2 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Art in Philadelphia

The history of art, particularly painting and sculpture, has been a long and distinguished one. If you add in the art schools, the Philadelphia national influence on artists has been a dominant one.

Mary Cassatt

|

|

The most famous Philadelphia Cassat shows a mother driving an open carriage with small daughter beside her, and her brother on the back seat. |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) is variously proclaimed as the greatest woman artist ever, and America's greatest impressionist painter of either sex. She is thus, from a Philadelphia perspective, the greatest Philadelphia woman artist. Mary was, in truth, born in Pittsburgh spent most of her artistic career in Paris, and relatively few of her numerous pictures are to be found in Philadelphia. But she spent four years training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, her family moved to Philadelphia, and what is most important of all, her brother Alexander was president of the Pennsylvania Railroad at a time when such a position was nearly the same as being King.

|

|

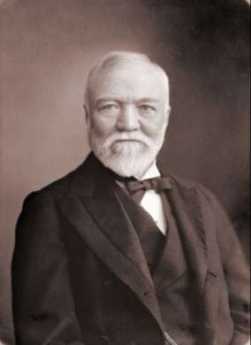

Alexander Cassatt President of the Pennsylvania Railroad |

Almost all of her many paintings used members of her family as models, and almost invariably the paintings portray women or young girls. If there is a male in the picture (and there are a few), you have to recheck the label to be sure it is a Cassatt. This bias raises questions about her private life, which she would certainly have regarded as no one's business. She was the long-term competitor of a slightly less famous Philadelphian Paris artistic exile, Cecili a Beaux, and she was very active in the suffragette movement. On the other hand, she had a forty-year relationship with Degas, with whom she was professionally very close, as well as personally.

Mary Cassatt was a classmate at the Pennsylvania Academy of Thomas Eakins, but they did not get along. The master anatomist and the greatest woman impressionist were certainly hampered by professional disagreement; apparently they both took it personally.

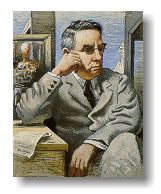

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

A private investor has the general goal of accumulating enough wealth so, come what may, there will be a little left when he dies. If he has dependents or heirs, he needs somewhat more. Either way, he is not planning for perpetuity or thinking in astronomical time periods. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) had to switch his investment goals, in the 1920s, from investing for a comfortable retirement to investing for a perpetual art foundation. Perpetual.

|

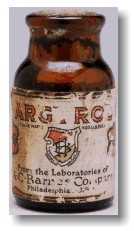

| A bottle of Argyrol |

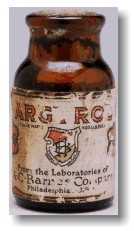

Having graduated from medical school (University of Pennsylvania) in 1902, and then writing a doctoral thesis in chemistry and pharmacology at the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, Barnes invented a patent medicine that quickly made him rich. Argyrol was a mildly effective silver-containing antiseptic with the unfortunate tendency to turn its users permanently slate-gray. The advent of antibiotics has since made Argyrol almost sound like quackery, but it was effective enough at the time to require factories in America, Europe, and Australia, and Barnes became immensely rich with it. The American Medical Association strongly disapproves of physicians who patent remedies, so Barnes was never held in high regard by his colleagues; but it could well be argued that he had as much training as a chemist as a physician, and spent his entire professional life as a chemist, manufacturer, and investor.

|

| The Barnes Gallery |

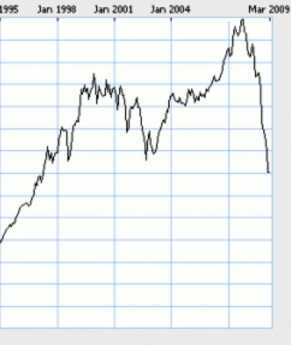

Barnes was eccentric, all right, but on Wall Street, the saying goes, "What everyone knows, isn't worth knowing." Guided by that principle, in 1929 he sold his company at the very peak of market euphoria, getting out of common stocks at the top of the market. It is small wonder that he soon instructed his Foundation to invest its endowment entirely in bonds. During the 1930s, commodities were extremely cheap because no one had any money. Barnes, of course, had a potful of money and bought hundreds, even thousands, of artworks very cheaply. He also bought 137 acres of Chester County, PA, real estate, and a 12-acre arboretum in Merion Township on the Main Line. Although he is famous for acquiring hundreds of French Impressionist paintings with the advice of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, he also bought great quantities of Greek and Roman classical art, African art, and the art of the Pennsylvania German community. He picked up a notable collection of metallic art objects. Most of these "losers" are down in the basement because he had so many Renoirs, Matisse, and Picasso (some of them may be worth $200 million apiece) that the upstairs galleries were pretty well stuffed with them. Viewed from the perspective of an investor with a goal of perpetuity, of course, the things in the basement just happen to be temporarily out of fashion, just like those bonds in the portfolio.

|

| A view inside the Barnes gallery |

Since the Foundation is currently strapped for ready cash, Judge Stanley Ott of the Montgomery County Orphans Court is now being urged to allow the Foundation to break Barnes' will in some way or other. Move the museum to downtown Philadelphia where it can attract more paying visitors. Sell some of that land. Sell some of those paintings in the cellar. Fire some of those employees. But all of these suggestions are short-term solutions, which may injure the long term. Everybody has an idea of what Barnes the rich eccentric would have done if he were alive to do it, but I suspect he would have rejected the whole lot. Barnes the shrewd investor would have taken the most expensive painting off the wall, and sold it to the highest bidder. Buy low, sell high, and the niceties of non-profit professionals are damned. Barnes wasn't in love with one single painting, or one particular school of painterly interpretation, he was in love with Art.

Investment theory has improved in the past fifty years; there have even been some Nobel prizes awarded for new insights. But it still isn't possible to put an investment portfolio on autopilot for perpetuity. Every museum, university, and the foundation has the same problem, with the result that the landscape is littered with the bones of perpetual organizations destroyed by following a fixed formula. With the singular success that Barnes displayed, it isn't surprising that he went a little too far with instructing his successor trustees in what to invest in. Never sell the paintings or the real estate, avoid the common stock, were ideas that worked brilliantly, and may even work most of the time. But sooner or later, the institution will be endangered by following them too literally. Somebody has to have some flexibility. But there is something else that is inevitable, too. Sooner or later, whether it takes fifty years or five hundred years, sooner or later someone will be given the responsibility and the necessary flexibility -- but will try to run off with the boodle, for himself. The balance between necessary prudence and necessary flexibility is impossible to maintain forever, and the Judge will surely have a hard time deciding what Barnes would have decided.

Cecilia Beaux, Portraitist of the Grand Manner

|

| Cecilia Beaux |

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) was certainly the most famous woman portraitist of her time. She had the misfortune of being a contemporary of Mary Cassatt, who enjoyed the reputation of the finest woman Impressionist at a time when the Art world disdained traditional painting techniques in an Impressionist stampede. So, although these two temperamental artists might never have been chums, much of their famous rivalry was probably invented for them by art world politicians.

