0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Benjamin Franklin Parkway

Benjamin Franklin Parkway

|

| Walking Tour Parkway |

Philadelphia Chromosome

Every Spring for the last 185 years, the Franklin Institute has honored the most distinguished scientists alive; Franklin would certainly be proud of the Institute named after him. In recent years, many awards were combined into two categories, the Bower Awards and the Benjamin Franklin gold medals. Unlike the Nobel Prize, the Franklin Institute Medals are not given for eminence in a designated field of science, but rather are given out by a hard-working committee of scientists who ask themselves What are the really hottest scientific fields at present, and then ask panels of international referees Who is most eminent in that field? The awards thus effectively avoid fields that are temporarily stale and static, by being unrestricted in advance to particular fields. The approach of searching for the greatest minds rather than greatest achievement may well lead to the same award, but the method of choice seems more harmonious with the spirit of Benjamin Franklin, who not only excelled in the field of electricity but actually invented that whole field. The subtle shift in emphasis seems to have been well received; this year's Awards Banquet was over-subscribed before the invitations were printed, and a capacity audience of 800 attended a superb reception, dinner and audio-visualized live ceremony. Actually, the ceremony extends for a whole week, with scientific symposia and in-person meetings with high school students designed to interest them in science.

This year eleven scientists, the most prominent of whom were Bill Gates and Peter Nowell, received the medals. We'll get to Bill Gates in a while; for the present, let's concentrate on Peter Nowell, who invented the Philadelphia Chromosome. What's that?

|

| The Philadelphia Chromosome |

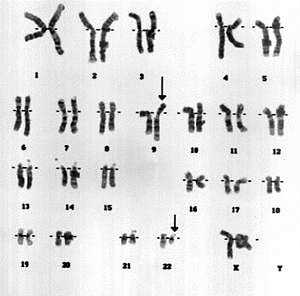

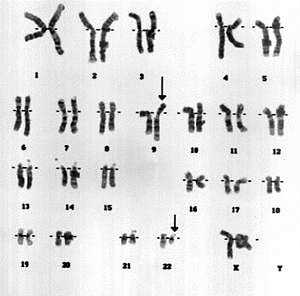

Well, from 1921 to 1955, it was generally held that people, members of the human race, contained 48 chromosomes in every cell in their bodies. The chromosomes were thought to contain the genetic code governing our biological construction, explaining the difference between us and fruit flies, which for example only have four chromosomes per cell. After painstakingly examining the appearance of the chromosomes in different people and in cancer cells, it was then generally held that cancers never seemed to have any genetic abnormality. After all, the chromosomes of cancer cells looked exactly like those in normal tissue: Forty-eight chromosomes, never differing in cancers, so go look somewhere else for the cause of cancer. Unfortunately, the state of scientific development fifty years ago can be summarized by noting that about that time it then became established we really only had 46 chromosomes, not 48. As for cancer, the M.D. pathologist Peter Nowell, then noticed in 1956 that a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia had an extra translocation on one particular chromosome, giving it a funny shape. This translocation was furthermore present in every single other leukemic cell suggesting that one cell had somehow undergone a single mutant change, and all the rest were its descendants. At least in CML (chronic myelogenous leukemia), it suddenly looked as though the cause had been found since the further study revealed the same was true of just about everyone who had CML. At first, it was felt that while maybe the cause of this particular type of cancer had been found, every other cancer might still be caused by something else. Not so. From believing no cancers were genetic in origin, Peter Nowell started us on the path of now being confident all cancers have a genetic cause.

|

| Dr. Peter Nowell |

How could we all have been so wrong; can't scientists even count up to 46? No, as a matter of fact, in 1955 it was pretty hard. If we couldn't even tell how many of them were there, it's obvious the comment they all looked alike wasn't worth very much. As Peter shyly admits, his discovery was a result of being trained as a physician rather than as a life scientist; he knew what leukemia looked like, but at that time he didn't know very much about chromosomes. It happens chromosomes spend most of their lives expanded into tiny filaments too small to examine under the microscope. But as they enter the stage of cell division called metaphase, those filaments shorten and thicken up, becoming a lot easier to examine. As a pathologist, Peter didn't bother to stain his slides in dilute salt solution, but just washed them in tap water. The tap water had caused the cells to swell up and burst; those that happened to be in metaphase dumped their stubby chromosomes out where they could be stained and looked at. Simple. Doesn't everyone wash slides in tap water?

