0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Philadelphia's Fourth Century: Revival or Relapse?

Novelists, sociologists, playwrights, financiers, historians, poets -- and others -- have described and explained the rise and fall of Philadelphia. Each of them is a little bit right, and a little wrong. Philadelphia is hidden, but it isn't hiding.

Decline and Fall of Philadelphia

|

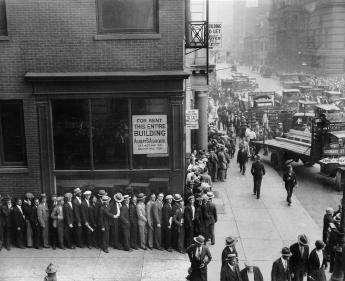

| 1929 Crash |

We talk high finance here, so perhaps a simple story from Wall Street is needed to introduce the topic to a non-Wall Street audience. Following the 1929 crash, and consequent to the Glass Steagall Act, Morgan Stanley was the only American investment bank in existence. It was the first of a new kind, but barely in existence, doing something like $300,000 worth of business in 1933. As finance adjusted to the new ground rules, Morgan Stanley grew in size, commonly referred to as the "White Shoe" investment bank. That term was an allusion to the Ivy League background of its partners, who came from colleges which affected white buckskin shoes among their more elite students. It also referred to the fact that almost all Morgan Stanley partners were pretty rich and fairly young, entirely able to live by a code of behavior which might be summarized as, "We don't find it necessary to cheat."

Buried within that motto was the idea that Morgan Stanley was as good as its word, and tried very hard to avoid doing business with anybody who did cheat. In a business where a great deal of business was transacted too quickly for written contracts or vetting by law firms, that meant a lot.

<Morgan Stanley soon climbed to the top of a very tough heap and stayed there for fifty years. Many of its partners were millionaires in their twenties, but so what, they were mostly pretty rich before they joined the firm. The company ran as a partnership, with the capital they leveraged coming from the personal fortunes of the partners. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising many partners retired in their forties, taking their enhanced capital with them. The Glass-Steagall Act (now being imitated by the Volcker Rule within the Dodd-Frank Law) made it illegal for a depository bank to be under the same roof with an investment bank. Much of the capital in the pre-1929 days had been supplied by the deposits in the depository bank, but Glass Steagall cut that off when it created depository insurance, on the theory that deposit insurance was a Federal gift, and its "moral hazard" should not flow through to the speculation of investment banking.

That comment was tinged with populism, with the dubious implication that those who are two generations off the farm are less likely to cheat than those who are five generations off the farm. So the depository bank of Morgan Guaranty has split away from the investment bank of Morgan Stanley, which was the three-step process by which Morgan Stanley eventually grew so big it could no longer be sustained by leveraging the personal wealth of its partners.

|

| Buy And Sell |

Eventually, the pressure to raise money by selling stock to the public could no longer be resisted. The rich partners became even richer by selling their company's stock on the stock exchange, the company did grow enormously, and a lot of new stockholders got rich, too. Unfortunately, when you sell a stock you also sell voting rights, so the sale transferred voting control of the company to the new stock purchasers. It did not take many years before the white shoe atmosphere was a thing of the past, along with the discipline that the atmosphere imposed on the rest of corporate America. When the 2008 crash came along, there was enough questionable behavior on Wall Street to justify a populist President of the United States to tolerate, or even encourage, a witch hunt of Wall Street bankers for ruining the country.

Even so brilliant an economist as Paul Volcker has encouraged the idea that separating the two forms of banks was an unmitigated blessing which must be restored, while in fact it is only justified by the gift of Federal Deposit Insurance to the depository arm, not the Investment Banking Arm. It seems only a matter of time before there will be agitation to extend the insurance to the investment arm so we will be chasing our own tail, of extending insurance to encourage risk-taking, instead of using demand deposits to do so. And thus inviting another crash.

I'm sorry, Paul, but there is a reversed way to describe it. The small investors demanded the entitlement of risk-free investing, protected by deposit insurance. And they declared this insurance was a special entitlement to which wealthy players were ineligible. When small punters go broke, it is a tragedy. When big players go broke, it serves them right for being so greedy.

|

| Gasoline |

Converting partnership or family businesses into stockholder organizations was a universal outcome of both World Wars, all over the world. The phenomenon can be looked at as one way of extracting frozen wealth to pay war debts. It is accompanied by an increase in national indebtedness, so it makes civilizations less stable. Scraps of partnership control do continue to persist in remote developing countries, and in tiny principalities like Luxembourg, but it seems only a matter of time before the public buys them out. The only major developed country to retain family control of businesses in Germany. Apparently, it was intentional, based on the inheritance laws. Tightly held countries are more commonly tightly held together by force, as in Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Monaco, usually because of a monopoly grip on oil or other natural resources. But even those governments could probably be toppled, except for fear of ensuing chaos, just as did happen to many former dictatorships, and was a source of fear in Philadelphia. A case can be made for populism if it is kept small and under control. Hardly any case at all can be made for chaos.

|

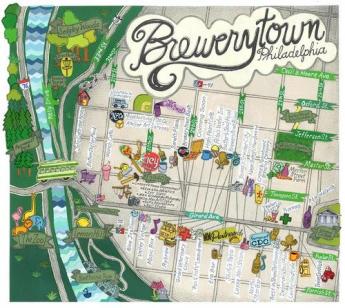

| Brewerytown Map |

For those of us who love Philadelphia and wonder what happened to it, let me point out three defining local peculiarities. Prohibition was more of a factor than we like to think because Philadelphia's Tenderloin was the former Brewerytown, filled with Beer Gardens, refrigeration plants (Lager beer is brewed in the cold) and beer distributors. The passage of the Volstead Act suddenly transformed the largest alcohol-production center in the country into the largest alcohol-consuming area, from River to River, from Franklin Square to the Schuylkill.

It was concentrated in the Brewerytown by being illegal, and somewhat secret. Brewerytown soon turned into the Tenderloin, and the Tenderloin into Skid Row, cutting off North Philadelphia from law and order, but in time it was alarming in a different way to see speakeasies spread into other sections of the city. Much as it tried, even the Mafia couldn't control the influx of amateur criminals, when the Tenderloin essentially cut the city in half.

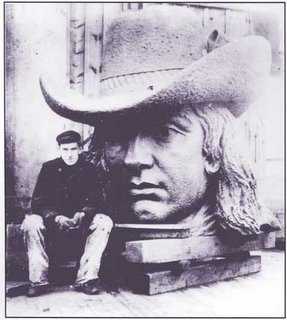

When the great migration from the South occurred after WW II, the immigrants turned North Philadelphia into a slum. Cutting I76 along the same center-city lines helped shrivel North Philadelphia and hustle its flight to the suburbs. Some misadventures of Philco and Ford, Baldwin and Stetson hastened the process and may have caused some of it.

|

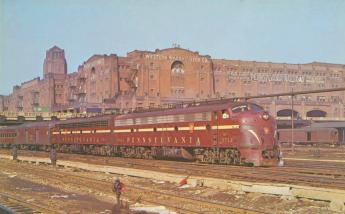

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

America grew into a mighty industrial nation as a result of becoming the Arsenal of Freedom in the Civil War and two World Wars. The nation needed to expand its industrial base from the essential monopoly corridor of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and it had the money to do so. The land was cheaper elsewhere, labor was nonunion elsewhere, and air conditioning made the South bearable. Wall Street saw an enormous opportunity to buy stock from the family partners of Philadelphia industries, and sell it again to the world. These new owners had no interest in preserving lovable Philadelphia; they wanted to reap the harvest of expanding what we had, to the rest of the country, maybe even the rest of the world.

Once a spiral like this gets started, it runs by itself. The owners of the mansions on the hills, proprietors of what were big businesses by Victorian standards, sold their partnerships, their children were converted into coupon clippers, and their grandchildren into trust-fund babies. If you really have nothing much to do, why not do it in California next to the beaches? Hollywood made trust fund babies seem glamorous on the Main Line, just as Madison Avenue had once made patriots on the left bank seem fatally attractive. Those movies and novels made somebody pretty rich, but whoever it was, doesn't live here, anymore.

