an unmistakable proclamation: "To proceed farther, means War."

|

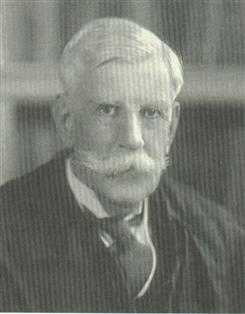

| Oliver Wendell Holmes |

That's a somewhat strange outcome for a process started by pacifist Quakers, so the search goes on for a better idea. Distinguished jurists differ on whether to leave things as they are. In a famous exchange, Oliver Wendell Holmes once had dinner with Judge Learned Hand, who on parting extended a lawyer jocularity, "Do justice, Sir, do justice." To which, Holmes then made the somewhat surly response, "That is not my job. My job is to apply the law."

Thus lacking any better approach, it is hard to blame the US Supreme Court for deciding this was something best left unmentioned any more than absolutely necessary. The signal which Justice Harlan gave in the majority opinion on the 1895 Sparf case was the very narrow ruling that a case may not be appealed, solely on the basis that the trial jury was not informed of its right to nullify the law in question. Encouraged by this vague hint, what has evolved has been a growing requirement that incoming jurors take an oath "to uphold the law", officers of the court (ie lawyers)are discouraged from informing a jury of its true power to nullify laws, and Judges are required to inform the jury in their charge that they are to "take the law as the judge lays it down" (ie leave appeals to higher courts). If a jury feels so strongly that it then persists in spite of those restraints, well, you apparently can't stop them. Nobody thinks this is a perfect solution, and aggrieved defendants like the Vietnam War protesters are quite vocal in their belief that the U.S. Supreme Court finally emerged with a visibly asinine principle: a jury does indeed have the right to nullify, but only as long as that jury is unaware it has that right. That's almost an open invitation to perjury if accurate; but while it's not precisely accurate, it comes close to being substantially true.

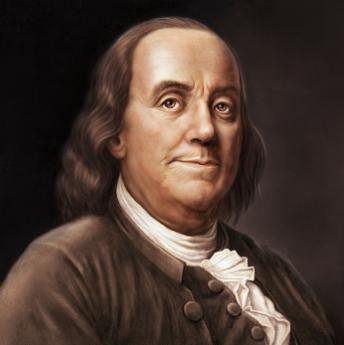

That's where matters stand, and apparently will stand, until someone finds better arguments than those of Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Andrew Hamilton -- and William Penn.

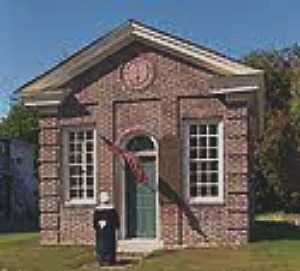

North of Market

|

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

In their 1956 book "Philadelphia Scapple", Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Mrs. Henry Cadwalader give an interesting description of the evolution of the term "North of Market". In the early days of the city, almost all of the town was South of Market Street. In fact, an early 18th Century visitor once wrote that he always brought a fowling piece when he visited Philadelphia because the duck hunting was so good at the pond located at what is now 5th and Market.

When the Quaker meeting house was built at 4th and Arch Streets, many of the more important Quaker families thought it was important to build their houses nearby. In that way, Arch Street developed the reputation of being a Quaker Street. So the original meaning of the North of Market term was the Quaker ghetto. Quaker families continued to spread West along Arch Street or nearby, and this accounts for the location of the Friends Center at 15th and Cherry and related local activities. When the Free Quaker were evicted from the meeting at 4th and Arch because of their activities during the Revolution, they built their own meeting at -- 5th and Arch.

|

| Chinese wall |

During the Civil War, a number of people made fortunes that socially upscale people over in the Rittenhouse Square area considered disreputable, so elaborate but ostracized mansions marched due North up Broad Street, where they can still be observed as stranded whales in the slums, leaders without followers. The show houses of manufacturers of shoddy war goods soon gave the meaning of parvenu to the term North of Market.

And then, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran an elevated brick structure from 30th Street to City Hall Plaza, the so-called Chinese Wall. For nearly a century this ugly looming structure on Pennsylvania Boulevard, now John Kennedy Boulevard, with its smoky engines above, and dark dripping tunnels at street level, sliced the town in half and made it very unattractive to build or to live, North of Market. The Spring Garden area had some pretty large and expensive houses, but it was cut off by the railroad trestle and has only recently started to revive. It helped a lot to tear down the Chinese Wall, but that was fifty years ago, and the area has taken a long time to recover from the earlier diversion of social flow to the South of it. And, psychologically, North of Market will take even longer to recover from the implication of -- industrial slum.

|

| center |

Meanwhile, of course, Oriental immigration settled along Arch Street at 9th to 12th Streets, and we now have our Chinatown there, complete with street signs in oriental lettering. In effect, we have a real Chinese Wall, a social one. Just what will happen to this group is unclear, since it is readily observable that they like to cluster together, unlike the East Indian immigrants, who head for the suburbs as fast as they can. Since the Chinese colony is physically blocked on all sides by the Vine Street Expressway, the Convention Center, and the Ben Franklin Bridge, it is hard to know where they will flow if the group gets much larger. The depressed Vine Street crosstown expressway makes a definitive border for downtown, and the contrast between the two sides of this expressway is striking. On one side is Camelot, and on the other side, almost nothing is being built. The future of North of Market, at the moment, is a little unclear.