So fifty years ago, the general question of what causes cancer finally narrowed down to the right sort of specific question. Thousands of scientists, spending billions of dollars from the National Institutes of Health, sharpened the focus of their search considerably. It certainly looks as though someone is going to carry the search the final step, pretty soon. However, the fact that fifty years of intensive study still hasn't quite found the answer is an illustration of how fiendishly difficult the search really is. Each year that might have been spent futilely avoiding genetic searches would have added one year more before the answer was finally found. By the way, why is it called the Philadelphia Chromosome? In 1955 it had been decided by the scientific community that every genetic abnormality would be named after the city in which it was discovered. Dr. Peter C. Nowell of the University of Pennsylvania and the late Dr. David Hungerford of the Fox Chase Cancer Center were the joint discoverers, so obviously it was entirely a Philadelphia discovery; at that time it had been made a custom that genetic abnormalities were named after the city where they had been first found.

It would be a mistake to conclude that nothing new has been discovered in half a century of research. It has been established that not only Myelocytic Leukemia but essentially every cancer starts with some genetic abnormality, which triggers the expression of "mini RNA". These abnormalities then apparently express a cancer-producing action by triggering an abnormal factor in the cell signaling system, called tyrosine kinase. Drugs with the effect of paralyzing that enzyme have been found to be curative in 95% of cases of chronic myelogenous leukemia, and some other forms of lymphoma. We're certainly getting closer, step by unexpected step, to the answer. In fact, we may be getting even closer to a point where drug research can jump to seeking cures without precisely defining how the cancer was caused. After all, if cancer is caused by a chain of cellular events, it may not matter where you break the chain. That realization appeared with, first aspirin and then the statin drugs, for treating heart attacks and strokes, even though we are still not completely clear about how atherosclerosis is produced. Meanwhile, the death rate from hardened arteries has dropped by half.

It wouldn't be right to omit mention of Peter Nowell's Quaker heritage. Although he isn't a Quaker, his mother was a Matlack, a direct descendant of Timothy Matlack, the Haddonfield Quaker who was the scribe for the first writing of the Declaration of Independence. Sitting in silent Quaker meeting, polishing and simplifying one's message before delivering it, is very good training for a habit of simple, direct thought. As Dr. Nowell phrases it, he is a chronic "lumper" of ideas, when so many scientists are content to be "splitters". Splitting complexity into its essential components is a useful approach. But somewhere, someone has to get to the heart of the matter.

Lumpers In Constant Combat With Splitters

|

| James Boswell's Book |

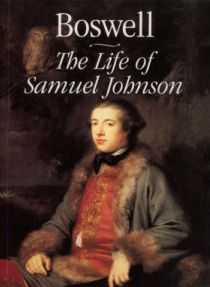

Some colleges produce managers by teaching management theory, but in certain Ivy League colleges it is thought to be more useful to teach how to dominate a committee, eventually perhaps a board of directors, or a board of trustees. The handbook of instruction is James Boswell's Life of Johnson which is a rather large book of verbatim notes that Boswell took of his many lunches at a London club in the 18th Century. Boswell was a quiet mouse privileged to sit in the company of the great Dr. Samuel Johnson, surrounded by the most eminent intellects of the Enlightenment. Boswell carefully manages the background of each episode, describing the issue and the various arguments, and then -- Sam Johnson's booming voice settles the matter. After he speaks, the meeting is over.

|

| Dr. Samuel Johnson |

"Why, sir", says Johnson, and then look out for the one-liner to follow. We get the impression that Dr. Johnson used that "Sir" signal to indicate he had enough of these dumb arguments, and soon would come the growled epigram that scatters any token resistance. Boswell may have neglected to record instances where the great Johnson was defeated in debate, who knows. We are left with the distinct impression that if you engaged in lunch table conversation with Sam, you were almost certain to lose. So that's what Ivy League students are being taught: how to win a debate at a committee meeting, in the expectation they would spend much of their lives in committees, boards, and even cabinets. That's how the English-speaking world gets its work done and its decisions made. That's what lunches at the Franklin Inn Club, or the club tables of the Union League, are trying to do for the education of neophytes.

