0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Gardens Flowers and Horticulture

Gardening, flowers and the Flower Show are central to the social fabric of Philadelphia.

Fernery

|

| Gardeners |

As explained by the curator of The Morris Arboretum, there are a few other ferneries in the world, but the Morris has the only Victorian fernery still in existence in North America. That doesn't count a few shops that sell ferns and call themselves ferneries; we're talking about the rich man's expensive hobby of collecting rare examples of the fern family in an elaborate structure. That's called a Victorian fernery. The one we have in our neighborhood is really pretty interesting; worth a trip to Chestnut Hill to see it.

Although our fernery was first built by the siblings John and Lydia Morris, it was rebuilt at truly substantial cost by the philanthropist Dorrance Hamilton. It is partly above ground as a sort of greenhouse, and partly below ground, with goldfish and bridges over its pond. Maintaining an even temperature is accomplished by a complicated arrangement of heating pipes. The temperature the gardener chooses affects both the heating bill and the species of fern that will thrive there. You could go for 90 degrees, but practical considerations led to the choice of 58 degrees. The prevailing humidity will affect whether the fern reproduction is sexual or asexual, a source of great excitement in 1840, but survivors of Haight-Asbury are often more complacent on the humidity point.

There are little ferns, big ferns, tree ferns, green ferns, and not-so-green ferns; the known extent of ferns runs to around five hundred species. Not all of them can be found in Chestnut Hill, what with humidity and all, but there are enough to make a very attractive and interesting display. For botanists, this is a must-see exhibit. For the rest of us, it's probably the only one of its kind we will ever see, a jewel in Philadelphia's crown, and shame on you if you pass it by.

Gardening Survives

Adam Levine, the author of a new book about the Philadelphia public garden scene was recently the featured guest speaker at the Franklin Inn. He's a charming person, and has given us a great book.

He draws to our attention that the Philadelphia region is pre-eminent in the garden world, and has been so for several centuries. While it is true that Philadelphia has a mild enough climate to be suitable to two climate zones, the early settlers came from a region of middle England that has been a garden center since Roman times. And they were Quakers, uncomfortable with the outward show in buildings and furnishings, but flowers were innocent instruments of the display. Although Chanticleer was created by a Pennsylvania German family, the great centers of public gardens are mostly traceable to the influence of Quakers, and the du Pont family. Since one or two years of neglect will ruin almost any garden, the essence of great gardens lies in the ability to survive.

|

| The Horticultural Society |

In fact, the Philadelphia area contains hundreds of gardens which have decayed and virtually disappeared. The Horticultural Society is at the heart of garden preservation, financed in large part by the annual flower show, but even that thriving organization is hard pressed to do justice to the vast areas that need tending. Woodlands would be an example of an area needing tending, and Friends Hospital is an object lesson. When that venerable institution was sold to sharp pencil types from out of town, the Azalea gardens on the grounds were closed to visitors, except for two hours a year. It makes you tremble to imagine how long this famous azalea collection will probably survive. Meanwhile, Germantown's famous gardens are maintained in a minimal way, stretching the resources of the owners who have more urgent demands to meet in their buildings and furniture. Indeed, it is hard to name a really outstanding garden within the city limits, with the exception of the Morris Arboretum, which barely makes it within city boundaries. The area back of the Art Museum along Boathouse Row makes a brave attempt in the spring, but it's a pale reminder of the glory which used to be seen in East Fairmount Park, especially at Lemon Hill, Stenton, and Cliveden. Stotesbury is just a relic.

|

| Morris Arboretum |

Gardens have moved to the suburbs. Chanticleer, the Morris Arboretum, Longwood Gardens, Nemours, the Scott Arboretum at Swarthmore, West Laurel Hill, The University of Delaware in Newark, Cabrini College in Villanova, Haverford College Arboretum, Temple University's Ambler campus, and the Trenton Sculpture Gardens on the old fairgrounds -- all would demand mention in any list of outstanding gardens in America. But only a few of them aspire to the standards of an outdoor sculpture garden, where the goal was to surround each piece of sculpture with a garden in such a way that only one sculpture could be seen at a time. Now, that was gardening on the grand scale.

Hidden in a regional garden scene is the seed merchants, starting with John Bartram and famous under the Burpees, which make gardens possible. After all, there has to be a place to find these things. Perhaps the catalog stores, like Wayside Gardens, are the hope for the future. Every shrub or tree transported from a nursery takes up a ball of topsoil along with the specimen, and the appearance of nurseries around the periphery of a city is usually the first step in the development of housing projects. If there is an investment of topsoil in every garden, perhaps we ought to think a little bit about the way we let the investment dry up and blow away.

REFERENCES

| Gardens of Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley William Klein Jr. ISBN-10: 1566393132 | Amazon |

Quaker Gray Turns Quaker Green

|

| American Friends Service Committee Logo |

Miriam Fisher Schaefer, at one time the Chief Financial Officer of the American Friends Service Committee, had to cope with the economics of renovating the business headquarters complex for various central Quaker organizations. They're housed in a red-brick building complex, naturally, located on North 15th Street right next to the Municipal Services Building of the Philadelphia City Hall complex. The original building within the complex is the Race Street Meetinghouse, funds for which were originally raised by Lucretia Mott. The Quakers needed to expand and renovate their offices, a nine million dollar project. Miriam, a CPA, calculated that the job could be made completely environment-friendly for an extra $3 million. The extra 25% construction cost explains why very few buildings are as energy-efficient as they easily could be. However, in the long run, a "green" building eventually proves to be considerably cheaper. Not only would a green Quaker headquarters be a highly visible "witness" to environmental improvement, but it would also pay for itself in reduced expenses after about eight years. That is, if friends of the environment would provide $3 million in after-tax contributions, they would provide a highly visible example to the world, and reduce the running expenses of the Quaker center by a quarter of a million a year, indefinitely. Effectively, this is a charitable donation with a permanent tax-free investment return of 12%, quite nicely within the Quaker tradition of doing well while doing good.

|

| Rockefeller Center |

Energy efficiency isn't one big thing, it is a lot of little things. If you dig a well deep enough, its water will have a temperature of 55 degrees, and only require heating up another 15 degrees to be comfortable in winter, or cooling down thirty degrees to be comfortable in the summer; that's described as a heat pump. Then, if you plant sedum, a hardy desert succulent plant, on the roof it will insulate the building, slow down rainwater runoff, and probably never have to be replaced. Rockefeller Center, you might be interested to learn, has a "green roof" of this sort, which has so far lasted seventy years without replacement. The Race Street Meetinghouse was built in 1854 and has so far had many roof replacements, each of which created a minor financial crisis when the need suddenly arose.

The ecology preservation movement is full of other great ideas for city buildings because buildings --through their heating, ventilating and air conditioning -- contribute more carbon pollution to the atmosphere than cars do. For another example, fifty percent of the contents of landfills originate in dumpsters taking construction trash away from building sites. What mainly stands in the way of more recycling of such trash is the extra expense of sorting out the ingredients. Catching rainwater runoff allows its reuse in toilets, eliminating the need to chlorinate it, meter it, and transport it from the rivers. And so forth; you can expect to hear about this sort of thing with great regularity now that the Quakers have got stirred up. You could save a lot of air conditioning cost by painting your roof white. At first, that would look funny. But do you suppose oddness would bother the Society of Friends for one instant? No, and you can expect them to make it popular, in time. People at first generally hate to look funny, but with the passage of time they grow to like looking intelligent.

A lot of people want to save the planet. So do the Quakers, but they have come to the view that the public is more easily persuaded to save money.

