1 Volumes

Rt. Angle by Years

The history of Philadelphia"s finest men's club.

Right Angle Club: 2015

The tenth year of this annal, the ninety-third for the club. Because its author spent much of the past year on health economics, a summary of this topic takes up a third of this volume. The 1980 book now sells on Amazon for three times its original price, so be warned.

The Right Angle President Letter: Carter Broach

Right Angle 2015 Speakers

Right Angle 2015 Speakers

Note. Jan. Speakers Arranged by others, 2015 program chair not present.

Feb. 6 John Caskey, Ph D (Philadelphia SD Finances and Governance.) Feb. 13 Jeffery La Monica, Ph D (Chemical Warfare in WWI.) Feb. 20 Tony Junker (Peace Museum for Philadelphia. ) Feb. 27 Joel Spivak (Subways Around the World.)) Mar. 13 Bob Fernandez, Inquirer (Net Neutrality; How, What, Why?)) Mar. 20 Rodger Lane, Ph D (History of Crime.)) Mar. 27 Chad Bardone (Peace Corps Then and Now.)) Apr. 10 Krystak Appiah (Northern African American Experience post Civil War.)) Apr. 17 Robert Margolskee, Ph D & MD (How Taste & Smell Relarte to Health.)) Apr. 24 Michael Comfort (How the Navy Won the Civil War.)) May. 1 David Specca (Environmental Agriculture & Bio Engery.)) May. 8 David Richman Walter Russell, (Self Bestowed Genius.)) May. 29 Frank Bell (The Soga Brothers, Art and; Revenge in Japan.)) June. 5 Zenos Frudakis (Philospher in Clay.)) June. 12 Stephen Clowery (Leica and the Birth of 35mm Photography.)) June. 19 Bruce Mowday (Pickett's Charge; The Untold Story.)) June. 26 Berine Enright (A Fresh Look at George Washington.)) July. 10 Allan Brink ( Spring City Electrical: An Endurning History.)) July. 17 Ina Lipman (The Children's Scholarship Fund.)) July. 24 Thayer Schroeder (History of WaWa.)) July. 31 Jose Benitez (Needle Exchange in Philadelphia.)) Aug. 7 George Strimel (SEPTA in Motion.)) Aug. 14 Ned Rauch-Mannino (Marcellus Shale Gas Use Impact on Philadelphia.)) Aug. 21 Patrica Dickey (Brazil-Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.)) Aug. 28 Jason Mayland (Charter School Successes and Failures.)) Sept. 18 Ted Burkett ( Las Pozas: An Eccentric Englishman's Mexican Fantasy>) Oct. 2 Eugene DiOrio ( Lukens Steel and Rebecca Lukens.)) Oct. 9 M. Fredric Riedersd, Ph D (Last Chance Crime.)) Oct. 16 Donna A. Bilak, Ph D (The Chymical Cleric: the Remarkable Story of John Allin, Puritan Alcchemist.)) Oct. 23 Jeffery H. Johnson, Ph D ( From Dyes to Destruction: The German Chemical Indusrtyin WW I.)) Oct. 31 Mary Anne Eves (The 1876 Centennial in Philadelphia: America's First World's Fair.)) Nov. 6 Al Markle (Vietnam- A Veteran's New Perspective.)) Nov. 13 Allan Silverberg, et al (Holocaust Rememberance.)) Nov. 20 David Hollenberg (University of Pennsylvania's Architecture.)) Dec. 11 Dominc Tierney, Ph D (The Right Way to Lose a War to Lose a War: America in an Age of Unwinnable Conflicts.) Dec. 18 Matt Duppee ( Men's Clubs in Philadelphia and Beyond.))

Economic Proposals For 2015-16, A Trial Balloon

Glenn Hubbard, former Chairman of George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisers, has written his proposals for 2015-2016 as an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, in January 2015. The choice of newspaper probably has some significance, since the Chairman of a President's Council of Economic advisers sometimes does, and sometimes does not, formulate the economics views of his party and his President. It's possible he seeks to influence the role of his party's Congressional leaders or possibly represents the views of the two former Bush Presidents, or even a variant of them meant to influence Jeb Bush in his run for the 2017 Presidency. Time will probably tell, as the last two years of the Obama second term could be a time of compromise or time of bitter dissent. Hubbard makes ten or eleven points, usually as single-sentence assertions without associated arguments.

Broadened Budget Neutrality. The first point is that Congress has long been working within the boundaries of tax neutrality for any changes in the tax revenue derived from individual social or economic classes, a restriction Hubbard feels is unnecessary. The example he gives is corporate income taxation, which is very likely the area he had in mind. Perhaps, I think he is suggesting, corporate taxes could usefully be lowered without considering the personal benefits to the upper class of corporate stockholders. In effect, Labor Unions are seen to be acting out the attitudes of the Molly Maguires, in which only cigar-smoking plutocrats would be gaining if the corporations they own were taxed less. In the Gilded Age, perhaps family-owned corporations were the norm, but for fifty years American corporations(but strangely, not German corporations) have been stockholder-owned, or even index-fund owned. And if not officially, individual retirement assets are a growing part of every family's savings. There was a time when only rich folk owned stock, but nowadays employee pension assets have become a growing power in the marketplace. Double taxation is much less a class issue than formerly, and perhaps even cigar-smoking union bosses can be persuaded to change their stance and their rhetoric. Lowering corporate taxes might well help the working class more than the top one percent of earners if matters were scored in a balanced way.

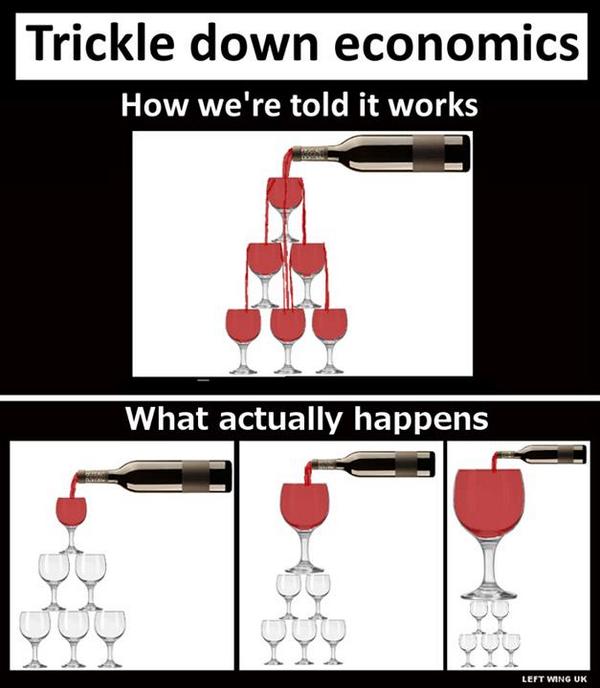

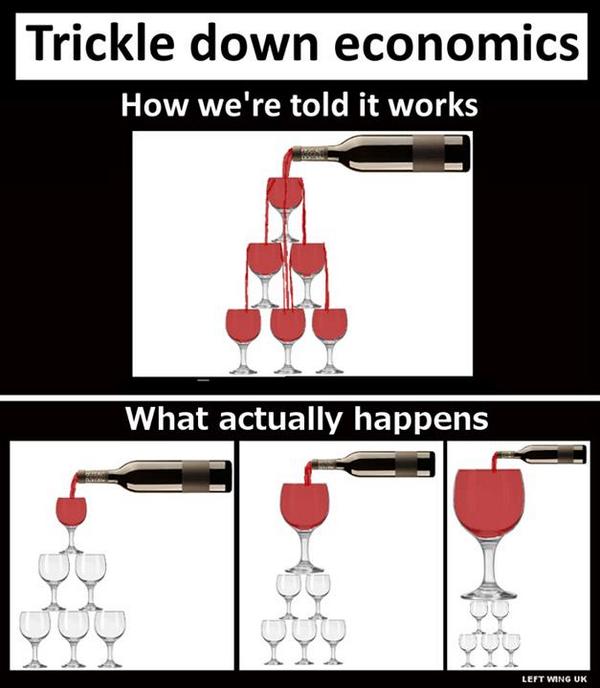

Flattening the Steep Step A second point is made that increasing subsidies and tax credits for the poor, leads to a steep step up to employment and a sudden loss of subsidies, as a further hindrance to joining the workforce. Deriding the loss of subsidies as favoring the "trickle down" process, is an unfortunate obstacle to searching for more gradual approaches to general prosperity.