As the goggle-eyed student of the great Chauncey Tinker, who gave young Pottle his start in life, it was an awesome performance for me to watch. But the rules of this game never became entirely clear to me, I'm afraid, until the other evening when I listened to Peter Nowell describe in a half-dozen brief paragraphs how he had revolutionized prevailing theories of the cause of cancer. The Franklin Institute then followed the award ceremony by putting on an all-day symposium of notables who run elaborate enterprises in cancer research, essentially funded by the National Institutes of Health, your tax dollars at work again. Last year, the NIH dispensed thirty billion -- you heard me -- dollars in research grants to internationally known research entrepreneurs, and if you can stay awake during their talks, there must be something the matter with you. So far as I could see, they were painstakingly describing every grain of sand on the beach, whereas Peter Nowell made the whole beach electric and clear in ten minutes. Essentially, he was saying that each patient's cancer is caused by a long chain of events, starting with a single mutation within a single cell. All the other cancer cells of a patient are descendants of that first one, which triggered the cascade of chemical events now repeated by the descendants. To stop the process, you probably only have to find a way to break the chain at one vulnerable point. Then you have a cure, without necessarily understanding every other link in the chain.

Peter Nowell described himself as a "lumper", admitting that most scientists are "splitters". A splitter quite reasonably attacks a complex problem by isolating one small piece of it at a time; that's really a pretty good way to address overwhelming complexity when you encounter it. But you can be sure that people of that mindset should not be found in a President's cabinet, deciding how to save the world from impending disaster. Whether by their own genetic predisposition or as a result of peer pressure in their profession, they are habitual splitters. And it suddenly occurred to me why Sam Johnson's one-liners always won the argument; he was a lumper. Usually right, sometimes wrong, never in doubt. Witty as a Frenchman, but as quick as a rattlesnake. Cordial, perhaps, unless you disagreed with him.

We need more lumpers. If they get that way from the likes of Chauncey Tinker, we need to print more copies of The Life of Johnson. If they are born that way, maybe we need a breeding farm for lumpers, which is what the Assembly Ball amounts to. But don't get me wrong, we need more splitters, too. They just have to learn their place at the table.

Rara Avis

|

| The Academy of Natural Sciences |

School children grow up in Philadelphia with an image of the Academy of Natural Sciences as a place to visit dinosaurs. Indeed, it does have on display the first dinosaur skeleton ever to be discovered, as well as a number of others. However, only about a third of the building complex on Logan Circle is devoted to public museum displays. The rest is devoted to specimen storage, library and scientific work of the highest scientific eminence and value. In the scientific area, the most striking thing to a visitor is to notice how few windows there are. Scientists often spend their time looking through microscopes, so they don't care about windows. In a skyscraper business office that wouldn't be acceptable at all and the staff would all get the heeby-jeebies and quit. In the business world, the number of windows your office has is important, especially if they are corner offices, the best kind.

|

| Humming Birds |

In one small area of the museum is a set of ingenious metal cabinetry containing 200,000 bird specimens, including every one of the 10,000 known species of birds on earth. In fact, about a quarter of all the "type" specimens are found there with red tags on their feet. A type specimen is the first known and described specimen of that particular bird, ever. That's a round-about way of relating that this is where Ornithology, the study of birds, began. It also tells you that when bird skins are treated with arsenic salts, they last a very long time; a considerable number of the specimens in the cabinets were contributed by Audubon, himself. New bird skins are acquired at the rate of a thousand a year, related to the scientific studies which go on, studying bird diseases, genetic changes due to environmental changes, and pollution effects. The recent uproar about Avian influenza revolves around the tendency for bird diseases to undergo genetic changes themselves and become human diseases. A great many such bird diseases are maintained at the laboratory in case they are needed for a crash program of vaccine development. Environmentalists will be surprised to learn that the mercury content of bird feathers has actually declined in the past century.

|

| Guinea fowl |

With a good guide you quickly grasp the attraction of this topic of birds and birding. There are huge condors, with six-foot wingspreads; and one-inch hummingbirds. Birds of every shape and coloring, reaching some sort of extreme with the Bird of Paradise from New Guinea. Owls and eagles, ducks and chickadees. Hummingbirds defy the usual sort of nets; every single little hummingbird specimen was obtained by shooting it with a special little gun. If you see a hummingbird in your garden, just imagine what skill it takes to shoot one.