Delaware Bay Before the White Man Came

Captain John Smith of Virginia, sometime friend of Pocahontas, wrote a letter to Captain Henry Hudson that he understood there was a big gap in the continent to the North of the Virginia Capes, and maybe this was the Northwest Passage to China. Hudson set out to look for it.

|

| Hudson |

Smith's misjudgment now seems like a credible story if you take the ferry from Lewes, Delaware to Cape May, New Jersey. You are out of sight of land for half an hour on that trip, and it's a hundred miles of blue salt water to Philadelphia if you decided to go in that direction. In fact, the bay widens out to double the width or more, just inside the capes, and you can see how an explorer in a little sailboat might believe there was clear sailing to the Indies if you went that way. But as a matter of fact, Hudson encountered so much "shoal" that he ran aground repeatedly trying to sail into the bay, and soon gave up. He encountered a swamp, not an ocean passage. The Hudson River, and later Hudson's Bay, seemed like better bets.

What Hudson had encountered was one of the largest gaps in the chain of Atlantic barrier islands, formed by the crumbling of the Allegheny Mountains into the sea, and then washed up as beach islands by the ocean currents. At various points, the low flat sandy islands became re-attached to the mainland as the intervening bay silted up, and that's why the islands of New Jersey and Delaware seem like part of the mainland. And that's what would have happened to the whole Delaware Bay if it hadn't been ditched and dredged, and wave action diverted with jetties. The swamp was a great place to breed insects, so fish were abundant, and that brought birds in vast numbers. Two stories illustrate.

|

| Horseshoe Crabs |

Once a year, a zillion ugly Horseshoe Crabs crawl out of the sea onto the Lewes beaches, and lay a million zillion eggs in the sand. Almost to the moment, a swarm of South American birds swoops out of the skies to eat the eggs. Those birds started flying months earlier from thousands of miles away, but their timing with regard to Delaware crab eggs is perfect, so this evolutionary semi-miracle must have been going on for many centuries.

|

| Cape May |

Now, coming from the other direction, every hour each fall it is possible to see a hawk or two flies south to Cape May, then sort of disappearing in the woods. And then, at some unknown signal, tens of thousands of hawks rise from the bushes and travel together on the thirty-mile passage over the bay and then go on South. Cape May has lots of migratory birds and bird watchers, and it also has Cape May "diamonds", which are funny little stones washed up at the tip of Cape May Point.

In the spring, vast schools of successive species of fish migrate up the Delaware Bay to spawn in the reeds along the shoreline, but as each school encounters the point where the salt water turns fresh, they stop dead. They mill around at this point for several weeks adjusting to the change of water and then go on about their business. While they are there, it is possible for amateurs to catch amazing amounts of fish, if you know the best time, and if you know where the salinity changes. Since heavy or light rainfall can shift the salinity barrier fifty miles, you have to own your own boat if you want to enjoy this phenomenon, since the rental boats are all spoken for months in advance. Fishermen don't like to tell you about such things; patients of mine who literally owed me their lives have refused to say where I might find the fish this year.

Over on the New Jersey side of the bay, oysters like to grow, although something has just about wiped them out in recent decades. There is a town called Bivalve, which is worth a visit just to see the towering piles of oyster shells left over from last century. For miles around, the roads are actually paved with ground-up oyster shells. Up north around Salem, the shad used to run by the millions until the warm water emerging from the Salem (nuclear) power plant attracted them into the intake pipes and action was taken to abate the nuisance. The Salem Country Cub is one of the few places where planked shad can be obtained in season. The system is to split the fish open and nail it to a board, which is then placed in the big open fireplace to cook, and sizzle, and smell just wonderful good. On the other hand, if you want to buy shad in season (March-May) and cook it at home, the place to get it is in Bridgeton.

At the far northern end, at Trenton, the real Delaware River flows into the bay. The area has long since been dredged, but at one time the "falls" at Trenton were notable. Even today, if you travel upriver almost to Lambertville, you will see the river drop over several small ledges. Actually, rapids would probably be a better descriptive term, since Delaware picks up quite a strong current coming down from the Lehigh Valley. In seasons of heavy rainfall, the falls can be completely "drowned".

And down at Philadelphia where we live, the Schuylkill joined Delaware, forming the largest swamp of all at the river junction, a place once famous for its enormous swarms of swans. The Dutch discovered a high point of land at what is now called Gray's Ferry and made it into a trading place for beaver skins from the local Indians. There seems no reason to doubt the report that they took away thirty thousand beaver skins a year from this trading post, now the University of Pennsylvania.

An English sailing vessel was once blown to the East side of Delaware at what would now be Walnut Street in Philadelphia, and it was recorded in the ship's log that it was scraped by overhanging tree limbs. The high ground at that point seemed like a favorable place to situate a city because the water was deep enough for ocean vessels. They had stumbled on one of the relatively few places in the whole bay that was both defensible and navigable, where the game was abundant, and fishing was good. The rest is history.

Gardening

|

| Charles Burpee |

The late Charles Burpee had a little speech he made everywhere he got a chance. "If you want to be happy for a day," he said, "Get drunk." If you want to be happy for a month, get married. But if you want to be happy for a lifetime -- get a garden." A lot of people who were born and bred in condos think Burpee must have been a little strange, but even they often tend house plants and window boxes.

Gardening not only takes time, it takes time during the day.

|

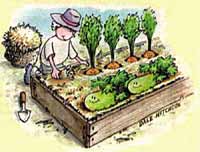

Gardening may be fun, but it takes time. It particularly takes time during daylight without rain, which is in much shorter supply during short springtime days, and equally short days in the harvest season. In fact, the most critical part of home gardening is to do your planting and weeding and harvesting at just the right time. It's useful to have neighbors who will tell you what grows well in the neighborhood, and where to buy plants and fertilizers. After that, most amateur gardeners are good to go, once they buy a gardening how-to book. Long ago, one other way to improve your garden was to send some daughters to Shipley School, which always dominated the prizes at the Philadelphia Flower Show. However, Shipley has since gone co-ed, and there may have been many other changes.

So, being retired makes gardening possible for people who like it well enough, but never found time at the right season. It's one of the reasons to be reluctant to sell your house which is now too big for you when you retire. Now, at last, you can get things mulched and composted and planted and fertilized and pruned. Especially pruning. There is a tendency in suburban living to plant a lot of bushes and groundcover, and then forget them for twenty years. After a while, the house disappears in the bushes and the whole place looks as though it had been abandoned. It can take two years of pruning and fertilizing to get the place salable; and when you get it salable, you start to lose your interest in selling it. You begin to suspect your neighbors have been prodded into competitive gardening; mustn't let them show you up. Real estate agents who have become unexpectedly friendly tell you neighborhood house prices are holding up nicely. Not now, go away.

|

| Gladiolus |

A few miles further out from suburbia, in exurbia, notice that farmers seldom bother much with landscaping and flower gardening. A former patient of mine once plowed up half an acre and planted gladioli. And then he sold the cut gladioli to a local florist. Houses in the suburbs have foundation planting, azalea usually and rhodedendron right next to the house. Farmers may have just as nice a masonry house, but the lawn grows right up to the foundation wall of the house. Sometimes there is a flowering shrub standing lonesome on the property, usually not even that. If you spend all day every day in the agriculture business, you lose your interest in flower gardens as a hobby. But notice where that has never been true, in Tidewater Virginia and the rest of the deep South. It's not politically correct to say so, but slavery had its advantages for the owners. Once you go beyond having foundation plantings and a kitchen garden, you probably have to have some hired help to garden in a notable way. It's been a help to have power mowers and clippers, fertilizer spreaders and underground sprinkling systems; they just about balance out the loss of gardening assistance from working wives, and the extra time spent commuting extra miles. If a property has been neglected for decades, it's almost a necessity to hire professional help for one or two years to get it into shape. After the work is reduced to maintenance and tinkering, one retired person can handle it with pleasure. If you have kind friends and neighbors, you will learn from them about the choicer seed and plant catalogs, especially those who deliver their plants at just the right time in the season.

