5 Volumes

Philadelphia Medicine

Several hundred essays on the history and peculiarities of Medicine in Philadelphia, where most of it started.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Health: Philadelphia

New volume 2014-08-04 22:18:40 description

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

Philadelphia Physicians

Philadelphia dominated the medical profession so long that it's hard to distinguish between local traditions and national ones. The distinctive feature is that in Philadelphia you must be a real doctor before you become a mere specialist.

Nation's First Hospital, 1751-2016

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

As commonly stated in medical history circles, the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital is the history of American medicine. The beautiful old original building, with additions attached, still stands where it did in 1755, a great credit to Samuel Rhoads the builder and designer of it. The colonial building on Pine Street stopped housing 150 patients around 1980, supposedly at the demand of the Fire Marshall, although its perpetual fire insurance policy still owes the hospital several thousand dollars a year as an unspent premium dividend. There may have been one small fire during two centuries of use, but its true fire hazard would be difficult to assert. It was just out of date. The original patient areas consisted of long open wards, with forty or so beds lined up behind fluted columns, in four sections on two floors. The pharmacy was on the first floor, the lunatics in the basement, and the operating rooms on the third floor under a domed skylight. It was entirely serviceable in 1948 when I arrived as an intern doctor. Individual privacy was limited to what a curtain between the beds would provide, but on the other hand, it was possible for one nurse to stand at the end of the award and recognize any distress among forty patients immediately. In this trade-off between delicacy and utility, the utility was certain to be preferred by the Quaker founders. Visitors were essentially excluded, and if a patient recovered enough to be unnaturally curious about neighboring patients, well, he had probably recovered enough to go home.

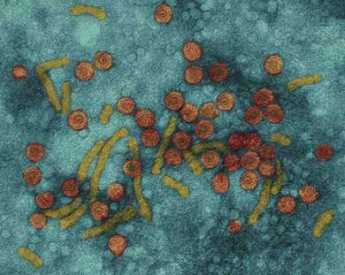

Located between two large rivers, South Philadelphia up to ten blocks away was essentially a swamp until the Civil War. So, there were seasonal epidemics of malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, and poliomyelitis at the hospital until the early twentieth century. Philadelphia was a port city, so sailors brought in cases of venereal disease, scurvy, even an occasional case of anthrax or leprosy. During the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, tuberculosis, rheumatic fever, and diphtheria were part of clinical practice. But underlying the ebb and flow of environmental effects, there was a steady population of illness which did not change a great deal from 1776 to 1948. These patients were all poor, because the rules in Benjamin Franklin's handwriting restricted service to the "sick poor, and only if there is room, for those who can pay." In 1948 there was a poor box for those who might feel grateful, but no credit manager or official payment office. The matter had been considered, but the cost of collection was considered greater than the likely revenue. When Mr. Daniel Gill was offered the position as the hospital's first credit manager, it was suggested that he be given a tenth of what he collected. To his lifelong regret, Dan Gill regretted that he refused an offer that he had felt he could not afford to accept.

So, the wards were filled with victims of the diseases of poverty, punctuated by occasional epidemics of whatever was prevalent. And a second constant feature of the patients was their medical condition forced them to be housed in bed. For centuries, physicians dreaded the news that a new patient was being admitted with "dead legs".

A Toast to Doctor Franklin

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

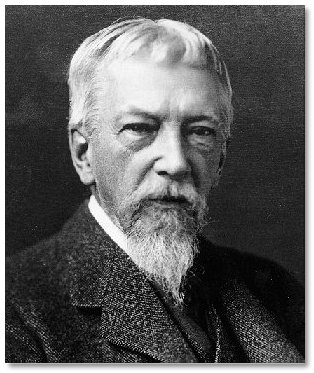

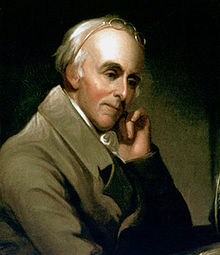

Benjamin Franklin's formal education ended with the second grade, but he must now be acknowledged as one of the most erudite men of his age. He liked to be called Doctor Franklin, although he had no medical training. He was given an honorary degree of Master of Arts by Harvard and Yale, and honorary doctorates by St.Andrew and Oxford. It is unfortunate that in our day, an honorary degree has degraded to something colleges give to wealthy alumni, or visiting politicians, or some celebrity who will fill the seats at an otherwise boring commencement ceremony. In Franklin's day, an honorary degree was awarded for significant achievements. It was far more prestigious than an earned degree, which merely signified adequate preparation for potential later achievement.

And then, there is another subtlety of academic jostling. Physicians generally want to be addressed as Doctor, as a way of emphasizing that theirs is the older of the two learned professions. A good many PhDs respond by rejecting the title, as a way of sniffing they have no need to be impostors. In England, moreover, surgeons deliberately renounce the title, for reasons they will have to explain themselves. Franklin turned this credential foolishness on its head. Having gone no further than the second grade, he invented bifocal glasses. He invented the rubber catheter. He founded the first hospital in the country, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and he donated the books for it to create the first medical library in the country. Until the Civil war, that particular library was the largest medical library in America. Franklin wrote extensively about gout, the causes of lead poisoning and the origins of the common cold. By inventing bar soap, it could be claimed he saved more lives from the infectious disease than antibiotics have. It would be hard to find anyone with either an M.D. degree or a Ph.D. degree, then or now, who displayed such impressive scientific medical credentials, without earning -- any credentials at all.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

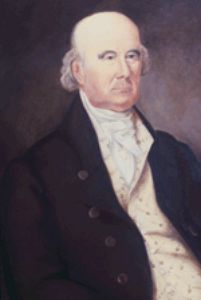

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

July 4, 1776: Patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on Independence Day

According to the records of the Pennsylvania Hospital, the following 48 persons were patients in the hospital on July 4, 1776:

| Richard Brinkinshire (Admitted 11/15/1775) | John Ridgeway (Admitted 12/26/1775) |

| James Chartier (Admitted 1/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/6/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) |

| Mary Yell (Admitted 2/7/1776l) | John Beckworth (Admitted 2/7/1776) |

| Bart. McCarty (Admitted 2/10/1776) | John King (Admitted 2/10/1776) |

| Robert Alden (Admitted 2/17/1776) | William Patterson (Admitted 3/6/1776) |

| Elizabeth Hanna (Admitted 3/9/1776) | John McMahon (Admitted 3/13/1776) |

| Mary Burgess (Admitted 3/23/1776) | Mary Anderson (Admitted 4/10/1776) |

| John Hatfield (Admitted 4/15/1776) | Eliza Haighn (Admitted 4/17/1776) |

| Charles Whitford (Admitted 4/24/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| Susanna Carrington (Admitted 5/8/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| William Johnson (Admitted 5/13/1776) | Lazarus Chesterfield (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| Mary Spieckel (Admitted 5/22/1776l) | William Edwards (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 5/23/1776, Lunatic) | Jane White (Admitted 5/25/1776) |

| Charles McGillop (Admitted 5/29/1776) | ---Fitzgerald (Admitted 6/1/1776) |

| Michael Rowe (Admitted 6/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 6/6/1776) |

| John Hughes (Admitted 6/12/1776) | Joseph Smith (Admitted 6/15/1776) |

| Esther Munro Lunda (Admitted 6/15/1776) | Mathew Coope (Admitted 6/19/1776) |

| Anne Patterson (Admitted 6/19/1776) | Thomas Savoury (Admitted 6/20/1776) |

| Rebecca Winter (Admitted 6/26/1776) | Elizabeth Manning (Admitted 6/26/1776) |

| Negro (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Elex. Scanvay (Admitted 6/24/1776) |

| Fanny Stewart (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Peter Barber (Admitted 6/29/1776) |

| Catherine Campbell (Admitted 6/29/1776) | Ann McGlauklin (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

| Elizabeth Lindsay (Admitted 7/3/1776) | Ann Jones (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

The records indicate the following diseases were the reason for admission of those patients. Although in Colonial times there was no medical delicacy to avoid offending readers, present privacy standards require that we strip the diagnoses from the name of the patient and list them independently. There is some overlap, sometimes making it difficult to judge which disorder caused the admission.

