3 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Gilded Age

They made their fortunes in the West, but spent them in Philadelphia. Until they settled in the West, themselves.

Shakspere Society of Philadelphia

Maybe not the first, but the oldest Shakespeare club in America or possibly even the world, has kept minutes for over a hundred fifty years.

Or perhaps not, but this sort of comprehensive collection of varying interpretations is in the spirit of the Variorum Shakespeare, which was the crowning achievement of this society.

We begin with Shakspere's last will and testament, in order to justify the spelling of his name which the Society chooses to use. Following that, a short description of the sort of people we are in Philadelphia, written by one who was a close observer who felt she never quite belonged.

George Ross Fisher, MemberShakspere's Last Will and Testament

The Last Will and Testament of William Shakspere

"During the winter of 1616, Shakespeare summoned his lawyer Francis Collins, who a decade earlier had drawn up the indentures for the Stratford tithes transaction, to execute his last will and testament. Apparently, this event took place in January, for when Collins was called upon to revise the document some weeks later, he (or his clerk) inadvertently wrote January instead of March, copying the word from the earlier draft. Revisions were necessitated by the marriage of [his daughter], Judith... The lawyer came on 25 March. A new first page was required, and numerous substitutions and additions in the second and third pages, although it is impossible to say how many changes were made in March and how many currently came in January. Collins never got round to having a fair copy of the will made, probably because of haste occasioned by the seriousness of the testator's condition, though this attorney had a way of allowing much-corrected draft wills to stand" (@ Schoenbaum 242-6).

Words which were lined-out in the original but which are still legible are indicated by [brackets]. Words which were added interlinearly are indicated by italic text. The word "Item" is given in the bold text to aid reading and is not so written in the document.

From the first line of Shakspere's will

In the name of God Amen I William Shakespeare, of Stratford upon Avon in the country of Warr., gent., in perfect health and memory, God be praised, do make and ordain this my last will and testament in manner and form following, that is to say, first, I commend my soul into the hands of God my Creator, hoping and assuredly believing, through the only merits, of Jesus Christ my Saviour, to be made partaker of life everlasting, and my body to the earth whereof it is made. Item, I give and bequeath unto my [son and] daughter Judith one hundred and fifty pounds of lawful English money, to be paid unto her in the manner and form following, that is to say, one hundred pounds in discharge of her marriage portion within one year after my decease, with consideration after the rate of two shillings in the pound for so long time as the same shall be unpaid unto her after my decease, and the fifty pounds residue thereof upon her surrendering of, or giving of such sufficient security as the overseers of this my will shall like of, to surrender or grant all her estate and right that shall descend or come unto her after my decease, or that she now hath, of, in, or to, one copyhold tenement, with appurtenances, lying and being in Stratford upon Avon aforesaid in the said country of Warr., being parcel or holder of the manor of Rowington, unto my daughter Susanna Hall and her heirs forever. Item, I give and bequeath unto my saied daughter Judith one hundred and fyftie poundes more, if shee or anie issue of her bodie by lyvinge att thend of three yeares next ensueing the daie of the date of this my will, during which tyme my executours are to paie her consideracion from my deceas according to the rate aforesaied; and if she dyes within the said term without issue of her body, then my will us, and I doe give and bequeath one hundred poundes thereof to my niece Elizabeth Hall, and the fifty poundes to be set fourth by my executours during the life of my sister Johane Harte, and the use and profit thereof coming shall be paid to my said sister Jone, and after her decease the saied l.li.12 shall remain amongst the children of my said sister, equally to be divided amongst them; but if my said daughter Judith be living at the end of the said three years, or any use of her body, then my will is, and so I devise and bequeath the said hundred and fifty poundes to be set our by my executors and overseers for the best benefit of her and her issue, and the stock not to be paid unto her so long as she shall be married and covert baron [by my executours and overseers]; but my will is, that she shall have the consideracion yearly paied unto her during her life, and, after her decease the said stock and consideracion to be paid to her children, if she has any, and if not, to her executours or assignes, she living the said term after my decease. Provided that if such husband as she shall at the end of the said three years be married unto, or at any after, do sufficiently assure unto her and tissue of her body lands answerable to the portion by this my will given unto her, and to be adjudged so by my executors and overseers, then my will is, that the said cl.li.13 shall be paid to such husband as shall make such assurance, to his own use. Item, I give and bequeath unto my said sister Jone xx.li. and all my wearing apparel, to be paid and delivered within one year after my decease; and I doe will and devise unto her the house with appurtenances in Stratford, wherein she dwelleth, for her natural life, under the yearly rent of xij.d. Item, I give and bequeath Shakspere's 1st signature