Philadelphia City-County Consolidation of 1854

|

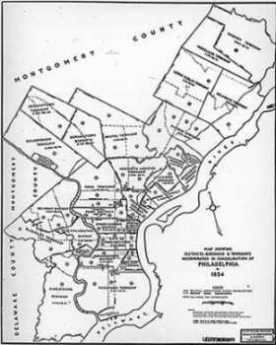

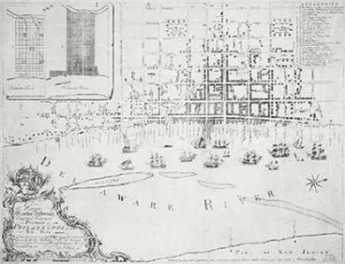

| Consolidation Map 1854 |

Philadelphia is still referred to as a city of neighborhoods. Prior to 1854, most of those neighborhoods were towns, boroughs, and townships, until the Act of City-County Consolidation merged them all into a countywide city. It was a time of tumultuous growth, with the city population growing from 120,000 to over 500,000 between the 1850 and 1860 census. There can be little doubt that disorderly growth was disruptive for both local loyalties and the ability of the small jurisdictions to cope with their problems, making consolidation politically much more achievable. A century later, there were still two hundred farms left in the county which was otherwise completely urbanized and industrialized. For seventy-five years, Philadelphia had the only major urban Republican political machine. By 1900 (and by using some carefully chosen definitions) it was possible to claim that Philadelphia was the richest city in the world, although this dizzy growth came to an abrupt end with the 1929 stock market crash, and the population of Philadelphia now shrinks every year. In answering the question of whether consolidation with the suburbs was a good thing or a bad thing, it was clearly a good thing. But since Philadelphia is suffering from decline, it becomes legitimate to ask whether its political boundaries might now be too large.

|

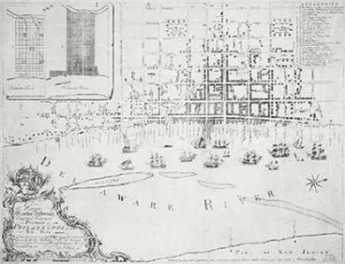

| Philadelphia Map 1762 |

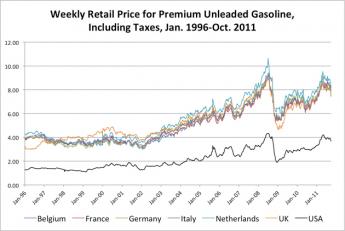

The possible legitimacy of this suggestion is easily demonstrated by a train trip from New York to Washington. The borders of the city on both the north and the south are quickly noticed out the train window, as the place where prosperity ends and slums abruptly begin. In 1854 it was just the other way around, just as is still the case in many European cities like Paris and Madrid. But as the train gets closer to the station in the center of the city, it can also be noticed that the slums of the decaying city do not spread out from a rotten core. Center City reappears as a shining city on a hill, surrounded by a wide band of decay. The dynamic thrusting city once grew out to its political border, and then when population shrank, left a wide ring of abandonment. It had outgrown its blood supply. Prohibitively high gasoline taxes in Europe inhibit the American phenomenon of commuter suburbs. The economic advantage of cheap land overcomes the cost of building high-rise apartments upward, but there is some level of gasoline taxation which overcomes that advantage. Without meaning to impute duplicitous motives to anyone, it really is another legitimate question whether some current "green" environmental concerns might have some urban-suburban real estate competition mixed with concern about global warming. Let's skip hurriedly past that inflammatory observation, however, because the thought before us is not whether to manipulate gas taxes, but whether it might be useful to help post-industrial cities by contracting their political borders.

Before reaching that conclusion, however, it seems worthwhile to clarify the post-industrial concept. America certainly does have a rust belt of dying cities once centered on "heavy" industry which has now largely migrated abroad to underdeveloped nations. But while it is true that our national balance of trade shows weakness trying to export as much as we import, it is not true at all that we manufacture less than we once did. Rather, manufacturing productivity has increased so substantially that we actually manufacture more goods, but we do it with less manpower and less pollution, too. The productivity revolution is even more advanced in agriculture, which once was the main activity of everyone, but now employs less than 2% of the working population. This is not a quibble or a digression; it is mentioned in order to forestall any idea that cities would resume outward physical growth if only we could manipulate tariffs or monetary exchange rates or elect more protectionist politicians to Congress. Projecting demographics and economics into the far future, the physical diameters of most American cities are unlikely to widen, more likely to shrink. If other cities repeat the Philadelphia pattern, the vacant land for easy exploitation lies in the ruined band of property within the present political boundaries of cities, or if you please, between the prosperous urban center and the prosperous suburban ring.

Many American cities with populations of about 500,000 do need more room to grow, so let them do it just as Philadelphia did a century ago, by annexing suburbs. But there are other cities which have lost at least 500,000 population and thus have available low-cost low-tax land which would mostly enhance the neighborhood if existing structures were leveled to the ground. Curiously, both the shrunken urban core and the bumptious thriving suburbs could compete better for redeveloping this urban desert if the obstacles, mostly political and emotional, of the political boundary, could be more easily modified. But that's also just a political problem, and not necessarily an unsolvable one.

Aftermath: Who Won, the States or the Federal?

|

| Thirteen Sovereign States |

In the case of the American Constitution, the initial problem was to induce thirteen sovereign states to surrender their hard-won independence to a voluntary union, without excessive discord. Once the summary document was ratified by the states, designing a host of transition steps became the foremost next problem. The dominant need at that moment was to prevent a victory massacre. The new Union must not humble once-sovereign states into becoming mere minorities, as Montesquieu had predicted was the fate of Republics which grew too large. Nor must the states regret and then revoke their union as Madison feared after he had been forced to agree to so many compromises. As history unfolded, America soon endured several decades of romantic near-anarchy, followed by a Civil War, two World Wars, many economic and monetary upheavals, and eventually the unknown perils of globalization. When we finally looked around, we found our Constitution had survived two centuries, while everyone else's Republic lasted less than a decade. Some of its many flaws were anticipated by wise debate, others were only corrected when they started to cause trouble. Still, many tolerable flaws were never corrected.

Great innovations command attention to their theory, but final judgments rest on the outcome.

|

| . |

Benjamin Franklin advised we leave some of the details to later generations, but one might think there are permissible limits to vagueness. The Constitution says very little about the Presidency and the Judicial Branch, nothing at all about the Federal Reserve, or the bureaucracy which has since grown to astounding size in all three branches. Political parties, gerrymandering, and immigration. Of course, the Constitution also says nothing about health care or computers or the environment; perhaps it shouldn't. Or perhaps an unmentioned difficult topic is better than a misguided one. Gouverneur Morris, who actually edited the language of the Constitution, denounced it utterly during the War of 1812 and probably was already feeling uncomfortable when he refused to participate in The Federalist Papers . Madison's two best friends, John Randolph, and George Mason, attended the Convention but refused to sign its conclusions, as Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson almost certainly would also have done. On the other hand, Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris came to the Convention preferring a King to a President, but in time became enthusiasts for a republic. Just where John Dickinson stood, is very hard to say. Those who wrote the Constitution often showed less veneration for its theory, than subsequent generations have expressed for its results. Understanding very little of why the Constitution works, modern Americans are content that it does so, and are fiercely reluctant about changes. The European Union is now similarly inflexible about the Peace of Westphalia (1648), suggesting that innovative Constitutions may merely amount to courageous anticipations of radically changed circumstances.