- Sore, poisoned or ulcerated legs: 16 cases

- Lunacy, mind or head disorders: 10 cases

- Syphilis: 7 cases

- Fever and Rheumatic fever: 7 cases

- Dropsy: 5 cases

- Gunshot: 4 cases

- Diabetes: 1

- Blindness with clear pupil: 1

- Spitting blood: 1 case

- Dislocated arm: 1 case

- Inflammation of face: 1 case

- Scurvy: 1 case

- broken arm: 1 case

The following physicians were elected at the Managers Meeting dated 5/13/1776:

- Dr. Thomas Bond

- Dr. Thomas Cadwalader

- Dr. John Redman

- Dr. William Shippen

- Dr. Adam Kuhn

- Dr. John Morgan

America's First Medical Interne, Jacob Ehrenzeller

This Indenture Witnesseth, That Jacob Ehrenzeller, son of Jacob Ehrenzeller of the City of Philadelphia hath put himself, and by these presents, with consent of his said father, doth voluntarily, and of his own free Will and Accord, put himself Apprentice to the Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital to learn the Art, Trade and Mystery, and after the Manner of an Apprentice to serve the said managers from the Day of the Date hereof, for and during, to the full End and Term of five years and three months next ensuing. During all of that Term, the said Apprentice his said Master faithfully shall serve, his Secrets keep, his lawful Commands every where readily obey. He shall do no Damage to his said Master, nor see it to be done by others, without letting or giving Notice thereof to his said Master. He shall not waste his said Master's Goods, nor lend them unlawfully to any. He shall not commit Fornication, nor contract Matrimony within the said Term.

He shall not play at Cards, Dice or any other unlawful Game, whereby his said Master may have Damage. With his own Goods, nor the Goods of others, without license from his said Master, he shall neither buy nor sell. He shall not absent himself Day nor Night from his said Master's Service without his leave: nor haunt Ale-houses, Taverns or Playhouses; but in all Things behave himself as a faithful Apprentice ought to do, during the said Term. And the said Master shall use the utmost of his Endeavor to teach or cause to be taught or instructed the said Apprentice in the Trade or Mystery of an Apothecary. And procure and provide for him sufficient Meat, Drink, washing Cloths and Lodging fitting for an Apprentice, during the said Term of five years and three months.

And for the true Performance of all and singular the Covenants and Agreements aforesaid, the said Parties bind themselves each unto the other, firmly by these Presents. IN WITNESS whereof, the said Parties have interchangeably set their Hands and Seals hereunto. Dated the first Day of June in the thirteenth year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George the third, King of Great-Britain, etc, Annoque Domini, One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy Three.

Signed and Delivered in the Presence of Jacob Ehrenzeller, Jacob Ehrenzeller Sr, Sam V. Coates

* * * *

|

| Jacob Ehrenzeller |

The Ex-residents Association of the Pennsylvania Hospital became active early in the Nineteenth century, and naturally concerned itself with just who was the first interne or resident of the hospital. It seemed probable that the first interne of the Pennsylvania Hospital would also be the first interne in America. When this indenture was discovered in the archives, Ehrenzeller became a likely candidate, although being apprenticed as an Apothecary did raise some questions. Nor did Ehrenzeller perform his indenture after the completion of medical school, as is now the custom; the first resident physician in that sense was Caspar Wister, in 1812. However, in colonial times most physicians did not go to medical school at all, qualifying as practitioners by working in the offices of practicing physicians, just as lawyers did for a much longer time. The argument is somewhat complicated by the existence of a medical school, the College of Philadelphia, created in 1765, and the fact that the upper crust of colonial medicine had gone to medical school in Edinburgh. That group of seven physicians with degrees gathered themselves together (in 1787) as the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which still exists as the nation's oldest medical organization.

Dorothy I. Lansing MD, then the clerk of the Section on History of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, interested herself in these issues, and privately published a pamphlet about it. The argument for regarding Ehrenzeller as an interned physician revolves around the fact that his father had gone to medical school in Europe, and was regarded as a physician even though he made his living by operating a tavern after he came to Philadelphia. Furthermore, the 16 year-old Ehrenzeller found his apprenticeship disrupted by the Revolutionary War, particularly the occupation of Philadelphia in 1777 by British troops who used the hospital for their wounded. Nevertheless, young Ehrenzeller served as a surgeon at the battle of Monmouth (June 28, 1778). Among the minute books of the Board of Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital was discovered a minute of June 26, 1773 with the terms that Jacob Ehrenzeller, Jr. "shall have leave at his own or his Father's expense to attend the lectures of the Medical Professors out of the Hospital during the last two years of his apprenticeship; to attend the Surgical Operations and Lectures in the Hospital free of any expense; and that the Apothecary for the time being shall duly instruct him in Physic and Surgery." Dr. Lansing concluded that this was "a unique concurrent internship: apothecary apprentice cum medical student arrangement that no doubt suffered innumerable changes due to wartime problems; Jacob Ehrenzeller was awarded a certificate of medical competency. The College of Philadelphia medical school having ceased to exist because of the war, he obtained no degree in medicine."

Dr. Lansing found even stronger evidence of his physician rather than apothecary status in the fact that immediately after the war he established a practice in Goshen, Chester County. While it was customary for practicing physicians of the time to support themselves as schoolteachers, storekeepers or bankers, Ehrenzeller was able to live exclusively on his income as a physician. Indeed, after his death in July 18, 1838, his estate was one of wealth. It seems unlikely that an apothecary masquerading as a physician would have flourished in those competitive times, and on this basis it is concluded that he came as close as the times permitted to the description of an interned hospital physician. The Ex-residents Society of the Pennsylvania Hospital was satisfied enough to declare Ehrenzeller to have been its first interne. And invites the rest of the nation's medical community to examine whether anyone else might have been better qualified to have that title earlier.

The Kappa Lambda Society of Hippocrates

Philosophical Hall

February 5th 1835, 3 1/2 PM

A special meeting of the Kappa Lambda was convened this afternoon by order of the President, Dr. Otto, at the request of Drs. Bache, Bond, and Wood for the purpose of settling and closing the concerns of the institution ....

Resolved that the Secretary be requested to transfer to the College of Physicians, for safe keeping, With the consent of that body, Journal of Proceedings and other manuscript documents of the Kappa Lambda Society to be deposited in the Archives of the College ....

Philosophical Hall

February l Sth 1835, 3 1/2 PM

.... Resolved that from and after the termination of this meeting the Kappa Lambda Society of Philadelphia be held to be dissolved.

Resolved that the foregoing minutes of the present meeting be now read, which being done, they are unanimously approved.

On Motion adjourned sine die.

Henry Bond, Secy,

WITH these resolutions, the Philadelphia branch of the Kappa Lambda Society of Hippocrates transferred its organizational records to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and then dissolved itself.

What was the Kappa Lambda Society of Hippocrates?

- An elitist clique dedicated to the advancement of its membership?

- A secret fraternal order?

- A scientific society that published one of America's most important medical journals?

- A society for the moral reform of medicine?

- A society for reviving the Hippocratic Oath?

- A society dedicated to the replacement of Hippocratic ethics with Thomas Percival's code of medical ethics?

- A medical society that served as the prototype for the American Medical Association?

- A failure from which the founders of the AMA learned how not to organize a national medical organization?