Consolidated Business Tax. An effort to achieve a gradual transition is suggested, of a consolidated business tax rather than industry taxes and exemptions, and very likely a gradual merger of the customary bank loans, versus bonds. There is a sound of general plausibility about this, but no reasoning is offered in the editorial. Depreciation might be loosened somewhat for the general purpose of increased flexibility, but in general, the main area where depreciation ought to be made merely discretionary is in non-profit companies.

Specifying the Top Tax Bracket. It's interesting to read Mr. Hubbard's proposal to make the top bracket for personal income tax the same as the top bracket for business income. The reasoning behind this proposal is not given and is not immediately obvious. However, it does seem to be an improvement to have this issue removed from the class warfare language of "fairness", to be replaced by some other benchmark with a rationale. Hubbard similarly is inclined to replace subsidies to the poor with tax credits, a move which has the additional advantage of smoothing out the "steep step" up to income tax which is more graduated by effectively having more gradations than mere poverty versus no-poverty. Whether this is the underlying reasoning or not, anything which softens the Molly Maguire rhetoric of the 19th Century coal mines would be a step forward.

Health Care It certainly is heartening to see Health Savings Accounts recommended in both of the two alternatives he proposes for paying for healthcare, one with continued employer-based insurance and one with a tax deduction on the personal income tax. And it is certainly time for a way to be found to give equal tax deductions to those who pay for their own health insurance.

Educational Tax Deduction. A truly innovative proposal is made about tax deductions. Mr. Hubbard proposes a personal tax deduction for education and training, similar to the one already given for investment in technology and equipment. There's a question of whether this should be given to the individual or his employer, but that can be worked out in Congress. The idea is excellent, particularly when it is limited to out-of-pocket investments in education since it has the additional potential to address rising tuition costs while encouraging more education.

Block Grants. It is also innovative to consider block grants to the states to replace the tradition of making Federal funds conditional on state "cooperation", which the Supreme Court has begun to disapprove, as an invasion of states rights. This one might even rise to the level of a proposed Constitutional Amendment. There is little doubt the state legislatures are the weakest part of our federalized system, that the Supreme Court recognizes that fact, and leans toward attributing this problem to the system of conditional grants.

Consolidated Entitlements. Unless I am mistaken, there is a welcome proposal to address entitlement programs by consolidating them; and in the process begin to meet the looming issue of underfunded retirement costs. In a sense, the retirement costs are an outgrowth of improved health and longevity, a truly difficult problem created by a desirable effort.

Let's plan to review this program before the end of the year. By that time, it will have been tested in the fire of the adversary process. And since the following year will be disordered by-election campaigns, we can then surmise how much will be passed into legislation, how much will be exposed as impractical, and how much will fail passage but become the lore of long-term party positions in the far future.

2015 As Predicted from Pittsburgh

|

| Stuart A. Hoffman |

For the past 14 years, LaSalle University has featured an economics meeting at the Union League in January, usually with an economist predicting the local outlook for the year. Increasingly, the luncheon in Lincoln Hall has been packed and sponsored by some local firm. This year, the speaker was Stuart A. Hoffman, the chief economist of PNC Bank, who turns out to be quite a witty fellow. The lunch itself was gourmet, although a little on the feminine side for a mostly male audience. And because the place was filled with an audience, the waitresses of the League were taking it away faster than the eaters could eat it. It's hard to say what the audience might have felt about that, because most of them could afford to lose a few pounds, just like the Chef himself.

Dr. Hoffman feels the big news this year is OIL. It sort of fell out of heaven at the right moment, but even the politicians who opposed it are forced to acknowledge it was a very good thing, indeed. Its international effect, in creating oil independence, was especially powerful and undeniable. However, there are winners and losers. Our North American neighbors in Canada and Mexico may feel some painful effects, for example. In any event, the discovery and exploitation of fracking seem very likely to bring the recession to an end, sooner than we deserve, at least.

So the prediction for the year is rather bright for wages, unemployment, and housing, perhaps even banking. The relevant parts of the stock and bond market will prosper -- undeservedly, as always. But at the end of the year, we are likely to see that recovery as historical only, as we begin to see the long term gloom inherent in health care and educational costs, and the rest of the world begins to affect us more than we affect them. How's that for a January prediction, largely revolving around unexpected events in OIL. We'll try to remember to compare this January prediction with the subsequent December retrospective realities, later in this volume. We'll even see if Dr. Hoffman has to eat his words since today he had very little time to eat his lunch.

|

| Mario Draghi Chairman of the European Bank |

In the Question period, it was particularly interesting to hear a short description of what recently happened to the Swiss franc. The Swiss never joined the monetary union, but they did peg their currency to the Euro. As time went on, it was increasingly painful for Swiss exporters to have the franc suppressed by the lagging Euro, and when the Chairman of the European Bank announced his intention to start buying bonds, the Swiss bank capitulated and cut the tie of the Swiss franc to the Euro. The franc promptly rose, and that's all there is to the matter. Except if it isn't. The Germans are in much the same position within the Eurozone, and the English are restless, outside of it. So, if the prosperous parts of Europe decide to follow the Swiss example, the whole European monetary scheme may be in trouble. And if Europe has a monetary convulsion, it is trading partners in Africa and South America may follow, dragging in China, and -- who would be so brave as to suggest the USA could remain unaffected? Especially if Putin and the Arabs misbehave, pulverizing Israel in the process. When all you have is a hammer, you treat everything as a nail. Central Asia used to have two things, oil, and ruffians. And now they have apparently lost their dominance in oil.

|

| Andy Mellon |

Well, that's about the size of it, from Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh was largely settled by going West on the Erie Canal, so they never liked being attached to the Quaker end of the state. Philadelphia dominated with its banks, to Andy Mellon's great distaste, and largely controlled the shift of steel production from Eastern anthracite to Western bituminous coal. So now, Philadelphia scarcely has a bank to its name and has to hear the News of the World in Review -- from the other end of the state.

Two Chapters of the World Economy's History

World Economic History, Chapter One.

In 1972 Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger persuaded China to change sides. As a consequence, America and the Far East prospered, Soviet Russia collapsed, Europe devoted its attention to a twenty-hour week. The American consumer had a picnic at bargain prices, but it was too much of a leap for the Chinese consumer, so the party leaders prospered mightily from corruption, nepotism and casino gambling.

After America then over-invested in affordable housing, and Wall Street distributed the profits through the securities markets, their stock markets froze in a panic, then collapsed. The American government rescued Bear Stearns, but then reversed itself and refused to bail out Lehman Brothers. Its markets collapsed further, it is economy ground to a halt, and the Federal Reserve lowered long-term interest rates with Quantitative Easing, while Congress imposed the Dodd-Frank financial regulation bill.

The economy responded with a very slow recovery from the crash, and in seven years was still not fully recovered, except Quantitative Easing maintained abnormally low-interest rates, so the American consumer went on a spending spree.

World Economic History, Chapter Two.

By 2015, the Chinese consumer was getting restless because of failure to participate in the boom, so the Chinese premier clamped down on leadership corruption, plus devaluing its currency.

The Chinese leadership, who owned most of the stock, responded to what seemed like an attack on its privileges, by dumping its stock holdings; the Chinese market crashed, followed by the rest of the world to a lesser degree. The Federal Reserve had promised to raise interest rates but became fearful of making the crash worse.

The American stockholder had been told this was what had happened in the crash of 1937, which had been worse for the stockholder than 1929. Others said it was mostly a Chinese problem. The Federal Reserve continued to hold $3 trillion of Treasury bonds. During all this Keynesian activity, American inflation remained below its 2% target, at 1.5%, some say actually 0.3%. Manipulation of our currency or markets was suspected, a practically unheard-of event in view of our size.

So, what seems to have happened is the collapse of the Chinese stock market scared the wits out of the American stock market, which dropped like a stone. And that seems to have frightened the Federal Reserve into saying it wasn't so sure it wanted to raise interest rates, after all. So the American stock market shot up like a rocket, recovering most of its losses. It may be a happy result, but how many times can we repeat it?

And then, the Developing countries, which sell raw materials to China, dropped. And then Europe announced it was going to do Quantitative Easing, because -- horrors -- there hadn't been the inflation they hoped for. Which reminded everyone that Obama had spent more money than Congress appropriated, forcing the US to borrow more, or else shut the government down. The flood of Treasury bonds seems to be what holds down inflation since the market responds to a flood of bonds by lowering interest rates. Perhaps we do not need a debt limit, if the market imposes its will, placing a limit on borrowing. The American stock market is on the way down, unless Obama stops borrowing, or until Congress raises taxes. And, curiously, it seems to be China that gets hurt, first.