|

| President Franklin Roosevelt |

One cornerstone of the Constitution illustrates the main point. After agreeing on the separation of powers, the Convention further agreed that each separated branch must be able to defend itself. In the case of the states, their power must be carefully reduced, then someone must recognize when to stop. If the states did it themselves, it would be ideal. Therefore, after removing a few powers for exclusive use by the national government, the distinctive features of neighboring states were left to competition between them. More distant states, acting in Congress but motivated to avoid decisions which might end up cramping their own style, could set the limits. The delicate balance of separated powers was severely upset in 1937 by President Franklin Roosevelt, whose Court-packing proposal was a power play to transfer control of commerce from the states to the Executive Branch. In spite of his winning a landslide electoral victory a few months earlier, Roosevelt was humiliated and severely rebuked by the overwhelming refusal of Congress to support him in this judicial matter. The proposal to permit him to add more U.S. Supreme Court justices, one by one until he achieved a majority, was never heard again.

|

| Taxes Disproportionately |

Although some of the same issues were raised by the Obama Presidency seventy years later, other more serious issues about the regulation of interstate commerce have been slowly growing for over a century. Enforcement of rough uniformity between the states rests on the ability of citizens to move their state of residence. If a state raises its taxes disproportionately or changes its regulation to the dissatisfaction of its residents, the affected residents head toward a more benign state. However, this threat was established in a day when it required a citizen to feel so aggrieved, he might angrily sell his farm and move his family in wagons to a distant region. People who felt as strongly as that was usually motivated by feelings of religious persecution since otherwise waiting a year or two for a new election might provide a more practical remedy. However, spanning the nation by railroads in the 19th Century was followed by trucks and autos in the 20th, and then the jet airplane. While moving residence to a different state is still not a trivial decision, it is now far more easily accomplished than in the day of James Madison. A large proportion of the American population can change states in less than an hour if they must, in spite of a myriad of entanglements like driver's licenses, school enrollments, and employment contracts. The upshot of this reduction in the transportation penalty is to diminish the power of states to tax and regulate as they please. States rights are weaker since the states have less popular mandate to resist federal control. It only remains for some state grievance to become great enough to test the present power balance; we will then be able to see how far we have come.

|

| High Gasoline Taxes of Europe |

Since it was primarily the automobile which challenged states rights and states powers, it is natural to suppose some state politicians have already pondered what to do about the auto. The extraordinarily high gasoline taxes of Europe have been explained away for a century as an effort to reduce state expenditures for highways. But they might easily be motivated by a wish to retard invading armies or to restrain import imbalances without rude diplomatic conversations. But they also might, might possibly, respond to legislative hostility to the automobile, with its unwelcome threat to hanging on to local populations, banking reserves, and political power.

It helps to remember the British colonies of North America were once a maritime coastal settlement. The thirteen original states had only recently been coastal provinces, well aware of obstructions to trade which nations impose on each other. Consequently, they could readily design effective restraints to mercantilism within the new Union. Two centuries later, repeated interstate quarrels provided fresh viewpoints on old international problems. As globalization currently becomes the central revolution in trade affairs of a changing world, America is no beginner in managing the intrigues of international commerce. Or to conciliating nation states, formerly well served by nation-state principles of the Treaty of Westphalia, but this makes them all the more reluctant to give some of them up.

An Industrial Nation, or a Plantation Society?

There is a phrase much used in diplomacy and politics, sometimes attributed to Lord Palmerston, sometimes to Cicero.

In politics, there are no permanent friends, no permanent enemies, only accommodations.

Regardless of who coined the adage, it is difficult to imagine either stone-faced George Washington listening with any approval, or politician James Madison displaying the least surprise. The only American scholar of politics and political history available to Washington, Madison eventually evolved into a total politician. The evolution in the underlying core beliefs of these two men, in opposite directions, seems to explain the slow transformation of their Virginia plantation friendship into outright hostility. On one level, their disagreements may be seen as responses to their new roles: Washington created and molded the executive department, and while he helped him do it, Madison himself migrated into the role of leader of Congress. Once there, he was not strong enough to escape the collective power of Congress to mold its leaders into servants, a situation that was not corrected until Henry Clay over-corrected it in the opposite direction. On another level, it is possible to view the two Virginians as having different reactions to the oncoming Industrial Revolution.

Although both were Virginia plantation owners, General Washington's wartime experience was that his own solitary opinion, right or wrong, would ultimately be all that mattered. All that advice he got was simply information-gathering. On the other hand, while the leader of the legislative branch was often able to change legislative opinion, he would be ultimately forced to accept the collective opinion of Congress or resign his leadership of it. That was also true of the Chief Executive Officer, but several steps removed from Congressional decisions, and of the opinion, he must finally accept their final wishes if they seemed to represent the will of the people who voted them into office. Of the two, he was better able to understand what Hamilton was talking about, better able to appreciate that the strength of a nation has an economic base as well as a military one. The mythology of the era has Alexander Hamilton in combat with James Madison, with Washington in the middle but eventually siding with Hamilton. That's true enough, but the greater truth is that these individuals were cast as the symbols of the changing beliefs of the country. It must be conjectured the high adventure of creating a new form of government held the three together, even as many things turned out to be unanticipated. Washington seems more dismayed by gradually perceiving some unwelcome imperatives of the Constitution, while Madison simply set about to make the most of them. Washington believed in character, a personality based on steadfastness, courage, and determination. Adaptability, yes, pliability, no.

|

| James Madison |

The official organizing principle of every legislature, Congress, or parliament is that each member has one vote and therefore is the equal of every other member. Washington understood leaders would emerge, able to persuade others. What he did not anticipate was that some would scheme to acquire the power to compel obedience. Unofficial ways to acquire power over colleagues differ among legislatures but have certain recurring features.

Vote-swapping.

|

The press of business usually requires a division of labor into committees, who soon acquire special expertise. A chairman is selected to handle routine matters, and to negotiate compromises with overlapping committees; the chairman acquires power. Members differ in their degree of interest in almost any topic; those who have little interest in a particular outcome have an opportunity to trade their vote for assistance on some other matter of much greater concern to them; why not? From this evolves the strategy of striving to discover what each voter secretly wants most of all; offering assistance on that favorite topic is the first step in enlisting later support on some other issue. If he wants your help badly enough, he may even vote against something else he really favors. If he wants to be chairman of a committee important to his interest, it may even be possible to force him to vote for something he privately hates. Vote-swapping is the fundamental currency of legislative trading, and it is sometimes a loathsome business. But just try to imagine George Washington swapping votes to become chairman of a committee, or to enact an appropriation; it couldn't happen.

One suspects it did happen, at least once. Washington badly wanted the nation's capital to be across the Potomac River from his plantation. Indeed, he wanted the Potomac River to be the main commercial highway of the nation to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi. He never said he wanted the nation's capital to be named after him, but he did not object a great deal, either. When there was quibbling about the location of the White House, the old surveyor went there himself and laid it out with a surveyor's transit. Washington wanted Virginia to be the biggest most important state in the union; four of the first five presidents were Virginians. And so, when Hamilton and Jefferson negotiated the Compromise of 1790, everyone knew what Washington's feelings were. The revolutionary debts of Virginia became federal debts, in return for relocating the capital from the banks of Delaware to the banks of the Potomac. Robert Morris was fit to be tied. Washington stood aloof and uninvolved. Anyone who has ever been involved in one of these compromises knows that some participants see nothing wrong with it, while others hate themselves forever, for having had anything to do with it. In fact, the legislators most offended by vote-swapping are the ones who once somehow got unwillingly dragged into it, and never entirely forgave themselves. Natural politicians like Madison, however, are irked by those who criticize such a natural and effective process, whose successes are everywhere to be listed. While no one can read the minds of these two founding fathers, there seems little doubt they were on different sides of this enduring division in the personality types of people in public office and therefore headed for a collision whenever a sufficiently major issue arose.