unto her three sonnes, William Harte, ---- Hart, and Michaell Harte, five pounds apiece, to be paid within one year after my decease [to be sett out for her within one year after my decease by my executors, with advice and direction of my overseers, for her best profit, until her marriage, and then the same with the increase thereof to be paid unto her]. Item, I give and bequeath unto [her] the said Elizabeth Hall, all my plate, except my broad silver and gilt bole, that I now have at the date of this my will. Item, I give and bequeath unto the poor of Stratford aforesaid ten pounds; to Mr. Thomas Combe my sword; to Thomas Russell esquire five pounds; and to Frauncis Collins, of the borough of War. in the county of Warr. gentleman, thirteen pounds, six shillings, and eight pence, to be paid within one year after my decease. Item, I give and bequeath to [Mr. Richard Tyler thelder] Hamlett Sadler xxvj.8. viij.d. to buy him a ring; to William Raynoldes gent., xxvj.8. viij.d. to buy him a ring; to my dogs on William Walker xx8. in gold; to Anthony Nashe gent. xxvj.8. viij.d. [in gold]; and to my fellows John Hemynges, Richard Burbage, and Henry Cundell, xxvj.8. viij.d. a piece to buy them rings, Item, I give, will, bequeath, and devise, unto my daughter Susanna Hall, for better enabling of her to perform this my will, and towards the performance thereof, all that capital messuage or tenement with appurtenances, in Stratford aforesaid, called the New Place, wherein I now dwell, and two messuages or tenements with appurtenances, situate, lying, and being in Henley street, within the borough of Stratford aforesaid; and all my barns, stables, orchards, gardens, lands, tenements, and hereditaments, whatsoever, situated, lying, and being, or to be had, received, perceived, or taken, within the towns, hamlets, villages, fields, and grounds, of Stratford upon Avon, Old Stratford, Bishopton, and Welcome, or in any of them in the said counties of Warr. And also all that messuage or tenemente with appurtenaunces, wherein one John Robinson dwelleth, situate, lying and being, in the Balckfriers in London, nere the Wardrobe; and all my other lands, tenementes, and hereditamentes whatsoever, To have and to hold all and singuler the said premisses, with their appurtenaunces, unto the said Susanna Hall, for and during the term of her natural life, and after her decease, to the first son of her body lawfully issueing, and to the heires males of the body of the said first son lawfully issueing; and for defalt of such issue, to the second son of her body, lawfully issueing, and to the heires males of the body of the said second son lawfully issueing; and for default of such heires, to the third son of the body of the saied Susanna lawfullie yssueing, and of the heires males of the bodie of the said third son lawfully issueing; and for defalt of such issue, the same to be and remaine to the fourth [son], ffyfth, sixte, and seaventh sonnes of her bodie lawfullie issueing, one after another, and to the heires Shakspere's 2nd signature

males of the bodies of the said fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh sonnes lawfully issuing, in such manner as it is before limited to be and remain to the first, second, and third sons of her body, and to their heirs males; and for default of such issue, the said premises to be and remain to my said niece Hall, and the heir males of her body lawfully issuing; and for default of such issue, to my daughter Judith, and the heirs males of her body lawfully issuing; and for default of such issue, to the right heirs of me the said William Shakespeare forever. Item, I give unto my wife my second best bed with the furniture, Item, I give and bequeath to my said daughter Judith my broad silver gilt bole. All the rest of my goods, chattels, leases, plate, jewels, and household stuff whatsoever, after my debts and legacies paid, and my funeral expenses discharged, I give, devise, and bequeath to my son in law, John Hall gent., and my daughter Susanna, his wife, whom I ordain and make executors of this my last will and testament. And I do entreat and appoint the said Thomas Russell Esquire and Frauncis Collins gent. to be overseers hereof, and do revoke all former wills, and publish this to be my last will and testament. In witness whereof I have hereunto put my [seale] hand, the date and year first above written.

Witnes to the publishing hereof Fra: Collyns Julius Shawe John Robinson Hamnet Sadler Robert Whattcott

Shakspere's final signature, 'By me ...'

The Definition of a Real Philadelphian (1914)

|

| Elizabeth Robbins Pennell |

There are several million people living in Philadelphia, but of course, not all of them are real Philadelphians. >Elizabeth Robbins Pennell, a friend and biographer of James McNeill Whistler, tells us the definition of a real Philadelphian in 1914.