Pennyslvania's Boundary: David Rittenhouse, Hero, Lord Baltimore, Villain

|

| David Rittenhouse |

In the Twenty-first Century, when we know how every American creek and river run, we can see it might have been simple to establish a boundary between the new royal grant to William Penn, and an earlier grant to Lord Baltimore by the then-reigning king's father, Charles I. Essentially: Penn got the Delaware Bay and a lot of wilderness to the west of it. George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had long held the top half of the Chesapeake Bay and a strip of wilderness to the west of that. Two bays, with two hazy strips of wilderness attached.

|

| George Calvert, Lord Baltimore |

At what is now Odessa, Delaware, those two bays are only five miles apart; compromise should have settled the issue quickly. Two English gentlemen could have sat down over a pipe and a brew, working something out. However, the English nation was then changing kings, beheading them over matters of religion. A Roman Catholic, Lord Baltimore probably thought an opportunity might emerge from the turmoil if he stalled until matters went his way, since next in line of succession was James, Duke of York, who was a Catholic. But matters fall into the hands of the lawyers when principals of an argument are unable to speak. As we noted elsewhere, in the legal system of the day the last word from the last king was what counted in law courts, accepting any uncertainty about future latest words from future latest kings in order to maintain immediate peace. To lawyers of the time, all this talk about justice, fairness, and geometry was idleness when the nation needed order and stability. So the Calvert family lawyers over the course of eighty years, introduced one specious proposition after another that turned other lawyers purple with rage. Penn's lawyer, Benjamin Chew, beat them at this game, and his mansions in Delaware and Germantown attest to the value attached to this achievement. In other circumstances, posturing might have led to war, as it did in similar disputes with Connecticut. Penn probably knew better, but it takes two to compromise.

|

| Mason-Dixon Line |

It must be admitted that honest confusion was possible. Sometimes, a line of latitude was a line in the sense Euclid intended: all length and no width. At other times, lawyers and kings were talking about "parallels" as if they were strips, roughly sixty miles wide. If a sixty-mile strip was intended, it was important for a grant to specify whether it extended to the southern edge of the strip, or to the northern edge. But in fact, the state of science in the Seventeenth Century contained uncertainty about both where the strips were, and how wide. And if the grant's language didn't even make it clear whether the parties were talking about strips or width-less lines, eighty years could be a comparatively short time for a court to decide the case. To be fair to Lord Baltimore, many people at the time didn't think these matters were capable of fair solution, so the traditional way of dealing with land disputes was either by force or by craftiness.

|

| David Rittenhouse Birth Place |

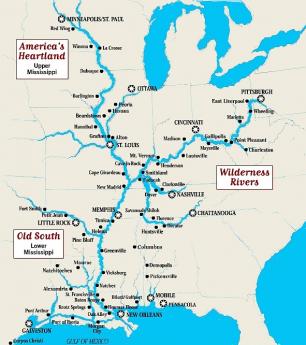

In William Penn the folks from Maryland were, unfortunately, dealing with a friend of the King, who had one of the most brilliant mathematicians in Western civilization as his adviser. David Rittenhouse may have been born in that little farmhouse you can still visit on the Wissahickon Creek, and made his living as a clockmaker, but his native talents in mathematics, astronomy surveying, and instrument construction were so deep and so varied that later biographers are reduced to describing him merely as a "scientist" and letting it go at that. If you want to sample his talents, spend an hour or two learning what a vernier is, and then see if you could apply that insight, as he did, to a compass. So, as it turned out, Rittenhouse was able to describe a twelve-mile circle around New Castle, Delaware, construct a tangent that divides the Delmarva's Peninsula in half, and match it up with an east-west line we now call the Mason Dixon Line. When they finally got around to laying these lines on the ground, Mason and Dixon cut a twenty-four-foot swath through the forest, using astronomical adjustments every night, and laying carved marker stones every fifth of a mile for hundreds of miles. The variation from the line devised by Rittenhouse was at most a fifth of a mile off the mark; the intersection with the north-south line between Maryland and Delaware was less successful. The survey by Mason and Dixon was not quite completed to the Ohio line because the Indians, curious at first, eventually became wild with suspicion at such behavior, particularly the part about going out and aiming cannons at the sky every night. It seems likely that George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had no more confidence in this madness than the Indians did.

So, the next time you take the train from Philadelphia to Washington DC, reflect that strict reading of the words in the land grants did admit the possibility that your whole trip could either have been within the State of Maryland, or else in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, depending on whether lawyers, or scientists, had triumphed in this dispute. Since the Mason Dixon Line later divided not merely two states, but two violently opposed cultures, Rittenhouse must stand out in the history of one of those people who were so smart that most people couldn't understand how smart he was.

Edward Hicks: Peaceable Kingdoms

|

| Peaceable Kingdoms |

Edward Hicks (1780-1849), the most important folk artist of American art, was born and lived all his life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. About a hundred of his paintings survive, 62 of which are versions of "The Peaceable Kingdom". Recently, his Peaceable Kingdoms have been selling for more than $4 million apiece, and the other works at more than a million. As is so often the case, he was born in poverty and spent his life in poverty, so the financial benefits have all gone to middle-men.

Hicks had to overcome an additional handicap. Quakers disapproved of painting things up just for show, and they strongly disapproved of the vanity underlying the act of having a portrait painted of yourself. In fact, the early Quakers would not even permit their names to be placed on their tombstones.

Hicks was apprenticed into the wagon business and showed a talent for painting them. From that, entirely self-taught, he migrated into the business of painting business signs in an age of limited literacy. The Blue Anchor Tavern, the King of Prussia Inn, the Crossed Keys Tavern and the signs of various tradesmen were an essential part of conducting business. It is easy to see these tradesmen signs in the easel paintings of Hicks' later career, which reduce themselves to rearrangements of such individual sign paintings to make a coherent canvas.

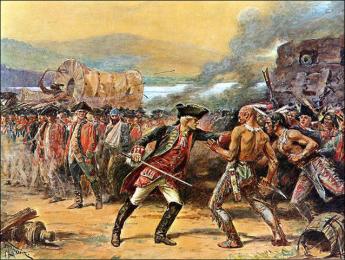

If you have seen one "Peaceable Kingdom" you haven't seen them all, but you only need to see one to be able to recognize the others at sight. They generally form a group of wild animals and an occasional child in the right foreground, with a grouping of Quakers and Indians in the left background, taken from Benjamin West's famous portrayal of Penn signing the treaty of peace with the Delaware Indians. The scene is taken from Chapter 11 of Isaiah, in which the lion lies down with the lamb.