Some people prefer vegetables and spices. Tomatoes are a favorite place to begin, and cucumbers. Woodruff is nice as a ground cover and turns cheap white wine into May wine. Scallions and basil are nice. But if you are really serious about vegetables you will elevate the beds a foot above the ground, and it starts to look a little tacky. A compost heap, on the other hand, is unobtrusive and can be made quite elegant. One neighbor boasted he was going to hold cocktail parties in his compost heap.

|

| John Bartram's farm and garden |

Given the chance, it's worthwhile to tour the various show gardens and arboretums in the Philadelphia neighborhoods. John Bartram's farm and garden is right in the center of the city, the way it always has been for the last three hundred years. Bartram hiked all over colonial America, collecting strange plants and flowers for resale. But most of his business was not in Philadelphia or even in America, it was in England. He had a close friend, Peter Collison, who acted as marketing agent if not business partner in Great Britain, where gardening became a major occupation of the great landed estates that American tourists now take such trouble to visit. Obviously, quite obviously, it takes staff to keep such places up. Retirement communities can do the same in a communal way if they could only get themselves pulled together.

|

| Farming |

The subject of tomatoes is a sad one for the Garden State. Because of its sandy soil, southern New Jersey is especially favorable for tomatoes, and cranberries, and peas and beans. New Jersey was once a great truck farm state. Fifty years ago, Campbell Soup would bring in vast heaps of tomatoes to the soup factory in Camden, and they were very good tomatoes indeed. The tomato plants would boom continuously all summer, and vast hordes of tomato pickers would continuously harvest the crop until the first hard frost. However, a new breed of tomato plant was developed, which bloomed and ripened all at once. That was very suitable for mechanical tomato-pickers to harvest, human pickers were no longer needed to tell ripe ones from green ones. So the tomato industry picked up and moved to California, where they can grow three crops a year, harvest them with machines, and improve the bottom line for Campbell Soup. Cranberries went the other way, into the pine barrens, and one family the Haines organized a farmers cooperative called Ocean Spray which bought up almost all of the suitable bogs. Even the Journal of the American Medical Association will attest to the merit of cranberry juice for kidney infections, to the point where it has become a little hard to find cranberries in berry form for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Further south in New Jersey, the canneries organized the local farmers into growing a lot of one kind of vegetable for canning purposes. In the 1920s, however, one Frank Birdseye learned about the value of quick freezing from the Esquimos, and after applying it first to frozen fish, extended it into the various vegetables formerly organized around canning companies. You can now drive for miles past vegetable farms, without seeing a farmhouse. Quakers catch on quick; the same is true in Chester County, Pennsylvania, where the Brock family holds sway.

REFERENCES

| The Pine Barrens: John McPhee: ISBN-13: 978-0374514426 | Amazon |

Gardens for Posterity

|

| J. B. Garden |

We must be indebted to "Several Anonymous Philadelphians" who wrote a book published in 1956 called Philadelphia Scrapple, now out of print but subtitled "Whimsical Bits Anent Eccentricities and the City's Oddities." The Athenaeum librarian has carefully penciled in the names of Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Mrs. Henry Cadwalader as the probable authors of this work, and it's likely that is the fact of it.

Chapter XIV of "Philadelphia Scrapple" discusses a class of notable public gardens not designed to be show gardens, but originally the hobbies or passions of the original owner for private enjoyment, and later were opened to the public. These abound in Philadelphia, sometimes somewhat decayed, often truncated as the land was sold off, but constantly increasing in interest as the boxwood, trees, and shrubs continue to grow in size and rarity. The Anonymous Philadelphians have classed these lovely and somewhat unknown places as "Gardens for Posterity". Quite often, the estate houses to which they belong are better known than their gardens, and the original owners just regarded their gardens as a normal part of the house.

While there are dozens of such places, the more notable ones are Grumblethorpe in Germantown, The Grange in Delaware County, Andalusia along the Delaware, and two famous gardens in decrepit neighborhoods along the lower Schuylkill, John Bartram's Gardens and William Hamilton's ("Woodlands"). There is a record that the Continental Congress once adjourned to visit Bartram's garden, and Hamilton's garden is mentioned by several famous Revolutionary figures since it was on what was then the main route from Philadelphia to the Southern Colonies. John Wister's 1744 garden at Grumblethorpe was 188 by 450 feet in size; some of the boxwood have had a long time to grow.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

To these should be added the hospital gardens at the Pennsylvania Hospital, at Friends Hospital along Roosevelt Boulevard, and the garden of Chester-Crozier Hospital, all of which are especially spectacular in early May when the Azaleas are in bloom. Just about every surviving mansion of colonial rich folks had such a garden at one time.

And tucked away behind many current mansions are lovely gardens that are considered to be just as private as their living rooms. While they are proudly displayed to friends, strangers knocking at the garden door would be considered the height of rudeness. It will take another generation or so for them to be thrown open to the public. By that time, who knows what state of repair they will be in.

For a unified access point for 30 gardens in the Philadelphia area, try www.greaterphiladelphiagardens.org

Haddonfield Blooming Outdoors, Year-Round

|

| Haddonfield Christmas Lights |

DECEMBER. The last of the outdoor blooms disappear at Thanksgiving. The last fall-blooming (Sasanqua) camellias, witch hazels and surviving rose bushes finish up, and the glorious maple trees have lost their fall foliage. In a warm year, the lawns remain green through Christmas, while the town lights up its trees and shrubs, and doorways, and lamp posts. The church carillon plays carols; it gets dark early. Old timers tell you of once riding to Moorestown for Christmas in a one-horse open sleigh. Winters are definitely getting warmer, but it's unclear whether this has to do with global warming or just hot water from a million drain-pipes warming up the rivers. The Philadelphia water department reports it extracts seven times as much water from the river as flows past from Torresdale to Marcus Hook. Each drop must go through seven sewage systems during that transit. Warmer weather or not, one gets to wishing the home oil delivery services would post their prices on big signs, the way gas stations do. Price controls are abhorrent, but sometimes the competitive marketplace could use a little help.

|

| Holly Berries |

JANUARY'S Ice and snow, as sung by Flanders and Swann, make the nose and fingers glow. There's not much blooming outdoors along the Atlantic coast north of Cape Hatteras in January, although the holly berries are still colorful, especially when surrounded by a thin dusting of snow. There is at least one Haddonfield family, the Coffins, who make a hobby of growing a wide variety of holly variants, many of them quite hard to grow. For some semblance of outdoor color in January, however, red berries on a tall bush show up best.

In my family, we also resort to Christmas cactus for flowers at this time of the year. It's a house plant, however, and it's a succulent, not a true cactus. In spite of the name, it only reliably blooms at Christmas if you force it to. Our formula is to stop watering it at Hallow E'en and resume watering at Thanksgiving, keeping the plant in semi-darkness during that period. Even so, it's more naturally a January bloomer, and among the easiest indoor plants to maintain. Our Christmas cactus plant is in its fourth generation within our family, with three living generations maintaining descendants of the original plant. Grandma's Christmas cactus is a living link within the family, helping us to remember who we are.

|

| Early Sprouts |

FEBRUARY'S slush and sleet, sing the Englishmen, freeze the toes right off your feet. Toward the end of the month in one of Haddonfield's milder winters, you can expect the snowdrops to flower around the base of dormant dogwood trees. These bulb plants are not very showy except for being the only thing in bloom, so plant a lot of them in clusters in the early fall, using loose soil so they can naturalize. Generally speaking, rabbits leave them alone, and in a week or so they are joined by Snowdrops, Glory of the Snow, and FSquill. The leaf fall from dogwood trees from is so dense you probably find bare ground around the base of the tree; needs something to brighten it up. The red holly berries are still on the bush; if you are lucky you have varieties of holly with white stripes on the leaves, although variegated plants are less hardy than the plain green ones. During a mild snap, daffodils poke up spikes of leaves, and a few of them have tinges of yellow. Haddonfield can get a ton of snow in February, but not every year. Some years are so mild they snatch away all the fun from neighbors who take cruises or go to southern climes for an unnatural suntan, but older residents can remember years when the Delaware River froze over. The early blooming magnolias are in bud, offering promise of what is to come. Almost everyone's lawn is a dormant brown.