The Streets of Philadelphia, on Ben Franklin's Birthday

|

| Benjamin Franklin 309th Birthday |

They changed the calendar in the Eighteenth Century, so it's always confusing to talk about the birthdays of the Founding Fathers. Benjamin Franklin for example was born on January 6, 1705, but by the time he got around to being famous, he was born on January 17, 1706. Scholars handle this awkwardness by saying he was born on January 17, 1706 [OS, January 6, 1705]. That's not all the problem, however. This year on January 17 he had his 309th birthday, unless you wish to say he had his 310th birthday on January 6. The novelty has long since worn off, and nowadays most birthday celebrants prefer just not to mention the matter. You might think Don Smith would think this is of vital importance, but he cheerfully brushes it off with a chuckle.

|

| BenFranklin Celeabration |

Don Smith is the current leader of the Ben Franklin Birthday Celebration, which is held at 9 AM every year, on January 17th [NS], starting at the American Philosophical Society's Franklin Hall on Chestnut Street, once a very substantially-built bank building. The constituent members are affiliated with one of the thirty-odd organizations which Franklin founded, although anyone interested is welcomed. On what usually turns out to be the coldest day of the year, the birthday celebrants gather for hot drinks and cookies, followed by one or two really outstanding lectures about Franklin. Sometimes the lecture's connection to Franklin is a little stretched, but all of them are excellent. At 11 AM, the group marches together to Ben's grave at 5th and Arch for a short ceremony, led by Franklin re-enactors and honest-to-goodness members in the uniform of the National Guard, which Franklin founded. He did so when the Spanish and French ships were bombarding the coast, and as the editor of the town's newspaper, Franklin called for troops to defend us. The Quaker government declined to be violent, so Franklin published an invitation for volunteers to bring their guns and join him. Ten thousand showed up, and Franklin's career in public life was established. He was a hero to everyone -- except Thomas Penn, who saw him as a threat. Much subsequent Colonial history revolves around this episode and its consequences.

After the march, the group settles down for a good lunch, and hears yet another outstanding lecture. This year it was given by Paul R. Levy, the President of a planning organization called the Center City District. Steve's message this year was about how the streets of Center City Philadelphia were constructed for walking, or at most riding horseback. That is, they were narrow. They widened somewhat as they went West and had to accommodate a city of carriages. That was quite good enough through the Gilded Age, when Philadelphia could credibly claim to be the richest city in the world.

|

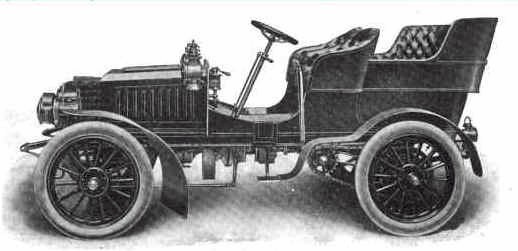

| Auotmoblie |

But then what happened was not the two World Wars, the stock market crash of 1929, or anything resembling that. What happened in Paul Levy's view, was the automobile. Hundreds, then thousands of autos filled the streets, scattering chickens and children, and eventually making the city impassible. Nothing would do but to move to the suburbs, which among other things provided the thrill of driving too fast and too carelessly, and reducing the pedestrians while increasing the business of accident rooms. There was certainly no room for bicycles, which were driven away without a tear being shed, and defying the efforts of city planners to find a safe place for them. Europe, good old Europe where we came from, was more successful in hounding the imposter autos off the bike paths of Amsterdam and Copenhaven. And preserving intercity high speed train service, at great taxpayer expense. Those Europeans really know how to live, in sidewalk cafes, unaffected by bicycles, preserving a much older collection of narrow city streets leading to empty cathedrals, in Germany, France, and Central Europe. That wasn't the American way, at all. We just pulled up sticks and moved to the suburbs, abandoning the dirty old defeated cities to their ethnic neighborhoods.

It's a novel theory, and maybe even a correct one. It could explain a lot, if Philadelphia is seen as a victim of Detroit, strangling on their mutual industrial excesses.

Suburb in the Big City

|

| Brown Brothers Harriman Co. |

In gathering views on what made Philadelphia deteriorate, a rather surprising response was given by Don Roberts, of Brown Brothers, Harriman. Don had obviously given this matter considerable thought, and without a moment's hesitation he answered, "The City-County Consolidation of 1858." For a few weeks, I puzzled over this answer, but my older daughter Miriam suddenly made it clear.

Miriam lives in Chestnut Hill, the suburb within the city. Her answer was made up of two anecdotes, relating personal experiences with city employees. The first had to do with the Water Department, which I had always heard was the crown jewel of the City bureaucracy. One day, she had no water in her house. Her first impulse, for whatever reason, was to call Roto Router. The nice man came and told her her pipes were fine, but the water had been turned off at the street, and he was forbidden to turn it back on. Happens all the time, he said, and he knew it was a waste of time to call anyone but the City. After several phone calls to the Water Department, the department sent out a man. At first, the Water Department denied they had turned it off. The next day a man came and, well, Yes, we did turn it off. Your next door neighbor hadn't paid her water bill, so we sent a man to turn off her water. He couldn't find her pipe, so he turned off the nearest thing he could find, which happened to be yours. After hearing my daughter screech in her best accent, they turned it back on. Sorry about that.

|

| Earth Day |

The second anti-city-consolidation episode was to discover a uniformed city employee rummaging in her garbage. Asked what he was doing, he announced he was fining her $85 for failing to separate garbage from the trash. After being told she was freakishly diligent in doing so and was in fact one of the founding members of Earth Day, he rummaged some more and found a cardboard box with some strawberry juice smeared on it. So, she took the next day off from work, went down to headquarters to spend the whole day, and had the satisfaction of having the fine removed. Her neighbors later told her, happens all the time. When it happens to them, they just pay the fine and shrug it off.

Those of us who live in the unconsolidated suburbs are universal of the opinion that neither of these episodes could possibly have ever happened in their suburb because suburban officials listen to the citizens. Come to think of it, I'll plan to ask Don Roberts where he lives, just to see if this was the point he was making.

River to River, Pine to Vine

|

| R. Bradford Mills |

Brad Mills, a former Marine officer who now is a Commercial real estate advisor for Tactix Real Estate Advisors, was recently on the podium of the Right Angle Club. His theme was the Decline of the Suburbs, creating a return to Center City. Although some other cities have experienced an even greater change, his point generally corresponds to everyone's experience. If Stephen Levy is right that the automobile choked center city to death in the 1920s, this reversal of fortunes would seem to correct the migration of a century ago. The big question is whether it will continue, once an economic recovery, and cheap gasoline prices, make the auto popular again.

|

| Center City Scene |

The Center City scene at present is summarized by its rental prices: $100 per square foot for offices, $400 per square foot for top-level residential. So, naturally there are a number of office buildings being transformed into either residential or mixed-use. And about 20% of office space is unoccupied. The offices themselves are being transformed into a style which absolutely no one likes. Open space offices with insignificant partitions between them. Even the top officers are forced to abandon corner offices in order to show the rest of the employees they are participating in the new style, which as mentioned, everyone hates. Another statistic: the office space averages ten units per 1000 square feet, instead of the more luxurious 4 per thousand, and more often single offices. SEI carries matters to some sort of extreme: desks on wheels can be gathered together for conferences, pulled apart to talk on the phone. And to make things even worse, this seems to be following a European style. Ugh. For one thing, no American likes to appear European. No one likes it when office space is "hotelized", sharing a desk between someone in the office and someone else who is on the road, visiting the trade.

|

| Comcast Building |

There's a lot of talk of Drexel showing us the future, but that's probably in the far future, when Drexel has to consider building over the West Philadelphia train tracks along the river, for dormitories or whatever. In time that may happen, but what's immediately in prospect is the second building Comcast is building next to the existing one. To a degree, the people who will fill the new building are already here, scattered out in vacant spaces around City Hall. When the building is finished, those people will move into it, leaving their existing space -- either empty, if the recession continues, or occupied with "secondary" offices if we recover from the recession in time. It's a time of anxiety for architects.

And the people? Well, we have a doughnut hole model. The top executives want to be in town, close to work, where the action is. And young couples want to save on commuting expenses, living close to work, using public transport, living close to other people their own age. Out in the suburbs, things are emptying out, prices are down, and "crazy money" from New York is moving in for what they imagine are bargains. It promises to be an exciting scene, full of action. But what's missing? School-age children. It won't be much of a normal city without some kids, and to get them you need good schools, public safety, and a shift in taxes from that 19th Century wage tax, to the more modern real estate tax. Meanwhile, our speaker has his own individual office -- in Radnor.