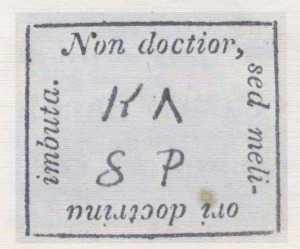

|

|

Seal of the Philadelphia chapter of the Kappa Lambda Society |

The answer that seems to emerge from the books, ledgers, and correspondence that the Philadelphia branch of Kappa Lambda transferred to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia 1835 is that the Philadelphia chapter was all of the above. Yet the only three scholars who have written about the society -- Chauncey Leake (1922), Lee Van Antwerp (l945), Philip van Ingen (1945) -- have tended to view it as only some of the above, casting Kappa Lambda as either "elf" or more commonly, as Van Antwerp marks, as an "ogre".

|

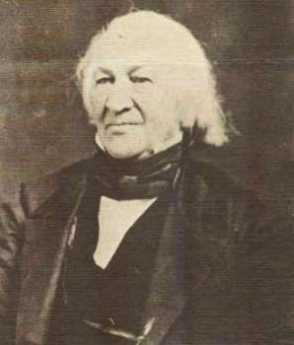

| Samuel Jackson, M.D. |

The Kappa Lambda Society began as a secret fraternal order whose members swore a version of the Hippocratic Oath, pledged to upload the honor of the medical profession, and promised to keep the existence of the society a secret. The earliest known records of the society are from Lexington, Kentucky, and date from 1820. But, as Van Ingen has suggested, the history of society is considerably older. What appears to have happened in Lexington was that, in 1820, Dr. Samuel Brown (1769-1830), as professor of medicine, became head of the local chapter of Kappa Lambda. Under his leadership, this chapter committed itself to the moral reform of American medicine and took as its objective the idea of having American doctors pledge themselves to adhere to the code of conduct that Dr. Thomas Percival (1740-1804) had published in 1803 under the title Medical Ethics. To implement these reforms the Lexington chapter of the Kappa Lambda Society of Hippocrates published the first American edition of Percival's code of ethics, Extracts from Medical Ethics or A Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conducts of Physicians & Surgeons in Private or General Practice (1821),and sought to establish new chapters of Kappa Lambda, whose members would pledge to adhere to the standards of conduct delineated in Percival's code.

When Dr. Brown went forth to spread the new Perivalean gospel, he found willing adherents in Philadelphia, where Samuel Jackson and seven other physicians (Franklin Bache, J.H.Gordon, Thomas Harris, Thomas T. Hewson, Hugh L. Hodge, Charlie D. Meigs, and Rene' La Roche)agreed to found a chapter. The Philadelphia constitution required all members to adhere to Percival's code of medical ethics and designated several members as "Guardians" with "the duty of preserving concord among all the members of the society, by arbitrating in all disputes referred to them, and prescribing the kind of reparation to be made .... (and) report(ing) ... whatever they may deem derogatory to its dignity and usefulness, in the misconduct of its members." The Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda was thus to be a self-policing medical community that would abide by laws (stated in Percival's Medical Ethics) and that had guardians to police and enforce these laws.

Philadelphia may have been the only chapter of Kappa Lambda to take Dr. Brown's commitment to a self-policing moral community seriously. His ideas had been awkwardly juxtaposed on top of the original conception of Kappa Lambda as a secret fraternal order. The Philadelphia struggled with this fundamental tension in drafting their constitution. At the core of the old fraternal order was a secret oath passed down from society to society. Philadelphians were initiated into the society with the following oath:

You (swear/affirm) that you will endeavor to exalt the character of the Medical Profession by a life of virtue and honor--that you will keep the secrets, guard the reputations and advance the interest of the Society and of each of its members; and that you will never encourage anyone to devote himself to the Study of Medicine whose leaning, talents, and honorable qualities are not such as to render him respectable in his Profession, and worthy to be distinguished as a member of this society.

Whatever the original intent of this oath, its fraternal aspects--"advanc[ing] the interests ... of each of (the) members" and excluded from the profession, or at least from its higher ranks, anyone insufficiently virtuous, honorable, learned, or talented to be elected to Kappa Lambda--seem more prominent than its moral commitments.

Each chapter, moreover, was free to develop its own initiation ceremony. The Philadelphians used the ceremony to put a reformist spin on the oath. The following words were to be pronounced by Philadelphia initiates immediately after they read the oath:

The venerable Hippocrates of Cos may be considered as the remote founder of this society and the considered as the remote founder of this Society and the {oath/affirmation} which you have taken is in substance the same as that administered to its members. The influence of this society on the morals and professional demeanor of the physicians of that period is attested to by the most respectable authorities.

Believing that the state of the Profession in this country so imperiously calls for reformation & knowing that we have not that rank and influence in the community, to which as members of a liberal profession we are entitled, we have determined under a solemn sense of duty to associate on just principles for the purpose of elevating the character of our Vocation.

In other words, the oath was simply a ritual reminder of a historical reform movement. One could no longer reform medicine by excluding the unworthy, however, because "unworthy brethren" had already been admitted to the profession and had “humbled†the profession through their “sinister conduct.†The Problem facing the new Hippocrates, the Kappa Lambda, was reforming an already corrupt profession that problem could only b resolved by teaching the profession t associate on "just principles"(i.e., Percival's principles of Medical Ethics).

The need for "just" and benevolent principles of association is restated in the Preamble to the Philadelphia chapter's constitution, to which very member affixed their signature upon joining the organization.

As the bonds of all associations and confederacies by which their parts are firmly and permanently linked together, must be the eternal principles of benevolence and justice-we the undersigned-professing to follow implicitly, desirous of rigidly applying, these principles to our particular situation; uninfluenced by motive of personal ambition, disclaiming any right or wish to infringe on social compact, assume any power, delegate any authority which is incompatible with the religion we profess, the laws of our country or the fair and honourable advancement of our fellow citizen:--do hereby unite and pledge ourselves to be governed by the following constitution, and the laws which may afterwards be framed under it. Nor can we ever be unmindful, that our present efforts, directed to the support of the dignity, and extension of the usefulness of the medical profession, will more readily meet with their successful fulfillment in the encouragement of virtue and science, the pure lights of which must eventually dispel the mists of immorality and ignorance. To this end, we are to engraft medical ethics on moral precept, and sedulously cherish that friendly feeling and courteous conduct, in our professional and social intercourse, which can alone confer happiness on individuals, and promote the welfare of mankind.

With the words "uninfluenced by personal ambition ... [and] disclaiming any right or wish to infringe on ... the fair and honourable advancement of our fellow citizens" the Philadelphia chapter explicitly annulled the self-serving clauses of the traditional Kappa Lambda oath; indeed, by "engraft[ing Percival's] medical ethics on [Hippocratic] moral precept," they had effectively consigned the oath to a purely ceremonial function. The Philadelphia was thus continuing along the path taken by Samuel Brown (who beamed upon the Philadelphia branch and lauded its work), converting a vaguely Hippocratic elitist fraternal order into a society seriously committed to reforming American medicine.

The Philadelphia broke entirely new ground on another issue. Citizens of a city that was the center of the American science, the Philadelphia quite naturally wedded the two distinct ideas of scientific and moral reform into a single progressive union: pledging themselves to "the encouragement" of both "virtue and science" and to dispelling "the mists" of both "immorality and ignorance." Article V of the Philadelphia chapter's constitution made it morally obligatory for "Every member ... to contribute any practical fact, discovery, or view, which, in his opinion, will tend to the improvement of the profession, and the amelioration of the condition of the sick and infirm."