|

| Snowdrops |

MARCH arrived like a lamb this year, not every year. After a late 5" snowfall melted, the snowdrops carpeted the beds under the dogwood trees. The snowdrop idea is spreading; several neighbors have clumps of them. Plant them in clusters, not strings; in loose soil, they naturalize freely. Daylight savings time arrived, making a lot of people late for church, but helping to give the feeling of spring, which isn't officially here until March 21. The daffodils are up, showing tips of yellow. Magnolias are in bud, the grass is brown, but peppered with shoots of Star of Bethlehem. The star plants are nice but thrive in muddy areas to the point they seem like weeds. As bulb plants, Star of Bethlehem come up in the spring looking like rich green early grass. Since no chemicals seem to affect them, the best you can do is mow the fresh-looking "grass" as early and as close as you can; it retards them, maybe making them die out. If you let them bloom and go to seed, you are lost. Star of Bethlehem dries up and dies on the first really warm day, leaving a bare patch in the lawn, which crabgrass is happy to fill up. March 12: Crocus, out of nowhere, blooming profusely before the daffodils make the leap. The first year you plant bulbs, they come up slowly; in years after that, they seem to jump out of the ground. Planting a few new ones every year is a way to extend the season. Sooner or later the crocus will die out; better to stick with snowdrops and squill, which will usually naturalize. By the end of March, the crocuses are fully out, the Glory of the Snow is truly glorious, the squill abundantly naturalizing in the lawn. are suddenly in full bloom because the buds are hidden under the leaves until the flowers push forward. Hellebore gets better every year, filling up shady places and somehow repellent to rodents and deer. The opposite is true of hyacinths, which get a great start but are quickly eaten by rabbits attracted by the nice odor. Forsythia are starting to blossom, sort of straggly if wild, but brilliant yellow if . Lots and lots of buds are appearing on the bushes.

|

| Forsythia |

April Fool's day really starts the main season for Haddonfield blooming. The most striking announcement that Haddonfield is ready to go comes from the magnolia trees, because they are thirty or forty feet high, completely covered with bloom. Depending on the rainfall, and whether you fertilized adequately, the lawns are now green. Most people start mowing their lawns a week or so too late, leaving the brown stubs of last year's grass showing, and allowing the confounded Star of Bethlehem to get a start. Back down at ground level, the clumps of Glory of the Snow and Squill make a very welcome show at this time of year, but the Snowdrops are pretty well over. If you are doing this sort of small-bulb edging, it's best to mix all three in the same bed to extend the small-bulb season. Flowering quince trees (or bushes, really) come out on April Fool's day, but they are easily nipped by a cold snap, and revived by warm weather. In some years when the temperature hovers around the freezing point, it is possible to have three different bloomings of flowering quince, extending over several weeks. The Hellebore stays in bloom for several weeks in April, although the foliage grows up and hides the blossoms. If you plant magic lily among the Hellebore, the leaf fronds will mix among them and then die down; the tall lily blossoms appear "like magic" in August. Daffodils are in abundance at this time, in case Wordsworth is watching, making a ground-level yellow display underneath the yellow forsythia, also in full bloom. Blooming at the same time are the mucronulatum azaleas, which are really rhodedendrons, showing a nice lavender color. Like the forsythia, the wild types are rather scrawny and sparse, while the hybrids have thickly blossomed with a brighter hue. Eat your heart out, neighbors; with these early bloomers we can have a showy spring display a month earlier, at a time when you are hungry for spring color. Notice there are four common plantings which are broad-leafed but retain their leaves all winter. Evergreens with needles, of course, but in addition the Korean dogwood is green all winter, the magnolias have shiny leaves year-round, and the scuba. Acuba are a very worthwhile addition to any garden, because they flourish in shade and sun, are simple to transplant just from sticking bare shoots in the ground, and quickly hide garbage cans, garage entrances, etc. They have a spectacular red berry hidden under the top leaves; trim them down six inches and you will see bright red berries from December to May. They aren't blossoms but are just as colorful. Some people plant crocus and hyacynths for this season, but my advice is they are just too attractive for rabbits when you can fill the same space with daffodils and Glory of the Snow. Tulips? Well, they have to be dug up every year and replanted, and then the dead blossoms have to be trimmed after they bloom; too much trouble for me. Lilacs? Well T.S. Eliot made them famous in the Waste Land but they require alkaline soil to thrive; Haddonfield soil is naturally too acid for lilacs unless you keep putting lime on them. If you come to Haddonfield and stay for years (why not?) you concentrate on things that are low-maintenance. People who move into town from Michigan are forever planting lilac, crocus, and tulips, but that's high-maintenance in Haddonfield.

|

| Azalea |

April 7: The parade of colors is beginning. Flowering fruit trees, flowering apple trees, cherries are in abundance throughout southern New Jersey. In center city Philadelphia, someone had the splendid idea of planting Ginkgo trees along the sidewalks. They look pretty much like flowering apple trees but require very little water so they become the urban favorite. When you plant flowering trees, it may take ten or more years before you see what the effect is, especially how the color fits in with the surroundings; and by then it is too late. Latecomers to the garden competition have a better chance to alternate a contrasting color. When there's nothing else in bloom, white is pretty spectacular. But when every tree is the same, it can be a little boring. For example, this is cherry blossom time in Japan, but the Japanese have so over-planted pink cherry trees for the season that although overwhelming at first, eventually the universal pinkness is pretty boring indeed. Meanwhile, all of the deciduous trees are starting to leaf out, but haven't reached the point of identifiable leaves. In many ways, this is the most beautiful brief season of the year, as every tree shows lacy tracery against the sky, but only for a few hours before the leaves appear.

April 16: The pachysandra ground cover is covered with clusters of little white flowers, which usually last for less than a week. It's hard to justify planting them for that, but important to remember an old maxim: That which grows on bare ground under a Norway maple is pachysandra -- maybe. For this purpose, Haddonfield used to have a great deal of Periwinkle, whose bright blue flowers seem somewhat more persistent because they do not all come into bloom at once. Periwinkle takes a fair amount of care, however, particularly to rake the Maple leaves away in the Fall without uprooting the ground cover, water in the summer, fertilize in the Fall; so it's falling off in popularity. If you like little blue flowers that are easier to manage, try Forget-me-nots, which come into bloom at the end of April and persist for a couple of weeks. This the magic time in South Jersey, where all the trees seem lacy with early leaf, and the laziness is echoed by Japanese cherry trees, star magnolia, and forsythia; it's a pity this wonderful moment only lasts a few days. The grass is generally green, but still growing slowly.

|

| Pink Dogwood |

MAY is heavenly in Haddonfield. Three main acid-loving plants dominate the scene: azalea, dogwood

Little blue blossoms as a ground cover are another garden feature which can give the appearance of an extended season. The glory of the Snow is planted as bulbs in the fall, coming up just as the snowdrops fade away. And then the little blue flowers of periwinkle take over as a ground cover when the forsythia is out, followed by Forget-Me-Nots during the azalea season. Grape hyacinth fit in here, too. Bulbs, ground covers, and perennials are very different sorts of plants, but the low-growing little blue flowers are much the same at a distance and can give the appearance of almost two months of continuous garden effect. Along with lily of the valley, which has a sweet fragrance, it is possible to replace the bare-earth appearance of a landscaper's commercial flowerbed with a display that is fun to watch in its subtle variations -- almost all spring long. Don't forget a patch of Woodruff, which makes a nice ground cover like pachysandra, with the bonus that a few blossoms floating in a bottle of cheap white wine convert it into delightful May Wine, Haddonfield style.

If you drive around Haddonfield in the spring, you can come across occasional homeowners who have gone too far with azaleas. They probably didn't realize what they were doing when they installed far too many azaleas of different color and habit as small plantings. But after twenty years, these bushes will grow pretty big and shaggy, looking especially overdone when one house is like this, but all the neighbors have nothing but green yards. This problem can be addressed by removing a few of the biggest bushes, and less appropriately, by trimming them like hedges. Overdone gardens like this need to be pruned, and rather severely. The best time to do it is just after the blooming has stopped, which is also the time when the recollection of kitchiness is most acute. These people mean well, so be kind to them.