In time, the assessment will emerge that these two well-born Philadelphia ladies were each the world's female leaders of two competing schools of art. Comparisons of the two will also have to be filtered through the fact that Cassatt was a rebel who spent most of her life in Paris, while Beaux was a prominent faculty member of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for twenty years. Strikingly beautiful herself, she was gifted, elegant and fiercely ambitious. Meow.

|

Once Beaux had established a reputation as a portrait painter, she shrewdly began to select her subjects. She wanted famous men (Henry James, for example) and beautiful women subjects. She made the mistake of turning down her niece, Catherine Drinker Bowen, because she didn't have the right kind of cheekbones. She learned, of course, that it's unwise to tell a famous author she is ugly.

|

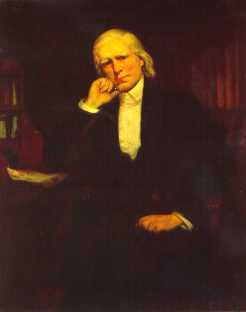

| Robert Louis Stevenson |

Cecilia Beaux's main competitor in the portrait game was John Singer Sargent, who was if anything a better painter but a stammering social dud. Sargent remained a life long bachelor, Beaux a spinster. Her mother had died in childbirth, and it seems likely that terror of pregnancy was an important part of her personality, during the pre-antibiotic era when such fear was fairly justified. As a young woman, she turned down proposals by the dozen, and in maturity, she had a succession of apparently platonic but intense relationships with handsome men twenty years her junior. During the late Victorian era, this sort of thing was not rare, although medical advances have apparently largely eliminated it. To return to her competition with Sargent, the personality differences probably account for his haunting portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, while Beaux is notable for arresting portraits of rich, famous and beautiful women, and an equal number of well-dressed, handsome men.

Priceless Art as Mass Entertainment

The Philadelphia Museum of Art recently had a special exhibition of paintings by Edouard Manet, with a heavy dose of Claude Monet plus a few others. A moment's reflection demonstrates the enormous undertaking it must be to assemble a hundred valuable paintings from 60 different museums and owners, arrange for permissions, negotiate insurance and shipping costs, debate the best display, lighting and arrangement, instruct the guides, print the brochures, hype the announcement hype, and probably a thousand other details of making this all come out right. Although a lot cheaper to assemble this show and move it around to various cities, than it would be to have thousands of Americans travel to Europe to see the paintings there, nevertheless it looks expensive. Half a dozen major foundations donated money for this effort, and the ticket price is not insignificant. When you are all done, however, you have seen a display that no one could possibly see privately, all in one afternoon, with an elegant lunch on the premises in air-conditioned splendor, accompanied by a small orchestral group in the background. The show is resident for three months, less two weeks for setup and travel, so four cities can collaborate on four traveling exhibits each year. Somewhere, there must be a very large staff devoting full time to keeping these exhibits in constant movement; probably several cycles are going at once. This is big business, and filling that big museum every day for three months implies that many of the visitors are from outside Philadelphia. After you go, at least you can tell Manet from Monet, you've had a taste of the huge Museum that makes you want to come back some day, and you have seen Philadelphia's best view, right where Rocky ran up the steps.

Our guide was well trained and entertaining, and knew all about horizons, prompting some deep, deep thought about horizons. The Dutch school of painters usually put the horizon down near the bottom of the painting, showing off the billowing grey clouds so characteristic of the European coast near the North Sea. By contrast, the French impressionists went down to the sunny Mediterranean coast, where the bright sunlight forces you to look down at the ground. So the horizon of painting, the line where the sky meets the ground, is low in northern paintings, but high in scenes of the Riviera, representing in both cases the typical viewer?s image of the scene. No doubt, some painters deliberately reversed the normal location of the horizon, in order to create the unconscious effect on the viewer that something was somehow wrong.

This little lesson has practical utility for those of us who take amateur snapshots. The rule for photographers is to throw the horizon into either the top third or the bottom third of the viewfinder. Avoid putting the dumb horizon right in the center of the photo. Since most cameras nowadays have an automatic exposure meter, if you get it wrong the meter will concentrate on the sky, underexpose the subject below the sky, and give you a puzzling black silhouette instead of a picture of your girlfriend.

Returning to the reality of the Art Museum, it sits on top of a little mountain --Fairer Mount-- that William Penn once considered as a place to put his home. It was later the site of a reservoir, with the famous pumping station and water works down the hill on the edge of the Schuylkill. Now, this Parthenon is an easy place to reach and to park, while the world's art is placed before you. The Russian Tsar in his Hermitage, and the Archduke in his Viennese palace never had it as easy as this.

Brandywine Museum

|

| Wyeth Ann's House |

Artistic talent must be inherited; some of us don't have any at all, while other families seem to have unusual talent in every member. Around Philadelphia, one notable example is the Peale family, and another is the Wyeth clan. Three generations of Wyeth's show their work as a group in a former Brandywine Creek grist mill which has been elaborately restored and enlarged for the purpose. Using large glass windows, part of the display is the Brandywine Creek itself, with the high banks that once made it seem like a perfect defense line for George Washington in the biggest battle of the Revolutionary War. Outside the museum entrance are several of those inevitable Delaware tip-offs, large millstones that may in this case have ground grist, but often were used to grind gunpowder.

|

| Andrew Wyeth |

Andrew Wyeth spent much of his early career doing watercolors and then turned to tempera as re-popularized by N.C. Wyeth, his father. That's a fairly drastic change, since a watercolor must be completed in one sitting before it dries. Oil base paint dries slowly and allows the painter to work on a piece for a number of days. Tempera, using the protein in milk and eggs to hold the pigment, dries hard and fairly quickly. But another layer of tempera can be painted on top of the hardened base layers, making a glowing effect possible, a peculiar luminosity if the artist chooses to bring it out. Andrew Wyeth migrated to what he called dry-brush, where the paint on the brush is mostly squeezed out, so extremely detailed fine lines can be painted. Thus, he spent his early years with fast blurred watercolors, and the rest of his life with meticulous slow painting, where detail is everything. He chose to use this technique to produce a haunting silent scene, even if it contained people. His son, Jamie, tends to emphasize dancers so you can see the typical family rebellions alternating between generations, at the same time that the Wyeth's (and Howard Pyle, the artistic forefather) preserve strong family unity. From what the neighbors say, there were plenty of family clashes, but that's artists for you.

Modernism and Postmodernism

|

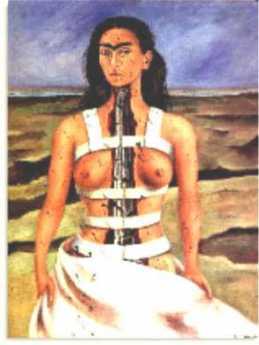

| Modernism |

Artists, musicians, authors and other participants in the cultural world are constantly seeking to innovate. Their eras, movements and other broad trends are mostly defined in retrospect. Quite unlike a scientific subject like radiation oncology or quantum mechanics, the boundaries of cultural movements are fuzzy, the definitions blurred. We think we know what Modernism means, because by common agreement it's over. What Postmodernism means is far less clear, because that's what we think we are having, at present. One eminent scholar of these things was recently driven to give up on Postmodernism; for him, it was just intellectually half-baked.