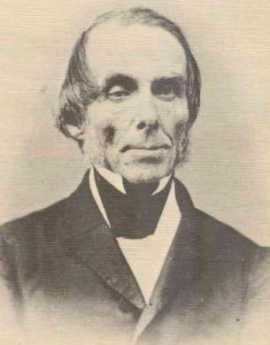

|

| John Bell, M.D. |

Such statements must have been intuitively obvious to the founding members of the Philadelphia chapter. When Samuel Jackson(l787-1872), who is generally credited with writing the constitution, formed the chapter in 1822, he was already professor of material medical at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and a member of the American Philosophical Society; by the time the constitution was formally enacted in 1825, he had become professor of the institutes of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. A year later Franklin Bache (1792-1864) became a professor of chemistry at the Franklin Institute. Similar career patterns are evident in most of the other founding members; Hugh L. Hodge(l836-1881) was a lecturer on the principles of Surgery at the Medical Institute of Philadelphia, and went on to become a professor of obstetrics at the University of Pennsylvania; Charles D. Meigs (1792-1869 had been a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, became a member of the American Philosophical Society, and went on to become a professor of obstetrics at the Jefferson Medical College; Rene' la Roche(1795-1872) was a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences and, shortly after the constitution was approved, became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

The Philadelphia' fervor to reform medicine and to advance medical science clashed with the secret fraternal inclinations of traditional Kappa Lambda chapters. First, there was the issue of Percival's Medical Ethics. In 1823, following the precedent set by Dr. Brown, the Philadelphians published 500 copies of a newly revised editions of Percival' code, sending them to older chapters in Baltimore, Lexington, and New York, and distributing three copies to each member of the Philadelphia chapter(who appear to have used the extra copies to recruit new members). A new member, John Bell (1796-1872), was instructed to publish a copy of the Philadelphia edition of Extracts from the Medical Ethics of Percival in the National Gazette. He would later chair a subcommittee that revised and published yet another edition of the Extracts in 1826. As a member of a society committed to abiding by Percival's code, dedicated to disseminating its ideals, and seeking to recruit like-minded physicians, the Philadelphians thought it was perfectly natural to continuously revise and publish new editions of Percival. Yet publication was a disturbingly public activity for a supposedly secret society like Kappa Lambda.

Even more disturbing to the already established non-reform chapters of Kappa Lambda was the Philadelphia chapter's attempt to encourage scientific research by American physicians through The North American Medical and Surgical Journal. A regularly published journal was an event more public enterprise than the sporadic publication of revised editions of Percival's code. The New York chapter was instantly hostile to the idea, demanding that the existence of the Kappa Lambda society be kept secret. The District of Columbia chapter was concerned with the question of secrecy and wrote to the Philadelphia chapter to "ascertain particularly" whether in light of the "Journal which is to be proposed ... you intend to make public the existence of the KL societies generally." The journal's editors (Drs. Hodge, Bache, Meigs, Benjamin Homer Coates, and LaRoche) did not initially acknowledge the relationship between the journal and society. In February 1827, however, Dr. Meigs proposed that the Philadelphia chapter rescind its pledge of secrecy. The proposition was formally accepted by the membership in June. In meantime, the editors of The North American Medical and Surgical Journal announced that the Journal was supported by the Kappa Lambda Society.

Removing the Philadelphia Chapter from behind the shroud of secrecy was problematic. The older fraternal societies had never accepted Dr. Brown's reformist agenda and resisted it at every tum. A move vexatious challenge to publicity was the central reformist tenet of voluntary self-policing. It was one thing for members to volunteer to submit their personal and professional conduct to the private scrutiny and possible censure of their peers within the confidential confines of a secret society, it was quite another to voluntarily expose themselves to possible public censure. It took over two years to settle this question, when, in 1830, it was decided that all meetings would be opened to the public--except those involving inquiries into the conduct of the membership. This compromise in place, it was officially decided in June 1830 to announce the existence of the Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda. By this time, however, the tide of public opinion had begun to tum against Kappa Lambda; all chapters were swamped in the backwash of a scandal over the conduct of the older non-reform New York chapter.

An anonymous letter to the Medical Society of the State of New York had revealed not only the existence of a "Secret Medical Association" operating in city , but the content of its secret oath, and the names of all its members--which included all the attending physicians and surgeons at the New York City Dispensary, the New York Hospital( except for one, ) and the Lying-in Hospital (except for two). The simple fact that a preponderance of members in the upper echelons of New York were members of a secret society prompted suspicions of favoritism. The Medical Society convened a Special Committee to Investigate a Secret Medical Association. The secret oath of the New York chapter of Kappa Lambda (a pre-reform chapter, founded around 1819) confirmed the Special Committee's worst suspicions.

I-do solemnly promise, that by all proper means, J will promote the professional respectability and welfare of the members of this association and vindicate their characters when unjustly assailed, and that J will not demand any pecuniary acknowledgment for such instruction as it may be convenient for me to afford to the son of an indigent member, as may be in the opinion of the society qualified by his previous educations, and talents, and moral character, to become a respectable and useful member of the profession, but I will afford such instruction gratuitously, in conjunction with the members of the society.

This oath, the Special Committee observed, acknowledge that the members of the society were pledged "to promote the professional respectability and welfare ... of each other." Moreover, when the Special Committee asked the members of the New York chapter what they had done as an Association for the cause of science and the honor of the profession, the New Yorkers could not cite any significant achievements. Consequently, on the evidence of the oath and the pattern of appointments at New York hospitals, the Special Committee concluded that members of Kappa Lambda had in fact created "an unjust monopoly of the emoluments and honors of the profession.: They had evoked the name "Hippocrates" simply to put a patina of honor and a veneer of venerability on the shameless pursuit of personal advantage. The Special Committee reprimanded all members of "the Secret Association" and advised any man of character to resign.

|

| Title Page of Volume I |

Prior to June 1830 the Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda had been doing quite well. Beginning with a small group of eight initiates, it had rapidly enrolled many prominent physicians, ultimately initiating ninety-eight members--with seventy dues-paying members residing in Philadelphia. The North American Medical and Surgical Journal was generally regarded as one of America's leading medical periodicals. Meetings were well attended; some drew crowds of over forty members. Yet, after word of the Special Committee report reached Philadelphia, attendance fell below the minimal quorum required by Kappa Lambda's Constitution. The Only meeting that had a quorum large enough to conduct business was that of 5 February 1835, when ten members assembled to dissolve the chapter. Samuel Jackson resigned on the first word of the scandal, but many members simply ceased to pay their dues. Without the membership dues to sustain it, The North American Medical and Surgical Journal was discontinued.

It mattered little that no one had ever accused the members of the Philadelphia chapter of monopolizing emoluments and honors; it mattered even less than the Philadelphia chapter's constitution forbade favoritism concerning any member, or that it had tried to become a public society, or even that, in striking contrast to the New York chapter, it had made contributions to medical science by publishing a major medical journal and Percival's Medical Ethics. The Philadelphia chapter was still a society, and the Special Committee had argued that secrecy corrupted any society, no matter how noble its initial intent. The stigma attached to Kappa Lambda was so deep that as late as 1858, when the New York chapter of Kappa Lambda sent an openly-declared member as its representative to a national meeting of the AMA, his credentials were rejected.

The Story of Kappa is more than a quaint tale, for as Chauncey Leake has correctly observed: "the same forces[that] were at work in establishing the American Medical Association in 1847, and in passing its elaborate code of ethics." The Philadelphia "forces" exerted their influence at the end of a national medical convention that had been convened in New York in 1846 to set national standards for medical education. After two days of discussions, the conferees were unable to reach any consensus. The Meeting was about to dissolve in failure when hoping to salvage something from the failed convention, Isaac Hayes(l796-1879), former secretary of the Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda, proposed that the convention reconvenes in Philadelphia the next year to create a national medical society dedicated to reforming American medicine--ethically as well as educationally. The convention delegates endorsed Dr. Hays' proposal and put him in charge of making arrangements for the 1847 Philadelphia convention. They also established a committee to draft national code of medical ethics. Chairing this committee was John Bell, who had chaired the 1826 Kappa Lambda Committee to revise Percival's Medical Ethics; Dr. Hays, who had been secretary and editor for the 1826 Kappa Lambda committee, played the same role for the 1846 code-drafting committee, The third Philadelphian on this committee, Governor Emerson (1796-1874), was also an alumnus of the Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda.