Hicks was not a successful farmer, and he had to overcome Quaker resistance even to sell religious paintings with a Quaker moral. No doubt the resistance was strengthened by the fact that his cousin Elias Hicks had split the Quaker church into two (Conservatives and Hicksites) in 1827, and Edward was himself a strong itinerant preacher. Although the plain message of the Peaceable Kingdom is reconciliation between the two branches of Quakerism, he probably encountered a fair amount of coolness among the Conservative opposition.

Hicks was neither an educated nor a sophisticated man. It is forgivable that he made such a strong Old Testament statement when he and his cousin represented a dissenting sect that was gravely doubtful about the wisdom of allowing your life to be ruled by biblical verses.

Quaker Investment Committee

|

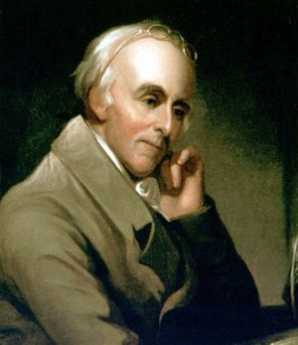

| Jonathan Rhoads |

Charitable institutions and other non-profit organizations occasionally assemble an endowment and thus develop a need for an oversight committee to hire (and occasionally fire) an investment manager, to monitor the fund's management, and to assess the manager's fees. The meetings of the oversight committee could, therefore, be pretty brief, related to two numbers. How had the endowment portfolio performed, compared with some acknowledged benchmark? To these two numbers might be added a brief summary of the investment management fees, compared with the usual benchmarks (40 basis points, or .4%, would be a common standard). However, an agenda so mercilessly sparse seems an inadequate reason to convene a group of worthies for an hour, and quite commonly the committee will chat about investments in general, hoping to pick up some personal pointers. A good tip or two makes the whole effort seem worthwhile.

On one such occasion in 1987, the famous Quaker surgeon Jonathan Rhoads, Sr was chairman of the committee. The manager of the endowment was a handsome fellow whose picture had occupied a full page of the New York Times financial pages just a day or two before this particular meeting. The picture had been truly spectacular, the tailoring was remarkable, and he surely had perfect teeth. As this gentleman entered the room, the committee gathered around, slapping his back and congratulating him on his fame with great jollity. Little did the group know that within thirty days, the stock market would have its most severe drop in almost twenty years. Unnoticed at first by the merry-makers, Jonathan Rhoads had sat down at the head of a perfectly empty long mahogany table, and was intoning to the empty seats, "We will now begin by reading the minutes of the last meeting of this committee". Visibly shaken, the group immediately broke up and took their seats.

Rhoads went on. We were now to hear the report of our portfolio by our manager. Proudly, it was noted that in February we had bought XYZ for 20, and in July we had sold it for 44. And in March we had bought ABCs for 60, and it now stands at 100. When he had concluded, the chairman said, "That's fine. That's just fine. But what bothers me is that point of confusion." Why, what confusion, Dr. Rhoads?

"The confusion between investment genius, and just being in a bull market." Later the same month, the stock market suddenly dropped 22% in one day, thus guaranteeing that no one in the room would ever forget the episode.

Quakers From the Indian Point of View

|

| William Penna and Indians |

The following property of the Nicholson family has been presented to the Haddonfield Friends Meeting in replica form. Although signed by John Haines, it is not readily apparent why this member of a very old New Jersey Quaker family was being addressed, just what it means that he signed it, or possibly whether John Haines was a name adopted by Corn Planter. Very likely, however, Haines was acting as public scribe, a common profession in all illiterate societies. As a matter of fact, there have been so many Joseph Nicholsons that it takes some tracing to identify just which one he was, too.

------------- To the Children of the friends of Onas, who first settled in Pennsylvania:

The request of the Corn Planter a Chief of the Seneca Nation --

Brothers, The Seneca Nation see, that the greater Spirit intends that they shall not continue to live by hunting, and they look round on every side and inquire who it is that shall teach them what is best for them to do. Your fathers have dealt fairly and honestly with our fathers, and they have charged us to remember it and we think it right to tell you, that we wish our Children to be taught the same principles by which your Fathers were guided in their Councils.

NicholsonsBrothers, We have too Little wisdom among us, we cannot teach our Children what we perceive their situation requires them to know, and we, therefore, ask you to instruct some of them -- we wish them to be instructed to read and to write and such other things as you teach your own Children, and especially to teach them to love peace.

Brothers, We desire of you to take under your care two Seneca boys and teach them as your own, and in order that they may be satisfied to remain with you and be easy in their minds that you will take with them the son of our interpreter and teach him also according to his desire.

Brothers, You know that it is not in our power to pay you for the education of these three boys, and therefore you must, if you do this thing look up to God for your reward.

Brothers, You will consider this request, and let us know what you determine to do -- If your Hearts are inclined toward us, and you will afford our Nation this great advantage, I will send my son as one of the boys to receive your instruction and at the time which you shall appoint.