May 15. The trees are almost completely leafed out, and the grass is lush green. It's easy to be fooled by the grass, which can contain a lot of annual bluegrass and clipped-off Star of Bethlehem which will die off on the first really warm day, usually in June, leaving bare spots. What you need is perennial bluegrass, preferably of several varieties to resist diseases. Matching the full leaf-out of the trees are the hybrid rhododendrons, which are essentially the same as azaleas but taller and somewhat showier. They are less hardy than other rhododendrons; sometimes six or seven of them will be killed by a sudden cold snap, ruining your garden effect; so don't depend on them exclusively. Wegelia is out now, with nice effect, too.

Memorial Day used to be the last day of May, but to create three-day weekends, it now varies in timing by several days. In some regions, it's traditional to look for peonies, all crawling with ants, on Memorial Day, but in Haddonfield, it's the time for Mountain Laurel to be in full bloom. It takes ten to fifty years to produce an effective laurel bush out of a puny little potted plant, but when you do grow one, it makes a pretty spectacular Memorial Day. Laurel is the state flower of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, but it seems less popular as a garden plant than it once was. There's also the mean rumor that honey from laurel blossoms is poisonous, but it's hard to get scientific verification of that. So many wildflowers are in bloom in late Spring, it seems relevant that the documented episodes of poisoning mostly date from the Civil War when both Northern and Southern armies were foraging in the North and South Carolina mountain wilderness. Belladonna would easily explain the symptoms the soldiers reported. There's still a Memorial Day parade in Haddonfield on Memorial Day, now much smaller than the one on the Fourth of July, although fifty years ago it was the other way around. Very likely, the Civil War veterans died off and World War I veterans favored Armistice Day. The American Legion, now mostly World War II veterans, has taken up Memorial Day, while the Veterans of Foreign Wars (originally Spanish American War, now Vietnam veterans) seem to like Independence Day. It does seem we have too many wars because it's possible to think of several others that haven't even adopted a parade.

JUNE in Haddonfield is usually a month with two seasons, late spring and early summer. At the start of the month, the left-overs from late May are still blooming, but winding down. The Mountain Laurel and hybrid rhododendrons start the month in full bloom, and then gradually fade out by about the tenth of June. Sweet magnolias come out then, with rather amazingly big flower buds. There are Easter lilies, and roses in great abundance. Astilbe in several colors is at the base of the larger bushes, and the lawns are still richly green, even bluish tinted. There are bunnies running around aimlessly, and squirrels seriously pursuing their tasks; comparatively few birds are on the ground, but up in the trees there is a great abundance of songbirds, especially early in the morning. They better watch out, a neighbor reports nesting hawks, and those owls are somewhere around.

June 15. The early June blooms are fading, but some straggler azaleas and hybrid rhododendrons persist, especially in shady areas. But the middle of June is the time for the hydrangea to pop out, and if you have taken care, there will be several interesting varieties in several colors. The Korean dogwood is just starting to blossom, about the time you gave up and assumed they never would. The blossoms (corms) start out tinted green and then turn white as they grow in size, and for some reasons, the tree will blossom in some areas well before others. This tree looks deciduous, but in Haddonfield at least the leaves remain green on the trees all winter long. And now, the wild rhododendron starts to blossom, continuing up to about the Fourth of July. These bushes are big, and they bloom abundantly, but the blossoms tend to be deep within the foliage, bloom sequentially instead of all at once, and are thus much less showy than the hybrids. But if they have been planted near the outside of a window, the blossoms are quite nice when viewed from inside the house. Sort of house plants, growing outside. Be aware of a sudden burst of hot weather. The Star of Bethlehem will suddenly grow brown, and the annual bluegrass will die as well. his is the moment in the season when a good lawn suddenly looks second-rate, but a really really good lawn just shows 'em all up. Merion bluegrass; there's nothing like it.

|

| Independence Day |

JULY'S first week revolves around the celebration of Independence Day, and in Haddonfield that means the Parade. Since the Declaration was ratified and the State of New Jersey was then immediately founded in the Indian King Tavern, the excitement is natural enough. There are fireworks and antique cars, string bands and bagpipers, service clubs and neighborhood displays, but any old-timer will tell you the central excitement of the parade and the memories generated, focus on the little kids with decorated bicycles. As far as flowers are concerned, the main display is the wild rhododendrons, with daylilies starting up, and hydrangea of many colors. There are a few Southern Magnolias, especially one in front of the Episcopal Church, with flowers as big as dinner plates, but most of these flowering trees have been planted fairly recently so the blooms are sparse. Give them a few good growing seasons before they make an impact on the town. By mid-July, most of the color is coming from window boxes and perennials along the borders of the lawns. Here's one thought about nature in the summer: Although the dominant front-yard color in Haddonfield in July and August is green (the flowering annuals and perennials are mostly in the back yards), there is the question of insects and birds. The buddleia plant attracts butterflies and hummingbirds, honeybees are attracted by the flowers of Hosta, and phlox attracts lots of bumblebees. We're in the migratory path for birds, so there are spring and fall migrants; nesting birds predominate in hot weather, so that's what should be attracted to bird feeders with sunflower seeds. It isn't unusual for a house to have eight or ten bird feeders, where the main problem is squirrels, lots and lots of squirrels. Chipmunks and squirrels are fun to watch, just like hummingbirds and bumblebees, but you should give some thought to what kind of ecosystem you hope to promote.

|

| Crape Myrtle |

AUGUST in Haddonfield features Crape Myrtle, which comes in many shades of red, and many sizes from three-foot bushes to thirty-foot trees. They are a southern flowering bush, just barely hardy this far North, so it pays to shelter them a little when you plant them. For the most part, blooming flowers in Haddonfield are mostly found in the back yards during August. The annuals are too numerous to mention, so an experienced gardener groups color schemes. Another trick is to plant seven-foot sunflowers in the back, five-foot gladioli in front of them, and three-foot phlox in front of that. Let's not forget to mention crabgrass. When the ground is wet they are relatively easy to pull up, when they get to be twelve-inch mounds they are almost impossible to pull. Newcomers are pleased crabgrass is such a quick-growing thick green turf, but they are the enemy and don't you forget it. They are an annual, so the first frost turns them brown, and they seed themselves relentlessly. Part of enjoying a garden is learning to enjoy pulling up crabgrass.

|

| sunflowers |

SEPTEMBER, remember, as the mariners say about hurricanes. Somewhere it is written that 80% of the rainfall along the Atlantic coast in the autumn is caused by coastal storms, sometimes hurricanes, sometimes nor'easters, sometimes just storms. Variability of the rainfall in autumn is one of the main causes of variability in spring gardens. Since September is the perfect time to put in new grass seed, the quality of lawns has a lot to do with coastal storms the year before. It's almost three months since the days started getting shorter on June 21, so the flowering plants are starting to fade. Crape myrtle is good for the first two weeks, and spider plant gets three or four feet tall, an annual that looks like a flowering bush. The August blooms, of sunflowers and phlox, are starting to droop a little. It's definitely time to go to the local plant store and get a dozen or so chrysanthemum plants. Yes, it's possible to debut them in the summer, prune them into tight bushes, and have a perennial that comes back every year. But you have to be a slave to chrysanthemums all spring and summer in order to have anything as full and compact as you can buy at the store. There are lots of 'mums in Haddonfield all fall, but almost all of them are purchased in pots in September.