Gashouse Gang

|

| Electrician Union Logo |

A couple of lawyers from Community Legal Services dropped around to the Franklin Inn club, the other day. Someone in the club thought they might be able to shed some light on the recent sale, or rather frustrated sale, of the Philadelphia Gas Works and invited them over. They told us what they knew, but other luncheon guests came away with the impression they don't know the full scoop. It's for sure the newspapers don't know much, either.

|

| Philadelphia's Gas Company |

Philadelphia's Gas Company was started in 1830 and acquired as a City property in 1860. Before that time, an occasional mansion would have its own private gas house, fermenting gas for central lighting and heating, and apparently the scene of other carryings-on, leading to the derogatory title of "Gas House Gang". That was long before any thought of city corruption, or politics, or even professional Baseball. For nearly a century, municipal gas works would produce "Manufacturer's Gas" by fermentation of various discarded materials, but when the "Big Inch" pipeline was converted to natural gas at the end of the World War II, at least people stopped committing suicide with it (natural gas didn't work), and most cities sold the gas company to private owners. Gas work has long had the reputation of featherbedding and corruption, selective collection of gas bills, and a fair amount of graft. Perhaps much of this is a legend of the past, but I wouldn't bet much money on it. It suddenly got into the news lately, when a Connecticut company made a cash offer for PGW, the local gas company. The Mayor liked the idea and brought it to City Council, which refused even to consider it. The newspapers had recently had a run-in with Mr. Dougherty, the President of the Electricians Union, over the conviction of the union for arson of the Chestnut Hill Quaker Meeting House, and there's no doubt the news coverage of the Gashouse sale offered the public a dim perception of City Council politicians and their pro-union behavior.

|

| John Dougherty |

Our lawyer guests felt this was a little unfair. The Mayor did request a hearing on the matter, but he is not a member of City Council and needed a member to introduce the topic for discussion. After the Council President expressed an unfavorable position, no other member of Council was willing to introduce it. So the matter was dropped for lack of a sponsor. While there is little doubt much was beneath the surface, it is a little imprecise to say the Council blocked the matter from consideration. The next time the City Charter comes up for review, it would seem reasonable to allow the Mayor to introduce measures by himself, perhaps by giving him ex officio membership. Leaving him without some way to start a discussion, as he was humiliated to admit in public, does seem a little awkward. But it permits it to be said they actively blocked him, in this particular case.

|

| Gov. Tom Corbett |

Let's be sure we remember the biggest news in this state for a decade, has been the discovery of shale gas, leading to energy independence, low energy prices, and potential prosperity. Governor Corbett had refused to allow taxes on the shale extraction, and a lot of politicians had been counting on getting a piece of this action for their own local purposes. In the November 2014 election, there had been a Republican landslide across the whole nation, including the Pennsylvania Legislature. But Republican Governor Corbett was swept out of office, in a striking exception to the landslide. One of the visiting lawyers mused that Philadelphia's Democratic Mayor was probably looking for some state assistance in his struggling budget problems, and perhaps, just perhaps, that was the reason he was acting in such a wayward manner in this gashouse thing. No one was talking. After all, it was a common belief that gas transmission lines were all sewed up, many stronger politicians had got there first, and gas for Philadelphia was a non-starter. Since no one is willing to talk about it, everybody has a right to his own guess. Here's mine.

|

| James P. Torgerson |

A thing is worth what you can sell it for, not a penny more. The President of a Connecticut gas company presumably has something on his mind when he crosses two state lines to make an offer for some distant city's gas company. Two possibilities come to mind immediately, and one of them is immediately squelched. That would have been the idea that the acquiring company would plan to dump the defined-benefit pension plan of the city employees, and offer a defined-contribution plan like everyone else. But that idea had occurred to others first, and it had been testified the pension plan for the gas workers was actually pretty well funded. So, if that's a non-starter, there's only one other excuse the Connecticut gas president could offer to his own Board of Directors, for pursuing a $42 million cost to acquire a $30 million dollar savings, particularly when PGW already had the highest rates in the state and obviously wouldn't be able to raise them after a merger.

It would be my guess this talk about the hopelessness of getting a pipeline constructed, was bunkum. My suspicion is he had good reason to believe he could get a pipeline, and that a Republican president would approve it. Governor Corbett had already shown unusual foresight in attracting pipelines by refusing to tax shale gas. By the time he got the pipe in the ground, a gas glut would drop gas prices so severely no competitor in another state could compete with it. That's why the dimwits in the Legislature were so mad at him; they were expecting a joy ride on those taxes for themselves. Instead, we have taken a couple of steps toward making Pennsylvania the oil capital of a nation which has shale competition in forty other states. But Pennsylvania would have the pipelines. Poor Corbett got a political pistol-whipping, but if he has friends who owe him bigtime in the oil business, he won't be permanently sorry.

Philadelphia School Crisis

|

| John Caskey |

John Caskey, a professor at Swarthmore, recently visited the Right Angle Club to share his insights into the origins and potential solutions to the approaching collapse of the Philadelphia School system. The problem, everyone agrees, seems even more devastating in the light of the eminence of the Philadelphia schools, public and private, until very recently. While the elephant in the parlor is the 1940's migration of poor black people from the Southern states to the northern ones, it does seem to be true that the very eminence of the Catholic School system, and the Quaker private school system, has served to aggravate rather than rescue the situation. For example, when parochial schools are forced to close, there is no pool of tax money to transfer with them to charter schools. Philadelphia had been able to afford better public schools while the private schools supported themselves. But when their support diminished, their closure did not unleash any funds to help the public system. By contrast, when a public school closes, the tax money is transferred to the charter schools. One-third of all children entering Philadelphia charter schools are coming from parochial schools. It would be interesting to learn whether the total school budget, public and private together, had actually been less than it is today.

Without access to the specific facts, it would seem likely the number of children attending Philadelphia schools must have shrunk considerably in the past few decades. You can close or even sell, empty school houses, but pensions reflect the number of teachers when the city population was larger. Something like that seems plausible as an explanation for Philadelphia teachers receiving an average of $70,000 apiece, while at the same time, reliable figures seem to show an average per teacher employment cost of $110,000. Possibly true, but probably misleading. Almost everyone acknowledges we cannot afford the municipal pension system of the Great Depression of the 1930s, but it is almost too late to do much about those costs, magnified as they must be, by having a disproportionate amount of the school budget go to retirees.

|

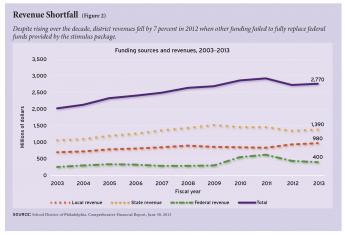

| Collapse of the Philadelphia School system |

The social intractability of the problem is brought out by some comparisons of the source of school revenue. Because Philadelphia is poor, while the suburbs are comparatively affluent, one would expect the suburbs to have a greater proportion of their school budgets derived from local property taxes. Actually, matters are exactly the reverse. Poor as it is, Philadelphia is supporting over 80% of school costs from local taxes, while the suburbs are much more supported by state and federal sources. The failing city school system is in fact draining the limited local real estate taxes away from other expenditures which might restore some of its affluence. And it isn't likely to restore the balance, any time soon. Real estate specialists refer to the "donut hole", by which they mean that parents of school-age children move away to better and safer schools. As soon as things improve somewhat, we can expect school children to flood back into town, bringing their expenses with them. We have yielded to expedients which in a sense represented our financial reserves. We must overcome this obstacle before much progress is even possible.

Even our political correct speech gets in the road of progress. There is a notable reluctance to blame the school problem on the migration of poor black people from the rural areas of the South, to the inner cities of the North. But it is plainly true; our resources have been overwhelmed by this phenomenon of the 1940s. Air conditioning did improve the livability of the South, drawing Northern industries Southward. Since this aspect of the issue is an interstate problem, federalism hampers the efforts to send tax money Northwards to balance things. We mustn't talk about things like that, right? To some considerable degree, this problem resembles the international balance of trade. When trade migrates in one direction, funds must migrate in the opposite direction. To whatever degree our fastidiousness of speech hampers this self-balancing, it makes the problem worse.