Signed February 10. 1791 -- in the presence of Joseph Nicholson

his Corn X Planter Mark

John Haines

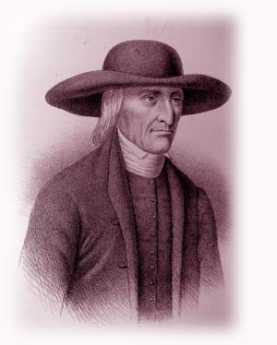

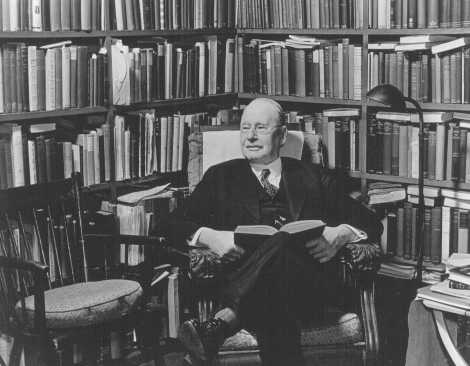

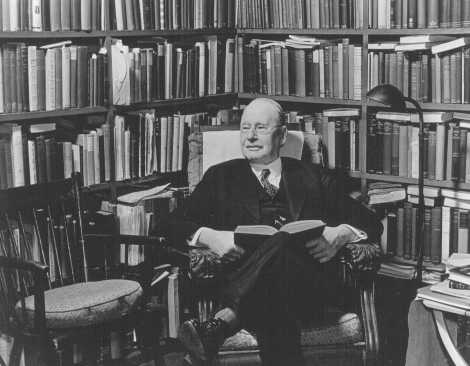

Rufus Jones, Quaker

|

| Rufus Jones |

Rufus Jones (1863-1948) dominated the Quaker religion for two generations, causing a transformation which deserves to rank with that of George Fox, William Penn and Elias Hicks. A few elderly Quakers still remember him in person, mostly as an old gentleman who tended to lean back while he spoke, usually hooking his thumbs in the sides of his vest. He was a prodigious writer, having once made a promise to himself that he would read a new book every week, and write a new book, every year. He kept that up for thirty years.

|

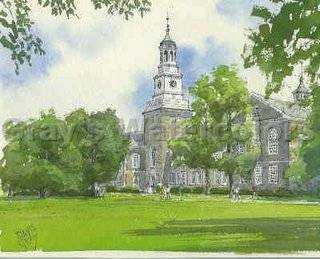

| Haverford College |

As a matter of fact, that understates his output. His published works were collected by Clarence Tobias at Haverford College, and run to 168 volumes, plus 8 boxes of pamphlets and articles. His family also donated his personal papers to the College, and they require 75 linear feet of shelf space.

His stated occupation would have been Professor at Haverford College, where his personal influence on the undergraduates was as profound as their influence was to be on the rest of the world. He is regarded as one of the founders of the American Friends Service Committee and the single greatest influence in reuniting the two divisions of Quakerism, although some of the formalities were not completed until after his death.

One other index of his remarkable energy was that he crossed the oceans more than two hundred times during his lifetime.

Perhaps the arrival of mass communication has made it possible to have equal impact with less effort. But Rufus Jones stands for the principle in life, that it never hurts to work just a little harder. If high school students are thinking of applying for admission to Haverford, they better understand what is going to be expected of them.

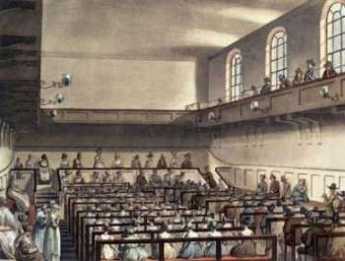

Silence Connotes Assent: Only To Quakers

|

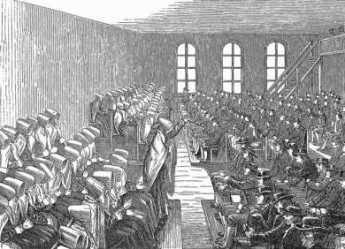

| British Parliament |

In 1604, the British Parliament considered the issue of what it should mean if Parliament remained silent on a topic. The English Civil War, King Versus Parliament, was soon to begin, so it was almost inevitable that Parliament would decide that in no sense, no way, was consent to be assumed from its silence. This common law principle endures to the present, and has been explicitly reaffirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the past few months. On an even simpler level, what is it to mean if the presiding officer called for the ayes, failed to solicit discussion or nays, and declared the matter settled? That's a fairly common error of inexperienced presiding officers -- and it's a common trick of manipulative partisan presiding officers, too.

|

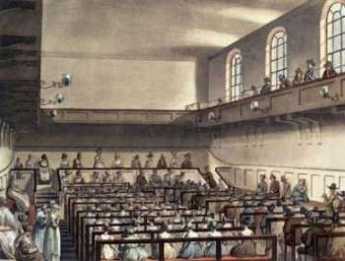

| Quaker Meeting for Business |

Parliament soon made the 1604 declaration that if the presiding officer failed to call for the nays, the motion was not carried, no matter how many ayes there appeared to be.

In Quaker Meeting for Business, however, the reverse is true. A proposal is made and discussed until discussion ceases. At that point, some weighty member will announce, "I approve", and usually there will be a chorus of other approves. If there is further silence at that point, the matter is carried and entered into the minutes, which are read aloud for comment and correction, before the meeting adjourns. It's really remarkable how much business can be accomplished in an hour, using that procedure.

The essential difference is that the Quakers are striving for unanimity, while courts and parliaments are striving for a decision. If the issue is whether or not to tax activity or to hang a criminal, it is probably futile to hope for unanimous consent. The stated need here is to come to some judgment, any judgment, in a timely fashion. The Quaker goal is to reach consensus, which may take some members longer than others, but the assumption is that everyone will eventually get to the same point. One group counts votes, with the chairman casting the deciding vote in the event of a tie, while the other group holds a matter over to another meeting until a significant consensus emerges.

The irony of this situation is that a group which sincerely strives for unanimity will actually dispose of its business more quickly than a group which forces the pace to meet some artificial deadline. The Quaker system does break down when the urgency for a decision is greater than the pace of reaching unanimity. The Parliamentary system breaks down when the number of votes (whether a majority or a super-majority) required for a decision, is in fact less than that intangible level of agreement which keeps the organization from disintegrating.