September is the critical moment for good lawns. Permanent lawns go dormant around the end of August, and even the best of them look a little shaggy then. The most neglected lawns die at this time, for lack of water, fertilizer, excess heat, and so on. However, permanent lawns with lots of bluegrass will respond to this weather signal by thickening up, one shoot dividing into three or four, and after a week or ten days will produce the best lawn of the year. Now is the time to fertilize, now is the time to reseed bare patches; every few years it may be time to thatch and thin out, although the lawn will look terrible for a month after hatching. If you seed, mainly use bluegrass plus a little fescue for shady areas. When reading the box of seed, just ignore the ryegrass, even if it says "permanent" ryegrass. Treat ryegrass as just so much sand diluting the good grasses; only use it if you are planning a quick sale of your house and want it to look nice for a few months. The secret of a good lawn is fertilizer, but of course, you can't grow wheat if you plant corn, you must give it some good seed worth fertilizing.

|

| Fall Leaves |

OCTOBER, according to the New England college drinking songs, is when the leaves do fall, so early in October. However, those who prefer the advantages of living in Haddonfield have the additional advantage of finding that in Haddonfield, the leaves turn brilliant and start to fall, so late in October. The rest of the color in October is left-over from the September fall revival. Lots of colored leaves lead to lots of leaves on the ground to rake. And you better rake them off the lawn, too, or else they will rot and kill the grass, leading to bare ground, which washes away from the tree roots and looks just terrible. So rake, and rake cheerfully. Blessings on the Borough, which sends trucks around to suck them up into trucks and takes them away, so they don't clog up the storm sewers with disheartening floods in the streets when it rains, as it frequently does when fall hurricanes sent storms up our way. Remember, do your share of leaf raking, and do it both quickly and cheerfully.

|

| Chrysanthemum |

NOVEMBER has some late-blooming flowers, especially chrysanthemums and others of what Linnaeus called the Aster family, but which DNA studies show are just late-blooming flowers that sort of look like chrysanthemums. We're not going to get into this argument since the use of DNA typing seems to lead to placing the typical florist's chrysanthemum outside the chrysanthemum family, and endless other confusion which would serve this website no particular good until it settles down in forty or fifty years. A few stragglers like the spider plant will continue to bloom into November unless there's an early frost, along with "Asters" and dahlias, but all of that is a lot of trouble for a suburban landscape after school has begun, and the leaves are piling up, taking time to rake during short daylight hours. Be content with the glorious colors of the many maple trees, especially those lining the long straight streets like golden arches. We don't have much red color in the maples, such as you see in Vermont, so it's a good idea to plant some Euonymus bushes which will soon grow into trees and have stunning scarlet leaves in early November. The one really good fall-blooming shrub is the fall Carmelia, which comes in a variety of colors, but the white shows up best in my opinion. Camellias, whether of the fall-blooming or Japonica variety, are truly best suited to more southern climates. However, if you can find a place that is both sunny and protected -- a difficult combination to find -- they can grow to a height of six or eight feet, covered with blossoms at a time when foundation shrubbery is ordinarily pretty drab. After ten or fifteen years you can expect an early frost finally to get them, so don't be disheartened if that happens, just start over. If you have the sort of employer who transfers people every two years, just stick with pots of florists' chrysanthemums.

|

| The glory of the Snow |

|

| Spring Budding |

|

| Spring Budding |

|

| Daffodils |

|

| Crocus |

|

| Japanese Cherry |

|

| Grape Hyacinth |

|

| Narcissus |

|

| Azalea |

|

| Wisteria |

|

| Lily of Valley |

|

| Magnolia |

|

| Money Bush |

|

| Forget Me Nots |

|

| Tezou |

Harriton House

|

| Harriton House |

Three hundred years ago, in 1704, Roland Ellis acquired 700 acres of the Welsh Barony in what is commonly called Philadelphia Main Line and built a palatial house on it. He called his homestead Bryn Mawr, or great hill, after his ancestral home in Wales of the same name, thereby explaining why Bryn Mawr College and Bryn Mawr town have the name but are not notably situated on hills. The town of Bryn Mawr was once called Humphryville. But Bryn Mawr sounded nicer, even though there are plenty of Humphries still around to defend the older designation.

About fifty thousand acres were set aside by William Penn as the Welsh Barony, and there was the willingness to allow it to be self-governing, although that didn't much happens because the inhabitants saw no point in being self-governing. Nevertheless, the term isn't just an ethnic allusion, but has some historic meaning.

In any event, Ellis proved to be an unsuccessful manager of his estate, which rather soon passed into the hands of the Harrison family, who lived on it for about two hundred years until real estate development, and the taxes related thereunto, forced the creation of a complicated arrangement, with the township of Lower Merion owning the property and a non-profit group called the Harriton Association managing it. They have luckily obtained the services of a famous curator, Bruce Gill, who does research, writes papers, and organizes programs for visitors. The neighbors in the area, all living on land that formerly belonged to the Harrisons, are said to constitute the richest neighborhood in America. By building the original farmhouse rather far from the main road (Old Gulph) and remaining surrounded by neighbors who want to have privacy, Harriton House has fewer visitors than it deserves because it is so devilish hard to find.

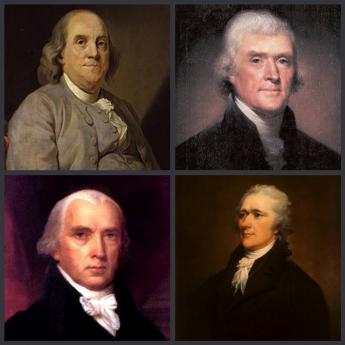

There was a little local skirmishing during the Revolutionary War, but the main historical significance of the House was that Charles Thomson married a Harrison and lived there all throughout the period of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation (1774-1789) as the Secretary of the Continental Congress. His little writing desk is, therefore, the most notable piece of furniture at Harriton House since every piece of official paper involved in the whole Revolutionary episode passed through it or over it. Modern organizations would do well to notice that Thomson was not given a vote and was expected to be totally unbiased about Congressional affairs. Even in those days, there must have been cautionary experience with secretaries who tinkered with the minutes for their own preferences. It certainly was entirely fitting that this last steward of the Articles of Confederation was designated to carry the news to George Washington at Mount Vernon, that he had been elected President of the new form of government. No doubt, Washington was pleased but unsurprised to learn of it.

While Harriton House is imposing on the exterior, and was the likely prototype of many characteristic Main Line stone mansions, the inside of the house is quite primitive. In those days it was cheap to build a big house but expensive to heat it. In 1704 surrounded by a continent of a forest, firewood may not have seemed a problem, but it quickly posed a transportation problem, and later houses tended to shrink in size. In any event, the interior of the house seems strangely bleak and bare, quite in keeping with the early Quaker principle of building a structure "without paint, or other adornments". Bruce Gill spent quite a lot of time and effort to determine that the random-width flooring had never received any shellac, varnish or wax. Those are beautiful floors, but the "finish" is just three hundred years of oxidized dirt.

The original Bryn Mawr, now called Harriton House, is well worth a visit. If you can find it; GPS is the modern solution.

Highway Beautification

|

| Prince Grigory Potemkin |

Someone who has traveled in modern China -- and is at all observant -- knows that the extensive slums and trashy wastelands of the Inner Kingdom are systematically hidden from tourist's eyes by fences and plantings of tall trees. In a few years, the trees will grow a few feet taller and fully conceal what is behind them, but today modern tourist buses are high enough so you can see over the treetops if you look. When American tourists notice this, they are very smug.

The term Potemkin Village is a somewhat exaggerated term for the process Grigory Potemkin used to clean up the villages that his girlfriend Catherine the Great passed through on her visit to southern Russia and Crimea. He apparently did not construct whole fake villages as enemies claimed, but he was unnecessarily forceful,

|

| West Philadelphia, at one time. |

let us say, in his efforts to smarten things up. After taking a few rides on Philadelphia's suburban commuter trains, or a boat ride up to its rivers, the idea does cross most minds that we could use a Potemkin in charge of our Streets Department, or maybe a Communist Chinese on loan. We have miles, maybe even hundreds of miles, of overgrown weeds along our embankments, spiced with the discarded trash of historic duration. Since nobody wanted to live next to coal-burning locomotives, and most people even dislike the noisy though cleaner replacements, the houses along the railroad clearly deserve to be hidden. That's true in almost every town in the world (not Japan, not Switzerland) and it's deplorably true in our Philadelphia. Seaports and riverbanks are a mess everywhere, too, and we are certainly in style in that department as well. Why can't the Schuylkill look like the Seine, next to the cathedral of Notre Dame?