The genius of the evolving American form of government was to leave land ownership in private hands while creating a new power center in banking and finance.

|

The issue was major, all right. It was the question of whether this proud new nation was going to join the Industrial Revolution, with all its smoke and crowding, greed and striving. Or whether it was going to sweep majestically along with the romantic movement of the day, the happy farmer and the noble savage, spreading out on a bountiful endless continent. To some extent, this was an echo of the French Revolution which so enthralled Madison's best friend Thomas Jefferson, drawing the conflict between England and France into our own rather recent revolution. Great Britain was a century ahead of France in the Industrial Revolution, which originated north of Manchester where William Penn's Quakers came from. Yes, factories were sort of polluting and crowded, certainly enough to get Marx and Engels excited. But there was another undeniable truth: England soon got richer, acquired a world empire, had a bigger navy, and was soon to beat Napoleon at Waterloo. It was rather easy to prove to George Washington that an economically stronger nation was likely to be militarily stronger as well. Eventually, the point would even be forcibly brought home to Robert E. Lee. American tourists in Europe today echo the sentiment when they chose a vacation itinerary: no churches, and no museums, please. But to be fair to the Virginians, the point was not at all obvious in 1790. Virginia owned what are now three states, and held significant claims to what is now five more. Why would Virginians have any interest in dirty factories or the grubby strivings of immigrant merchants?

Still another historical curiosity emerges from the twenty-five years of Philadelphia as the new nation's capital, which is really our national epic poem, waiting for its Homer to compose it. Just about everybody at the Convention agreed the national government had to be strengthened; the state legislatures were going to ruin us. Madison, representing the views of the landowner aristocracy, was also afraid the national government could get too strong and ruin them by disturbing private property ownership. Hamilton didn't care about the land, he cared about money; he wouldn't mind a King if one was necessary to get things done. It should be remembered that feudalism was largely based on the king's right to reassign land ownership in return for military support. The genius of the evolving American form of government was to leave land ownership in private hands while creating a new power center in banking and finance. So it eventually evolved that Madison and his friends from Appalachia wanted to limit the powers of the national government strictly to those few areas where we needed it strong; enumerated powers were the result. The Federalists following Hamilton stretched enumerated power as far as it would reach with extra "implied" powers, together with their "emanations and penumbras". If you were to defend the nation, you needed a navy; eventually, it would be implied you needed an air force, maybe atom bombs. Increasing Federalism was the driving force of the Republican Party down to the time of Franklin Roosevelt, indeed down to the moment when the Philadelphian Owen Roberts tipped the Supreme Court majority in favor of eliminating "the commerce clause". Since that time, the Republican descendants of Alexander Hamilton have sought to shrink and restrain federal powers and bureaucracy, while the political descendants of James Madison have sought to populate Virginia with civil servants up to and beyond Piedmont. Both Madison and Hamilton must be turning in the grave about the way this topic evolved. But the power being struggled for is all commercial power; ownership control of land remains off the political table. Perhaps the day will come when fresh land no longer seems unlimited, making monopoly control of it seem more threatening. More likely, the agricultural economy will nearly vanish, taking its power struggles along with it. The paradox emerges that increased productivity will likely shrivel the importance of manufacturing as well, leaving both farm and factory as relics of the past. The test of a constitution is how well it adapts to an unknown future.

Anatomy of an Urban Political Machine

|

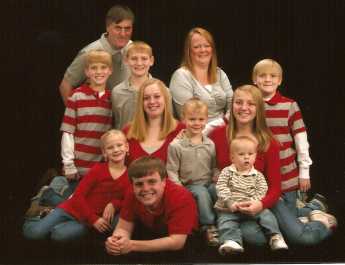

| One Big Family |

The Franklin Inn Club meets every Monday morning to discuss the news, and recently it discussed the upcoming local political campaign. The discussion went on for fifteen minutes before a newcomer asked if we were talking about the primary or the general election. The question was met with broad smiles all around because of course, we were talking about the primary. Voter registration is 6:1 in favor of the Democrats in Philadelphia, so the general election is just a required formality. The election, that is, consists only of the Democrat primary; election of the Democrat nominee in the general election is a foregone conclusion. Someone idly remarked on the number of politicians who are blood relatives of other politicians, someone else said that was true of union officers, too. So, skipping from the inside baseball of the election, we took a little time to discuss the anatomy of an urban political machine.

The first step in consolidating control of a city by a political machine is to eliminate the issue of the general election by making the other party's chances seem hopeless. That converts an election which typically turns out 40% of the voters into an exclusively primary election, turning out 20% of the voters, or even less in an off-year. In some "safe" districts a winner needs far less than 10% of the eligible voters to win.

The second step is to run as a prominent member of a local ethnic or religious group, preferably the largest of such groups within the district. If possible, an election is almost assured by being the sole candidate associated with the largest ethnic group. Here's where family connections work for you. If your father held the same seat, or some other family member had been prominent in the district, it helps assure everybody that you are really an ethnic member and not just someone whose name sounds as though it would be. Your relative will know who is important in locally local politics, the members of large families or people are known to be the "go-to guy".

Assembling all that, the final step is to get everyone else who is a member of the ethnic group to drop out of the primary, and to encourage other ethnic groups to field as many candidates as possible, splitting up their vote. Getting other members of your religious group to drop out, consists of having your relative approach them and tell them to wait their turn. The implicit promise underneath that advice is probably next to worthless, unless it is specific and witnessed, and the other fellow's ability to deliver it is credible. If all else fails, the resistant opponent is muscled in some way, verbally at first, and then increasingly threatening. The consequence of this ethnic/religious influence is more involvement in government by clergy than is healthy for either one of them. Now, that's about all there is to achieving permanent incumbency, but the minority party should be mentioned, as well as the flow of money.

It quite often happens that the minority party in the big city, hopeless in its own election chances, finds itself with a Governor and/or Legislature of their party. The patronage of state jobs becomes available to the foot soldiers who have no chance of local election. Much of the wrangling within state legislatures revolves around whether appointive patronage jobs should be lodged in state agencies, or local ones; at the moment, the Parking Authority and the Port Authorities figure prominently as jobs for which a local Republican could aspire. The coin of this trade is maintaining influence in the state nominating process and paying off with increased voter turn-out in elections which have no local effect but may be important at the state or national level. Since party dominance at state and national levels changes frequently, the local machine finds it useful to continue this system. Where they have nothing to lose in local elections, they may even encourage it.

Money is the mother's milk of politics. Except for safe districts no one can get elected without it. And various degrees of corruption provide money to be "spread around" the clubhouse, sometimes to induce people to drop out of primary races, sometimes to console "sacrifice" candidates who run hopeless campaigns just to make the party look good, and sometimes just to enrich the undeserving. The politically connected parts of the legal profession participate a good deal in the flow of funds, sometimes in order to get government legal work, sometimes to obtain judgeships, sometimes to launder the money for clients. One particularly lurid story circulates that professional sports teams are expected to make seven-figure contributions in return for lavish new stadium construction, from which they, in turn, are able to generate various sorts of compensating revenue.

But, as the old story goes, if you eat lunch with a tiger, the tiger eats last.

Ardrossan Wayne PA

Ardrossan, the home of the Montgomery family, covers two square miles of Main Line real estate.

Barbarians At the Gates of the Magical Kingdom

|

| Mickey Mouse |

The Walt Disney Corporation held its annual stockholder meeting on March 3, 2004, in Philadelphia's Convention Center. There were only five items of business: the re-election of directors (no names on the ballot in opposition), re-appointment of the auditors ( reappointed every year for twenty-eight previous years), and three stockholder proposals ( overwhelmingly defeated several times in the past). Typical stockholder meetings leisurely dispose of such an agenda in about twenty minutes. This one took seven hours.

There could well have been two unstated reasons for the protracted meeting. The first would be self-inflicted: direct advertising to thousands of small stockholders at an entertainment, including costumed cartoon characters, movie excerpts promoting coming attractions, and a chance at the microphone to tell the world who you are and what you think. Such promotion is even more effective if the meeting city shifts each year.

This year it was Philadelphia's turn to see the sights, including top executives in new suits and Ronald-Reagan shirt collars. Several thousand true believers in the American Dream did show up, many of them bringing little children, taking almost three hours to get through an airport-like electronic frisking by four harried security guards. The guards seemed particularly concerned to prevent live cell phones from entering the meeting.