Slaveowning Quaker Steps Up To The Plate

|

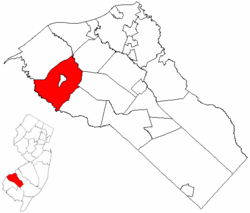

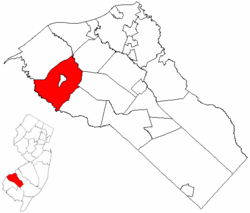

| County of Gloucester |

I, Joseph Nicholson of the Township of Woolwich and County of Gloucester, do hereby set free from bondage my Negro Tenor, aged about twenty-two years, and do, for myself, my Executors and Administrators, release unto the said Tenor, all my Right, and all claim whatsoever as to her person or to any Estate that may acquire, hereby declaring the said Tenor, absolutely free, without any interruption from me, or any person claiming under me.

In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my Hand and Seal this twenty-seventh day of the Twelfth Month, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy-nine. 1779.

. . . Joseph Nicholson (Seal)

. . Sealed and Delivered in the presence of Joseph Allen

The Definition of a Real Philadelphian (1914)

|

| Elizabeth Robbins Pennell |

There are several million people living in Philadelphia, but of course, not all of them are real Philadelphians. >Elizabeth Robbins Pennell, a friend and biographer of James McNeill Whistler, tells us the definition of a real Philadelphian in 1914.

"I think I have a right to call myself a Philadelphian, though I am not sure if Philadelphia is of the same opinion. I was born in Philadelphia, as my father was before me, but my ancestors, having had the sense to emigrate to America in time to make me as American as an American can be, were then so inconsiderate as to waste a couple of centuries in Virginia and Maryland, and my Grandfather was the first of the family to settle in a town where it is important, if you belong at all, to have belonged from the beginning. However, [my husband's] ancestors, with greater wisdom, became at the earliest available moment not only Philadelphians, but Philadelphia Friends, and how much more that means Philadelphians know without my telling them. And so, as he does belong from the beginning, and as I would have belonged had I had my choice, for I would rather be a Philadelphian than any other sort of American, I do not see why I cannot call myself one despite the blunder of my forefathers in so long calling themselves something else."

--Our Philadelphia, 1914

The Naming of Pennsylvania

On January 5, 1681, William Penn wrote a letter to his friend Robert Turner:

|

| Annals of Pennsylvania |

"This day my country was confirmed to me by the name of Pennsylvania, a name the King would give it, in honor of my father. I chose New Wales, being, as this, a pretty hilly country; but Penn, being Welsh for a head -- as Pennanmoire in Wales, and Penrith in Cumberland, and Penn in Buckinghamshire, the highest land in England, -- they called this Pennsylvania, which is the high or head woodlands, for I proposed (when the Secretary, a Welshman, refused to have it called New Wales), Sylvania, and they added Penn to it; and though I much opposed it and went to the King to have it struck out and altered, he said, 'twas past, and would take it upon him; nor would twenty Guineas move the under Secretaries to vary the name, -- for I feared lest it should be looked on as a vanity in me, and not as a respect in the king, as it truly was, to my father, whom he often mentions with praise."

John F. Watson, the author of what generations have called "Watson's Annuals," goes on to comment:

"If the cause was thus peculiar in its origin, it is not less remarkable in its effect, it being at this day perhaps the only government in existence which possesses the name of its founder."

Watson further makes the footnote: "Penn himself professed to have descended of the house of Tudor, in Wales, one of whom, dwelling on an eminence in Wales, received the name of John Pennunnith. He going afterward to reside in London, took the name of John Penn, i.e. John on the Hill."

The Schools of School House Lane

|

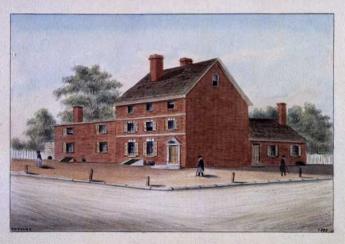

| Union School founded in 1759 |

The region of Philadelphia defined as Germantown is recorded by the last census as having about 50,000 inhabitants today, 40,000 of whom are of the black race. Germantown has always had an unusual concentration of schools of the highest quality, and here on one street alone there are four. School House Lane runs off to the West of Germantown Avenue, and was originally right at the center of town, the center of the action during the Revolutionary War. The most historic of the schools, the Union School founded in 1759, changed its name to Germantown Academy, and more recently picked up and moved to new quarters in Fort Washington. George Washington sent his nephew there, and its building served as a hospital for the wounded in the Battle of Germantown. When Germantown Academy moved out of Germantown, the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf moved into the vacated quarters. This school had been originally founded in 1820, and is one of nearly a hundred special schools for the deaf in the United States, operating as a quasi-public institution for about 170 students. A remarkable thing about all schools for the deaf is the high IQ of their students. Perhaps deaf underachievers are somehow filtered out by the struggle to adapt before they apply for admission, or perhaps there is something about being deaf that makes you smart. In any event, the average SAT scores of students from PSD, like all schools for the deaf, are always in the very highest ranks among secondary schools.

|

| Sklar School Entrance |

More or less next door to it, fronting on Coulter Street, is the Germantown Friends School(GFS), which enjoys and deserves the reputation of the most intellectually rigorous school in the Philadelphia region. There is little question about the Quakers of this school, founded in 1845, but relatively few of the students are now Quaker children. It's pretty expensive and quite uncompromising about its academic standards, but if you want to be accepted by a famous University, this is the place that can boast the most achievement of that variety. By no means all of its graduates become teachers, but alumni of this school do tend to gravitate to the top of academia. That could eventually put them on college admission committees, of course, and perhaps the admission process promotes itself. There can be little doubt that if most of a given college's admission committee happened to play the tuba, that university would soon fill up with tuba players.

|

| William Penn Charter School |

Further West on School House Lane, is the William Penn Charter School. It's also Quaker, and while it doesn't work quite so hard at it as GFS does, it has plenty of social mission, a great deal more discipline, and plenty of competitive athletics. A minority of its students, also, are Quakers; but as a guess, most of its graduates are headed for disproportionate affluence anyway. The middle school is named for, and was donated by, the former chairman of Morgan Stanley back before Morgan Stanley sold itself to Dean Witter. This school was founded in 1689, and for a long time was located at 12th and Market Streets in Philadelphia, right where the famous PSFS building was built, the one that later converted to Lowe's Hotel .