"I think I have a right to call myself a Philadelphian, though I am not sure if Philadelphia is of the same opinion. I was born in Philadelphia, as my father was before me, but my ancestors, having had the sense to emigrate to America in time to make me as American as an American can be, were then so inconsiderate as to waste a couple of centuries in Virginia and Maryland, and my Grandfather was the first of the family to settle in a town where it is important, if you belong at all, to have belonged from the beginning. However, [my husband's] ancestors, with greater wisdom, became at the earliest available moment not only Philadelphians, but Philadelphia Friends, and how much more that means Philadelphians know without my telling them. And so, as he does belong from the beginning, and as I would have belonged had I had my choice, for I would rather be a Philadelphian than any other sort of American, I do not see why I cannot call myself one despite the blunder of my forefathers in so long calling themselves something else."

--Our Philadelphia, 1914

Neglection

|

| William Lyon Phelps |

Billy Phelps, that's William Lyon Phelps, once remarked he had watched a performance of every single Shakepeare play, except two. That put the idea in my young impressionable head, and eventually, my wife and I watched a performance of every single one of those plays. Some of these blur in my recollection, a little. And although watching those thirty-six performances was a great overall experience, I would have to say that about fifteen of them seemed very poor. It's particularly vexing that several of the bad plays were written after most of the divinely wonderful ones, so their poor quality can't be blamed on inexperience, and the whole thing is a little hard to explain.

Indeed, if you did nothing but read the plays, you would think many more of them are of poor quality. But in the hands of a clever director, the bloody plays like Titus Andronicusare extremely effective; one easily sees why Elizabethan audiences flocked to see the melodrama. That's also true of the scenes of shipwrecks and storms , as seen in The Tempest and ,Pericles, or on land in King Lear. And the silly little comedies, with ladies in disguise or twins confused, are delightful little jigs on the stage when you actually see them performed. The experience leads to the question whether some of the other plays are not poor at all, just misunderstood.

After sixty years of intense devotion to a scientific specialty, the Shakespere Society of Philadelphia created a refuge to return to. After long sensing that scientific colleagues regarded attendance at thirty-six plays as a strange quirk, there was a group which regarded it as an achievement to be respected. A group which understood that the only times Shakespeare signed his own name, he spelled it, Shakespeare. And who took seriously the idea that some of the inferior plays in the canon might well have been written, wholly or in part, by some other person.

It thus happens that this group, after fifty years of avoiding it, was restudying Pericles. The tradition has been that this secondary play was written about the same time as King Lear, although it is hard to believe. Eminent scholars regard the first two acts as having been written by someone else, while the last three acts were written by Shakespeare, but this group thought it questionable that any of Pericles measured up to standard. The speeches are choppy, the plot jumps all about, the characters seem unreal. And then we come to neglection. As in the speech by

Frank Furness,(3) Rush's Lancer

|

| Frank Furness |

Lunch at the Franklin Inn Club was recently enlivened by David Wieck, who not only does the sort of thing you get an MBA degree for but is also a noted authority on the Civil War. His topic was the wartime exploits of Frank Furness, whose name is often mispronounced but whose thumbprints are all over the architecture of 19th Century Philadelphia. Take a look at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy, the Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania, and many other surviving structures of the 600 buildings his firm built in 40 years. One of them is the Unitarian Church at 22nd and Chestnut, where his grandfather had been the fire-brand abolitionist minister.

|

| PennsylvaniaAcademy of Fine Arts |

The Civil War seems to have transformed Frank Furness in a number of ways. He had been sort of in the shadow of his older brother Horace, a big man on the campus of Princeton, later the founder of the Shakspere Society, and the Variorum Shakespeare. Frank was quiet, and good at drawing. However, at age 22 he was socially eligible to join Rush's Lancers, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which contained among other socialites the great-grandson of Robert Morris, and a member of the Biddle Family who put up the money to equip the troop with 7-shot repeating rifles. Cavalry units like this were a vital weapon in the Civil War because they needed young well-equipped expert horsemen with a strong sense of group loyalty. Rifles were considered too expensive for infantry, who were equipped with muskets that took several minutes to reload, and were unwieldy because they were only accurate if they were very long. When bands of daredevils on horseback suddenly attacked with seven-shot repeating rifles, they could be devastating against massed infantry. A flavor of their bravado emerges from their rescue of General Custer's men from a tight spot, later known in the annals of the troop as "Custer's first last stand."

|

| The Undine Barge Club Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy |

There are two famous stories of the exploits of Frank Furness, first as a second Lieutenant and later as a Captain at Cold Harbor two years later. In the first episode, a wounded Confederate soldier lay on the no man's land of forces only a hundred yards apart. His screams were so heart-rending that Furness ran out to him and put a handkerchief tourniquet around his bleeding thigh. Because the fallen man was a Confederate soldier, the Confederates held their fire and later cheered the Union cavalryman for his kindness. The wounded man called out "

|

| The Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania |

In the second episode, the cavalry had spread out too much, leaving some isolated parties trapped and out of ammunition. Furness lifted a hundred-pound box of ammunition to his head and ran through the gunfire with it to the trapped men. For this, he later received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Somehow all of the public attention he received in the war transformed Furness from a younger brother who was good at drawing into a dynamo of energy, much in the model of what law firms call a "rainmaker". He traveled to the Yellowstone area of Wyoming at least six times, bringing back various trophies. He was known to get people's attention by using his service revolver to take pot shots at a stuffed moose head in his office.