Secondly, the meeting gave all the signs of a covert filibuster. It even had a professional: Senator George Mitchell, the former Democratic majority leader of the U.S. Senate, was on hand to advise. After all, a frivolously protracted meeting is collapsible if discussions get out of hand, because the audience has already become impatient. Comcast, with corporate headquarters only three blocks from this Convention Center, had an active offer to acquire Disney, instantly rejected by the Disney board. As soon as the offer was announced, the price of Disney stock jumped four dollars a share, enriching every shareholder in the room a collective $8 billion. Why not accept it? The new price now made the offer seem too low, by some perplexing reasoning. Allowing a succession of irrelevant speeches positions the chairman of the meeting to smother, in the interest of fairness to all, and gathering momentum for Comcast. In the event, it did actually delay this meeting's announcement of voting outcome, which was called for 8 AM, until past the close of the New York Stock Exchange in the late afternoon. Meanwhile, the message was encouraged that love of cartoons, wholesome television, and family vacations was more appealing to true stakeholders of Disney than vertical integration and short-term (read, short-sighted) profits.

|

| Michael Eisner |

It didn't go that way; hardly a word was said about Comcast. Instead, the true believers, led by the nephew of Walt Disney, made it clear that they were turned off by speeches filled with business school lingo, like enhancing the brand, protecting the franchise, and growing the business. They didn't understand all that, but they did understand that the American heartland was being asked to pay eight and nine-figure incomes, year after year, to people who obviously worshiped in the financial cultures of the East and West coasts. The most telling remark was that the company had good years and bad years, but Michael Eisner the CEO -- never seemed to have a bad year. Stockholders were urged to withhold their votes from him.

To some extent, any management engaged in a proxy battle has some justification for limiting the attendance at a stockholders meeting, because arbitragers will almost always try to support a hostile proposal. Stockholders who bought their shares a few days before the vote have interests which conflict with the long-term stockholders since a short term jump in stock price will probably evaporate if the proposal is defeated. Many of the people in the audience are only there to assess whether the proposal is likely to be successful, so as to buy more shares or sell what they have; some of the people at the microphone are potentially interested only in misleading these observers. The wise guys in the audience were agreed that Comcast had made a mistake announcing its offer after the date had passed when newly-purchased shares were eligible to vote.

In the end, over a thousand people stuck it out to hear the ballot results. After seven hours, someone moved for adjournment, the chairman heard a second, a scattering of eyes followed, and he never called for the nays. He was half-way to the door when a thousand howls were raised, demanding the results of the vote. Oops, sorry. An accountant was summoned to drone out interminable numbers, one by one. It seems that seven hundred million shares had withheld approval from the CEO, 43% of the votes cast. Mr. Eisner, to his credit, didn't show a flicker of emotion on his televised face, and duly announced that all directors had been re-elected, the auditors re-appointed, and the stockholder resolutions defeated. Maybe so, but at the board reorganization meeting which followed, Eisner was removed from the Chairmanship although retained as CEO. The more logical person to defend the Magic Kingdom against predator Comcast was Roy Disney, of course, but to appoint management's public enemy would have been a bit much. Almost all of the board had themselves experienced at least 200 million votes withheld.

|

| Ned Johnson |

The real governance crisis which this carnival dramatizes was not mentioned. With nearly two billion shares outstanding, at $26 a share this company is valued at $52 billion. There were people at the microphone who owned 200,000 shares, but even their economic power is negligible in a corporation so large. It is the managers of mutual funds and pension funds who now control big-corporation voting, and have the real power to decide on mergers and take-overs. Mutual funds and pension funds, like Ned Johnson at Fidelity who controls a trillion dollars of various stocks, are the ones with the votes. In the past, such managers have found it a bore to address five hundred or more proxy statements each spring. They find it hard enough to hire analysts who can pick a good company, let alone picking executives to make a bad company into a good one. As fund ownership has spread, however, there is uncomfortably little left to buy if a diversified fund does much selling. Diversification is almost a sure winner; picking executives is too much like picking racehorses.

So, in the end, the restless stockholders were guided by only one perception: Eisner controlled his own pay and took too much for himself. Too much diversification of stock ownership has led to the dispersion of control. And dispersed control has led to control by outcry. Those friends of capitalism who dread government regulation had better rapidly devised some alternatives.

Barnes Foundation -- Drawing a New Moral

|

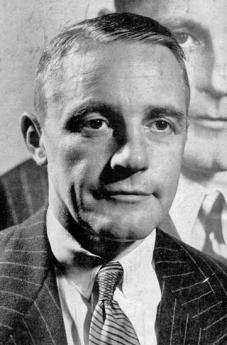

| Andrew Stewart |

Andrew Stewart, the Public Relations Director of the Barnes Foundation, and for thirteen years a member of its Board of Directors, recently addressed the Right Angle Club. He gave a new slant to the quarrelsome saga of Dr. Barnes' will, offering the point of view in favor of moving the paintings to the Parkway. It's useful to hear the legal and historical background because about all we hear are criticisms, balanced by joy at having the famous paintings where we can see them.

Essentially, the will declared a wish for the School and Museum to follow the original indenture. After the passage of time, the old board members died off, and the new board members found the Indenture to be out of date, like specifying the purchase of railroad bonds. Delivered in a charming Scottish brogue, the argument was fairly convincing. But it stimulated in me an entirely different moral from the eternal dispute between the right of a man to have respect paid to his expressed wishes for his own property, versus the self-defeating quality of the same restrictions with the passage of time.

|

| Barnes Foundation |

Barnes was born in Kensington, and had a hard life as the son of a Civil War veteran who lost an arm in the war, and had a dismal time making a living as a butcher. Barnes was his fighting-spirit son, who worked his way through medical school. It was Jefferson Medical College, where I was on the faculty for decades. While it is true his patent medicine gave a permanently sickening color to the children who were treated for sinusitis, it is also true that in the form of eyedrops it prevented the transmission of syphilis to millions of newborn children. In that view, it was a real scientific contribution, although the medical profession continues to take a dim view of doctors advertising their wares. Although he was himself a failed artist, Barnes was a highly successful collector of (then) modern art and started a school with John Dewey to teach art appreciation to poor people. One by one, the local universities snubbed his wishes for an art appreciation school, and the local Philadelphia museums were pretty sniffy about his favorite artists.

In fairness to them, Barnes was probably pretty pushy in his demands. Unfavorable local reception to an exhibition which had received rave applause in Paris, convinced Barnes he was right and they were wrong. After this, Barnes developed a lasting hatred of Philadelphia and all its stuffy ways; he definitely didn't want his own impressionist art to be in Philadelphia, which would never appreciate it. While Philadelphia finally woke up to the value of Impressionist painting, Barnes never relented while he was alive. I hope I give a fair portrayal of the argument except for the politics and the legalities, that I know very little about.

But hearing the arguments, I see an entirely different moral to the saga. Ever since the inflation of the 1930s, fine art has appreciated in value, faster than the endowments to maintain the art. (That's probably a useful tip to investors, too.) It's fairly standard for a wealthy person to donate his art collection, plus a sum of money to endow the maintenance of the art. Most of the time, the size of the endowment is carefully calculated to grow at least as fast as the value of the paintings, because you have to ensure them, and pay for increased security, and increasing attendance. With the new trend toward inflation of at least 2% a year, the old premises don't work anymore, and the endowment eventually runs out. At that point, it runs into restrictions which -- to be perfectly blunt -- were created to prevent the trustees from pilfering the museum. A museum may not sell its art to pay for administrative expenses.

Consequently, The Barnes ran into a situation where it had billions of dollars worth of paintings in the basement, which it could not sell, and could not even hang in the museum because of Barnes' specifications for what went on the walls. This situation isn't going to change, because a dollar in 1913, when the Federal Reserve was created, is now scarcely worth more than a penny. And the present Fed is committed to 2% inflation, forever.

So, how about this: let the lawyers who write wills, and the Orphan's Court which administers them, insist that the art collection be divided into two parts. One would be the permanent collection, just as at present, and the other would be eligible for sale in the judgment of the Orphan's Court.