Finally, near the crossing of Henry Avenue with Schoolhouse Lane, is the Philadelphia University. Since it was founded in 1999 it is the youngest of the schools on School House Lane, specializing in architecture and design, and seems headed for even broader curriculum. The University was formed by the merger of Ravenhill Academy for Girls, and the Philadelphia Textile School. The Textile School was itself formed during the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, when local industrialists became concerned with how backward America seemed in its quality and design of textiles, compared with other nations which exhibited at that World's Fair. Next door, was once the home of William Weightman, a chemical manufacturer who was reputed to be the richest man in Pennsylvania. After his death, the rather grand estate became the site of the Ravenhill School for Girls, which was the school which could boast Grace Kelly for an alumna. That was natural enough since she lived just around the corner on Henry Avenue and could walk to school. The contrast between the two ends of School House Lane, Henry Avenue on one end, and Germantown Avenue on the other, is just astounding.

So there you have School House Lane. A few short blocks with three distinguished preparatory schools and a university. Plus, the site of three other famous schools which have either moved or merged. You might think Germantown was the home of myriads of school teachers, but that isn't exactly so. It's hard to say just what this complex anomalous situation proves, except to voice the opinion that it is somehow at the heart of what Philadelphia really is.

Note, kind readers have also sent me the names of six more schools on Schoolhouse Lane. Some of them may only be name changes, but the list includes Parkway Day School, Sklar School, Philadelphia Textile and Science, Germantown Stevens Academy, Germantown Lutheran Academy, Greene Street Friends School. (See Comments.)

Quakers Turn Their Backs on Power

There have been a number of excellent books about Ben Franklin lately, but all take his side in the dispute with Quakers. These authors relate Franklin struggled with the Quakers, fought with that political party, heroically overcame them with wisdom and guile. Good thing, too, or we all might still be subjects of the British crown.

Well, within the Quaker community these events are viewed differently. Around the year 1755, the Quakers who owned and ran Pennsylvania abruptly turned away from politics and left the government to their political enemies, rather than compromise religious principles. It is difficult to think of any other instance in history when a ruling party decided to become humble subjects of the opposing party, simply because they refused to do what obviously had to be done.

The background of this perplexing issue goes back to the founding of the Quaker colonies, which had lived in a real Utopia for seventy-five years. Repeatedly it had been true that if they just followed the highest principle, things worked out well for everybody. For example, they didn't need to buy the land a second time from the Indians, but they did, with the gratifying result of peaceful co-existence while other colonies experienced constant Indian wars. Penn negotiated the borders of his states with the neighbors, and although it took decades, brought peace and prosperous trade in return. Strict honesty in mercantile matters led to a reputation for trustworthiness, and that in turn led to prosperous commerce. Using a fixed price rather than haggling over price speeded up transactions, gained respect for fair dealing, led to more prosperity. Just you do the right thing, and all will be well. That includes extending freedom of religion, welcoming strangers to the colony to worship together in peace.

Toward the end of this Utopian period, some questions began to arise. More and more non-Quakers came to the colony, making the colony progressively less Quaker. That was a silent disappointment to William Penn. The founder had been a charismatic evangelist for his religion as a youth but came to grave disappointment about peaceful persuasion by the end of his life. Convincing the adherents of other religions of reasonable Quaker principles had often proved to be as intractably difficult as arguing religion with Henry VIII. The Quakers, a religion without a clergy, were appalled that so many adherents of other religions did not concern themselves with earnest reasoning, preferring to do strictly what their ministers told them to do.

Another disconcerting thought was growing within the Quaker community that success itself might be corrupting them. Worldliness seemed to grow inevitably out of wealth and prominence; all power does tend to corrupt. If you are rich, people always seem to steal from you, and that leads to violent punishments, something regrettable in itself. These were not new arguments, but by 1750 nearly a century of success in paradise had begun to stir Pennsylvania Quakers to wonder why more of their neighbors did not ask to become Members. These were troubling concerns of the day which would probably have worked themselves out, except that far-away France and England declared war on each other. The French responded by stirring up the Indians along the Western frontier. Pennsylvania settlers were soon scalped, kidnapped and burned at the stake. Something had to be done about it since protection was a duty of government, and effective protection now had to be non-peaceful. The Quakers dithered. More Scotch-Irish settlers around Pittsburgh were slaughtered. The Quaker meetings sent minutes to the Quakers in the legislature that they must not compromise their peaceful principles, and the Scotch-Irish exploded with rage. The Meetings told their representatives to resign from office, their members to retreat from politics altogether.

So Ben Franklin rose to the occasion, and General Forbes led an army to Fort Duquesne at the forks of Ohio, and Colonel George Washington was the hero of that day. The French were driven off the frontier, the English were victorious at Quebec. North America became a British continent.

Meanwhile, the Quakers retreated into tight-lipped solitude. And self-doubt, because the episode seemed to demonstrate that rigidly peaceful principles cannot govern a state or a nation if that nation contains others unwilling to be sacrificed for peaceful principles. An unthinkable logic emerged; freedom of religion led to conflict with the duty of a non-violent government to protect its citizens. It began to be clear it was the duty of government to enforce its laws, by force if necessary. Underneath the pile of documents, was a gun.

So, the Quakers proudly walked away from power and dominance, for all time. Sadly, too, because the significance was clear. Peaceful utopia may be not possible, within a dangerous world.