|

| First Unitarian Church 22nd Chestnut Philadelphia |

His final publicity venture was to advertise, forty years later, in Southern newspapers for the whereabouts of the Confederate soldier whose life he had saved. Eventually, a man named Hodge who had later been a sheriff in Virginia, stepped forward to renew his blessings and thanks. Hodge was brought to Philadelphia for a celebrated 6th Cavalry reunion, and a picture of the two former enemies was spread in the newspapers. It was a little embarrassing that Furness and Hodge found they had very little to say to each other for a five-day visit, but Hodge eventually proved able to be one-up in the situation. He outlived Furness by five years.

Although the style of Furness confections seemed and seems a little strange to everyone except Victorian Philadelphians, he did leave a major stamp on American architecture. His most noted student was Louis B. Sullivan, who put an entirely different sort of stamp on Chicago. And Sullivan's best-known student was Frank Lloyd Wright who created a modernist image of architecture for the West. The buildings of these three don't look at all alike, but their rainmaker personalities are all essentially the same.

Shakspere Society, 150th Annual Dinner April 23, 2001

THE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTIETH ANNUAL DINNER OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA ON SHAKSPERE'S BIRTHDAY, APRIL 23,2001, AT BOLINGBROKE, RADNOR, PA.

Members present at the auspicious occasion of the sesquicentennial annual dinner of the Society: Ake, Baird, Bartlett, Binnion, Bornemann, Cheston, Cooke, Cramer, Di Stefano, Dobson, Dunn, Dupee, Ervin, Fallon, Fisher, Friedman, Frye, Green, Griffin, Hanna, Hopkinson, Horwitz, Ingersoll, O'Malley, Peck, Pickering, Rivinus, Schlarbaum, Scott, Wagner, Wheeler.

Dean Wagner, resplendent in his ceremonial chain of office, greeted a particularly festive and numerous gathering at this year's annual dinner to honor the Bard on his birthday: for the first time, the Society welcomed the spouses and partners of many of the members to the annual dinner. We all owe a deep debt of gratitude to the hosts of this splendid feast: Frank Baird, Peter Binnion, Gary Schlarbaum and Philip Wagner. Our brief formal proceedings before dinner began with a moment of sympathetic silence honoring the memory of Louisa Foulke, the recently deceased wife of 67 years of the much esteemed senior member of our Society, Bill Foulke. The Dean paid eloquent tribute to the retiring Vice Dean, our dear friend, Roland Frye, who has guided the members' after-dinner discussions of the Bard's plays with tact, patience, learning, and wit for many years. We welcome with enthusiasm our new Vice Dean, the erudite Robert Thomas Fallon, who so ably led our discussions during the past season. The other officers of the Society will continue to exercise their responsibilities next season: Dean Wagner, Secretary for Minutes Peck, Secretary for Meetings Di Stefano, Treasurer O' Malley, and Librarian Binnion. Business concluded with admirable efficiency, the feast began! The gentlemen's elegant but sober formal garb set off, by contrast, the beautiful and graceful attire of the ladies we welcomed enthusiastically to our midst on this gala occasion. In the midst of our sumptuous repast, the Dean led the assembled gathering in the traditional birthday dinner toast: "To William Shakspere!" Members' souvenirs of this memorable moment in our Society's history included not only the traditional menu of the feast, with appropriately witty quotations from this year's plays by Sweet William, but a special poster in living color memorializing our sesquicentennial gathering. Onwards and upwards! Per Aspera ad Astra! And still, he cried "Excelsior!"

Respectfully submitted, Robert G. Peck, Secretary for Minutes

Shakspere Society October 10,2001

.MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, OCTOBER 10, 2001

The Shakspere Society began its new season, happy to meet again at the Franklin Inn Club, with Dean Wagner in the chair, and the following members in attendance: Binnion, Bornemann, Cramer, DiStefano, Dunn, Fallon, Friedman, Green, Griffin, Hopkinson, Lehmann, Madeira, O'Malley, Peck, Pickering, Simmons, Wagner, Wheeler. Vice Dean Fallon's son Rob Fallon, an environmentalist from Oregon, was present as his father's guest, heartily welcomed by all. Dean Wagner began with some unhappy news about our members: Harry Langhorne died in Virginia last May; Jodie Dobson's son Mark died in early September. The members of the Society extend their heartfelt sympathy and condolences to a member of Harry Langhorne's family and to our dear friend Jodie Dobson. Roland Frye has suffered from bad health but is recovering and is expected back among us shortly, we were very happy to hear. Jim Warden, after several years in London, is now back in Philadelphia, and we hope to see him at dinner with us in the near future. Jim Massey, who is living in London, has resigned his membership in the Society.