The American Medical Association and its code of ethics were, as Leake suggests, an extension of the ideas and ideas that originated in the Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda. Yet the failure of Kappa Lambda had taught the Philadelphians some important lessons. Kappa Lambda had been secret, fraternal, and exclusive; by contrast, the AMA was to be public, political, and inclusive--a grand public alliance of all the forces of reform and of all the hospitals, medical schools, and medical societies in America. Kappa Lambda had been founded on a gentlemanly version of the Hippocratic Oath. Chastened by their experience with corrupt versions of the Oath, the former Kappa Lambda eschewed any mention of Hippocrates of his oath in AMA Code of Ethics. The new AMA Code of Ethics, like the old Kappa Lambda code, was based on Percival ethics that called 0 physicians "to obey the calls of the sick," to treat every patient skillfully, attentively, faithfully, tenderly, but firmly while tempering medical authority with a spirit of equality. Moreover, "every case committed to the charge of a physician" would "be treated with attention, steadiness, and humanity"; every patient would be entitled to confidentially, delicacy and discretion. Yet the new AMA code of ethics required even more of physicians that the older Percival codes: having once been crucified on charges on selfishness and monopolization, the former Kappa Lambdans obligated physicians to self-sacrifice on behalf of their patients and the public. They required physicians to recognize "poverty ... as presenting valid claims for gratuitous services," and to pledge that "when pestilence prevails" it is their "duty to face the danger, and to continue their labors for the alleviation of suffering, even at the jeopardy of their own lives. "

The grand moral vision of the former Kappa Lambda energized the American Medical Association and made it the preeminent moral and political voice of American medicine. In the twentieth century, as the Kappa Lambda's reformist vision lost its vigor, the tale of Kappa Lambda became the stuff of scholarly debate=most scholars have tended to dismiss it as an idiosyncratic and ultimately unimportant chapter in the history of American medicine. Yet it seemed to me, as I surveyed the records that the Kappa Lambdans had turned over to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, that 1997 was an appropriate time to reassess its legacy. For in wrestling with the task of developing formal standards of medical ethics that could serve as the basic of professional self-policing, in obligating American physicians to serve the interests of the public as well as their willingness to put the care of their patients ahead of their own financial interests and physical safety, the Kappa Lambda had formulated very high ideals for American medicine. Looking back on these ideals on the sesquicentennial of the founding of the American Medical Association and its Code of Ethics one is still struck by the grandeur of their moral vision--and also by the thought that the prominent role ethics still plays in American medicine is ultimately the heritage of the Philadelphia chapter of Kappa Lambda.

Robert Baker, Ph.D.

Union College, New York

Lumpers In Constant Combat With Splitters

|

| James Boswell's Book |

Some colleges produce managers by teaching management theory, but in certain Ivy League colleges it is thought to be more useful to teach how to dominate a committee, eventually perhaps a board of directors, or a board of trustees. The handbook of instruction is James Boswell's Life of Johnson which is a rather large book of verbatim notes that Boswell took of his many lunches at a London club in the 18th Century. Boswell was a quiet mouse privileged to sit in the company of the great Dr. Samuel Johnson, surrounded by the most eminent intellects of the Enlightenment. Boswell carefully manages the background of each episode, describing the issue and the various arguments, and then -- Sam Johnson's booming voice settles the matter. After he speaks, the meeting is over.

|

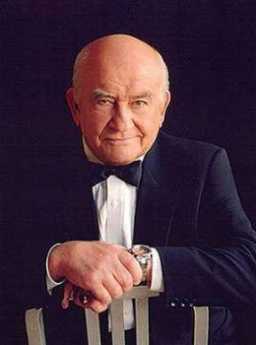

| Dr. Samuel Johnson |

"Why, sir", says Johnson, and then look out for the one-liner to follow. We get the impression that Dr. Johnson used that "Sir" signal to indicate he had enough of these dumb arguments, and soon would come the growled epigram that scatters any token resistance. Boswell may have neglected to record instances where the great Johnson was defeated in debate, who knows. We are left with the distinct impression that if you engaged in lunch table conversation with Sam, you were almost certain to lose. So that's what Ivy League students are being taught: how to win a debate at a committee meeting, in the expectation they would spend much of their lives in committees, boards, and even cabinets. That's how the English-speaking world gets its work done and its decisions made. That's what lunches at the Franklin Inn Club, or the club tables of the Union League, are trying to do for the education of neophytes.

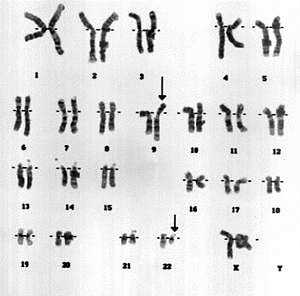

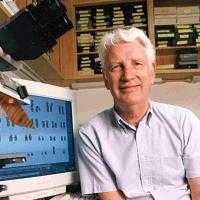

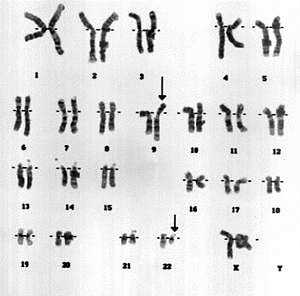

As the goggle-eyed student of the great Chauncey Tinker, who gave young Pottle his start in life, it was an awesome performance for me to watch. But the rules of this game never became entirely clear to me, I'm afraid, until the other evening when I listened to Peter Nowell describe in a half-dozen brief paragraphs how he had revolutionized prevailing theories of the cause of cancer. The Franklin Institute then followed the award ceremony by putting on an all-day symposium of notables who run elaborate enterprises in cancer research, essentially funded by the National Institutes of Health, your tax dollars at work again. Last year, the NIH dispensed thirty billion -- you heard me -- dollars in research grants to internationally known research entrepreneurs, and if you can stay awake during their talks, there must be something the matter with you. So far as I could see, they were painstakingly describing every grain of sand on the beach, whereas Peter Nowell made the whole beach electric and clear in ten minutes. Essentially, he was saying that each patient's cancer is caused by a long chain of events, starting with a single mutation within a single cell. All the other cancer cells of a patient are descendants of that first one, which triggered the cascade of chemical events now repeated by the descendants. To stop the process, you probably only have to find a way to break the chain at one vulnerable point. Then you have a cure, without necessarily understanding every other link in the chain.

Peter Nowell described himself as a "lumper", admitting that most scientists are "splitters". A splitter quite reasonably attacks a complex problem by isolating one small piece of it at a time; that's really a pretty good way to address overwhelming complexity when you encounter it. But you can be sure that people of that mindset should not be found in a President's cabinet, deciding how to save the world from impending disaster. Whether by their own genetic predisposition or as a result of peer pressure in their profession, they are habitual splitters. And it suddenly occurred to me why Sam Johnson's one-liners always won the argument; he was a lumper. Usually right, sometimes wrong, never in doubt. Witty as a Frenchman, but as quick as a rattlesnake. Cordial, perhaps, unless you disagreed with him.

We need more lumpers. If they get that way from the likes of Chauncey Tinker, we need to print more copies of The Life of Johnson. If they are born that way, maybe we need a breeding farm for lumpers, which is what the Assembly Ball amounts to. But don't get me wrong, we need more splitters, too. They just have to learn their place at the table.