Modernism seems to define the cultural turmoil provoked by the Industrial Revolution for most of a century, 1880 to 1950. It's distinctive, perhaps defining, characteristic was a constant search for novelty. Why did Modernism come to an end in 1950? Well, because that's when Postmodernism began. The Industrial Revolution didn't stop in 1950, so although it may have provoked Modernism in art and culture, it wasn't enough to sustain it.

Our grandchildren will have to tell the world the final definition of Postmodernism, but at the moment it is thought to represent an artistic tendency to blur the real and the unreal. Some have suggested it was provoked by the Information Revolution, but that came two decades later. A social and economic upheaval with better timing is the rise of the American Century. After Europe committed suicide in World War II, only America was left standing. The thought processes of the Austrian school of Economics, led by von Mises and Hayek, relocated to the University of Chicago, triggering a long string of Nobel Prizes in Economics. Application of mathematics and measurement relentlessly demonstrated that previously undisputed doctrines of Marx, Keynes and other heroes of the left -- were probably just plain wrong. The new Holy Grail was a rising tide raising all the boats. Don't argue with the tape. Marxism is now a discredited response to the industrial revolution, but the art world is equally mistrustful of supply-side economics and other murky mysteries. Certitude is gone; how do we return to the light?

It isn't easy to discard the beliefs of a lifetime. When you do, it affects the way you think about a lot of other things. And it takes a long time for equations and mathematical models of economics to reach out to the world of the liberal arts. For lack of a better explanation for Postmodernism, I suggest that at least the timing of this explanation seems about right.

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing

|

| Statue of Diana |

The brownstone house at 1710 Spruce Street is seemingly not remarkable, it's just an Edwardian house now converted to lawyers' offices on the first floor. But it's nevertheless a landmark, curiously linked to that 13-foot statue of Diana which dominates the top of the main interior staircase of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Many Philadelphia gossips believe the model for the statue was Evelyn Nesbit, who lived in the brownstone on Spruce Street. But she was born in 1884, whereas Augustus Saint-Gaudens created the statue for the 1892 Columbian Exhibition. Since Evelyn was only eight years old at that time, however, it must have been some other woman who took off her clothes to pose for the sculpture; for us, it doesn't matter who she was. The statue was moved to the top of Madison Square Garden when that structure was really still located on New York's Madison Square, but when the Garden was demolished in 1925 the Diana statue came to Philadelphia. Madison Square Garden itself has moved twice in the meantime and is mostly associated in the public mind with prize fights and political conventions. However, when the first Garden was built, it had theaters and roof-top restaurants, and its spectacular nature instantly made the architect, Stanford White, the most famous architect in New York, eventually maybe the most famous one in the world at the time.

|

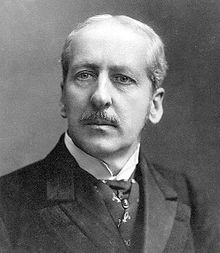

| Thaw |

Meanwhile, two residents of Pittsburgh independently came to New York where the action is, the iron and coal millionaire Harry K. Thaw, and an impoverished teenager named Evelyn Nesbit. Evelyn was accompanied by her mother who, recognizing the girl's extraordinary beauty, set about to steer her to fame and fortune. At the age of thirteen she was posing for artists, and in time became the favorite model for Charles Dana Gibson. Gibson created the "Gibson Girl", an idealized role model for millions of women who dressed the way she did, wore their hair the way she did, and behaved in the proper Edwardian style they imagined she did, too. It was in Gibson's studio that she encountered Stanford White. Evelyn had another life, however, as a "Florodora Girl", and one of her many stage-door Johnnies was Harry K. Thaw, the millionaire. That was no saint, having a reputation for using a dog whip on his numerous lady friends, but it is uncertain whether he was completely aware that

|

| Evelyn Nesbit |

Evelyn was one of the principle entertainers in half a dozen hide-aways that Stanford White is said to have established for naughty parties to amuse New York's fast set. That was certainly aware that Stanford White had been Evelyn's boyfriend before Thaw married her, and the two men cordially hated each other. One evening, some provocation made Thaw walk over to White's table in the rooftop restaurant of Madison Square Garden, and shoot him dead -- in front of hundreds of people. It's a curious sidelight that Stanford White was carrying a train reservation to Philadelphia, to discuss plans for the domed structure of the Girard Bank building. The notoriety of the murder trial was the sensation of the decade, with the prosecutor remarking that White deserved what he got, and Thaw's mother offering Evelyn a million dollars if she would give testimony supporting a plea of insanity. Everyone seems agreed that the money was never paid, although the jury was sure as impressed as the newspaper reporters with Evelyn's refusal on the witness stand to testify against her husband, quite evidently a sign of loyalty. Anyway, the jury let him off, and a famous cartoon depicted Stanford White in the pose of the statue of Diana.

|

| Joan Collins as Evelyn Nesbit "The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing" |

Evelyn sort of dropped out of sight after the trial and the subsequent divorce, until TV interviews were conducted for the movie about the episode, \"The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing". By 1957, Evelyn was decidedly less of a beauty. Meanwhile, Harry K. Thaw had continued to live in the brownstone house in Philadelphia, where once he got sick and called a friend of mine to be his doctor, and eventually another famous professor to be a consultant. When the butler answered the door, the consultant told the butler to tell his employer that he must insist on cash in advance, an action that thoroughly embarrassed my friend in view of the famous wealth of the client. But the consultant had rightly assessed the situation since later Thaw's lawyer called up and told the family doctor he was sorry but his client was not going to pay his bill since the medicine was started by some botanical book to be a poison in excess quantity. In consternation, my friend called up the professor and asked what to do. "Chalk it up to experience," was the answer. "But what have I learned?" The consultant paused, and said, "Maybe you have learned to extend credit only to decent people."

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

|

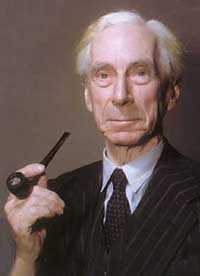

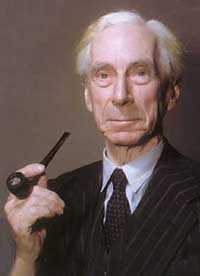

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

The Barnes Foundation: Comments on the Economics of Art (2)

In 1951, Albert C. Barnes' legacy included Jerome's Epistle to Paulinus from the Gutenberg Bible education centered on a notable collection of illustrative artworks, housed in a museum of his own general design for the purpose. He left a multi-million dollar endowment to support his rather detailed and, in the opinion of many, somewhat eccentric intentions. It was his money, however, so his word was final. The institution was fairly mature, having previously been in operation under his direct control for twenty-five years.