Your scribe was asked by the dean to say a word about his playgoing travels this summer. I was the grateful recipient of a grant from the Haverford School parents so that my wife Leila and I could spend two weeks in London and Stratford, and then five days in Niagara on the Lake, Ontario, seeing plays. All in the name of duty, my friends. We saw Macbeth and King Lear at the new Globe in London, and in Stratford King John, Twelfth Night, and Hamlet. The Globe provides a remarkably intimate ambiance for playgoing relative to the size of the audience in attendance, standing around the platform and sitting in the two tiers of balconies. One is very conscious of the other theatergoers'distracting to some but to mean intensification of the emotional impact of seeing these plays. The Lear was largely traditional in concept, aside from some marginal gimmickry in staging. The acting was crisp, energetic, forceful, especially the work of the women. But the language was rushed, I thought: the focus was on action, blocking, pacing, not on eloquent poetry. That was even more true of the Macbeth, which was funny and lively in the treatment of the witches (party hats, kazoos, grotesque dances, comic voices), and always clever in staging. Lady M was chilling, arresting, powerful. But where was the anguish of Macbeth and his queen? Where was the moral crisis each one faced, the religious judgment Macbeth felt with such agony in the play's late scenes? Where was the actor who would treasure the most wonderful language ever written in English for the stage? In Stratford, a lively, extravagant pageant for King John, which your scribe wrote about at excruciating length for his dissertation and never expected to see on stage in this life; a uniformly spectacular Twelfth Night, captivating in every scene, every speech, every word of dialogue'although the Viola might have been more varied, artful and nuanced in her speeches of love; and an impressive but rather cold Hamlet, spectacular rather than moving. The staging of Hamlet was wonderfully suited to the play's psychological world: a huge and bare stage, lighting either cold and glaring or deeply obscured; characters often physically separated from each other by huge sterile spaces so that speeches seemed launched into emptiness, unheard or unheeded by others. The ghost, for once, was not silly or flat or embarrassing. But Hamlet, though articulate and intense, speaking every word with crisp conviction, seemed irritable, angry, gloomy, depressed' but never a man facing ultimate questions about the meaning of life and the nature of familial or erotic love.

As to the Shaw, no Shakspere, but eight shows, all wonderfully well staged and acted. One was a stinker, Edwin Drood, but the others great fun, and the production of Pirandello's Six Characters a revelation about the psychological power of a play I had seen as only of Philosophical interest.

Bill Madeira reported that a summer Twelfth Night was beautiful in staging'" like a Watteau"' and enlivened by fine acting, especially the work of Paxton Whitehead as Malvolio. The PA Shakspere Festival put on a wonderful Romeo this summer; Bob Fallon thought the Juliet especially fine. A recent Princeton Romeo production at McCarter was criticized in comparison. Winter's Tale in Williamstown featured a remarkable performance by Kate Burton. (Your scribe has just seen MissBurton as an arresting Hedda Gabler on Broadway' but in his opinion, our friend Grace Gonglewski offered a more nuanced and complete portrait two seasons ago at the Arden). A portrait of an Elizabethan man has appeared in Ontario which purports to show the Bard at 39. It evidently dates from the early 1600's, but whether the subject is Shakspere is debatable.

Vice Dean Fallon introduced our reading and discussion of Antony and Cleopatra. The play is a sequel, historically, to Julius Caesar, though written perhaps eight years later, after the other major tragedies of the Bard. The action covers about ten years, from 40 till 30 BC (BCE to politically correct readers). The second triumvirate has divided the empire. Antony rules all the Roman lands east of the capital. He has gone to Egypt and become entranced, mesmerized, drugged by Cleopatra. Antony is 42, the queen 29'old enough in the ancient world so that in the play she is haunted by the specter of age. Cleo is Shakspere's best portrait of a mature woman. She is a legend: even in Rome, she is the principal subject of gossip and worry. She keeps her hold on Antony by constantly keeping him off balance, surprised, defensive, puzzled, charmed by her changing moods. Cleo's magic is in her language, as rich and varied as the words the master gave to any of his creations. The Roman Enobarbus is a frequent commentator on Cleo's words and actions, how she keeps Antony from his Roman duty. Egyptian decadence is dramatized in early scenes: "sensuous, self-indulgent, trivial," in the vice dean's words. In scene two, Antony tries to recover his sense of Roman duty, reflecting on the death of his wife: "She's good, being gone"'and determines that he must "from this enchanting queen break off" and return to Rome. "These strong Egyptian fetters I must break/ Or lose myself in bondage," says Antony, reprogrammed for the moment as a dutiful Roman. In scene three, Cleo plays her usual part: "If you find him sad, / Say I am dancing; if in mirth, report/ That I am sudden sick." But Antony declares that duty calls him to Rome, though "my full heart/ Remains in use to you." Cleo accuses him of "excellent dissembling" in declaring love, that she is "all forgotten." Antony hotly declares that "I should take you for idleness itself." Rome rules in him'for the moment.