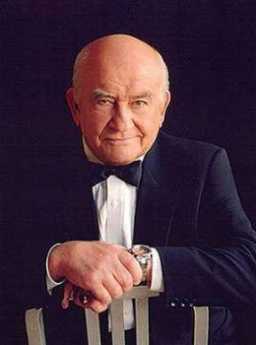

A Toast To Silas Weir Mitchell, MD

|

| Silas Weir Mitchell |

Silas Weir Mitchell lived to be an old man during the Nineteenth Century when it was unusual to get very old. He was an important part of both the Philadelphia medical scene and the literary one. He became known as the Father of American Neurology as a published studies of nerve injuries caused by the Civil War. He published about 150 scientific papers, including famous investigations of the neurological effects of rattlesnake venom. His most famous medical treatment was the "rest cure" for hysteria, while his most enduring scientific discovery was the phenomenon of causalgia. He despised Freud, and psychonanalysis. No doubt the feeling was mutual, but the passage of time has tended to favor Mitchell more than Freud. The central role of sex is the essence of Freud's viewpoint, while Mitchell is summarized in the remark that, "those who do not know sick women, do not know women."Struggling medical students can take heart from the well-documented fact that Mitchell applied to the Pennsylvania Hospital for an internship, and was rejected. Upset by the experience, he toured Europe for a year and applied again. He was again rejected. He later applied for the faculty at Jefferson and was rejected, but his reaction to that was one of rage and vengeance. Just what these two episodes out of Philadelphia medical politics really mean, remains to be clarified by Mitchell's biographers.

|

| Franklin Inn |

Mitchell's second career was literary, publishing 12 novels and 5 books of poetry. He is honored as the founder of the Franklin Inn Club, for century home to every important literary figure in Philadelphia. It is striking that he selected Benjamin Franklin as the guiding star of the Inn since Franklin similarly was eminent in both science and culture, and an ornament to conversation and society. In a pacifist Quaker City, both men approved of combat, and his novel about Hugh Wynne stresses that his hero was a "Free Quaker, meaning one who fought in the Revolution. Because of his strong Republican views, he was never made a professor at the local medical school.

|

| College of Physicians |

Mitchell's patient Andrew Carnegie donated the funds to build a new building for the College of Physicians when Mitchell was its President. When Mitchell was president of the Franklin Inn, Carnegie wrote him, asking for suggestions about donating a small sum, say five or ten million, and asking where it should go. That was the Inn's big chance, all right, but somehow it failed the test. Mitchell suggested that the money be given to raise the salaries of college professors, thus perhaps suggesting that this veteran of many academic revolts did eventually soften his views.

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

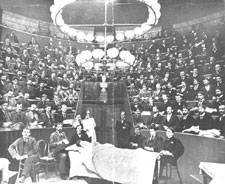

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Link to:Medical Club of Philadelphia

This concludes the general topic Medicine in Philadelphia. The more specific topic area of the Medical Club of Philadelphia (founded 1892 and still operating) can be reached by clicking on the title below. It's large, so wait a moment for it to come up:

» Click here for THE MEDICAL CLUB OF PHILADELPHIA «

Medical Club of Philadelphia, Appendix B, Membership

The Club grew robustly to the point where it attained a total of 1.393 members 1924 (In 1911 it had a thousand members compared to a total of forty thousand in the American Medical Association.) Exact figures are not available for all years. Some totals were taken from Annual Reports, but these figures are distorted by the fact that for many decades they continued to count persons who were two years delinquent in dues, as members. In some cases, they also counted applicants who had not paid any dues or admission fees. It was not until the 1970s that dues were collected before applicants were elected to membership.

For some years numbers were computed from records of dues & initiation fees paid. In other cases, where members were elected late in the year, their dues were credited both to the year paid and following year. Financial records are not available for some years, and in others, there simply are no records from which figures can be computed.

1893 570

1899 230

1900 313

1901 365

1902 460

1903 570

1904 644

1905 614

1906 640

1907 799

1908 846

1909 928

1910 931

1911 998

1912 1,010

1913 999

1914 1,042

1915

1916 1,107

1917 1,121

1918 1,067

1919 1,190

1920 1,211

1921 1,235

1922 1,205

1923

1924 1,393

1925 1,362

1926 1,359

1927 1,258

1928 1,329

1929 1,288

1930 1,348

1931 1,247

1932 1,159

1933 1,079

1934 982

1935 936

1936 910

1937 868

1938 821

1939 854

1940 860

1941 870

1942 767

1943 749

1944 748

1945 752

1946 765

1947 792

1948 990

1949 1,007

1950 965 (Dues increased

1951 942 from $5 to $10)

1952 958

1953 936

1954 924

1955 880

1956 876

1957 857

1958 800

1959 802

1960 799

1961 756

1962 724

1963 728

1964 703

1965 696

1966 684

1967 679

1968 671

1969 674

1970 654

1971 619

1972 629

1973 590

1974

1975 669

1976 555

1977 446 (Dues increased

1978 410 to $25)

1979 410

1980 412

1981 379

1982 387

1983 398

1984 329 (Dues increased

1985 409 to $35)

1986 390

1897 397

1988 387

1989 400

1990 398

1991 388

Appendix D, Presidents of the Club

Presidents of the Medical Club

*1892-4 John H.W. Chestnut, M.D.

*1895-6 Hobart A. Hare,M.D.

*1897-8 John H. Musser,M.D.

*1899-0 James M. Anders,M.D.

*1901-2 Edward L.Duer, M.D.

*1903-4 Edward E. Montgomery, M.D.

*1905-6 Roland G. Curtin, M.D.

*1907 L.Webster Fox, M.D.

*1908 George McClellan, M.D.

*1909 Wharton Sinker, M.D.

*1910 James B. Walker, M.D.

*1911 William L. Rodman, M.D.

*1912 S. Lewis Ziegler, M.D.

*1913 James C. Wilson, M.D.

*1914 Samuel D. Risley, M.D.

*1915 McCluney Radcliffe, M.D.

*1916 Judson Daland, M.D.

*1917 Charles K.Mills, M.D.

*1918 Albert P. Brubaker, M.D.

*1919 G. Oram Ring, M.D.

*1920 Francis X. Dercum, M.D.

*1921 Barton C. Hurst, M.D.

*1922 Ernest Laplace, M.D.

*1923 John B. Clark, M.D.

*1924 William D. Robinson, M.D.

*1925 Charles W. Burr, M.D.

*1926 Wilmer Krusen, M.D.

*1927 J. Torrance Rugh, M.D.

*1928 Orlando H. Petty, M.D.

*1929 J. Norman Henry, M.D.

*1930 John M. Fisher, M.D.

*1931 Frank C. Hammond, M.D.

*1932 Isador P. Strittmatter, M.D.

*1933 George M. Piersol, M.D.

*1934 Charles A. E. Codman, M.D.

*1935 Edward J. Klopp, M.D.

*1936 Paul J. Pontius, M.D.

*1937 Frederick S. Baldi, M.D.

*1938 John D. Mclean, M.D.

*1939 Henry B. Kobler, M.D.

*1940 Milton F. Percival, M.D.

*1941 W.Burrill Odenatt, M.D.

*1942 Walt P. Conaway, M.D.

*1943 Wayne P. Killian, M.D.

*1944 William Bates, M.D.

*1945 Bernard P. Widmann, M.D.

*1946 J. Allan Bertolet, M.D.

*1947 Edgar S. Buyers, M.D.

*1948 Joseph W. Post, M.D.

*1949 Eugene P. Pendergrass, M.D.

*1950 Joseph C. Birdsall, M.D.

*1951 Francis F. Borzall, M.D.

*1952 Myer Solis-Cohen, M.D.

*1953 Sameul G. Shepherd, M.D.

*1954 Theodore R. Fetter, M.D.

*1955 Francis G. Harrison, Sr., M.D.

*1956 George E. Pfahler, M.D.

*1957 Edward A. Bortz, M.D.

*1958 William A. Lell, M.D.

*1959 George E. Cormeny, M.D.

*1960 J. Rudolph Jaeger, M.D.

*1961 Jacob H. Vastine, M.D.

*1962 Joseph M. Kuder, M.D.

*1963 Henry S. Bourland, M.D.