Since the Foundation trustees are now before the Orphans Court pleading for permission to modify Dr. Barnes' instructions in order to avoid financial collapse, skepticism is inevitable. Obviously, the successor trustees must explain their expenses. But quite a plausible case can be made that the true cause of this disaster is inherent in the huge windfall growth in value of the paintings. In short, growth in value of the fine art may have outstripped the growth of the resources set aside for maintenance.

|

| Johann Gutenberg, creator of mass produced books, died in poverty |

Let's make a benchmark of the Gutenberg Bible, where incomplete copies are currently selling for $100,000 a page and complete copies are estimated to be worth $100 million apiece. Dealers maintain the Gutenberg is increasing in value at 20% a year, but growth seems closer to 9% a year if you go back to 1951. What's really relevant here is the growth in cost to ensure, protect, dehumidify, display and make it available to scholars, if not the public. It seems safe to guess these maintenance costs have grown more rapidly than the investment growth of the endowment, which is surely closer to 4% than 20%. The imbalance is even greater if you remember that some investment income is spent every year, while the worth of the fine art just grows and grows. Regardless of the true numbers, if the cost of maintaining the art does grow even slightly faster than the endowment, the dilemma the Barnes is now facing will eventually face any museum. New sources of revenue, either from the government or from public admissions, eventually becomes necessary if the priceless art remains on display. It is displaying these things that cost money; burying them under an Aztec mound or a German salt mine shelters them from the problem. In the case of Alfred Barnes, it is not completely certain that he wanted them displayed.

There is also the issue of quirky fluctuations in the market for fine art. The 22 known perfect copies of Gutenberg, Bibles have been around for almost five hundred years, and it is safe to say their value is enduring. The 180 paintings by Renoir now owned by the Barnes may prove to be Gutenberg Bibles or they may prove to be a passing fad, but it is pretty hard to believe that one of them will always be worth two Gutenbergs. Since there is a pretty fair chance that we are currently seeing a value bubble in French Impressionist painting, it is questionably prudent to shipwreck the whole Barnes Foundation, the School, or Albert C. Barnes basic intent, by resisting the sale of even one of the more overpriced examples in the collection at the top of the market.

That's one side of it. Another consideration is that Barnes himself did considerable merger negotiation with other museums, and may have been unexpectedly killed in an auto accident before he turned over all his cards in that particular poker game. It's asking a lot of the poor judge to overturn the clear and largely unmistakable language of Barnes will in favor of theories about what Barnes was really really thinking when he wrote it. If the judge is feeling adventurous, it's probably more satisfying to all parties if he sets forth a new legal doctrine, reflecting the inevitable disparity between the cost of displaying fine art to the public, and providing a perpetual endowment to do so.

Edward Hicks: Peaceable Kingdoms

|

| Peaceable Kingdoms |

Edward Hicks (1780-1849), the most important folk artist of American art, was born and lived all his life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. About a hundred of his paintings survive, 62 of which are versions of "The Peaceable Kingdom". Recently, his Peaceable Kingdoms have been selling for more than $4 million apiece, and the other works at more than a million. As is so often the case, he was born in poverty and spent his life in poverty, so the financial benefits have all gone to middle-men.

Hicks had to overcome an additional handicap. Quakers disapproved of painting things up just for show, and they strongly disapproved of the vanity underlying the act of having a portrait painted of yourself. In fact, the early Quakers would not even permit their names to be placed on their tombstones.

Hicks was apprenticed into the wagon business and showed a talent for painting them. From that, entirely self-taught, he migrated into the business of painting business signs in an age of limited literacy. The Blue Anchor Tavern, the King of Prussia Inn, the Crossed Keys Tavern and the signs of various tradesmen were an essential part of conducting business. It is easy to see these tradesmen signs in the easel paintings of Hicks' later career, which reduce themselves to rearrangements of such individual sign paintings to make a coherent canvas.

If you have seen one "Peaceable Kingdom" you haven't seen them all, but you only need to see one to be able to recognize the others at sight. They generally form a group of wild animals and an occasional child in the right foreground, with a grouping of Quakers and Indians in the left background, taken from Benjamin West's famous portrayal of Penn signing the treaty of peace with the Delaware Indians. The scene is taken from Chapter 11 of Isaiah, in which the lion lies down with the lamb.

Hicks was not a successful farmer, and he had to overcome Quaker resistance even to sell religious paintings with a Quaker moral. No doubt the resistance was strengthened by the fact that his cousin Elias Hicks had split the Quaker church into two (Conservatives and Hicksites) in 1827, and Edward was himself a strong itinerant preacher. Although the plain message of the Peaceable Kingdom is reconciliation between the two branches of Quakerism, he probably encountered a fair amount of coolness among the Conservative opposition.

Hicks was neither an educated nor a sophisticated man. It is forgivable that he made such a strong Old Testament statement when he and his cousin represented a dissenting sect that was gravely doubtful about the wisdom of allowing your life to be ruled by biblical verses.

Billy Penn's Hat

|

| Billy Penn's hat |

Philadelphia City Hall was intended to be the tallest building in the world, so there was no reason to suppose anything in Philadelphia would be taller. Gradually, taller buildings in other cities were built, but there grew up a gentleman's agreement that no skyscraper would be built in Philadelphia that was taller than William Penn's hat atop his statue on the tower of City Hall. Planning in the city was organized around this premise, which affects subways and other transportation issues in the city center. Because of assassination fears, a similar tradition in Washington DC was enacted into law, and it must be admitted that the flat skyline of that city looks a little dumb and boring. But Philadelphia neglected to pass a law, and so at the end of the Twentieth Century first one and then half a dozen skyscrapers were built that were twice the height of City Hall, immediately destroying the organizing visual center of the city. Pity.

But there are more serious issues involved. Aesthetics aside, who cares if someone bankrupts himself building an inappropriately tall building, with excessive elevator costs, problems with reinforced foundations, shortage of parking space, and the like? And the answer to that is the new tall building will bankrupt the older office buildings, not itself. Using offers of low, low rents to fill the new building, tenants will be drained from other spaces, and other areas of the city will deteriorate unless there happens to be a general shortage of office space in the region. Carried to an extreme, all of the center city business might be envisioned to reside in one thousand-story building, and the rest of the region would be a desert.

The obvious response would be that no landlord wants to have competition, and new construction is the way a city renews itself, creatively destroying the old to make room for the new. You must not allow the vested landlords to capture the political process with agitation if not bribes. Push things too far in that direction, and you will find that political corruption has destroyed the fabric of the town more effectively than a couple of skyscrapers ever could. Market East has been devastated, it is true. But that's the price of conducting the commerce of the region on the basis of market economics instead of through bureaucracy which masks corrupt politics with high-flown language. Paris is beautiful, but France has 12% unemployment which is closer to 16% if you remember the 30-hour week, the nine-week vacations, and retirement age in the fifties.

And yet, there is certainly a point to be made here. The height limit on new construction must bear some relationship to the regional need for new office space, and not merely rely on beggar-my-neighbor. We're currently hearing about two new projected skyscrapers, one beside 30th Street Station, and the other at 17th and Market/Chestnut. The decision to go or no-go will rest with whether the developers can find "lead" tenants. The corporate officers of these large enterprises are the ones who must be expected to give careful consideration to the best interest of the community because right now they are the ones who control matters. If they neglect their responsibilities, the pressure to pass more zoning laws will prove hard to resist.