OUR NEXT MEETING IS WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 24.

Respectfully submitted, Robert G. Peck, Secretary for Minutes

Shakspere Society October 24, 2001

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, OCTOBER 24, 2001

In the absence of Dean Wagner, Dean Emeritus Hopkinson in the chair. Other members present Baird, Bartlett, Bornemann, Cramer, DiStefano, Dobson, Dupee, Fallon, Fisher, Friedman, Green, Griffin, Ingersoll, Madeira, Peck, Pope, Rivinus, Schlarbaum, Warden. Guest: Robert Fallon, Jr.

Your scribe apologized for defective minutes for the last meeting that went out to ten members; a complete minutes for the meeting of October 10, 200l is included with this mailing. Announcement was made of the fact that the Shakspere Festival of Philadelphia (producing its work upstairs at the Lutheran Church at 21st and Sansom Streets) is currently staging the Bard's historically seldom staged but currently rather fashionable late romance Cymbeline (probably written just a couple of years after our current play for reading, Antony). We were informed that our dear fellow member Roland Frye finds it a bit difficult to answer the telephone but would love to hear from his friends by mail. A new address list of members is currently in preparation; if you have not yet informed Secretary for Meetings DiStefano of changes of address or e-mail address or telephone number, please give him a call soon.

Vice Dean Fallon commented briefly before we began our reading of the second act of Antony and Cleopatra. Romantic passion did not express itself on Shakspere's stage by physical embraces and kisses, underscored by surging orchestral accompaniment, in the style of close-ups in Hollywood films. Cleopatra, we must remind ourselves, was a preadolescent boy wearing a dress. (But what an actor he must have been for the bard to dare to write this part for him! Was he the same dazzling talent for whom the master created Lady Macbeth just a few months earlier?) Language creates sex appeal and passion in this play. The Vice Dean reminded us of the importance of the comments of Enobarbus as a shrewd and often sarcastic observer of this love affair: an analyst both repelled by his master's weakness in yielding to Cleopatra's seductive power and fascinated himself by the Egyptian queen's witchery. Cleo must maneuver between Antony and Octavius in order to keep her throne and to keep Egypt from succumbing completely to Roman power. Does love rule in Cleo or political desire? Or is it impossible to separate the two in her motives and actions? --In Act Two, the young Pompey is in rebellion against the triumvirate of Octavius, Antony, and Lepidus, eager to rehabilitate the reputation of his father, once cheered by the Roman mob, killed in battle by Julius Caesar. The young man negotiates tensely with the triumvirs late in the act, after several scenes of tense negotiations between Octavius and his elder political partner and rival Antony. Both episodes end with peace pacts, but peace is clearly superficial and strained in both cases; we wait for explosions to come.

II.Pompey hopes Cleo will keep Antony hypnotized so as to prevent unity and military readiness among the triumvirate: he hopes that the lustful or "salt Cleopatra" will use her "witchcraft" to create "charms of love" so that the veteran seductress's "waned lip" will keep its power to "Tie up the libertine in a field of feasts" spiced by "cloyless sauce" that will endlessly sharpen Antony's appetite and dull his sense of honour. Pompey is then startled to hear that the Roman in fact is in the field, that military duty "Can from the lap of Egypt's widow pluck/ The ne'er-lust-wearied Antony."

II.iiOctavius, reunited with Antony, vigorously attacks him for dereliction of duty and wonders whether the latter did not "practice on my state" while away from Rome. Antony is hotly indignant: "My being in Egypt, / Caesar, what was't to you?... How intend you, practis'd?" Antony's relatives have warred on Octavius in Antony's name against Antony's desires, he insists. Octavius sneeringly replies, "You patch'd up your excuses" and ignored his partner's letters to Egypt "when rioting in Alexandria." Antony admits to a disabling hangover or three, but the attack goes on: "You have broken the article of your oath." "It cannot be," Octavius says a bit later, "we shall remain in friendship." But Antony leaps at the suggestion that he marry his partner/rival's sister Octavia so as to bind up past strife between them. When the great men depart, Enobarbus is grilled by his Roman friends about the orgies of Egypt. He replies with his wonderful speech about Cleo's barge on the Nile, which "like a burnish'd throne/ Burn'd on the water." Cleo conquers nature, which serves her and makes her seem a goddess. She has spellbound Antony with her pageants of beauty and with her intense and endless energy, sometimes expressed in baroque ceremonial, sometimes in its opposite: "I saw her once/Hop forty paces through the public street,/And having lost her breath, she spoke and panted,/That she did make defect perfection,/And, breathless, power breathe forth." Antony will never leave her, since "Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale /Her infinite variety. she makes hungry,/ Where most she satisfies."