Keeping Lunaticks Off the Streets

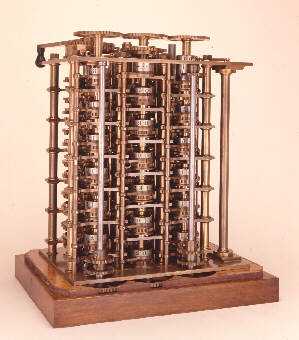

|

| Benjamin Franklin Print Press |

The Protestant Reformation provoked a wide variety of reasonings, and the Quaker position is at one extreme of them. One way of looking at it is to see the Reformation as largely a reaction to the invention of the printing press. At first, there was the impact of Latin versions of the Bible, or Vulgate, which could be read by priests like Martin Luther, and possibly interpreted by them to vary from established Church doctrine. Translation of the Bible into common languages subsequently permitted educated parishioners to read the Bible for themselves and draw their own conclusions. Fundamentalist branches of the church tend to place almost total reliance on what they can read for themselves, and consequently, authenticity is highly important to them. The Quakers go a step further, encouraging each member to come to his own spiritual viewpoint ("There is that of God in every man."), using the Bible as merely one important resource. Although others sometimes regard them as spiritually adrift, the Quaker idea is that if something is really true, everybody who thinks hard about it will eventually come around to much the same conclusion. (Related to this attitude is a strong belief in the ultimate triumph of democracy, and the essential rightness of market-set prices.) Some people try harder than others, of course, and they come to be regarded as "weighty" Friends, likely to have reached the correct conclusion somewhat sooner than others.

One very weighty Friend was Henry Cadbury, an American relative of English candy makers. Henry decided he wanted to spend his life teaching the Bible and went to Harvard Divinity School. He became in time the leading authority in the world on the Book of Acts, editing that section of the Interpreter's Bible, and rising to be Professor of Divinity at Harvard. Henry knew his stuff, so to speak.

|

| Henry Cadbury |

One fine summer day, Henry was seated in the front row of the Haddonfield Meeting. Birds twittered outside the open doors and windows, but otherwise, the gathered meeting was entirely silent. It was even beginning to look as though this meeting would be one of those occasional instances when nothing is said for an entire hour -- a "silent meeting". But, no, a visitor came through the open back door of the meetinghouse, in response to the sign found outside almost every meetinghouse, "All Are Welcome". The man was evidently a fundamentalist, and seeing a large audience all sitting silently waiting for something, he advanced boldly to the front of the meeting and began to speak.

The Bible was the Word of God. Every word in The Bible was true -- literally, and incontestably true. The theme was repeated several times, without an apparent response from the audience.

Finally, Henry Cadbury stirred himself. "Well, it has always struck me...". Oh, oh. Look out, here it comes.

"It has always seemed to me, that the most quotable parts of the Bible, are mainly based on the faulty translation."

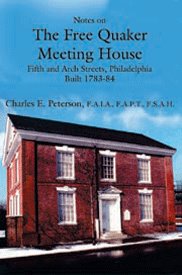

Free Quaker Meetinghouse

|

| Independence Hall |

Until this year, there was a Beautiful Mall stretching north from the State House (Independence Hall) to the approaches of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Concealing an enormous parking garage underneath it, the surface looked like a several-block lawn lined with flowering trees in the spring, framing the beautiful Eighteenth Century building (just as the mall in Washington leads up to the Washington Monument.)

Stretching from Independence Hall east to the Delaware River is another mall filled with historical buildings like Carpenters Hall , the First Bank(Girard's) and Second Bank (Biddle's), the Old and the New Custom houses, the American Philosophical Society, and others. The eastern mall was the property of the State of Pennsylvania when it was created, but it soon seemed more economical to the frugal rural legislature to turn it over to the federally funded National Park Service, joining the mall stretching northward. Well, somebody got another ton of federal money appropriated, and now we are filling the north mall with buildings which largely hide Independence Hall from the passersby. With just a few more Congressional earmarks, the imposing beauty of the mall will be submerged, but it hasn't quite reached that point yet. There is a perfectly enormous New Visitors Center, containing a couple of auditoriums and a big bookstore. Mostly the concept seems to be to provide a place to get out of the rain if you are an out of town visitor, provide public bathrooms, and a place to get a hot dog. At least the visitors center is red brick, and arched, with white woodwork. At the far northern end is an overwhelming stark granite block of a building, which will open July 4, 2003. It is a Constitution Center, claimed to be an interactive museum, and we shall see what we shall see. The looming monolith overwhelms and blocks the view to Independence Hall, and it better be good, when the insides get finished.

|

| Free Quaker Meeting |

If Independence Hall, which after all is a block long, is overwhelmed by the new constructions, the Free Quaker Meeting is totally hidden. This perfectly charming Eighteenths Century Quaker meetinghouse is just across Fifth Street from Benjamin Franklin's Grave, and just across Arch Street from the Constitution thing, completely in its shadow. Charles E. Peterson designed the restoration of the building, which had been added to and detracted from, over the years, but you can be sure its interior is now both beautiful and authentic. Before you go in, notice the inscription on the plaque under the northern eaves:

By General Subscription for the FREE QUAKERS. Erected in the Year of OUR LORD 1783 and of the EMPIRE 8.

The Quakers who built this building seem to have thought they were part of a new empire, but that implies an emperor, and of course, one was never created. Three years after the dedication of this building the Constitutional Convention met in the same Independence Hall, and our national form of government was somewhat strengthened from the Articles of Confederation also written here. Benjamin Franklin had a hand in both documents, but the first one was mainly composed by John Dickinson, and the second one by James Madison. If you go into the Free Quaker building, it seems to be a single large room with an interior balcony, and a couple of small staircases in the back leading down to what would presumably be restrooms. As a matter of fact, the Park Service extended the basement to include kitchen and dining room, and several offices for themselves which are a surprise if you are allowed to go down to see them.