*1964 Francis G. Harrison, Jr., M.D.

1965 Thomas M. Birdsall, M.D.

1966 George P. Keefer, M.D.

1967 Frederick Murtagh, M.D.

1968 Robert E. Booth, M.D.

*1969 Frederic H. Leavitt, M.D.

*1970 Paul J. Poinsard, M.D.

*1971 Elmer L. Grimes, M.D.

1972 Edmond Preston,III, M.D.

*1973 N. Henry Moss, M.D.

1974 Richard C. Putnam, M.D

1975 Federick P. Sutliff, M.D.

1976 H. Keith Fischer,M.D.

1977 H. Craig Bell, M.D.

1978 Thomas B. Mervine, M.D.

1979 F. Peter Kohler, M.D.

1980 Goerge E. Ehrlich, M.D.

1981 Robert D. Harwick, M.D.

*1982 Stewart McCracken, M.D.

1983 Joseph A. Wagner, M.D.

1984 Edward J. Resnick, M.D.

1985 Eugene B. Rex, M.D.

1986 John A. Koltes, M.D.

1987 James C. Hutchison, M.D.

1988 Timothy J. Michals, M.D.

1989 Joseph W. Sokolowski, M.D.

1990 Herminio Muniz, M.D.

1991 F. Douglas Raymond, Jr., M.D.

1992 Raymond Q. Seyler, M.D.

A Toast To J. William White, MD

JWilliam White left a legacy to the Franklin Inn, the income from which was to pay for an annual dinner, with all the trimmings. Good as its word, the Inn holds the J. William White dinner every year on Benjamin Franklin's birthday, although inflation and fluctuations of the stock market require it to make a modest charge for attendance. White also created the J. William White Professorship in Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, a chair which was once occupied by Jonathan Rhoads.

|

| William J White MD |

These trust-fund memorials do little to convey the wild and glamorous image of Bill White. White was a member of the First City Troop and fought the last known honest-to-goodness duel on Philadelphia's field of honor (in the accidental "wedge" of disputed land between Delaware and Pennsylvania). The right and wrong of the argument about wearing the City Troop uniform are in dispute, but the details boiled down to White at the critical moment raising his gun to the sky and firing at the stars. That it was not a meaningless gesture was then brought out by his opponent ( a fellow Trooper named Adams) taking slow and deadly aim -- but missing him.

White was an academic in the sense that he was the first, unpaid, Professor of Physical Culture at the University of Pennsylvania. Active in the Mask and Wig Club, he was a chief surgeon at Philadelphia General Hospital, chief surgeon to the Philadelphia Police, and chief surgeon to the Pennsylvania Rail Road. He is the surgeon actually operating in Thomas Eakins' Agnew Clinic, while Agnew himself stands as the "rainmaker", to use a term from legal circles. He was Chairman of the Fairmount Park Commission, and numerous other positions where political contact was more important than surgical skill. When World War I came along, he was off to France with the University of Pennsylvania Hospital Unit, writing two books with Theodore Roosevelt. Although his friendship with Henry James suggests greater literary talent, he was supportive of Adams' transfer of citizenship in protest of America's staying out of World War I; but nonetheless, Roosevelt published more than thirty books. What emerges from the history of Bill White is flamboyance and lots and lots of unfettered energy. He might feel a little out of place at one of his endowed dinners today, but he was probably always a little out of place in any company -- and didn't care a whit.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890 | Amazon |

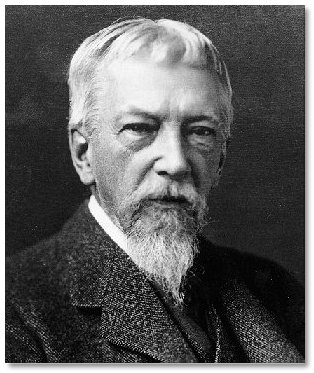

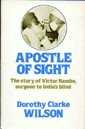

Victor Rambo, Indian Eye Surgeon

|

| Apostle of Sight |

There have been at least twelve documented generations of the Rambo family in Philadelphia. Historical justification can be found for the idea that this was the first family to settle within what are now the city limits. Victor Clough Rambo MD was an unpaid intern at the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1927; you will find his nameplate on the wall.

Victor early made up his mind that he was going to go where he could do the most good. Considerable thought led him to learn how to extract cataracts, and go to India to extract as many as he could. from time to time, he would return to America to visit family, and to give some speeches to raise money for his project.

The builders of our enormously costly hospital castles might give some thought to the fact that Victor did most of his surgery in tents. His system was to send out teams to the next two villages, whenever he was, with the news, "Bring in your blind people, the eye doctor is coming." When he then arrived, he set about operating on cataracts from dawn to dusk, in a country where the supply of cataracts was essentially unlimited. There was no time to operate on the comparatively minor visual disturbances so commonly treated in America today; he had to concentrate on people who were really blind, and in both eyes.

He wrote a book about his experiences, and perhaps there you could find data to calculate the number of people who were restored to a useful existence by his efforts. Surely, it was thousands. He just kept going at it, and when he died he was a very old man.

Emperor's Doctor

|

| Kitamura |

As told by one of his fellow interns who is now a very old man, Kitamura was one of the best interns the Pennsylvania Hospital ever had; diligent, dependable, intelligent and infinitely polite. He married one of the hospital's nurses, and they tended to keep to themselves, especially in 1941, as war clouds began to gather. About two months before Pearl Harbor, both of them mysteriously disappeared. Kimura's wife later wrote one of her friends that they were in Japan. After the war, it was learned that she had been placed in a concentration camp as an enemy alien, and when released, had divorced him.

Still later, it was learned that Kimura had a distinguished medical career in Japan. He kept up a minimal sort of correspondence with his old intern pals, inviting them to visit if they were ever in Japan.

In 1985 one of them did so, going to the largest hospital in Tokyo to inquire. Great silence ensued; unfortunately, the revered and distinguished physician had recently died. You knew, of course, that he was the Emperor's personal physician.

Discipline for the Disciple

|

I.S.Ravdin was President Eisenhower's surgeon; Chick Koop was President Reagan's Surgeon General. Both of them were overshadowed by Jonathan Rhoads. Even in a physical sense, this was true. Rhoads was a foot taller than almost anyone. Big bones, too.

During the Second World War, Ravdin led almost every doctor in the University of Pennsylvania off to some military hospital unit or other, and in fact, the 900-bed hospital in Philadelphia was left with only two surgeons, Koop and Rhoads, ineligible for military service because of previous tuberculosis. Koop was a first-year resident in training, so for practical purposes, Rhoads was the only surgeon. Even after eliminating purely elective or optional surgery, the workload was staggering, and the number of operations was prodigious.

Rhoads devised a system. The young trainee, Koop, would do the time-consuming work of opening the belly wall and Rhoads would then do the internal surgery, following which Koop would close the wound while Rhoads was operating on another patient. As Koop told the story at Rhoads' 90th birthday celebration, one day a patient was to have his gall bladder removed. Rhoads told him to open the wound, first, the skin, then the fascial layer, then the peritoneum, while he was finishing up with another patient in another room. At that point, Rhoads felt he would be able to come in and remove the gall bladder. Most gall blabbers are firmly attached to the nearby liver, and must be shaved loose before it is possible to put a clamp around the base to remove them.

On this day, two things were different. Rhoads was delayed in the other room because of some complication, and Koop was just standing around waiting. The other thing that was different was that this particular gall bladder was not attached to the liver at all, but was just flopping around in the belly. When Rhoads continued to be delayed, Koop just went ahead and clipped off the gall bladder; more time elapsed. So he carefully sewed up the peritoneal layer, then the fascial layer, then the skin, stitch by stitch. He was standing there pretty pleased with himself when the doors finally banged open and Rhoads came charging into the operating room.