Laurel Hill

|

| Laurel Hill Cemeteries |

There are two Laurel Hill Cemeteries in Philadelphia, sort of. Although both are described as garden cemeteries, the older part in East Fairmount Park is more of a statuary cemetery or even a mausoleum cemetery. When its 74 acres filled up, the owners bought expansion land in Bala Cynwyd, which could come closer to present ideas of a memorial garden. Particularly so, when the older cemetery area started to fill in every available corner and patch and began to look overcrowded. The name was used by the Sims family for their estate on the original area. Since June-blooming mountain laurel is the Pennsylvania state flower and a vigorous grower, it seems likely the bluff overlooking the Schuylkill was once covered with it. Somehow the May-blooming azalea has become more popular throughout the region, particularly in the gardens at the foot of the Art Museum. If extended a little, merged with laurel on the bluff, and possibly with July-blooming wild rhododendron, there might someday arise quite a notable display of acid-loving flowering bushes from the Art Museum to the Wissahickon, continuously for two or three months each spring.

There are interesting transformations in the evolving history of cemeteries, best illustrated in our city by the traditions of the early Quakers when they dominated Philadelphia.

|

| Thomas Grey |

Objecting to the ornate monuments which Popes and Emperors erected for their military glory, and probably to the aristocratic custom of burying important people inside churches where they could be worshiped along with the stained-glass saints, early Quakers were reluctant to mark their own graves with headstones, or even to have their names engraved on such "markers". By contrast with the splendor accorded aristocrats, the common people in Europe were largely dumped and forgotten, providing an unfortunate contrast. During the early part of what we call the romantic period, Thomas Gray popularized these attitudes in Elegy in a Country Churchyard. To be fair about it, the early Christian Church had a strong tradition of collecting the dead of all classes into catacombs. The Romans were quite reasonably upset by the potential for spreading epidemics through people living within such arrangements, although feeding the Christians to the lions seems like an overreaction.

At any rate, and to whatever degree the French Revolution was what shattered previous traditions, the Victorian or romantic period produced a new vision: garden cemeteries in Paris.

|

| George Mead |

The concept soon spread to Laurel Hill, and thence to the rest of America. Acting with what probably had some commercial motivation, cemeteries then moved away from churches to suburban parks, promoted as places of great beauty in which to stroll and hold picnics, perhaps to meditate. The private expense was not spared in statues and mausoleums, which often became display competitions between dry goods merchants and locomotive builders. Revolutionary heroes were dug up from their original graves and transported here to be more properly honored, as were some private persons whose descendants wished for more suitable recognition than conservative church rectors had offered. The Civil War created the staggering number of 632,000 war dead; based on the proportion of the population, that would be equivalent to six million in today's terms. Since they were almost all male, there must have been at least a half-million surplus women as a consequence. The nation and this almost unbelievably large cohort of single women had an impact on society for thirty or forty years after The War. Eventually, this would lead to colleges for women, suffrage and other forms of feminism, but the initial manifestations of what we now call Victorianism took the form of formalized grief, particularly the 75 National Cemeteries of crosses row on row. But private initiatives also took a variety of forms, including Laurel Hill's statuary to honor the valor of the fallen, ranked by the number of generals buried there and visits by sitting Presidents of the United States. Laurel Hill, East, holds 42 Civil War Generals. It will be recalled that Lincoln's Gettysburg Address was delivered at a much larger final resting place for fallen soldiers, but Laurel Hill had the generals, including George Gordon Meade, himself. It is probably significant that Laurel Hill West, three times as large, was opened in 1867. At the headstone of each Civil War veteran is found a metal flag-holder, put there by the Grand Army of the Republic and marked with GAR surrounding the number 1. This is the home of Post Number One, the Meade Post, the original home of this organization responsible for many patriotic movements like the Pledge of Allegiance and commemorative reunion encampments and reenactments. The main purpose of the war was to preserve the unification of a continental nation, and the GAR sought to raise patriotic consciousness to a point where fragmentation would never again be conceivable.

|

| John Notman |

Two names stand out in the history of these cemeteries, Notman and Bringhurst. John Notman was one of the early architects who fashioned the look and feel of Philadelphia. His identifying feature is brownstone, as seen cladding the Athenaeum building on Washington Square, and St. Marks Episcopal Church at 15th and Locust. At Laurel Hill, the main entrance confronts a brownstone sculpture by Notman of "Old Melancholy", depicting a typical Victorian romantic vision; just about all other monuments in the cemetery are either of acid rain-eroded marble or indelible granite. Brownstone from Hummelstown PA provided the characteristic look of New York residential architecture during this era. Philadelphia brownstone probably came from the same place. The other name is Bringhurst, dating back to 17th Century Germantown, long associated with the underlying sanitary purposes of the cemetery. The family finally and gladly sold the undertaking business a few decades ago.

Somehow, the image of cemeteries has now transformed from public places of meditation and reverence to places that are "spooky". Their greatest surge of visitors, these days, occurs at Halloween.

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Donor Intent

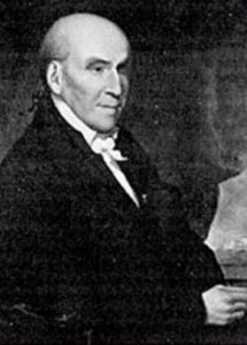

At least three of the greatest treasures of Philadelphia are now used in ways that almost certainly flout the expressed wishes of the donor. Steven Girard's

|

| Alfred Barnes |

bequest for the enhancement of "poor, white, orphan boys" is now devoted mostly to black children, many of the girls, many of them non-poor by some definitions, and many of them orphans only in a limited sense. Alfred Barnes wanted his art treasures to be used for education, outside the city of Philadelphia which had offended him, and definitely not part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art which he disliked. They are now to be moved to Philadelphia's Parkway, close to and under the thumb of, the Philadelphia Museum of Art. John G. Johnson's immense art collection now resides within the Museum of Art in spite of the firm declaration by this eminent lawyer that it was to remain in his house, and definitely not to be used to promote some huge barn of a museum.

|

| William J Duane |

It's hard to imagine how any set of instructions could be devised to be more clear than these. Barnes employed a future Supreme Court Justice, Owen Roberts, to write his will. Girard similarly employed the preeminent counsel of his time, William J. Duane, to devise an extraordinarily detailed set of instructions. John G. Johnson was himself considered to be the most eminent lawyer in the city. In fact, he once received a fee of $50,000 for his opinion about a corporate financial plan, consisting of the single word "No" scrawled on its cover.

It would be interesting to know whether these famous cases are typical of the way wills are treated, either in this city or in the nation generally. Perhaps they are notorious mainly because they are so unusual. But perhaps they are indeed rather representative and stand as lurid examples of the general failure of the rule of law. Perhaps they reflect some deeper wisdom of the law, where Oliver Holmes intoned that the standard was not logic, but experience.

<Perhaps some guidance can be found in the decisions of Lewis van Dusen, Sr. who for several decades established the Orphans Court of Philadelphia as a model for the world to follow. Someone seems to have thought he set a good example. But was his reign an exception, or a glowing example of the triumph of society's wisdom over the crabbed grievances of dying millionaires in their dotage?