II.iii Antony shows that Enobarbus is right: "I will to Egypt;/ For though I make this marriage for my peace,/ In th' East my pleasure lies." Antony moves his place, but once moved, yearns to be elsewhere.

II.v---In Egypt, Cleo wonders with her ladies how to keep Antony in the same way as "I will betray/Tawny-finn'd fishes [on] my bent hook." She recalls their erotically playful cross-dressing, he as Queen Cleo, she armed with his sword. She hears the horrid news of Antony's marriage. Cursing the messenger, she "strikes him down" and "hales him up and down," in the wonderfully vivid stage directions of the old Arden edition, saying to him, "I'll spurn thine eyes/ Like balls before me."

II.vi---Back in Sicily, Pompey parleys and parties with the triumvirs and strikes a deal that avoids battle much to the disgust of his father's old military companion Menas, who had tried to get young Pompey to cut his rivals' throats while he had the chance. The young man would have loved the deed, but honor will not permit him to arrange it himself.

III.i---In this scene in Parthia, always cut in production, Ventidius refrains from gaining too great a victory for Rome over the Parthians glory must be reserved for Antony!

OUR NEXT MEETING WILL BE HELD ON NOVEMBER 7, 2001

Respectfully submitted,

Robert G. Peck , Secretary for Minutes

Shakspere Society November 7, 2001

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, NOVEMBER 7. 2001:

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members attending: Ake, Bornemann, Di Stefano, Dobson, Dunn, Fallon, Fisher, Green, Griffin, Madeira, Peck, Pickering, Pope, Simmons, Warden, Wheeler. Guest: J. Goldstein.

The Dean announced the happy news that Messrs. Green, Dunn, and Cramer have volunteered to host the 2002 annual dinner of the Society in honor of the Bard's birthday. We were concerned to hear that Matt Dupee has had to undergo a heart catheterization procedure, but "heartened" to know that all has gone well. An up-to-date directory of the membership is included with these minutes, courtesy of our indefatigable Secretary for Meetings. As we prepared to read after dinner, we welcomed to our midst the current president of the Franklin Inn Club, Jonathan Goldstein.

We began our reading with Act Three, Scene Two of Antony and Cleopatra, and we read through the rest of this long and complex act. The text stimulated one of the most animated evenings of discussion in recent memory, with almost every member present anxious to air his views on one point or another. The Vice Dean stressed the rapid change of scenes and shifting settings of the action. A member recalled hearing in his youth Lord David Cecil's lecture on the play at Oxford, and Cecil's emphasis on the importance of panorama in Antony. In III.ii, we are touched by the painful parting of Octavia from her brother Octavius, who is so cold to all but his sister. Antony and his new bride are off to Greece, but we know where Antony's next travels will take him!

III.iii We are with Cleopatra and her court in Egypt. "Time stopped" while we were in Rome with Antony, commented the Vice Dean: Shakspere continues with the action in Egypt exactly where he left off in the last Egyptian scene in Act Two. The messenger from Rome, whom she beat earlier for unwelcome news, now carefully tells her what she wants to hear: Octavia is short, has a low forehead, is dull in speech, and worst/best of all, she is thirty!

III.iv--- Antony is furious at Octavius for insults to him and loudly tells his new wife that he must defend his honor. Poor Octavia speaks eloquently of her divided loyalties, and of the terrible bloodshed that will follow if Antony does not restrain himself: "Wars ' twixt you twain would be/As if the world should cleave, and that slain men/ Should solder up the rift." She goes to seek her brother and to try to mend the quarrel; Antony has travel plans of his own the minute his new wife has turned the corner. A member commented on the interesting contrast of Octavia, full of moral integrity, to the scheming and selfish Cleopatra.

III.vi---Octavia pleads with her brother to make up the quarrel with her husband, but Octavius is as bitter against Antony as the latter is against him. He tells his naively unbelieving sister that her husband "gives his potent regiment to a troll." Octavius has had Lepidus liquidated, and has seized his possessions; the Vice Dean pointed out that Octavius made no effort to justify this gangland hit against a weaker rival for power. Octavius is "all business, a prig" so we are more sympathetic to Antony than we would otherwise be, despite his petulance and his adolescent emotional impetuosity. Antony has won big battles and has the respect of his veterans; Octavius, his rival, wins no hearts. But Antony is tied to Cleopatra, who to Romans is the very incarnation of moral decadence.