The ornithology department maintains an active program of loaning bird specimens to scientists all over the world, although this activity has recently been affected by computerization of the catalog of specimens, resulting in a massive global internet conversation among ornithologists, sort of like a Facebook of a very special sort. For all this activity going on, the collection area is an eerily silent place.

And that's just birds, crammed into an organized space of, well, maybe fifty by two hundred feet, eight feet tall, fifty shelves per typical cabinet. Right next to it is the insect collection, perhaps taking twice the cabinet space. Insects are a lot smaller than birds, so each shelf has more specimens. That sounds like an awful lot of Latin names to try to remember. And a certain amount of danger, too. Several scientists died of arsenic poisoning before the full hazard was appreciated and contained.

Proposal for the Parkway

|

| Alvin Holm |

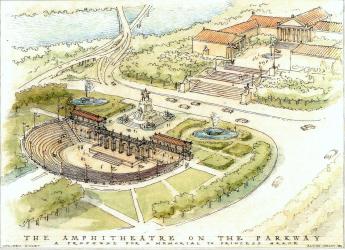

Architect Alvin Holm spoke recently about an idea he had dreamed up in 1986, for an amphitheater in the Eakins Oval, right in the middle of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. At that time he envisioned it as a memorial to Grace Kelly, but Monaco wasn't interested, and the City was broke. But times change, neighborhoods change, and maybe the idea needs to be re-examined.

A bit of history needs to be refreshed. Around 1900 when the Parkway was dreamed up, Philadelphia was said by some local boosters to be the richest city in the world. That may have been a little overoptimistic, but it was nearly true enough that no one laughed loudly when it was enunciated. The Parkway was envisioned as a new departure to transform the whole city from square blocks of red-brick buildings of Georgian style, into a classical French version of grand elegance. To emphasize the new departure, it cut a diagonal from City Hall to the Art Museum, uniting these two French architectural monuments into a transformational classic boulevard. It wasn't just an imitation of Champs Elysees, it was a design by the very same architects, intended to lead the centers of many great cities of the world into modernized versions of the Roman Forum. Paris somehow managed to get away with it in time, but the 1929 crash stopped Philadelphia's dreams dead in their tracks, and the city just didn't recover.

Consequently, vast stretches of North and West Philadelphia were abandoned, then transformed into slums as poor people sought cheap housing. If you just look at Baltimore and Newark, you can easily see how sudden reversals can destroy a city completely. Philadelphia retreated into Center City, surrounded by an inner ring of slums, which were in turn surrounded by a ring of newer suburbs. The automobile hastened the flight to the suburbs, while the business district retreated to the inner core of Center City. In order to protect the Shining City on a Hill from being completely disrupted, informal barriers were sought, and the Parkway became one of them. They weren't walled moats, but they served the same purpose. Therefore, during the long decades of limping along, occasional cries of, "Why don't we make the Parkway into a grand boulevard?" had a silent, sullen answer. We weren't really sure it was a good idea. It didn't fit within our revised circumstances.

|

| The Amphitheatre on the Parkway |

But the City is now getting back on its feet, as anyone who has noticed the astonishing restaurant revival of Fairmount Avenue, or of Old Towne, or Society Hill, and the rebuilt "Chinese Wall" leading to and from the old Broad Street Pennsylvania Railroad station, can easily see. The Independence Mall and the University of Pennsylvania areas were largely built with Federal Money, but no matter, the transformation is still evident, the tide has turned. So Alvin Holm got out his drawings about premature dreams we couldn't afford, and asked, "Is it time?"