Billy Penn's Hat

|

| Billy Penn's hat |

Philadelphia City Hall was intended to be the tallest building in the world, so there was no reason to suppose anything in Philadelphia would be taller. Gradually, taller buildings in other cities were built, but there grew up a gentleman's agreement that no skyscraper would be built in Philadelphia that was taller than William Penn's hat atop his statue on the tower of City Hall. Planning in the city was organized around this premise, which affects subways and other transportation issues in the city center. Because of assassination fears, a similar tradition in Washington DC was enacted into law, and it must be admitted that the flat skyline of that city looks a little dumb and boring. But Philadelphia neglected to pass a law, and so at the end of the Twentieth Century first one and then half a dozen skyscrapers were built that were twice the height of City Hall, immediately destroying the organizing visual center of the city. Pity.

But there are more serious issues involved. Aesthetics aside, who cares if someone bankrupts himself building an inappropriately tall building, with excessive elevator costs, problems with reinforced foundations, shortage of parking space, and the like? And the answer to that is the new tall building will bankrupt the older office buildings, not itself. Using offers of low, low rents to fill the new building, tenants will be drained from other spaces, and other areas of the city will deteriorate unless there happens to be a general shortage of office space in the region. Carried to an extreme, all of the center city business might be envisioned to reside in one thousand-story building, and the rest of the region would be a desert.

The obvious response would be that no landlord wants to have competition, and new construction is the way a city renews itself, creatively destroying the old to make room for the new. You must not allow the vested landlords to capture the political process with agitation if not bribes. Push things too far in that direction, and you will find that political corruption has destroyed the fabric of the town more effectively than a couple of skyscrapers ever could. Market East has been devastated, it is true. But that's the price of conducting the commerce of the region on the basis of market economics instead of through bureaucracy which masks corrupt politics with high-flown language. Paris is beautiful, but France has 12% unemployment which is closer to 16% if you remember the 30-hour week, the nine-week vacations, and retirement age in the fifties.

And yet, there is certainly a point to be made here. The height limit on new construction must bear some relationship to the regional need for new office space, and not merely rely on beggar-my-neighbor. We're currently hearing about two new projected skyscrapers, one beside 30th Street Station, and the other at 17th and Market/Chestnut. The decision to go or no-go will rest with whether the developers can find "lead" tenants. The corporate officers of these large enterprises are the ones who must be expected to give careful consideration to the best interest of the community because right now they are the ones who control matters. If they neglect their responsibilities, the pressure to pass more zoning laws will prove hard to resist.

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing

|

| Statue of Diana |

The brownstone house at 1710 Spruce Street is seemingly not remarkable, it's just an Edwardian house now converted to lawyers' offices on the first floor. But it's nevertheless a landmark, curiously linked to that 13-foot statue of Diana which dominates the top of the main interior staircase of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Many Philadelphia gossips believe the model for the statue was Evelyn Nesbit, who lived in the brownstone on Spruce Street. But she was born in 1884, whereas Augustus Saint-Gaudens created the statue for the 1892 Columbian Exhibition. Since Evelyn was only eight years old at that time, however, it must have been some other woman who took off her clothes to pose for the sculpture; for us, it doesn't matter who she was. The statue was moved to the top of Madison Square Garden when that structure was really still located on New York's Madison Square, but when the Garden was demolished in 1925 the Diana statue came to Philadelphia. Madison Square Garden itself has moved twice in the meantime and is mostly associated in the public mind with prize fights and political conventions. However, when the first Garden was built, it had theaters and roof-top restaurants, and its spectacular nature instantly made the architect, Stanford White, the most famous architect in New York, eventually maybe the most famous one in the world at the time.

|

| Thaw |

Meanwhile, two residents of Pittsburgh independently came to New York where the action is, the iron and coal millionaire Harry K. Thaw, and an impoverished teenager named Evelyn Nesbit. Evelyn was accompanied by her mother who, recognizing the girl's extraordinary beauty, set about to steer her to fame and fortune. At the age of thirteen she was posing for artists, and in time became the favorite model for Charles Dana Gibson. Gibson created the "Gibson Girl", an idealized role model for millions of women who dressed the way she did, wore their hair the way she did, and behaved in the proper Edwardian style they imagined she did, too. It was in Gibson's studio that she encountered Stanford White. Evelyn had another life, however, as a "Florodora Girl", and one of her many stage-door Johnnies was Harry K. Thaw, the millionaire. That was no saint, having a reputation for using a dog whip on his numerous lady friends, but it is uncertain whether he was completely aware that

|

| Evelyn Nesbit |

Evelyn was one of the principle entertainers in half a dozen hide-aways that Stanford White is said to have established for naughty parties to amuse New York's fast set. That was certainly aware that Stanford White had been Evelyn's boyfriend before Thaw married her, and the two men cordially hated each other. One evening, some provocation made Thaw walk over to White's table in the rooftop restaurant of Madison Square Garden, and shoot him dead -- in front of hundreds of people. It's a curious sidelight that Stanford White was carrying a train reservation to Philadelphia, to discuss plans for the domed structure of the Girard Bank building. The notoriety of the murder trial was the sensation of the decade, with the prosecutor remarking that White deserved what he got, and Thaw's mother offering Evelyn a million dollars if she would give testimony supporting a plea of insanity. Everyone seems agreed that the money was never paid, although the jury was sure as impressed as the newspaper reporters with Evelyn's refusal on the witness stand to testify against her husband, quite evidently a sign of loyalty. Anyway, the jury let him off, and a famous cartoon depicted Stanford White in the pose of the statue of Diana.

|

| Joan Collins as Evelyn Nesbit "The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing" |

Evelyn sort of dropped out of sight after the trial and the subsequent divorce, until TV interviews were conducted for the movie about the episode, \"The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing". By 1957, Evelyn was decidedly less of a beauty. Meanwhile, Harry K. Thaw had continued to live in the brownstone house in Philadelphia, where once he got sick and called a friend of mine to be his doctor, and eventually another famous professor to be a consultant. When the butler answered the door, the consultant told the butler to tell his employer that he must insist on cash in advance, an action that thoroughly embarrassed my friend in view of the famous wealth of the client. But the consultant had rightly assessed the situation since later Thaw's lawyer called up and told the family doctor he was sorry but his client was not going to pay his bill since the medicine was started by some botanical book to be a poison in excess quantity. In consternation, my friend called up the professor and asked what to do. "Chalk it up to experience," was the answer. "But what have I learned?" The consultant paused, and said, "Maybe you have learned to extend credit only to decent people."

Immigration

|

| Gold |

We're alluding indirectly to immigration as a general topic in this article because sooner or later every discussion of every aspect of immigration adds a claim of "fairness" to the balance. In this case, plain talk about fleecing peasants first requires the definition of an unfamiliar term. Seigniorage, also spelled seignorage, or seigneurage, originally only denoted a fee which governments charged for milling coins out of precious metal. Developing nations often didn't have the necessary technology, so they paid some other country to do it for them. That was fair enough, but soon "trimmers" would shave the side or surface of coins and gather up the dust for sale. That practice led to clever serration of the formerly flat edges, much simpler than weighing coins to detect cheats.

In time, improved printing techniques allowed governments to keep precious metal in vaults and issue paper currency, some of which inevitably got burned, shredded or lost. Since the issuing government could then keep the whole value of lost currency minus printing costs for itself, the term seigniorage evolved to include this more lucrative method for governments to cheat citizens, abusing their monopoly on the currency issue. There might seem to be some temptation for governments to print money on fragile paper, except it is overbalanced by the need to make it hard to counterfeit. Happily, this sort of seigniorage always seemed less offensive because everybody agrees that if you have money in your pocket, shame on you if you lose it. As transactions become more sophisticated, however, some innovative modern arrangements which loosely fit the definition of seigniorage become a new source of moral dismay. One facet of currency razzle dazzle concerns immigration, which is itself always a contentious matter.

|

| Spanish |

Right now, it is authoritatively estimated that the Social Security program has collected half a trillion dollars in Social Security and Medicare taxes, whose rightful owner is impossible to determine. Some of the beneficiaries may have died without claiming the money, so some of this topic might be classified as escheat, or abandoned by the owner. But very likely the bulk of this money, under modern circumstances, was withheld from illegal immigrants by their employers, either without their knowledge or using counterfeit social security numbers; and the fugitive status of the owners made them reluctant to claim it. Half a trillion is five hundred billion dollars.