These remarks are made while the newspapers are filled with the story of a Texas billionaire who married a magazine model fifty years younger than himself. Some prominent local heiresses are known to have run off with their stable boys. Indeed, you don't need to read many tabloids to see a dozen examples of such behavior. Is it possible that some of them were acting up out of frustration at the probable betrayal by the courts of more reasoned instructions for their wealth?

Wall Art in Philadelphia

|

| Seasons |

At last count, Mural Arts program of the city government of Philadelphia has sponsored and paid for 2700 large paintings on the walls of buildings around town, and several hundred more have appeared spontaneously. Comparatively few art museums have that many on display, so people are proud of the Philadelphia effort.

This program is now nearly thirty years old, beginning to emerge as a national treasure. Looking back, it is pleasing that it had humble, even deplorable, origins. As American cities lost their industrial focus, many homes in the neighborhood of former factories have been abandoned, getting torn down in random patterns. Industrial cities of the East Coast were tightly packed to save land costs and time commuting to work; the fashion of "row houses" evolved without any space between neighbors sharing a "party" wall. When a row house was torn down, there emerged a scabrous ghost, because the wallpapered interior walls were exposed and looked pretty hideous. It eventually became illegal to leave a scabrous building, leading to elaborate legal conventions about responsibility for the cost of covering exposed surfaces with concrete stucco. During the last half of the Twentieth Century, stucco was generally an improvement.

|

| Graffitti |

Meanwhile, during World War II it became clever for American military to inscribe "Kilroy was here" on unprotected public surfaces at home and abroad as a gesture of American triumphalism. Opinions differ about whether this started originally as an allusion to a certain line of 19th Century romance poetry, or whether there was in fact a John J. Kilroy, inspector of riveting in wartime shipyards, marking riveted materials with his name to enable piecework payment for shipyard tasks. Eventually, this Kilroy joke became a little tiresome, but soon was replaced by stylized decorations using cans of spray paint, until "graffiti" painting, in turn, became a public nuisance. It is true some graffiti artists were quite talented, but the associated vandalism of teenagers added a threatening quality to public defacement of property belonging to others. By implication, an area with graffiti was a home of lawlessness and that implication cast a negative shadow on the city economy. Public opinion demanded something effective be done to stop it.

|

| Frank Sintra |

Since graffiti vandalism has declined nationwide in the past twenty years, it is difficult to claim that one public initiative in Philadelphia cleaned it up. But it might be true. Then-Mayor Wilson Goode formed an antigraffiti Network, essentially a think tank for concerned citizens, floundering about for a solution to an appalling problem. Somehow the inspired idea arose that the graffiti artists might be channeled into better directions if given professional art lessons, and working materials. A West-Coast artist named Jane Golden was hired to supervise what has become a multimillion-dollar project, overseen by some sort of guiding hand pushing the whole city into becoming part of a gigantic art project. Guides tell visitors that there are fifty employees involved in publicity and legal work, organizing artists, fundraising, organizing teams of painters at all levels of competence, helping oversee the general appropriateness of what is happening. And at the head of this team is Jane, a tornado of energy.

|

| Frank Rizzo |

It costs forty to seventy thousand dollars to produce one of these works, and since they are exposed to the weather, they only last about fifteen years. There are several techniques for transforming a small artwork into a big outdoor copy, some of them tracing back to Michaelangelo. Most of the Philadelphia murals are produced by dividing the original small artwork into squares and transferring numbered squares to the wall, one inch to one foot. As you can see by reviewing some of the websites devoted to the topic, a piece of art which is quite appealing can sometimes change into a drab mess when its size is blown up to three-story height. The problems of lighting such work are quite different from the lighting of a gallery painting. The surface is seldom smooth, so the bumps and grooves of the underlying scabrous "canvas" can destroy, or sometimes dramatically enhance, a salon painting. If you get too close, you can't see all of it, and that may be a problem. It's probably not entirely predictable what will come out in the final product.

There are inevitably political problems as well. The best examples are the several paintings of former Mayor Frank Rizzo, who is a hero to the Italian neighborhoods where they stand, but provoke riotous feelings in near-by black districts. Luck alone has confined the antagonisms to graffiti on the murals, viewed by some groups as enhancements on what begins as graffiti. No wonder the committees assigned to approving locations can take a long time to come to a decision.

There's another problem, which seems to be embedded in the situation. In the central city skyscraper district, you don't have scabrous buildings. Nor can mural art be placed in the historic square mile. Just a few blocks in either direction from central city there are plenty of demolitions and scabrous walls, but, close to downtown, these are areas of gentrification and urban renewal. It doesn't make sense to spend fifty thousand dollars to paint a wall which will be demolished in two or three years. The net effect is that the city may have three thousand paintings all right, but only fifty at most are within a tourist ride of Independence Visitors Center. If half of these fifty are concerned with celebrating local heroes unfamiliar to tourists, there can be disappointment which would disappear if a selection of fifty outstanding products could be culled from three thousand -- and grouped together for exhibition.

A solution to these issues will surely emerge with time, but it will evolve, not be envisioned.

The University Museum: Frozen in Concrete

|

| King Tut |

Recently, a charming archeology scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, Leslie Ann Warden, entertained the Right Angle Club with the interesting history of King Tut. Interest in this subject is currently heightened by a traveling exhibit of the tomb relics currently on elegant display at the Franklin Institute. However, Philadelphia also has a permanent exhibition of Egyptian artefacts lodged in the University Museum. Since this museum is the second largest archaeology museum in the world, after the British Museum, that makes it the largest in America. An interesting sidelight is that Ms. Warden spoke in the grill room of the Racquet Club, which was the first effort by William Mercer to use "Mercer" tiles in a building. Mercer at that time was the curator of the University Museum. We learned from Ms. Warden that King Tutankhamen was unknown before his tomb was discovered, all records of this part of the Egyptian dynasty having been lost or deliberately obliterated by successors. Therefore, the discovery of these magnificent art objects started a massive expansion of scholarship about the entire Third Millenium.

|

| William Pepper |

The establishment of the University Museum around 1890 was apparently mostly due to the enthusiasm of William Pepper, then Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. What seems to have got Pepper going was an expedition to Iraq, the place where civilization began, in Mesopotamia. The relics brought back from this celebrated effort needed a home, and Pepper decided it had to be here. One famous philanthropist after another, often in the role of Chairman of the Board of Trustees, carried on the tradition after Pepper's premature death. Some of them have their names on buildings, some declined. To a notable degree, the feeling of special possession was exemplified by Alexander Stirling Calder, who turned the statues in the garden to face inward rather than out toward the street. Asked whether a mistake had been made, he is said to have replied that due to the Museum's withdrawn character, it was more appropriate for the world to face the Museum. No more icily accurate comment has ever been made about the University's relation to its city neighbors.