Tony Junker; Peace Museum

|

| Tony Junker |

The Right Angle Club was once again honored by a recent talk by Tony Junker, the novelist, retired architect, Center City resident -- and now the leader in an effort to start a Peace Museum. He's a Quaker, as Philadelphians would easily guess, and a charming peace advocate. He tells us his specialty while a practicing architect, was designing museums, so the whole thing starts to fit together. The museum is still in the planning stages, hoping to raise two million dollars as start-up money. Needless to say, Philadelphia has a long history of Quaker advocacy for Peace. It is not saying too much to suppose William Penn designed his whole colony as a peace demonstration. And Tony began his talk by noting that in England, Penn's father remains much better known than his son.

William senior conquered the island of Jamaica and gave it to King Charles, in return for which the King repaid his debt by giving the admiral's son Pennsylvania. On his deathbed, the Admiral beseeched his king to look after his rebellious and somewhat disobedient son; this was King Charles' way of doing it. By the way, he had distinguished himself with successful administration of New Jersey before the King gave him Pennsylvania, and acquired what is now the state of Delaware, somewhat later. With these three states, he became the largest private landowner in our history -- ever. He makes the Klebergs of the King Ranch look pretty paltry by comparison, and indeed Charles even offered to make him a vassal king. Young William, however, told him that really wasn't the idea, at all. Young Penn sold land to his suspicious co-religionists, and in order to facilitate the sales, drew up a document called, Concessions and Agreements , which was in considerable part a model for America's Constitution. It can be found in the Archives of the State of New Jersey, in Trenton.

|

| The Peace Museum |

The Peace Museum is projected to open in a few years; it would be a great mistake to underestimate Tony's ability to get it started. Since his retirement, he has founded a Quaker retirement community on Front Street which is already in existence. It's open to non-Quakers of course, and there are quite a few Quaker retirement villages in the suburbs. But Philadelphia is returning to Center City, and the need for a retirement home has often been expressed but never implemented until Tony came along. Early Quakers lived in caves along the banks of the Delaware River, just about where the retirement village is situated, and Quaker settlement later concentrated along Arch Street. Arch Street, by the way, really had an arch. Evidently, the river was once much deeper and somewhat wider, so it had one embankment which began at Front Street and a lower one on Water Street. So as the town grew, it was natural to undercut a tunnel with an arch bearing Front Street. Many houses eventually had one door on Water Street and another door on Front Street, higher up. Relics of Quaker settlement can still be noticed on Arch Street, cut off by the Benjamin Franklin Parkway slanting Northward. Front and Arch was the location for the main anchorage in those days, and the London Tavern at Front and Market was the main hangout of sailors off the ships nearby, a rich source of gossip and the origin of a number of rebellious episodes. The Fifteenth Street Meetinghouse now seems to be the most westward sign of this Quaker settlement, but Isaac Sharpless bought the land of Friends Select School further west and shared the land between Friends Select and his high-rise headquarters of what was the Pennwalt headquarters. If you are planning a Quaker museum in Center City, you can find plenty of choices to be called historic Quaker property, along Arch Street. The still earlier Quaker settlements around Dock Creek, beginning at about Spruce Street, have long been outgrown and abandoned.

Unfortunately, although we experienced long periods of Peace during the Nineteenth Century, it must be admitted that Penn's hope for an example of peaceful existence to the rest the world, would have to be called a failure. We have had several major foreign wars during the Twenty-first century, and show every sign of preparing for more. The Quakers literally owned a major portion of the American colonies and withdrew from politics rather than vote for war taxes in the Revolutionary War. While the example of courageous conscientious objection had its impact, it also developed an image of martyrdom which the rest of the world declines to imitate. Friends are perfectly capable of forming their own opinions, but it might be suggested to them that more of their efforts would be successful if somehow they made more publicity of their successes.

|

| Whiskey Rebellion |

George Washington, for example, was effective in keeping us out of foreign entanglement, in large part by the fact that he was a famous athlete and a successful warrior. His example for the country was in effect, "If you are strong, people leave you alone." He was surely successful in achieving a peaceful settlement of the Whiskey Rebellion by saddling up his horse and riding at the head of 10,000 troops in a threatening manner. Later in his presidential administration, he was surely more effective in dealing with European powers because of his former military reputation than he would have been without it. His second inaugural address was in effect a plea that good things could emerge from self-interest: Honesty is the best policy. There's a primitive quality to this appeal, reminding his countrymen they are more likely to get rich if they were honest, than if they were dishonest. Purists may squirm at the undertones of this motto, but surely it was effective with his countrymen. And three-quarters of the world's population might still be better off if they adopted a motto which falls just a little short of being altruistic.

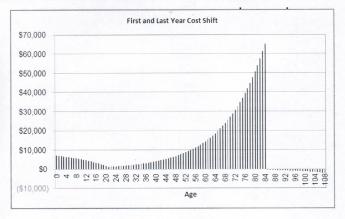

Paying for the Healthcare of Children

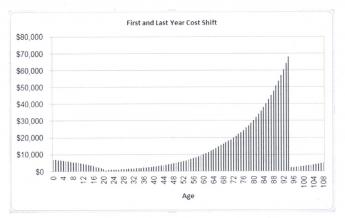

It has been said by others that eventually healthcare will shrink down to paying for the first year of life, and the last one. Right up to that final moment, medical payments must somehow evolve in two opposite directions. We might just as well imagine two complimentary payment systems immediately because the two persisting methodologies could eventually conflict unless planned for. Paying in advance is fundamentally cheaper than paying after the service is rendered because there is no potential for default in payment.

The two methods even result in different aggregate prices; in one case you pay to borrow, while in the other you get paid to loan the money. Dual systems are a fair amount of trouble; remember how long it took gasoline filling stations to adjust to credit cards versus cash. When gas prices eventually got high enough, they just charged everybody a single price, again. This isn't just lower middle-class stubbornness. Dual payment systems slow you down, and profit is generated from repeated rapid transactions. The buyer wants the goods and the seller wants the money. The profit comes from doing exchanges as fast and often as you can manage them.

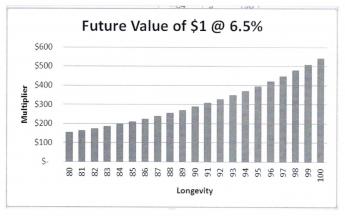

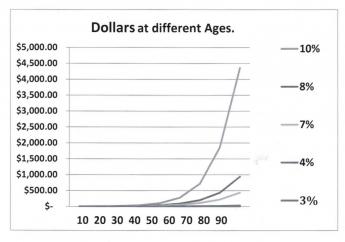

In a well designed lifetime scheme, with balances successively transferred from one pidgeon-hole to another, it becomes possible to maintain a positive balance for years at a time (thereby reducing final prices, because the income from compound interest keeps rising toward its far end). That was a discovery of the ancient Greeks, but sometimes Benjamin Franklin seems like the only person to have noticed.

The last year of life is more expensive, But the first year of life may cause more financial pain.

|

However, In real-life health costs, there is one intractable exception. Because obstetrics can be costly, particularly the high costs of prematurity and congenital abnormalities, the first year of life averages $10,500, or 3% of present total health costs. It, therefore, results in pricing which many young parents cannot afford, in spite of insurance overcharges to catch up later. And thereby a multi-year stretch of interest income is jumbled up, often lost entirely. It gets worse: childhood costs from birth to age 21 average 8% of lifetime healthcare. Please notice: Single-year term insurance premiums always rise to a much higher level than a lifetime, or whole-life, premium costs, because of internal float compounds in whole-life. Modern medicine has also resulted in rising lifetime costs, with only this obstetrical exception. Someone surely would have figured this out, except excessive taxation of corporations created a motive not to notice the effect on tax exempted expenditures.

This problem obviously could be approached by borrowing or subsidizing. Someone might even envision a complicated process of transferring obstetrical costs to the grandparents for thirty-five years, then transferring the costs back to the parent generation. Since we are describing a cradle-to-grave scheme, it seems much better to imagine a single person's costs eventually becoming unified. Grandparents do in fact share continuous protoplasm with grandchildren, but before that was recognized, the courts had decided a new life begins when a baby's ears reach the sunlight. Stare decisis beats biology, almost every time. A society which already has a high divorce rate and plenty of other family upheavals probably feel better suited to the principle of "Every ship on its own bottom." -- except for this financing issue. For childless couples and parentless children, some kind of pooling is possibly more appealing, and the complexities of modern life may eventually lead that way.

|

In the meantime, lawyers, who see a great deal of human weakness, are probably better suited to suggest a methodology for transferring average birth costs between generations, and back, although a voluntary process seems more flexible. It would seem grandparents are often most likely to be in a position to leave a few thousand dollars to grandchildren in their wills, and age thirty-five to forty seems the time when competing costs are at a lifetime low, making that the best time to pay it back.