This sort of discovery leads to some troublesome thoughts. If the immigrants are legal, or if now illegal may receive amnesty, they will be fully eligible for social security benefits. You might say they earned such benefits, but our tormented public pension system is in fact almost entirely funded by one generation funding its parents' generation. That borrowing between generations means paying for it later, so of course, it enjoys the politician spin-term of "pay as you go". An American of multi-generational descent has paid for his parents while he works and expects to have his own pension paid for by his children. An immigrant, never mind his citizenship, is paying the same taxes, but has no parents as beneficiaries. When the newcomer retires he may be a burden to his children like the rest of us, but his current payments go into the black hole of government deficits without paying for any parents. Here we have seigniorage on a much grander scale. The money presently diverted from the usual channels by this ingenious arrangement is calculated to be two trillion dollars, or four times as much as the paper money seigniorage, and many many times as much as the shaved-coins scam. Just for comparison, consider that America is estimated to have 900 billionaires. Their aggregate net worth is probably only slightly greater than the amount our government garners from illegal immigrants.

The matter really does seem to be important enough for us to learn how to spell seigniorage, and even reconsider whether to apply the term to its most popular current manifestation.

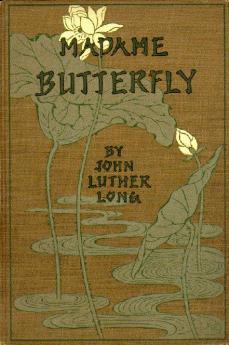

Madame Butterfly (2)

|

| John Luther Long |

There are two ways of looking at the love affair of Pinkerton, the dashing Philadelphia naval officer, and Madame Butterfly, the beautiful Japanese geisha. John Luther Long wrote about it one way, while Puccini somehow portrays it differently, even though Long collaborated on the Libretto of the opera. Puccini, of course, was himself a famous libertine, tending to follow the typical belief of such men that women somehow enjoy being victimized. Long in real life was a Philadelphia lawyer, trained to keep a straight face when people relate what messes they have got into. If you know the story, you can see Long in the person of Sharpless, the consul. Sharpless is definitely meant to be a Philadelphia name.

|

| Madame Butterfly |

Long was one of the early members of the Franklin Inn, and it is related he wrote much of his successful play at the tables of the club on Camac Street. David Belasco was the "play doctor" who knew how to make a good story fill theater seats. Even after Belasco's polishing, the play came through as a portrayal of the well-born gentleman who had been trained to regard foreign girls as just what you do when you are away from home. His real girlfriend, the beautiful Philadelphia aristocratic woman in a spotless white dress, was the sort you expected to marry. In just a few sentences of Long's play, this woman comes through as just about as distastefully aloof to foreign women as it is possible to be while remaining rigidly polite about it. Butterfly sees this at a glance, knows it for what it is, and knows it is her death. Her duty immediately is "To die honorably, when one can no longer live with honor".

It is Puccini's genius to take this story of how two nasty Americans destroy an honorable Japanese girl and using that same story with the same words, make it into a romantic woman being destroyed by a hopeless, helpless love affair. The power of the music overwhelms the story and sweeps you along to the ending. Even if you feel like Long/Sharpless, dismayed and disheartened by watching some close acquaintances doing things you know they shouldn't.

When Puccini's opera comes to Philadelphia every year or so, the Franklin Inn has a party for the cast, one of the great events of the Philadelphia intellectual scene. Somehow, the full intent of Luther Long's work never seems to come out.

RICH Wagner, the author of Philadelphia Beer, recently visited the Right Angle Club. It's hard to imagine that Philadelphia was once the American center of beer production, with hundreds of breweries and their associated bottlers, beer gardens, brewing equipment, and horse-drawn beer delivery systems, dominating the city scene. Equally hard to imagine that the last Philadelphia brewery closed in 1987, and the biggest American brewer, Budweiser, was sold to the Belgians in the past year. What's this all about?

|

| Francis Perot |

In the early wilderness days, water supplies were tainted and unsafe, so most prosperous Quakers had their own little brewery just to avoid typhoid fever. The first American brewery was started by Anthony Morris (the second Philadelphia Mayor) in 1687, in a little brewery on Dock Creek, which became the early Brewerytown of the city, with several dozen brewpubs for sailors and the like. In 1797 there were over a hundred breweries in Philadelphia, and in 1840 there were over three hundred of them. Perot's brewery was prominent for a long time since an early Perot married a daughter of Anthony Morris. Since Philadelphia developed the first and famous city water supply in 1800, beer drinking lost its position as a safe beverage in an unsafe city, and gradually water-drinking became the dominant beverage for the strict and upright. At one time in the early Eighteenth century, gin was cheaper than beer, so even the intemperate multitudes deserted beer for a while, although the effect of the higher alcohol content of gin was apparently fairly dramatic.

|

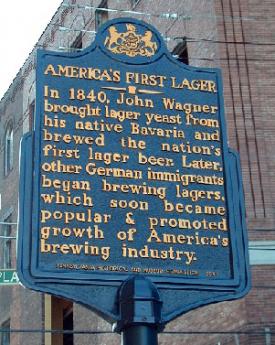

| John Wagner Marker |

In 1840 John Wagner imported the yeast for lager beer from Bavaria, at considerable personal risk if he had been caught at it. Prior to 1840, Philadelphia beer was either stout or Porter, a very dark and bitter dose, or else ale, which had the advantage of storing fairly well and thus was popular for sailing vessels and among sailors. The yeast for ale floats to the top and ferments, whereas lager yeast sinks to the bottom of the barrel and requires some refrigeration to slow it down. In all forms of beer, the suds are created by later adding some unfermented beer to the barrel for the purpose of generating carbon dioxide. That's what is going on when you see the bartender in a British pub pulling on a lever to pump it up from the basement. Lager tastes much less beery than other beer and is by far the dominant form of beer in consumption -- a considerable improvement, in the view of most people. But it has to be cooled, and Philadelphia had a system. Brewerytown moved to Kensington, dominating the local scene. It was produced in barrels which were trucked to the east bank of the Schuylkill where ice formed on the surface of the river, stilled by impoundment above the Fairmount Dam. Caves were dug in the banks of the Schuylkill where the barrels full of fermenting beer were hauled to be cooled by the ice for the rest of the process. From there, it was trucked again to bottlers in a general ratio of one brewer for thirty bottlers. More directly, it was trucked to the beer gardens of Spring Garden to Girard Avenue, which gave that area a different sort of reputation as a brewery town. By this time, most of the breweries had moved to the region between 30th and 33rd Streets, near Girard, and most of them still survive, made into condominiums by rehabilitation money. One by one, many sections of downtown Philadelphia acquired a beer environment. A dramatic moment in this process was the advent of the 1876 exposition, which caused many of the Schuylkill fermenting vaults to be acquired by eminent domain. A second momentous change was introduced by the invention of refrigeration, apparently invented in Germany near Berlin, but imported and refined by York and Carrier. Philadelphia was particularly suitable for the importation of coal to fuel the heating of the brew, and the chilling of the fermentation. All of this required large numbers of brewers, bottlers, makers of bottles and inventors of brewing equipment. It took many horses to haul all this material around town, and many teamsters to drive the horses. This was a beer town, until Prohibition.