So the Chinese have combined the concept of cleaning up their public spaces, which we applaud, with the concept of hiding the economic truth, which we sneer at. Maybe we should give some thought to a spin campaign, the essence of which is a metropolitan crusade to pick up the trash, build some strategic fences, and plant a whole lot of tall evergreens along with the public ways. We've made a good start with Boathouse Row; why not extend it to Gray's Ferry, or even to Norristown? The idea is not a new one; Lady Bird Johnson made it her main goal in public life.

In 1965, Lyndon Johnson used his famous powers of legislative persuasion to give his wife what she wanted. The Highway Beautification Law of 1965 was passed by Congress on Lady Bird's birthday, with everyone in the gallery dressed in evening clothes. With the vote counted and enormous standing applause registered for fifteen minutes, the whole group traveled over to the White House for a signing of the law with nineteen pens. There followed the birthday party at the White House, to end all birthday parties. Highway billboards were a thing of the past.

That was forty or so years ago, and unfortunately, the billboard companies didn't like it at all. Through administrations both Democrat and Republican, the Department of Transportation has never issued regulations, so Highway Beautification was never implemented. It represents just one more unwritten aspect of the Constitution that James Madison and his friends didn't fully anticipate.

Laurel Hill

|

| Laurel Hill Cemeteries |

There are two Laurel Hill Cemeteries in Philadelphia, sort of. Although both are described as garden cemeteries, the older part in East Fairmount Park is more of a statuary cemetery or even a mausoleum cemetery. When its 74 acres filled up, the owners bought expansion land in Bala Cynwyd, which could come closer to present ideas of a memorial garden. Particularly so, when the older cemetery area started to fill in every available corner and patch and began to look overcrowded. The name was used by the Sims family for their estate on the original area. Since June-blooming mountain laurel is the Pennsylvania state flower and a vigorous grower, it seems likely the bluff overlooking the Schuylkill was once covered with it. Somehow the May-blooming azalea has become more popular throughout the region, particularly in the gardens at the foot of the Art Museum. If extended a little, merged with laurel on the bluff, and possibly with July-blooming wild rhododendron, there might someday arise quite a notable display of acid-loving flowering bushes from the Art Museum to the Wissahickon, continuously for two or three months each spring.

There are interesting transformations in the evolving history of cemeteries, best illustrated in our city by the traditions of the early Quakers when they dominated Philadelphia.

|

| Thomas Grey |

Objecting to the ornate monuments which Popes and Emperors erected for their military glory, and probably to the aristocratic custom of burying important people inside churches where they could be worshiped along with the stained-glass saints, early Quakers were reluctant to mark their own graves with headstones, or even to have their names engraved on such "markers". By contrast with the splendor accorded aristocrats, the common people in Europe were largely dumped and forgotten, providing an unfortunate contrast. During the early part of what we call the romantic period, Thomas Gray popularized these attitudes in Elegy in a Country Churchyard. To be fair about it, the early Christian Church had a strong tradition of collecting the dead of all classes into catacombs. The Romans were quite reasonably upset by the potential for spreading epidemics through people living within such arrangements, although feeding the Christians to the lions seems like an overreaction.

At any rate, and to whatever degree the French Revolution was what shattered previous traditions, the Victorian or romantic period produced a new vision: garden cemeteries in Paris.

|

| George Mead |

The concept soon spread to Laurel Hill, and thence to the rest of America. Acting with what probably had some commercial motivation, cemeteries then moved away from churches to suburban parks, promoted as places of great beauty in which to stroll and hold picnics, perhaps to meditate. The private expense was not spared in statues and mausoleums, which often became display competitions between dry goods merchants and locomotive builders. Revolutionary heroes were dug up from their original graves and transported here to be more properly honored, as were some private persons whose descendants wished for more suitable recognition than conservative church rectors had offered. The Civil War created the staggering number of 632,000 war dead; based on the proportion of the population, that would be equivalent to six million in today's terms. Since they were almost all male, there must have been at least a half-million surplus women as a consequence. The nation and this almost unbelievably large cohort of single women had an impact on society for thirty or forty years after The War. Eventually, this would lead to colleges for women, suffrage and other forms of feminism, but the initial manifestations of what we now call Victorianism took the form of formalized grief, particularly the 75 National Cemeteries of crosses row on row. But private initiatives also took a variety of forms, including Laurel Hill's statuary to honor the valor of the fallen, ranked by the number of generals buried there and visits by sitting Presidents of the United States. Laurel Hill, East, holds 42 Civil War Generals. It will be recalled that Lincoln's Gettysburg Address was delivered at a much larger final resting place for fallen soldiers, but Laurel Hill had the generals, including George Gordon Meade, himself. It is probably significant that Laurel Hill West, three times as large, was opened in 1867. At the headstone of each Civil War veteran is found a metal flag-holder, put there by the Grand Army of the Republic and marked with GAR surrounding the number 1. This is the home of Post Number One, the Meade Post, the original home of this organization responsible for many patriotic movements like the Pledge of Allegiance and commemorative reunion encampments and reenactments. The main purpose of the war was to preserve the unification of a continental nation, and the GAR sought to raise patriotic consciousness to a point where fragmentation would never again be conceivable.

|

| John Notman |

Two names stand out in the history of these cemeteries, Notman and Bringhurst. John Notman was one of the early architects who fashioned the look and feel of Philadelphia. His identifying feature is brownstone, as seen cladding the Athenaeum building on Washington Square, and St. Marks Episcopal Church at 15th and Locust. At Laurel Hill, the main entrance confronts a brownstone sculpture by Notman of "Old Melancholy", depicting a typical Victorian romantic vision; just about all other monuments in the cemetery are either of acid rain-eroded marble or indelible granite. Brownstone from Hummelstown PA provided the characteristic look of New York residential architecture during this era. Philadelphia brownstone probably came from the same place. The other name is Bringhurst, dating back to 17th Century Germantown, long associated with the underlying sanitary purposes of the cemetery. The family finally and gladly sold the undertaking business a few decades ago.

Somehow, the image of cemeteries has now transformed from public places of meditation and reverence to places that are "spooky". Their greatest surge of visitors, these days, occurs at Halloween.

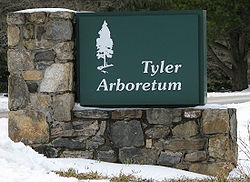

Morris Arboretum

The former estate of John and Lydia Morris is run as a public arboretum, one of the finest in North America.

|

Morris is the commonest Philadelphia name in the Social Register, derived largely from two unrelated Colonial families. In addition to their city mansions, both families had country estates. The country estate once belonging to the Revolutionary banker Robert Morris was Lemon Hill, just next to the Art Museum, where Fairmount Park begins. But way up at the far end of the Park, beyond Chestnut Hill, was Compton, the summer house of John and his sister Lydia Morris. This Morris family had made a fortune in iron and steel manufacture and were firmly Quaker. Both John Morris and his sister were interested in botany and had evidently decided to leave Compton to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a public arboretum. John died first, leaving final decisions to Lydia. As the story is now related, Lydia had a heated discussion with Fiske Kimball, at the end of which the Art Museum deal was off. She turned to her neighbor Thomas Sovereign Gates for advice, and the arboretum is now spoken of as the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania. It is also the official arboretum of the State of Pennsylvania. To be precise, the Morris Arboretum is a free-standing trust administered by the University, with the effect that five trustees provide legal assurance that the property will be managed in a way the Morrises would have wished. In Quaker parlance, Lydia possessed "steely meekness."