Some grandparents are destitute, however, and some parents are basketball stars. There are surely generalizations with many exceptions. The process is happily simplified by a birth rate of 2.1 children per couple, which is also 1:1 at the grandparent/grandchild level and our Society has an unspoken wish to increase the birth rate if it could afford it. For legal default purposes, matrilineal rather than patrilineal descent may be more workable. But -- if every grandparent willed an appropriate amount to some grandchild's account, it would work out (with a small balancing pool), creating a small incentive for the intermediate generation to have more children.

The answer to this dilemma probably lies in revising the estate-resolution process, making HSA-to-HSA transfers largely automatic within families, devising a common law of special exceptions and adjustments, and creating a pooling system for special cases which defy simple-minded equity. A large proportion of grandparents have an indisputable defined obligation, and a large proportion of grandchildren have an indisputable entitlement. The difficult problems reside in the exceptions and require a Court of Equity to decide them. We leave it to others to fill in the details because there could be many ways to accomplish this, and some people have strong preferences. The basics of this situation are the grandparents with surplus funds are likely to die later, but they are still likely to die, close to the age when newborns are appearing on the scene.

When you get down to it, the problem isn't hard if you want to solve it. By arranging lifetime deposits in advance, a large number of grandparents could die with an HSA surplus of appropriate size. A large number of children will be born without a standard-issue family and need the money. After the standard-issue cases have been automatically settled, these outliers can be referred to a Court of Equity charged with doing their best. After a few years of this, the results can be referred back to a Committee of Congress to revise the rules.

A basic fact stands out: most newborn children create a healthcare deficit averaging 8% of $350,000, or $29,000, by the time they reach age 21. Most young parents have difficulty funding so much, and so all lifetime schemes face failure unless something unconventional is done to help it. A dozen more or less legitimate objections can be imagined, but seem worth sacrificing to make lifetime healthcare supportable. The main alternative is to pour enormous sums into the government pool, and then redistribute them. I am uneasy about letting the government get deeply mixed into something so personal. So, speaking as a great-grandfather myself, about all that leaves as a potential source of funds, is grandpa, and even grandpas sometimes have an aversion to long hair and rock music.

"Scores of Centimillionaires"

|

| John Bogle |

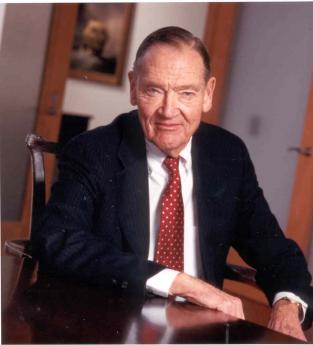

John Bogle is an investor with an evangelistic twist. He sold over 800,000 copies of his various books about Mutual Funds, donating the royalties to charity. One theme running throughout his writing is that no unmargined investment manager can focus exclusively on equities in his portfolio and expect to have a higher return than the index itself, whether he is an index investor, or is more activist as a portfolio manager. About five or ten percent of managers do beat the index each year, but they are general managers of small funds, and generally cannot repeat the performance consistently. It's a very useful message since the conclusion seems to follow that if a manager simply imitates the index, he will surely reduce his research costs, and will therefore almost surely have consistent final results which beat the average competitor. Ultimately, the best results will be found in long-term index funds with the lowest costs. That's a conclusion both logical and borne out by results; no amount of denial can refute the logic of it.

However, it is also possible to take it as a challenge. What approaches might be tested, to see if they can beat it? Mr. Bogle himself admits success might defeat a front-runner, by attracting so many investors the portfolio is forced to limit itself to large-size when the supply of frisky small stocks gets used up. If the small newcomers out-perform the blue chips, average big-fund performance will suffer by comparison with small boutique funds. Indeed, small-fund indices often display a 2% outperformance, compared with large-cap indices. It would probably be useful to consider closing a large fund to new purchases when the average size of its investment is forced to contract downward. Since such a reaction benefits the investors but not the managers, the right to close or reopen funds should be transferred to the shareholder investors.

|

| Common Sense on Mutual Funds |

New Tools. It is common for mutual funds to limit or forbid short-selling, as well as buying on margin. That's obviously less risky than engaging in such activity, but most investors understand greater returns require greater risk. That seems to be the approach adopted by hedge funds, although the success of it is often shrouded in secrecy for good reason, and has nothing in common with other stockmarket talents like demanding high fees. The main limitation on hedge fund competition comes from the excessive fees (2% annually, regardless of profits, plus 20% of profits themselves, and a five-year lock-in.) In effect, such activities can be simulated by funds controlled by a single university or pension fund. A fund with a large float of incoming deposits can treat the float as a virtual loan, and an organization which needs to mortgage a large construction project can treat the construction loan on the building as a virtual mortgage on the stock portfolio. It might further be argued that other organizations without a stock portfolio are overweighted in fixed assets whenever they take out a mortgage. Closed-end investment trusts seldom leverage overtly, but they usually are sold at a 10-20% discount to net asset value, and thus are effectively leveraged. Warren Buffett, the greatest stock market manager in history, owes much of his success to buying an auto insurance company outright and then using its float from premium deposits as if they were part of his portfolio. He tends to buy entire companies; their dividends disappear. In special circumstances with 1% prevailing interest rates, it can be difficult to make the case that borrowing is too risky for long-term investments; the issue now is liquidity.

And one final warning. When too many people get overleveraged, by whatever method, they generally sense the approaching dangers but often are restrained from selling by the tax consequences they would experience. But when it looks as though everybody sees the same thing, there may be a rush for the door. It's called a crash. So don't you dare buy on margin? Let me do it, and together we'll blame the speculators.

REFERENCES

| Common Sense on Mutual Funds: Fully Updated 10th Anniversary Edition: John C. Bogle ISBN: 978-0470138137 | Amazon |

New Looks for College?

|

| Kevin Carey |

The New York Times ran an article by Kevin Carey on March 8, 2015, predicting such big changes ahead for colleges, bringing an end of college as we know it. A flurry of reader responses followed on March 15, making different predictions. Since almost none of them mentioned the changes I would predict, I now offer my opinion.

|

| Cambridge University |

Colleges have responded to their current popularity, mostly by building student housing and entertainment upgrades, presumably to attract even more students. What I am seeing seems to be a way of taking advantage of current low-interest rates with the type of construction which can hope for conventional mortgages or even sales protection, in the event of a future economic slump. In addition, they are admitting many more students from foreign countries, probably hoping not to lower their standards for domestic admissions. They probably hope to establish a following in the upper class of these countries, eventually enabling them to maintain expanded enrollments by lowering standards for a worldwide audience of students, rather than merely a domestic one. With luck, that might lead to an image of superiority for American colleges, even after the foreign nations eventually build up their standards. The example would be that of Ivy League colleges sending future Texas millionaires back to Texas, which now maintains an aura of superiority for Ivy League colleges, well after the time when competing Texas colleges are themselves well-funded. The Ivy League may even be aware of the time when the Labor Party was in power in England, and for populist reasons deliberately underfunded Oxford and Cambridge. American students kept arriving anyway, seeking prestige rather than scholarship.

|

| William F. Buckley Jr |

Television courses seem to be a different phenomenon. A good course is a hard course, so a superior television course will prove to be even harder. In fact, it might be said the main purpose of college is to teach students how to study; the graduates of first-rate private schools find college to be rather easy, providing them with extra time for extra-curricular activities which are not invariably trivial. I well remember William F. Buckley Jr, pouring out amazing amounts of written prose for the college newspaper and other outlets, in spite of carrying a rigorous academic workload. I feel sure he did not acquire that talent in college, but rather, came to Yale, already loaded for Bear. I am certain I do not know what future place tape-recorded classes will eventually assume, but I do feel such courses would be most useful for graduate students, who have already learned how to study in solitude.

To return to the excess of dormitories under construction, the approaching surplus of them might also lead to better use, which is for faculty housing and usage. An eviction of students from dormitories would lead to urban universities beginning to resemble London's Inns of Court in physical appearance, with commuting day-students, mostly attending from nearby. The day is past, although the students do not believe it, that there is very much difference between living in Boston and living in California, and the much-touted virtue of seeing a new environment will eventually lose its charm. It may all depend on how severely a decline in economics retards the traditional pressure to escape parental control, but at least it is possible to foresee at least one improvement which could result from fiscal stringency.