During the long period of beer ascendency, the advantages of big breweries over small ones were gradually making this a major industry, rather than a local craft. Prohibition completed the destruction of the small craft brewers and brew-pubs. Only 17 of the major brewers survived Prohibition, and then even the big ones went out of business, ending with Schmidt's in 1987, almost exactly three hundred years after the first little one started by that famously convivial Anthony Morris on Dock Street. Evidently, the same competitive disadvantages continue as even Budweiser moves to Brussels, where you would ordinarily expect the wine to be the popular drink. Changing tastes have been cited as the reason for this shift, but differential taxes seem more probable as an explanation. In most industries, you are apt to find that most of the competition takes place in Washington and Harrisburg, rather than the saloons of Main Street or the salons of Madison Avenue. But perhaps not. We hear that little Belgium is about to have a civil war because the Flemish can't get along with the Walloons. And somebody in Portland, Oregon got the idea that beer was trendy, and started up the growing phenomenon of craft brewers, usually flourishing in brewpubs. We are apparently going back where we started in 1687.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in the Cradle of Liberty: Rich A. Wagner: ISBN: 978-1609494544 | Amazon |

Philadelphia's Republican Machine

From time to time, someone denounces big-city political machines, making the mistake of describing them as invariably Democrat. Debaters duly object, pointing to Philadelphia's Republican city machine lasting seventy-five years. It was, indeed, a very tough and corrupt organization. Whether it was Republican, is more debatable. The question might be re-phrased: How is it, with Democrats running every other big-city political machine, Philadelphia alone produced a Republican version? The explanation is buried in complex national politics just before the Civil War, when the last and final Whig convention was held in Philadelphia, following which the successors, the Republicans and also the Know-Nothing (American) parties, held their very first conventions here four years later.

|

| James Buchanan |

To stir the Philadelphia pot still further, the person who actually won the 1856 Presidential election was James Buchanan, a Democrat from Lancaster County. Just about everything political was happening right here, all at once. Lots of deals were made. The Pennsylvania Republican delegation emerged as Abraham Lincoln's king-maker, and Lincoln as President rewarded Pennsylvania for its keen insight. Appointing cabinet members from Pennsylvania, the new administration naturally steered war contracts to our local industries. Philadelphia politics immediately became Republican in a big way, and after the war, the Republicans were then in charge of the national government for fifty years. Philadelphia had created a political machine, and it made no sense patronage-wise for many decades, for it to profess allegiance to any other party than the one it started with.

There thus exists a simple and coherent explanation for Philadelphia's exceptional behavior. A more difficult question to answer beyond dispute is: Why do big-city political machines almost invariably develop a Democrat affiliation? We're going to take a pass on that one, falling back on the observation that municipal politics usually have very little to do with national politics, no matter what Tip O'Neill may have said. Indeed, local politicians mostly wish national politicians would go back to Washington and leave them alone. National politicians certainly reciprocate that feeling, especially if they have a safe district.

But Party unity is periodically stimulated (some would say simulated) when the national figures must come back home from Washington seeking voter approval, searching out support in the clubhouses, fire stations and taprooms that are firmly in control of local warlords. Those warlords care little about foreign affairs, interest rates at the Federal Reserve, or globalization, becoming uneasy when the national politicians to whom they owe nominal fealty drag them into messy subjects like abortion and civil rights. In the clubhouses, there is a tendency to measure national leaders by patronage and pork barrel. In return, the national representative wants to be re-elected. He wants voter turnout, campaign funds, and gerrymandered districts. It's mostly the same in both parties, and in all regions.

Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia

|

| Professor Digby Baltzell |

Digby Baltzell had something of the defiant rebel in him. He surely didn't imagine his employer, the University of Pennsylvania, was pleased to have him a document that Harvard is a better college than Penn. Nor were fellow members of the Philadelphia Club pleased to confront scholarship that his city's gentry was too devoted to money-making to accept the ardors of public leadership. Nor would his relatives in the Society of Friends enjoy accusations their religion impaired the pursuit of excellence in all fields of the city's endeavor. Later articles will here take up some unfair assaults, and defend Quaker simplicity and Peace Testimony. Some blame must, of course, be shared, some mitigating circumstances acknowledged. And let it be said in Baltzell's support that it truly is remarkable how many cultural features do get passed down for ten or more generations. Or even longer; look at the persistence of ancient Chinese, Indian, Esquimo, Viking, Roman, Christian and other cultural heritage. The Quakers got to Pennsylvania early, they are now vastly outnumbered. Many Quaker ideas continue to influence present inhabitants, some ideas probably hold us back. Substitute "Puritans of Boston" for "Quakers" in the foregoing sentence, and conclude by saying "some of those ideas probably give Bostonians an edge". Those two rather unexceptional declarations summarize a controversial book, although they do not completely capture its overall censorious flavoring.

To a certain extent, Digby is his own worst enemy. While alive, he was one of the world's most charming raconteurs, a walking encyclopedia of local lore. Like a good docent in a museum, he could walk into a room hung with portraits, and charm any audience for an hour; presumably, his sociology lectures at Penn held the same magnetism for his classes. In a book for popular readers, however, it is overdone to go on about the same point for six hundred pages. He needed a better editor, or perhaps he needed to permit a better editor to make him restrain his tendency to multiply illustrations beyond the point where the reader loses the thread of the argument. Not all readers will agree with his argument; they can only be legitimately defeated by focused argument. That's perhaps unrequired of college professors holding the power of grade-point averages over nineteen-year-olds, but it is expected of conversation with other adults. If an editor wants to sell books to a general bookstore audience, he should induce authors to overcome the take-it-or-leave-it habit.

As a general reaction to this book, Baltzell seems to think Quakers do not want to be rich and that consequently, latecomers into the region tend to share this feeling. My own view is that Quakers see they can have almost all of the value of being moderately rich -- by disdaining the trivial luxuries of the middle classes. They do not exactly renounce fame and power but are unwilling to gamble much or sacrifice much, in order to enjoy the comparatively small exhilaration of being very rich. They are now no longer surrounded by junior versions of themselves, but by bank-robbing Willie Suttons who readily attack Quakers for being where the money is, and appear to be pushovers at that. When Quakers then promptly demonstrate they are not pushovers at all, they are treated like outsiders in their own town. In many ways and at most times, the populist crowd gives up trying to understand Quakers and decides they must somehow always behave in ways that others would not. It's hard to achieve much deference in such an environment.

Many of Baltzell's important insights grew out of his position as a Philadelphia and academic insider; he personally knew many of the people he described. However, such an infiltrator runs the constant risk of being viewed as a tattle-tale, so a cover is required. Batzell's technique involved frequent use of quotations from others, not so much to prove a point as to rephrase it. This is another feature of the book which might have benefited from a hard-nosed editor. However this is how he wanted it, and in a post-publication revision, here is a condensation of how he summarizes his argument:

When studied with any degree of thoroughness, the economic problem will be found to run into the political problem, the political problem, in turn, run into the philosophical problem, and the philosophical problem itself to be almost indissolubly bound up at last with the religious problem.

--Irving Babbitt

In the South, ....left-wing Quakers came to the fore in the pine barrens of North Carolina-- to this day, North Carolinians speak of their state as "a valley of humilities between two mountains of conceit."

--E. Digby Baltzell

The world is only beginning to see that the wealth of a nation consists more than anything else in the number of superior men it harbors.

-- William James

I believe that ambitious men in democracies are less engrossed than any other with the interests and judgments of posterity; the present moment alone engages and absorbs them...and they are much more for success than for fame. What appears to me most to be dreaded, that in the midst of the small, incessant demands of private life, ambition should lose its vigor and its greatness.

-- Alexis de Tocqueville

Our rulers today consist of a random collection of successful men and their wives. ....They have been educated to achieve success, but few of them have been educated to exercise power. Nor do they count with any confidence upon retaining their power, nor of handing it on to their sons. They live therefore from day to day, they govern by ear. Their impromptu statements of policy may be obeyed, but nobody seriously regards them as having authority.

--Walter Lippmann

Equalitarians holding...extreme views have tended to believe that men of great leadership capacities, great energies or greatly superior aptitudes are more trouble than they are worth.

--John W. Gardiner

In the Jacksonian era in this country, equalitarianism reached such heights that trained personnel in the public service were considered unnecessary...Thus, in the West, even licensing of physicians was lax, because not to be lax was apt to be thought undemocratic.

--Merle Curti

In the late eighteenth century we produced out of a small population a truly extraordinary group of leaders-- Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, Monroe, and others. Why is it so difficult today, out of a vastly greater population, to produce men of that character?

--John W. Gardiner