A public arboretum is sort of an outdoor museum of trees, bushes, and flowers, with an indirect consequence that many museum visitors take home ideas for their own gardens. Local commercial nurseries tend to learn here what is popular and what grows well in the region, so there emerges an informal collective vision of what is fashionable, scalable, and growable, with the many gardeners in the region interacting in a huge botanical conversation. The Morris Arboretum and two or three others like it go a step further. There are two regions of the world, Anatolia and China-Korea-Japan, with much the same latitude and climate as the East Coast of America. Expeditions have gone back and forth between these regions for a century, transporting novel and particularly hardy or disease-resistant specimens. An especially useful feature is that Japan and parts of Korea were never covered with glaciers, hence have many species found nowhere else in the temperate zone. Hybrids are developed among similar species found on different continents, and variants are found which particularly attract or repel the insects characteristic of each region. The Morris Arboretum is thus at the center of a worldwide mixture of horticulture and stylish outdoor fashion, affecting millions of home gardeners who may never have heard of the place.

Native Habitat

|

| Gifford Pinchot |

Teddy Roosevelt's friend Gifford Pinchot is credited with starting the nature preservation movement. He became a member of the Governor's cabinet in Pennsylvania, so Pennsylvania has long been a leader in the formation of volunteer organizations to help the cause. Sometimes the best approach is to protect the environment, letting natural forces encourage the growth of butterflies and bears in a situation favorable to them. Sometimes the approach preferred has been to pass laws protecting threatened species, like the eagle or the snail darter. Sometimes education is the tool; the more people hear of these things, the more they will be enticed to assist local efforts. The direction that Derek Stedman of Chadds Ford has taken is to help organize the Habitat Resource Network of Southeast Pennsylvania.

|

| butterfly |

The thought process here is indirect and gentle, but sophisticated; one might call it typically Quaker. Volunteers are urged to create a little natural habitat in their own backyards, planting and protecting plant life of the sort found in America before the European migration. If you wait, some insects which particularly favor the antique plants in your garden will make a re-appearance, and in time higher orders like birds that particularly favor those insects, will appear. The process of watching this evolution in your own backyard can be very gratifying. To stimulate such habitats, a process of conferring Natural Habitat certification has been created. In our region, there are over three thousand certified habitats.

Of course, you have to know what you are doing. Provoking people to learn more about natural processes is the whole idea. For example, milkweed. That lowly weed is the source of the only food Monarch butterflies will eat, so if you want butterflies, you want milkweed. For some reason, perhaps this one, the Monarch is repugnant to birds, so Monarchs tend to flourish once you get them started. After which, of course, they have their strange annual migration to a particular mountain in Mexico. Perhaps milkweed has something to do with that.

|

| Empress tree |

If you plant trees and shrubs along the bank of a stream, the shade will cool the water. That attracts certain insects, which attract certain fish. If you want to fish, plant trees. And then we veer off into defending against enemies. The banks of the Schuylkill from Grey's Ferry to the Airport are lined with oriental Empress trees, with quite pretty purple blossoms in the Spring. These trees seem to date from the early 19th Century trade in porcelain (dishes of "China" ) on sailing vessels. The dishes were packed in the discarded husks of the fruit of the Empress tree, and after unpacking, floated down the Schuylkill until some of them sprouted and took root. Empress trees are certainly an improvement over the auto junkyards hidden behind them. On the other hand, Kudzu is an oriental plant that somehow got transported here, and loved what it found in our swamplands. Everywhere you look, from Louisiana to Maine, the shoreline grasslands are a sea of towering Kudzu, green in the spring, yellow in the fall. It may have been an interesting visitor at one time, nowadays it's a noxious weed. So far at least, no animals have developed a taste for Kudzu, and no one has figured out a commercial use for it. When an invasive plant of this sort gets introduced, native habitat and its dependent animal life quickly disappear. So, in this situation, nature preservation takes the form of destroying the invader.

|

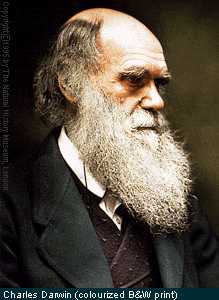

| Charles Darwin |

But where is Charles Darwin in all this? The survival of the fittest would suggest that successful aggressors are generally fitter, so evolution favors the victor. Perhaps swamps are somehow better for being dominated by Kudzu, pollination might be enhanced by killer bees. At first, it might seem so, but if the climate or the environment is destined to be in constantly cycling flux, diversity of species is the characteristic most highly desired. For decades, biologists have puzzled over the surprising speed of adaptation to environmental change. Mutations and minor changes in species seem to be occurring constantly, and most of them are unsuccessful changes. But when ocean currents change, or global warming occurs, or even man-made changes in the environment alter the rules, we hope somewhere a favorable modification of some species has already occurred standing ready to take advantage of the changing environment. Total eradication of species variants, even by other species which are temporarily better adapted, is undesirable. In this view, the preservation of previously successful but now struggling species is a highly worthy project. The meek, so to speak, will someday have their turn, will someday inherit the earth. For a while.

|

| St. Lawrence Seaway map |

And finally, there are variants of the human species to consider. To be completely satisfying, a commitment to preserving "native" species in the face of aggressive new invaders must apply to our own species. Surely, a devotion to preserving little plants and insects against the relentless flux of the environment does not support a doctrine of driving out Mexican and Chinese immigrants at the first sign of their appearance, like those aggressive Asian eels plaguing the St. Lawrence Seaway?. Here, the answer is yes, and no. For the most part, invasive species are aggressive mainly because they find themselves in an environment which contains no natural enemies. If that is the case, fitting the newcomers into a peaceful equilibrium is a matter of restraining their initial invasion long enough for balance to be restored through the inevitable appearance of natural enemies. So, if we apply our little nature lessons to social and economic issues related to foreign immigration, the goal becomes one of restraining an initial influx to a number which can be comfortably integrated with native tribes and clans. In the meantime, we enjoy the hybrid vigor which flourishes from exposure to new ideas and customs.

In the medium time period, that is. For the long haul, if the immigrant tribes really do have -- not merely a numerical superiority -- a genetic superiority for this environment, perhaps we natives will just have to resign ourselves to retreating into caves.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1219.htm

Philadelphia Green

|

| Pennsylvania Horticultural |

The Philadelphia Flower Show is the best in the country. Getting crowds of visitors every March, it would get even more if Convention Hall were bigger. Obviously, it is a financial success for its owner, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. What six or eight million dollars of profits go for is a city-wide outdoor beautification effort called Philadelphia Green. That, too, is the biggest, oldest and best effort of its kind in the country

About a hundred employees and four thousand enthusiastic volunteers spread out over the City, to make it look half-way decent. As the momentum grows, the political strength grows, too; and politicians notice that. The ladies who run this effort hit the school system pretty hard for volunteers and the enthusiasm of inner-city kids for an activity not often seen in the asphalt jungle is very heartening. The Horticultural Society also hits local businesses with appeals; if flower gardens aren't your thing, just give us the money and we'll do it for you.

Philadelphia Green has created four hundred community gardens, seventy neighborhood parks, planted 20,000 trees in 4 years, and vigorously pursued vacant land management. If the ground is hopelessly covered with concrete they bore holes in it to drain off the water, and pour on enough dirt to get grass to grow. Among the many things which volunteers contribute, novel ideas rank high.

Someone approached the Wharton School, and it is asserted that unbeautified vacant lots are worth 18% less than average, while beautified ones are worth 30% more. Since only 10% of the City's many vacant lots have been cleaned up, there's lots of room for economic improvement in the future. But the improvement is already quite visible, isn't it?

REFERENCES

| Standardized Plant Names: American Joint Committee on Horticultural, Frederick Law Olmsted | Google Books |

Philadelphia Gardens

|

| Ernesta Drinker Ballard |

There are many show gardens, mainly on former large estates, scattered around the United States, and the ones on Southern plantations are quite famous.