Net Neutrality

|

| Bob Fernandez |

Bob Fernandez, a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer since 1993, recently addressed the Right Angle Club about Net Neutrality. He certainly knows his stuff about technology, but he got blind-sided, this time about politics. The term "net neutrality" is bewildering to most of us, and somehow it always had a ring of phoniness to it, as though it had been professionally synthesized by a corporate PR officer. And curiously, it seems to have much less interest to women, while it brightens up the eyes of almost any male audience. Men all have an opinion about it, even though the opinions differ from each other. Our speaker clarified this matter somewhat, by explaining that Netflix and Comcast have been dueling over this for several years. For one thing, Netflix consumes 40% of the bandwidth capacity of cable television.

In the commercial world, such a market dominance usually leads to the attitude by the customer (Netflix, in this case) that if they provide such a large amount of business, they are entitled to a volume discount. The seller, on the other hand, tends to feel that such a customer always wants special treatment so they can demand an extra-high price. The rest of the technical discussion is usually just special pleading, having to do with bandwidth, etc. The technical part was quite interesting since the field is constantly changing, but it wasn't what they were really arguing about.

|

| Net Neutrality |

The next day's Wall Street Journal ran a commentary from the Republican member of the Federal Communications Commission, declaring technology had nothing to do with it. President Obama had instructed the Democratic majority of the commission to make cable television into a regulated utility, and Chairman Wheeler had complied. In an instant, the issue was no longer technical, but a Constitutional issue of whether the President has a right to over-rule an "independent" commission in its judgment of a technical issue. Since the Constitution never mentions Independent Commissions, it could become quite a tangled issue.

The Wall Street Journal also had a side commentary of its own. Quite a normal political squeeze job. Congress and Presidents love to impose irritating regulations, for the sole purpose of shaking the money tree. That is, inducing both sides of a controversy to donate campaign funds, dragging it out for a few years, and then letting the corporations run their business as they please. My, my. Such a cynical public we are developing. Maybe what we need is an Evita Peron, to do this dirty work in a smoother way, so characteristic of the female sex.

Appealing the Constitution to a Higher Authority

|

| Justice Robert H. Jackson |

According to Justice Robert H. Jackson, "We" (The Supreme Court) "are not final because we are infallible, we are infallible because we are final." Scoop Jackson was the last Justice who never went to college or graduated from Law School, so his viewpoint concentrated on the practical outcome of a situation. In fact, the father of our constitution, James Madison, was learned in the history of many constitutions, and was well aware of allusions to divinity in the construction of our governing document, particularly when the sources of strong beliefs couldn't be grounded in evidence. However,the Age of Enlightenment was highly religious, so they gave credit to divine guidance when they really were imitating the Legal profession.The lawyer's system of progressive appeal to a hgher court of appeals was a very clever adaptation of recognition that most problems are pretty simple andcan be handled without much training.The Constitution is an attempt to reconcile our culture to the needs of government and the revelations of controversy. Composed by Enlightenment rationalists within a highly religious environment, the Founding Fathers were careful to use the metaphors of Religion, even though many were personally skeptics about the substance. Indeed, the Penman of the Constitution who ultimately wrote most of the words was Gouverneur Morris, a flagrant libertine. It had been the tradition of Constitutions to describe their culture by allusion to epic poems, drawing inferences about Right and Wrong from what had subsequently happened to ancient heroes after similar situations unfolded. Some would put the plays of Shakspere in that role in 1787, but the evidence is stronger for Roman writers, like Cato and Cicero. In my own view, this leap of faith was only divine in the sense it was a one-way street. A citizen might try to emulate the ancients, but appealing back to them was not likely to work.

Although the Constitution can be viewed as bridging a gap between Culture and Common Law, or perhaps as placing a guardhouse between them, this relationship is not spelled out and therefore, in theory, might be changed. Other cultures, perhaps the native Indian, or the Catholic Church of Central Europe, might be substituted, or other legal structures resembling the Napoleonic Code might serve on the opposite side of the bridge. These substitutions were a legal possibility, but there is little doubt the American leadership intended for an Anglo-Saxon culture, linked with Francis Bacon's legal system, to prevail under a distinctively American flag. Because of our debt to France for then-recent assistance, there was once the possibility of French coloration to our culture, but the excesses of the French Revolution soon ruled that out. Some modern observers have capsulized the scene: First, we got the British to help throw out the French in 1754; and then in 1776, we got the French to help us throw the British out. Both our allies thought we played their game, but we were playing our own. The new Constitution specified no laws, but with little doubt the Framers intended the states to adopt British Common Law without the infelicity of saying so.

|

| Bill of Rights |

And then there is the Bill of Rights. Madison had great faith in the ability of structure (separation of powers, term limits, etc.) to command predictable outcomes, and initially resisted any need for a Bill of Rights. But the Ratification Conventions in the states showed him the need to yield. The First Congress soon enough confronted over a hundred proposed rights in petitions from the states, especially the four big ones. If anyone else had been in Madison's position, our Bill of Rights would resemble the European one today, fifty pages long and growing. That outcome would have greatly weakened the Legislative branch since after protests about Mother Nature subside, the legal fact emerges that Rights are merely laws which no majority can overturn. They might even be characterized as a contrivance for transient majorities to promote the permanence of their viewpoint.

|

| The Founding Fathers |

But they are not the only contrivance in politics. Enshrinement of the Founding Fathers elevated their political positions into near divinity, whereas debunking the Founders personally undermines their symbolism as statues and myths. There was too much of this during the romance period of the Nineteenth century, but also in von Ranke's later marginalization of History into mere scholarship and footnotes, which was a reaction to it. The Founding Fathers themselves now supplant Achilles and Cincinnatus in our lexicon, and we have little choice but to accord more weight to their original intent in the Constitution, than to contemporary reasonings. Indeed, we are forced to acknowledge more similarity between George Washington's fictitious cherry tree than to his relations with Peggy Fairfax, when we interpret his thundering "Honesty is the best policy" in the second inaugural address. It is admittedly a difficult choice, but Justices now need to consider what his audience widely believed was his original intent, more than what later archeological discoveries uncover. Justice Scalia is correct in placing more weight on the original intent of the Founding Fathers than contemporary reactions to the same words. But in occasional conflicts between myth and reality, it seems safer to consider what the audience then widely believed, than what modern audiences would guess at.

Millennials: The New Romantics?

|

| Romantic Era |

It was taught to me as a compliant teenager that the Enlightenment period (Ben Franklin, Voltaire, etc.) was followed by the Romantic period of, say, Shelley and Byron. Somehow, the idea was also conveyed that Romantic was better. Curiously, it took a luxury cruise on the Mediterranean to make me question the whole thing.

It has become the custom for college alumni groups to organize vacation tours of various sorts, with a professor from Old Siwash as the entertainment. In time, two or three colleges got together to share expenses and fill up vacancies, and the joint entertainment was enhanced with the concept of "Our professor is a better lecturer than your professor", which is a light-hearted variation of gladiator duels, analogous to putting two lions in a den of Daniels. In the case I am describing, the Harvard professor was talking about the Romantic era as we sailed past the trysting grounds of Chopin and George Sand. Accompanied by unlimited free cocktails, the scene seemed very pleasant, indeed.

|

| Daniel Defoe |

In the seventy years since I last attended a lecture on such a serious subject, it appears the driving force behind Romanticism is no longer Rousseau, but Daniel Defoe. Robinson Crusoe on the desert island is the role model. Unfortunately for the argument, a quick look at Google assures me Defoe lived from 1660 to 1730, was a spy among other things, and wrote the book which was to help define the modern novel, for religious reasons. His personal history is not terribly attractive, involving debt and questionable business practices, and his prolific writings were sometimes on both sides of an issue. He is said to have died while hiding from creditors. Although his real-life model Alexander Selkirk only spent four years on the island, Defoe has Crusoe totally alone on the island for more than twenty years before the fateful day when he discovers Friday's footprint in the sand.

|

| Robinson Crusoe |

But the main point of history was that Defoe was born well before William Penn and died before George Washington was born. The romanticism he did much to promote was created at least as early as the beginning of the Enlightenment and certainly could not have been a retrospective reaction to it. Making allowance for the slow communication of that time, it seems much more plausible to say the Enlightenment and the Romantic Periods were simultaneous reactions to the same scientific upheavals of the time. Some people like Franklin embraced the discoveries of science, and other people were baffled to find their belief systems challenged by science. While some romantics like Campbell's Gertrude of Pennsylvania, who is depicted as lying on the ocean beaches of Pennsylvania watching the flamingos fly overhead, were merely ignorant, the majority seemed to react to the scientific revolution as too baffling to argue with. Their reasoning behind clinging to challenged premises was of the nature of claiming unsullied purity. Avoidance of the incomprehensible reasonings of science leads to the "noble savage" idea, where the untutored innocent, young and unlearned, is justified to contest the credentialed scientist as an equal.