The unfinished Ben Franklin Parkway has cut its path, willy-nilly, through the neighborhoods, the trees have had time to grow, the museums time to migrate. The childless couples of the metropolitan area were coming back in town to enjoy the restaurant revolution and the theater revolution. Alvin Holm was getting a little older but not less energetic. He remembered that at the foot of the Art Museum was a statue of George Washington on a horse, and behind our First President was a big expanse of empty land. To build an amphitheater only took bulldozers, and could seat a thousand people. If you were as lucky as the ancient Greeks, and possibly if you built in precisely the same way, a speaker in the center could be heard -- without artificial amplification -- if he whispered, by everyone in the amphitheater audience. If you do use electronics, there's plenty of space in back of General Washington for a dignitary to give a speech on a raised platform, and there's enough empty audience space in a wider sweep, for fifty thousand people to congregate and listen. To him, or to a rock band, or whatnot. There aren't very many places left on earth in the center of a big city, where a single person can stand against a magnificent classical background, and be heard by fifty thousand chanting, hollering true believers. All of this could be accomplished by essentially digging a hole in the ground and closing off the area to traffic. But oh, yes, it takes one more thing. You have to want to do it. So let's consider for a moment who else covers the neighborhood, waiting for the right time to make a move.

|

| Amphitheater Sketch |

Instead of regarding Fairmount Hill as just a big obstacle to automobiles trying to get home, let's just see what some others are thinking. For example, the people who run Drexel University are seriously talking about buying the air rights above the railroad marshaling yards on the west bank of the Schuylkill, and putting up a major business district and residential complex. They are thinking mainly of reviving West Philadelphia, and that's fine, but another bridge at that spot is badly needed to divert traffic around the present choke point on the Schuylkill Expressway, and that's also fine. Put some paths down to the river from the Art Museum to meet a new pathway to the Drexel development, as well as the recreational area along the river, and you could really have something pretty nice for the commuters who would otherwise begrudge the cost of digging an amphitheater hole in back of G. Washington.

Looking to the north of the Art Museum, there's a second small mountain with Kelly Drive between the two. At one time, both hills had reservoirs on top. The Art Museum demolished one reservoir, but the other reservoir is still there. It's a fifty-acre lake surrounded by dense forest; but from the inside look back over the top of the trees and you can see skyscrapers, almost right next to you. It's been adopted by migratory birds as part of the Atlantic flyway, and you would just be amazed at the hawks and ducks and all manner of other little black jobs that fly around and get recorded by bird watchers. The lake is full of fish, probably originally dropped by passing birds. The Audubon Society has a fundraising project going on, right now, to build a visitors' center in the forest, in conjunction with Outward Bound, the rock climbers group. Go to the left and you are overlooking the races at Boathouse Row, turn in the other direction to see Girard College, the hospital complex, and the further north you get to Temple University.

And one more thing. The old B&O Railroad once snaked along the Schuylkill and turned right around the (now) Art Museum, through tunnels over to Spring Garden Street, and down to Reading Terminal. Just what to do with this ditch running through the center of town unnoticed, is beyond my scope. Let someone else have a chance at being a visionary, but it must be remembered that New York City recently had a similar relic on its hands, and made something pretty nice out of the West Side of their town.

All of this potential even has the danger that projects will collide with each other, so it would sound like a nice idea for some Foundation to put together a planning board, to fit it all together without getting mixed up in politics, or squabbling over who will run things. But even that fuss would be a novelty, a nice thing to have for a while.

Barnes Foundation -- Drawing a New Moral

|

| Andrew Stewart |

Andrew Stewart, the Public Relations Director of the Barnes Foundation, and for thirteen years a member of its Board of Directors, recently addressed the Right Angle Club. He gave a new slant to the quarrelsome saga of Dr. Barnes' will, offering the point of view in favor of moving the paintings to the Parkway. It's useful to hear the legal and historical background because about all we hear are criticisms, balanced by joy at having the famous paintings where we can see them.