The real knock about the Museum is that too much has been crowded into too little real estate, and the fault lies with the automobile. After the University outgrew its space at 9th and Market around 1870, moving then to West Philadelphia, the architects and the donors originally envisioned a grand boulevard of culture stretching from the South Street bridge many blocks westward. The Museum, Franklin Field, Irvine Auditorium, The University Hospital were to be the start of an imposing array of culture. Unfortunately, that was a horse-drawn conception, soon to be overwhelmed by the worst traffic jam in the city. The Schuylkill Expressway was the final blow, setting huge auto-oriented structures in place where their easy removal became difficult to imagine. The 1929 stock crash, followed by confiscatory income and estate tax rates, merely emphasized the plain fact that restoring the grand vision was beyond the ordinary aspirations of even massive private wealth. Transforming the imposing plazas of the University Museum into parking garages was probably a result of excessive despair, but if you have ever tried to find a place to park in that region you can somewhat sympathize with the small-mindedness which prompted it. Bringing back this region is going to require immense vision and resources, neither of which is exactly thrusting itself forward at present. So, unfortunately, one of the central cultural jewels of the City is buried in the midst of an impenetrable thicket of concrete and speeding automobiles, too big to move, too small to burst its bonds.

It's well worth a lot of anybody's time, and many visits. If you can find a way to get there.

Laran Bronze

|

| World War II Memorial |

Bronze is the term for alloys of copper, most often mixed with tin, aluminum or whatever in varying proportions. Although the Bronze Age was one of the earliest stages of civilization, most of us would still have a hard time even stating the proper mixture of metals we might need to manufacture some bronze object for some particular purpose. No doubt Alexander the Great and his friends just stumbled on a mixture suitable for swords, helmets, and shields, but nowadays we expect a little more precision than that. So, go visit the engineers and artisans who occupy a whole block of downtown Chester and discover where the engineers take over from the sculptors. For example, the bronzes of the World War II Memorial in Washington were fabricated here, eventually bringing the final bill for the Memorial to $197 million. Whatever Laran may be, it isn't cheap.

|

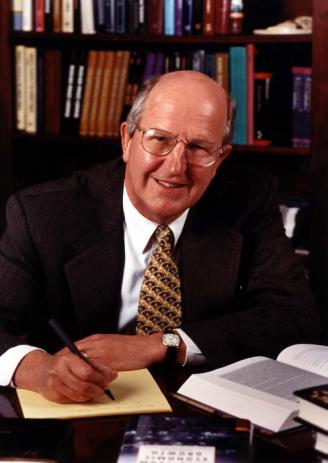

| Andrew Carnegie |

Because of the size and weight of monumental bronzes, there is a tendency for bronze fabricators to be chosen in the general neighborhood of the permanent site of the statue. Even so, most large pieces are cast in smaller pieces and welded together at the site. Because that leads to more external struts that have to be trimmed and smoothed out, and more welding, there is a constant struggle to improve the technology to eliminate chop-ups. However, the bigger the piece, the harder it is to support with internal steel struts, so there is a constant process of re-engineering which is considerably under-appreciated. Since Larry Welker the proprietor of this operation went to Carnegie-Mellon, it brings up an analogous situation in steel fabrication. Andy Carnegie is mostly remembered for giving away libraries and mistreating his employees, but in fact, his achievement was an engineering one. His steel mills were four times as productive and efficient as his nearest competitor (Krupp of Germany). That not only made him the richest man in the world, it also made it possible for America to defeat Germany in World War I, and eventually become the dominant superpower.

Since sculptors are in a position to designate the bronze fabricator of their work, it would be wise for the fabricator to be nice to sculptors. However, computers have stuck their nose in this business, as they have in most businesses. A sculptor ordinarily makes a small model whose image is scanned into a computer and then blown up to final size. From this, a positive mold is made, from that a negative mold, and from that, the final positive bronze shell is cast. But once you pass that image through a computer you open up the possibility of synthetic images made through the mechanisms that make animated movies; and maybe eliminate the need for the sculptor entirely. That prospect naturally displeases sculptors, as does the potential for counterfeiting and exporting jobs.

Just about everything about bronze sculpture revolves around its massive weight. That's why bronze statues are typically hollow but carried too far, the statue can't support its own weight and must have internal steel struts. The internal struts are mainly stainless steel, often encased in the plastic sheathing. The molds which make these eggshells are generally made of ceramic, which is melted sand. The process starts with wax coatings, often a quarter-inch thick dipped in fine sand, then a layer of coarse sand finally baked into ceramic. That's the negative mold; the positive mold from which it is made starts with wax, covered by latex, covered by plaster of Paris. Since a lot of steps don't come out perfectly, they have to be repeated. All in all, it becomes convincing that spending $197 million for a war memorial is entirely legitimate, because we haven't even described the costs for the artist at one end of the process, and the appalling transportation issues at the final step.

Although the WWII Memorial isn't even in Philadelphia, it's surely worth a trip to Washington to see what Philadelphia can do. While you are there, look for the "Easter Eggs". That's the term for humorous images hidden by the artist within the serious larger object. This too is a tradition going back to ancient times; in the case of the War Memorial, the artist hid images of at least one soldier "goofing off" in each freeze. Perhaps even that could be done by computer, but it's harder.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1291.htm

Quilts, Patchwork Style

Although quilting can be found in the tombs of ancient Egypt, American farm women are correct that they invented an art form.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

In the days when transport was primitive, art forms were invented in many places at once, mostly responding to new materials and new technologies. It's irrelevant to the genius of creation, for archivists to pounce on evidence that an art form surfaced a decade or two earlier in one place than another. Creative art could easily have been -- and often was -- invented by five or six people in different regions, each with a just claim to inventing without copying. In the case of quilts, there is a semantic wrinkle, too. If you define quilting as the process of anchoring three layers of cloth together with stitches, then quilts have been found in ruins of ancient China and ancient Egypt. The underlying principle was that three layers of cloth were warmer and stronger than single sheets of cloth or animal skins, so quilting was used for shoes, pants, jackets, and underneath suits of armor. Mary Queen of Scots spent a lot of time in confinement, and examples still survive of tapestries she made with the quilting process. None of this is what American farm women mean when they say that "quilts" are an American invention, and a new art form.

|

| Quilt, Patchwork Style |

What they mean is patchwork-quilting of bedspreads or counterpanes. To make that specific kind of quilt, you pretty much have to wait for the industrial revolution to provide decorated cotton cloth, then for it to become cheap enough to be used as sacks for flour. That attracts frugal farm wives salvaging material for dresses and shirts, and later re-salvaging pieces of it for patches. Somewhere the idea caught on that decoration was needed for the tops of beds; if these ornaments were usable for extra warmth it was even better. And so, we got patchwork counterpane quilts, incorporating different colored patches into designs. They start appearing around 1750 but gained real popularity around 1830. Since no one was keeping records, it's hard to know if the common diamond design was an outgrowth of the Scotch-Irish street "diamond", or an outgrowth of the hex signs which are commonly believed to have originated in the monastery in Germantown. The path of westward migration would have carried such traditions to the rest of the country, so this analysis has some plausibility. However, the ideas are so simple it would surely be impossible to trace them. What is so unique about this folk art is that the design can be oriented around a piece of a favorite grandparent's shirt or dress, evoking that person's presence and personality in a manner largely incomprehensible to anyone except the immediate family. This intimate quality is easily lost, even in third and later generations of the family, although family traditions can be maintained in the designs and by hearsay.