Does that sound like a millennial to anyone else?

Passive Investing

|

|

| Roger Ibbotson |

Roger Ibbotson compiled the results of investing in the past hundred years and divided it into different aggregate classes of investments -- large capitalization common stock, small capitalization stock, bonds, and whatnot. It happens that Burton Malkiel showed that such aggregates outperformed most mutual funds with the same goals, and John Bogle of Vanguard showed that index funds of such asset classes also outperformed stock-picker managed mutual funds, mostly because of lower costs.

|

| Burton Malkiel |

The eliminated costs included the cost of stock-pickers, who are often highly compensated, sales costs, and transaction taxes from frequent turn-over. He invented the term "passive investing" for the purchase of index funds rather than individual stocks, and it's easily understood why index funds would have lower costs than managed portfolios. Mr. Bogle's index funds in the Vanguard Group have an annual transaction cost of less than a tenth of a percent, while it is not uncommon for managed funds of common stocks to charge $250 or more, per trade. In a few years, index funds have grown to be half of the market, giving direct stock investing a very hard time of it. Buy them, hold them through thick and thin, and scarcely ever sell them. The consequence is that passive investing of this sort returns two or more percent more to the investor.

|

| Vanguard Group |

Multiplied by the compound income principles mentioned earlier, passive investing is pretty well sweeping the Health Savings Account field. In fact, most managers of HSA are having a difficult time deciding how to charge for other necessary services, like debit card management, sales, transactions, and advice. The most conservative of all small-investor vehicles, like money-market funds, bank certificates of deposit, and other savings vehicles, are currently suffering from such low-interest rates that even they are being abandoned. In the peculiar financial environment of the present time, investors who shunned stock purchases as "gambling", find they have almost no other choice for their Health Savings Accounts. Investment management firms who depended on non-stock investments, are simply driven out of business if they don't switch to passive investments.

|

| John Bogle |

That's really all there is to say about passive investments for Health Savings Accounts, except to say it should be a good thing. Common stocks have out-performed just about everything else for a century. The small investor tends to be afraid of them because of the "black swan" crashes of 2008 and 1929, which students of the subject tell us to occur about once every thirty years. We, therefore, should take a moment to address this problem, because various reactions to it, can have a very large effect on something the investor should be watching carefully, the percentage return on his investments. Multiplied by the compound interest effect of longevity, this is really the key to whether the HSA will be effective in lowering healthcare costs.

Pickett's Charge

|

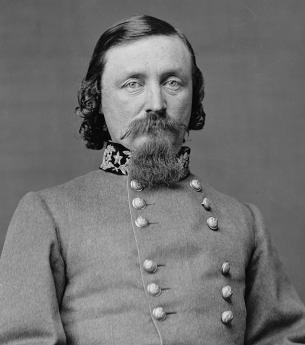

| General George Pickett |

If you want to baffle a Philadelphian, just stop him and ask who defeated Pickett's Charge at the battle of Gettysburg. Like the Charge of the Light Brigade, everybody knows who the losers were, but nobody seems to know who won the battle. After all, history is usually written by the victor.

Well, in fact, the battle was won by 13,000 Union troops stationed at the Bloody Angle, only two soldiers deep behind a stone wall, to defend against 60,000 Confederate troops who had been concentrated by Pickett to converge on that point of defense. The whole Union army of about 60,000 men had been strung out along a farmland ridge, uncertain at what point Pickett would concentrate. At a little copse of trees at the angle of two stone walls, were three Philadelphia brigades, composed of Philadelphia blueblood officers and soldier volunteers drawn from Irish volunteer firemen, recruited by members of the Union League of Philadelphia. These Philadelphians, both officers, and men were to suffer 50% mortality in an hour of fighting. At one point they started to break and run when 150 confederate cannon were concentrated on their position, then rallied and held their ground when it was the Confederate turn to break and run for home.

|

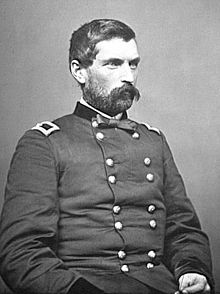

| General John Oliver Gibbon |

Although General John Gibbon was the highest ranking Philadelphian in charge, and Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb was a New Yorker who had been in command of the three brigades for only one day, winning the Congressional Medal of Honor, the real hero was Lieutenant Frank Haskell. Seeing the Union defenders starting to break, Haskell rode his white horse outside the wall ahead of his troops and suddenly ordered them to turn and fire at the hesitating Union troops. The shock of this maneuver stopped the retreat, turned the troops to face Pickett's onrushing men, and routed the Southern advance after Confederate General Armistead vaulted the wall and started to attack the defenders in hand to hand combat. A member named Haskell was in the audience when Author Bruce Mowday told this story to the Right Angle Club, but Robert Haskell never uttered a word.

|

| Bruce Mowday |

Since this incident, I have repeated the story to dozens of Philadelphians, and not one was even faintly aware of it. It reminded me of Digby Baltzell's book Boston Puritans and Philadelphia Quakers , which expresses Baltzell's opinion that Quaker reticence is the source of Philadelphia's academic and political decline. My own opinion takes a different view of the distinctiveness of Philadelphia modesty, which was contrasted with New England by John Adams' remark that "In Boston, every goose is a swan."

When you run your eye down the list of Philadelphia Union officers who fought in this crucial battle, there is only one recognizably Quaker name from a city which even at the time of the Civil War was still Quaker-dominated. Quakers had been urged by the London Yearly Meeting to withdraw from the war tax issues of the French and Indian, and Revolutionary Wars, but a great many Quakers had fought against the British, anyway. By the time of the Civil War, however, the antiwar Quaker position had considerably strengthened. I can still remember Henry Cadbury reciting the position of his mother, a satire of the Battle Hymn of the Republic: "He died to make men holy, we will kill to make men free." The Civil War had greatly strengthened antiwar sympathies in the North, especially in Quaker Philadelphia.

|

| Revolutionary War |

Consequently, when the spoils of war were handed out, public opinion demanded that the heroes of Gettysburg be rewarded, without drawing any openly negative opinions about those who declined to serve. After all, the Quakers had initiated and led the battle to free the slaves and shared a certain amount of wide-spread sympathy with the idea that the Southern states were entitled to secede if they wanted to. And Quakers at the time retained considerable wealth and the power to defend themselves, if attacked, not to mention wide-spread ambivalence about the War. So, there was no great effort to persecute Quakers, but the idea of sharing the spoils of war with them was just a little too much. Six hundred thousand soldiers had been killed in that war, and although Gettysburg contributed 51,000 of them, it was far from being the only bloody battle. It is my suspicion the constant decline of Quaker influence in Philadelphia since the Civil War, can largely be traced to unpleasant echoes of this more or less inevitable response to a postwar commonplace.

|

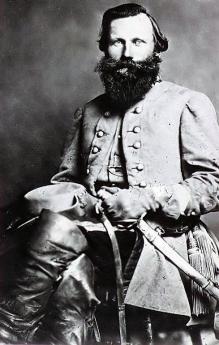

| General JEB Stuart |

It is unfair to bring up the subject of the battle at Gettysburg, without mentioning three other factors which historians cite as causes of the defeat of Generals Lee and Pickett. In the first place, the rather inferior Confederate artillery consistently overshot the target of the front line of Union troops and fell harmlessly in their rear. Lots of noise, not much damage. It is also true Confederate General JEB Stuart was planned to attack the Union lines from the rear, but was delayed by attacks of troops under the command of, might you know it, General Custer. And finally, as Pickett himself remarked, "The Union Army probably had something to do with it."

REFERENCES

| Pickett's Charge: The Untold Story. Author: Bruce E. Mowday ISBN:978-1-56980-4 | Amazon |

Septa's Brain Center

|

| Septa System Map |

The Right Angle Club was recently introduced to two important examples of the Philadelphia Scene. The old spirit we used to have so much of, capsulized by the expression, "Pick up the ball -- and run with it!". It was very heartening to behold.