Essentially, the will declared a wish for the School and Museum to follow the original indenture. After the passage of time, the old board members died off, and the new board members found the Indenture to be out of date, like specifying the purchase of railroad bonds. Delivered in a charming Scottish brogue, the argument was fairly convincing. But it stimulated in me an entirely different moral from the eternal dispute between the right of a man to have respect paid to his expressed wishes for his own property, versus the self-defeating quality of the same restrictions with the passage of time.

|

| Barnes Foundation |

Barnes was born in Kensington, and had a hard life as the son of a Civil War veteran who lost an arm in the war, and had a dismal time making a living as a butcher. Barnes was his fighting-spirit son, who worked his way through medical school. It was Jefferson Medical College, where I was on the faculty for decades. While it is true his patent medicine gave a permanently sickening color to the children who were treated for sinusitis, it is also true that in the form of eyedrops it prevented the transmission of syphilis to millions of newborn children. In that view, it was a real scientific contribution, although the medical profession continues to take a dim view of doctors advertising their wares. Although he was himself a failed artist, Barnes was a highly successful collector of (then) modern art and started a school with John Dewey to teach art appreciation to poor people. One by one, the local universities snubbed his wishes for an art appreciation school, and the local Philadelphia museums were pretty sniffy about his favorite artists.

In fairness to them, Barnes was probably pretty pushy in his demands. Unfavorable local reception to an exhibition which had received rave applause in Paris, convinced Barnes he was right and they were wrong. After this, Barnes developed a lasting hatred of Philadelphia and all its stuffy ways; he definitely didn't want his own impressionist art to be in Philadelphia, which would never appreciate it. While Philadelphia finally woke up to the value of Impressionist painting, Barnes never relented while he was alive. I hope I give a fair portrayal of the argument except for the politics and the legalities, that I know very little about.

But hearing the arguments, I see an entirely different moral to the saga. Ever since the inflation of the 1930s, fine art has appreciated in value, faster than the endowments to maintain the art. (That's probably a useful tip to investors, too.) It's fairly standard for a wealthy person to donate his art collection, plus a sum of money to endow the maintenance of the art. Most of the time, the size of the endowment is carefully calculated to grow at least as fast as the value of the paintings, because you have to ensure them, and pay for increased security, and increasing attendance. With the new trend toward inflation of at least 2% a year, the old premises don't work anymore, and the endowment eventually runs out. At that point, it runs into restrictions which -- to be perfectly blunt -- were created to prevent the trustees from pilfering the museum. A museum may not sell its art to pay for administrative expenses.

Consequently, The Barnes ran into a situation where it had billions of dollars worth of paintings in the basement, which it could not sell, and could not even hang in the museum because of Barnes' specifications for what went on the walls. This situation isn't going to change, because a dollar in 1913, when the Federal Reserve was created, is now scarcely worth more than a penny. And the present Fed is committed to 2% inflation, forever.

So, how about this: let the lawyers who write wills, and the Orphan's Court which administers them, insist that the art collection be divided into two parts. One would be the permanent collection, just as at present, and the other would be eligible for sale in the judgment of the Orphan's Court.

5 Blogs

Philadelphia Chromosome

Just about everybody has 46 chromosomes in every cell in the body. Some people have more than that: they have the Philadelphia Chromosome.

Just about everybody has 46 chromosomes in every cell in the body. Some people have more than that: they have the Philadelphia Chromosome.

Lumpers In Constant Combat With Splitters

The home dinner table is no longer the place most families teach the rules of conduct to each other, probably because of the invasion of homes by television. But there are places where friendly debate is still conducted and social issues are settled. In Philadelphia, newcomers are still taught what's what, in this manner.

The home dinner table is no longer the place most families teach the rules of conduct to each other, probably because of the invasion of homes by television. But there are places where friendly debate is still conducted and social issues are settled. In Philadelphia, newcomers are still taught what's what, in this manner.

Rara Avis

The Academy of Natural Sciences is one of the great jewels of Philadelphia, and like the rest of the city, cringes from publicity but needs it badly.

The Academy of Natural Sciences is one of the great jewels of Philadelphia, and like the rest of the city, cringes from publicity but needs it badly.

Proposal for the Parkway

In 1986 the architect Alvin Holm proposed an amphitheater for the Parkway. It was too soon, but maybe its time is approaching.

In 1986 the architect Alvin Holm proposed an amphitheater for the Parkway. It was too soon, but maybe its time is approaching.

Barnes Foundation -- Drawing a New Moral

Inflation makes for a new slant on the saga of the Barnes Foundation.

Inflation makes for a new slant on the saga of the Barnes Foundation.