|

| History of Free Quakers |

Charlie Peterson wrote a book about the restoration, but the main book about the spiritual history of this group was written by Charles Wetherill. Quakers, as everyone ought to know, are pacifists. The American Revolution put a number of them in a quandary because they agreed that Great Britain was injuring their rights by denying them a representative in the Parliament which ruled them but resorting to violence was another matter entirely. Eventually, a group did break away from the main Quaker church to fight for independence. They were prompt "readout of the meeting", the equivalent of being excommunicated, not allowed to worship in the regular meeting houses they had helped finance or to be buried in the church graveyards. Samuel Wetherill was one of the leaders of this group, just as his descendants are the most active today in the surviving historical society. Samuel created quite a furor, demanding to use the Orthodox meeting house and burial grounds. He was, in his own view, just as much a Quaker as the others since no doctrine is absolutely fixed in that religion, and was freely entitled to speak his mind to persuade others of the rightness of his sincere positions. The main body of Quakers would have none of it, and the Free Quakers were firmly expelled, forced to hold a public subscription and build their own meeting house. Wetherill of course personally knew every one of the members who expelled him, and there may be some truth to his loud, pointed and unchallenged contention that the true division was not between pacifists and fighters, but between Tories and advocates of Independence. Whatever the truth of these accusations, it does seem in retrospect that the split was fairly divided between wealthy established merchants, and small shopkeepers and artisans. Quite a few now-famous names appear on the rolls of the Free Quakers, like Timothy Matlack the actual Scribe of the Declaration of Independence document, Biddles, Lippincott, John Bartram,Crispins, Kembles, Trippes, and Wetherills. When the meeting had dwindled down in 1830 to two lone parishioners, one was a Wetherill, and the other was Betsy Ross, herself.

A comment is submitted by a reader:

I think your description of the Free Quakers oversimplifies their origins. It is true that Samuel Wetherill was disowned by Friends for his military activities. However, other Free Quaker leaders were bounced -- often years before the Revolution -- for other reasons. Timothy Matlack, for not paying his debts. Betsy Ross, for an improper marriage. Christopher Marshall, for counterfeiting. I haven't traced everyone listed as a member in the (1907?) Stackhouse history of the Free Quakers. But I did search in Quaker records for perhaps a dozen and found no records that people with those names had ever been Quakers. I think it would be more accurate to say of the Free Quakers that the Revolution drew together people of many different types and that when some of those people had things in common -- such as Quaker background -- they united around those things. (Posted by Mark E. Dixon )

The No-Doctrine Doctrine

|

| quaker |

Although Quakers have long been famous for good relations with the Indians, both groups strongly prizing simplicity and keeping your word, few Indians converted to Quakerism. Indians would attend the silent meetings and listen respectfully, but in the end, Christian converts were far more likely to convert to the Moravian Church. To resist defining your common beliefs creates automatically a problem for explaining what you believe. It becomes acceptable to believe a wide range of things, but it is also acceptable to believe very little. Not surprisingly, the two great religious schisms of the Quakers have broken their unity on just this point.

|

| A History |

The first great Quaker schism was created by one George Keith (1638-1716), who was born a Presbyterian and died an ordained Episcopalian. For several decades, however, Keith was one of the foremost leaders of the Pennsylvania Quakers, partly as a result of being just about the best-educated man of the Colony. His leadership, however, led him to crave a more defined set of Quaker doctrines, and when he carried this idea too vigorously, he eventually encountered implacable opposition which in time caused him and his considerable number of followers to be expelled from the Society of Friends. (George Keith should not be confused with Sir William Keith, whom Hannah Penn appointed as governor of Pennsylvania in 1717.)

|

| Elias Hicks |

The first great schism was thus about whether there might be too little defined doctrine in Quakerism. The second great schism, by contrast, grew out of the feeling there was too much doctrine. Led by Elias Hicks in 1830, the Hick sites split off from mainstream Quakerism in a quest for more simplicity, less religiosity, more silent contemplation of the Inner Light. In a sense, the outward show of protest in the black hats, plain dress, the plain speech had provoked a reaction that these things were no longer simple, they were ostentatious. Too many people were being "eldered", too many people were being "read out of the meeting" for violating doctrinal rules.

Curiously, both rebels were cast out, but over each following century the church as a whole gradually adopted what was largely their view of things. After Keith, Quakerism became more rigid and formalized. After Hicks, it became more mystical and free-thinking.

By insisting that in spite of turmoil it caused no doctrine was to be defined, Quakers have edged into the negative position of defining what they are not. Unlike the early sects of Christianity, Quakers have discarded the hope of miraculous divine intervention as a reason to behave in a Friendly Christian way. No one is apparently going to revive your bones from the tomb, feed your multitudes with forty loaves, or descend from Heaven and drive your enemies into the sea. Neither a later reward in Heaven nor a forthcoming everlasting punishment in Hell can be regarded as either very likely or much of an incentive to good behavior. Other religions may believe these things and might even turn out to be right, but Quakers feel the unembellished Golden Rule is a sufficiently understandable motive for conduct.

And gentle indirection is often a better way to persuade others than thundering oratory. The story is told of a visitor who found himself in a Quaker gathering and made polite conversation by asking what the Quaker position was on the Trinity. A sweet old gentleman is said to have smiled and said, "We believe in the following Trinity: The brotherhood of man, the fatherhood of God -- and the neighborhood of Philadelphia."

The American Friends Service Committee

Two things uniquely characterize the work of the Friends Service Committee (AFSC): it's often both dangerous and unpopular. That's not required for relief following Indonesian tidal waves perhaps, but the work that really needs someone to do is often both dangerous and controversial.

|

| Rufus Jones |

The Service Committee was founded in 1917, mostly by Rufus Jones and Henry Cadbury, as a way of helping conscientious objectors to World War I. The Mennonites, the Brethren, and the Quakers were opposed to all wars, not just that particular one, but two of those religions are of German ancestry, and lacked the same credibility of the English-origin Quakers in a war with English allies against the Huns, Boche, and Kaiser enemies. The early focus of the Committee was on the Field Service, or Ambulance Corps; which was plenty close to the action, and plenty dangerous. After the War, the defeated German population was starving, and the Quaker Herbert Hoover directed the relief effort with great credit to the Quaker name, and immense European gratitude.

|

|

Reinhard Heydrich was the primary organizer of the mass murder of Jews in the Third Reich. |