Koop offered some explanation in a faltering way, but Rhoads did not say a word. A large elbow on a huge arm silently but forcefully brushed Koop off to one side in a single movement. Rhoads then took out each stitch in the skin, then the stitches in the fascia, then the stitches in the peritoneum. He peered into the cavity, inspected the former bed of the gall bladder. Finding things in good order, he then resutured the peritoneum, then the fascia, then the skin. Without a word, he then strode from the room, leaving the future Surgeon General never to forget the lesson he had been taught.

Mind Your Manners

|

| Hoeffel |

In 1948 I was an intern at the old Pennsylvania Hospital, assigned for a while to the accident room. One of the accident-room duties of an intern is to sew up cuts and lacerations that arrive unexpectedly, but some lacerations can be out of your pay-grade and you have to call for help. On the evening in question, the victim had been so thoroughly slashed up that I had to call the chief surgical resident, Dr. Joseph Hoeffel. Hoeffel was big, tall, loud and self-assured, and swept majestically into the accident room with a little fellow trailing him. This follower seemed less than four feet tall but very quick and shifty. He didn't walk so much as he scuttled. Hoeffel bellowed, "Get out here!" and the gnome vanished.

While Joe was examining the laceration problem, the little fellow slipped through a different door to see what was going on. Most of us had the impression this guy might well be the one who inflicted the cuts, but in any event, he didn't belong where he was. "I told you to get out of here, and stay out," bellowed our surgeon. Again the scuttler scuttled away, while Hoeffel put on a sterile gown, sterile rubber gloves, mask, cap, and the whole ceremonial costume. He prepared to do his work, stamping out disease among the sick and injured, when a fist started at the floor. The little guy had slipped into the operating area once more, and soon the fist on the floor quickly flew in a wide arc, ending up on Hoeffel's jaw.

Hoeffel tumbled head over heels across the room, ending up in a corner. I don't think he was knocked out, but he was certainly dazed. The nurses called the police, who made a tumult of their own arriving to do battle. But the little fellow was gone, never to be seen again.

Fifty years later, I had occasion to preside over a meeting of the Right Angle Club, where

Hoeffel's son, the former congressman and current deputy member of the Pennsylvania Governor's cabinet, was the featured speaker. He looked remarkably like his father. I had to wonder if his father's lesson in diplomacy had made any notable effect on his progeny.

Funny Toes: A Physician Viewpoint

|

| Webbed Toes |

It probably took me twenty years to notice that, unlike most people, I had an incomplete separation of my second and third toes. I thought my toes were like everybody else's, but once you start peeking, you see that webbed toes are not normal, although they are not really rare, either. After another thirty years, it became apparent that most of my numerous descendants had the same kind of toe; it was obviously an inherited condition. When the family clan gathered at the beach, it was a source of mild amusement, possibly even a little pride. A few weeks ago, I happened to mention the matter at a party, whereupon another doctor promptly pulled off his shoes and socks, and revealed fused or webbed toes of a much more striking sort than mine; obviously, he was proud of it, too. He is of an old, old Philadelphia family that owns one of the oldest, if not the oldest, a house in Germantown. His family, too, is stigmatized in the same way only more so. In Philadelphia, when you are proud of your family, you are really, really, proud of it.

|

| Ainhum |

Which brings me back to my days as an intern in the accident room of the Pennsylvania Hospital. When there is a sudden crowd of emergencies in an emergency department, the nurses get all of them undressed, put in a hospital gown, and instructed to wait for the doctor behind a curtain that doesn't quite reach the floor. For some reason, as a medical student, I had been particularly struck by a photograph in a textbook of an inherited disorder said to have been first noted on a slave ship; the disease in the native language was named Ainhum. For reasons obscure, a tight little band appears at the base of the fifth, or little, too. It gets slowly tighter over a period of months, and eventually, the little toe falls off. That's all there is to Aihnum, and all that was known about it. So, imagine my surprise and delight to walk past a row of naked feet sticking out below curtains -- and there was my first and last case of Aihnum.

I summoned my colleagues, and the visiting medical students from both Jefferson and Penn who at that time shared training in our accident room. I raced off to my room to get a camera to record this momentous event. An elderly staff physician, either Tom McMillan or Charles Hatfield, wandered past and was invited to share the excitement. Well, he says, I saw one of those forty years ago, it looked just like that; old Doctor Norris showed it to me when I was an intern. Much murmuring ensued but abruptly stopped when the patient himself rose up and started putting on his clothes. He was going home, but why? "Well," he growled, "I came here because my back hurts, and all you people do is look at my toes!" He said he was going over to the Jefferson Hospital to get proper treatment, and I guess he did.

And finally, there is Morton's Toe. Or perhaps more properly, Mortons' Toes. There were in fact two Doctor Mortons, one of them at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons where I went to school, and the other at the Pennsylvania Hospital where I interned. In New York, Morton's Toe refers to a painful callous, or neuroma, that forms on the bottom of the victim's big toe. In Philadelphia, such an answer would get a failing grade, because the Philadelphia Morton had noticed that some people have a big toe that is shorter than the other toes, instead of being bigger as the term would suggest was proper. The tricky thing about this relatively harmless variant is that the big toe is actually not short at all. The foot bone, or metatarsal, is short, so the toe of normal length sits back farther on the foot and just looks shorter. The main significance is for shoe salesmen since the shoe needs to be long enough to avoid crushing the other toes.

So now, you readers who were not lucky enough to go to medical school can get a feeling for what it seems like to be a doctor. The other significant shared bond within the fraternity is a sense of outrage at the way health insurance companies drag their feet paying doctors, but that's not limited to feet..

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

A private investor has the general goal of accumulating enough wealth so, come what may, there will be a little left when he dies. If he has dependents or heirs, he needs somewhat more. Either way, he is not planning for perpetuity or thinking in astronomical time periods. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) had to switch his investment goals, in the 1920s, from investing for a comfortable retirement to investing for a perpetual art foundation. Perpetual.

|

| A bottle of Argyrol |

Having graduated from medical school (University of Pennsylvania) in 1902, and then writing a doctoral thesis in chemistry and pharmacology at the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, Barnes invented a patent medicine that quickly made him rich. Argyrol was a mildly effective silver-containing antiseptic with the unfortunate tendency to turn its users permanently slate-gray. The advent of antibiotics has since made Argyrol almost sound like quackery, but it was effective enough at the time to require factories in America, Europe, and Australia, and Barnes became immensely rich with it. The American Medical Association strongly disapproves of physicians who patent remedies, so Barnes was never held in high regard by his colleagues; but it could well be argued that he had as much training as a chemist as a physician, and spent his entire professional life as a chemist, manufacturer, and investor.

|

| The Barnes Gallery |

Barnes was eccentric, all right, but on Wall Street, the saying goes, "What everyone knows, isn't worth knowing." Guided by that principle, in 1929 he sold his company at the very peak of market euphoria, getting out of common stocks at the top of the market. It is small wonder that he soon instructed his Foundation to invest its endowment entirely in bonds. During the 1930s, commodities were extremely cheap because no one had any money. Barnes, of course, had a potful of money and bought hundreds, even thousands, of artworks very cheaply. He also bought 137 acres of Chester County, PA, real estate, and a 12-acre arboretum in Merion Township on the Main Line. Although he is famous for acquiring hundreds of French Impressionist paintings with the advice of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, he also bought great quantities of Greek and Roman classical art, African art, and the art of the Pennsylvania German community. He picked up a notable collection of metallic art objects. Most of these "losers" are down in the basement because he had so many Renoirs, Matisse, and Picasso (some of them may be worth $200 million apiece) that the upstairs galleries were pretty well stuffed with them. Viewed from the perspective of an investor with a goal of perpetuity, of course, the things in the basement just happen to be temporarily out of fashion, just like those bonds in the portfolio.

|

| A view inside the Barnes gallery |