There may be other traditions of folk art evoking a particular individual who is unrecognizable to outsiders. They might admire features of the design but have no way of knowing the personality of the person celebrated, or making associations with the piece of cloth. But this quilt art becomes established as a family heirloom as almost nothing else could be. Its sweetness is oblivious to the fashion police who contribute a rather aggressive undertone to so much of the art world. For example, in the period between the first World War and the Korean War, it was just about impossible to have a non-modernist painting accepted for a juried show. The same juries who enforced such competitive dictates seemed to forget they denounced the "conservative" academics who excluded impressionist painting a century earlier. During the modernist period, disk jockeys and band leaders likewise serially enforced the various fashions of jazz music; classical music was totally banished. Book reviewers, now a dwindling race, similarly laid down standards of obedience for authors and playwrights on behalf of a style now commonly praised as "liberal". Publishers and producers defied such dictates at their peril, and now must reorient to the coming new standard, called post-modernism.

By contrast, the isolated troubadours of home quilting artistry continue to create as they please, primarily speaking to their families and selling a few less treasured products -- to uncomprehending strangers.

Furniture for the Horse Country

|

| Douglas Mooberry |

Low-end furniture for America is now mostly made in China, and seldom made of wood. Truly American cabinet making tends to be high-end, and high priced. That tendency goes to some sort of extreme around Unionville in Chester County, where a 25-year old company named Kinloch Woodworking holds pride of place. The owner, D. Douglas Mooberry, picked the name Kinloch at random from a map of Scotland, but his selection of southern Chester County was not an accident. The influence of nearby Winterthur has infused that whole region with an interest in fine furniture craftsmanship, and museums like the Chester County Museum and others throughout the nearby Pennsylvania Dutch country provide an ample source of authentic pieces to serve as examples. There's one other factor at work. As Doug Mooberry quickly noticed, people with money usually have lots of it. There really is a market for $28,000 tall case clocks, $18,000 highboys, and $12,000 tables -- if you can convince people in Chester County you are really good.

Although this 12-person company repairs antique pieces, it does not make exact reproductions. It produces new pieces in the old style of the region, based on careful analysis and evaluation of museum pieces from earlier times. Kinloch once aspired to equal the quality of the early artisans, but now aspires to surpass them in quality of materials and workmanship. The more conventional stance of fine artists is to attempt to excel in today's current style, whatever that may be, probably "post-modern". Kinloch artists, however, choose to excel in the style of a long-past era, taking care not to claim the product is antique. Artisans grow up in cooperative clusters; there's a world-famous veneer company nearby and a pretty good hardware company, although the best craftsmen of furniture hardware are still found in England.

|

| Chippendale Table |

The characteristic style of Chester County furniture in the Eighteenth Century was a mixture of two neighboring cultures, Queen Anne, Chippendale, ball and claw Georgian style of Philadelphia; and the "line and berry" inlay style of the Pennsylvania Germans. If carefully executed, this hybrid style can be very pleasing, and you had better believe it requires painstaking craftsmanship. Others will have to explain the significance or symbolism of intersecting hemi-circles in the lines, and the inlaid wood hemispheres, the berries, at the end of the lines. But the technical difficulty of laying strips of 1/16 inch wood in curved grooves only a thousandth of an inch wider, or the matching of 3/8th-inch wood hemispheres into hemispheric holes gouged out of the main piece -- making the surfaces of the inlays perfectly smooth -- is immediately obvious to anyone who ever tried to whittle. Ultimately, however, true artistry lies in combining two unrelated styles without producing an aesthetic clash. By the way, you would be wise to wax such furniture once a year.

The factory is on Buck and Doe Run Road, and here's another culture clash. At one time, Lammot du Pont cobbled a 9000-acre estate out of several little country villages. In 1945 it was sold to the Kleberg family of Texas, the owners of the King Ranch. Robert Kleberg was an admiring friend of Sam Rayburn but treated the oafish Lyndon Johnson as his personal political gofer. From 1945 to 1984 Buck and Doe was used as one of several remote feedlots for Texas Longhorns bred to Guernseys, the so-called Santa Gertrudis breed. Originally, Texas cattle were seasonally driven to Montana for fattening, then on to railheads for the stockyards. As farmers began to build fences interfering with the long drive over the prairies, it became cheaper to fatten cattle closer to the markets. So satellite feedlots like Buck and Doe Run were developed. You can pack more cattle in a rail car when they are younger and smaller, and advantage can be taken of price swings by suppliers who are close to the market. In this case, the markets were in Baltimore. Since the King Ranch is larger than the state of Rhode Island, such 9000-acre farms were pretty small operations in the view of the Texas Klebergs, an opinion they did not trouble to conceal from the irritated local gentry. The point was even driven home in high society circles by holding large parties at Buck and Doe Run, allowing guests to wander around the roads, unable to find the house of their host even though they had been on his property for most of an hour. In 1984 the Buck and Doe was sold to Art DeLeo, who is busily converting it into a nature conservancy.

Beaux Revival

|

| Cecilia Beaux |

Cecilia Beaux's mother died two weeks after she was born. Cecilia rejected many offers of marriage, was never brushed by scandal, devoted her life almost entirely to the pursuit of excellence as a portraitist of women and children. It does not take much of an amateur psychoanalyst to surmise she was dominated by fear of pregnancy, and possibly guilt about being the cause of her mother's death. But living in the Victorian era before Lister and Pasteur could finally make childbirth safe, her sort of life was not as unusual as it is today, except for her notable thirst for achievement. An aristocratic upbringing almost certainly contained a strong condemnation of boasting and self-promotion, with the result that she is sometimes referred to as a perfect model for the graduates of Bryn Mawr College, although she did not attend there. Placing its emphasis on success for women other than or in addition to marriage, the quiet determined graduates of that college make a goal of achievement, not fame. Beaux became the finest woman portraitist in America, possibly the finest portraitist anywhere, but it was a title she earned and deserved without theatrics or egotism. Lots of eligible men found this attractive, but she retreated for her own reasons in her own graceful way.

Monica Zimmerman lectures on this and other topics at the Academy of Fine Arts and recently talked at the Right Angle Club. We are grateful to her for pointing out the influence of John Singer Sargent in opening up for Beaux the borders of grand manner portraiture, enhancing the mood and intimacy by surrounding the subject with an environment, rather than the dark gloomy plain backgrounds that are so traditional. Parenthetically, there is a marvelous example of this school of portraiture hanging in the hall of presidential portraits at the Union League. Among the collection of gloomy dark backgrounds for the other presidents, the portrait of George Herbert Walker Bush shows him on the portico of the White House and allows his luminous likeableness to shine out among the severe and stately presidential peers. Photographic portraiture has to struggle to blot out distracting background; portrait photographers like Bachrach struggle to imitate what is more natural for backgrounds in painted portraits. Except for those of the school of Cecelia Beaux.

|

|

Beaux's two-year-old niece and favorite model, Ernesta Drinker (1892-1981) |

One other feature to be noticed about the Beaux exhibit is her outstanding ability to work with white. There are white gowns, white frilly dresses, white upholstery in a profusion seen rarely because it is so difficult to do.