III.vii---Antony makes an irrational, unexplained decision to fight on sea, not on land, where he is the legendary world champion, against Octavius at Actium. Enobarbus eloquently protests, to no avail. Shakspere implies, without explicit statement, that Antony follows Cleopatra' swill in this disastrous decision. He then flees the battle when she does, leaving the field for his rival. Is Cleopatra testing Antony's love? Is she protecting the Egyptian fleet? Is she only interested in protecting Egypt's interests, irrespective of Antony's fate? The Vice Dean commented on the notable contrast between Cleopatra and Elizabeth's brave eloquence addressing her troops when the Spanish threatened invasion when the Armada sailed in 1588. As to Cleo's influence over Antony, a member commented on the parallel to Lady Macbeth's disastrous influence on Macbeth in the play that the Bard probably wrote just before Antony.

III.x---Antony sails after the fleeing Cleo. The Roman Scarus comments that "Experience, manhood, honor, ne' er before/ Did so violate itself." Roman commanders plan to kneel to Octavius. Enobarbus stays with Antony, though reason argues against him.

III.xi---Antony, bitterly ashamed, asks his commanders to divide his gold and be gone to safety. Cleopatra enters to him; Antony condemns her influence over him while acknowledging how completely she commands him. But once she has asked pardon, he is wholly in love again: "Fall, not a tear, I say, one of them rates/ All that is won and lost."

III.xii---Antony in humiliation must send a mere schoolmaster to bargain with Octavius. Octavius will not listen to Antony's requests to retire to Greece to private life, but Cleopatra will be protected if she kills or hands over Antony to his rival.

III.xiii---Thidius, sent by Octavius to Cleopatra, is found kissing her hand by Antony, who has him whipped a shocking offense to Octavius. Antony challenges Octavius to a duel to settle their quarrel, provoking satiric scorn from Enobarbus. But Enobarbus struggles to justify staying true to Antony. As Cleopatra flatters Octavius' agent, Enobarbus declares that he must "find some way to leave" Antony. Cleopatra finds wonderful language to claim Antony's love once again. Antony, swinging from despair to jubilation, calls, "Come,/ Let's have one other gaudy night: call to us/ All my sad captains, fill our bowls once more." But Enobarbus hears only the voice of irrational infatuation, and declares, "I will find some way to leave him."

OUR NEXT MEETING WILL BE ON NOVEMBER 28. WE WILL BEGIN OUR READING AT ACT FOUR, SCENE ONE

Respectfully submitted Robert G. Peck Secretary for Minutes

Shakspere Society November 28, 2001

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, NOVEMBER 28, 2001:

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members present: Bartlett, Binnion, Bornemann, Cramer, Di Stefano, Dupee, Fallon, Fisher, Green, Hanna, Hopkinson, Madeira, Peck, Simmons, Warden, Wheeler.

Your scribe apologizes for a mistake in the last meeting's minutes: the current head of the Franklin Inn Club was not among us during that meeting, but we expect to greet him soon.-- Notice was taken of an article in a July issue of U.S. News, on the views of that hardy crew that insists that the Earl of Oxford wrote the Bard's plays. Appended documents quote a long list of famous actors and scholars who have swallowed this nonsense over the past few decades. Your scribe will provide a short digest of these documents at the next meeting, and in the minutes of that meeting. --Members are asked to inform Secretary for Meetings Di Stefano that they wish to attend a meeting at least twenty-four hours in advance of that meeting. A member called our attention to the fine chapter on Antony in the recently published collection of lectures on Shakspere by W. H. Auden. This was Auden's favorite of the Bard's plays. To Auden, the historical material is not important; the personal relationship of the two lovers gives the play its power because that is what kindles Shakspere's imagination and brings to life its extraordinary language. Cleopatra's desertion of Antony at Actium is the great crux of this relationship, in Auden's view. Only two members have been lucky enough to have seen productions of this play in the theater; one in Central Park, one in London with the great Helen Mirren as Cleopatra but Miss Mirren was roundly panned by the reviewers for her work in this production!

We began our reading with Act Four, Scene Two of Antony. Vice Dean Fallon noted that in Scene Two, Antony predicts his death, and reminded us that when a character has such premonitions in a play of the Bard, that death is sure to occur. All the rest of the play is set in Alexandria, in contrast to the vast geographical sweep of earlier scenes.

4.3A famous moment: unearthly music is heard, and a guard comments, "Tis the god Hercules, whom Antony lov'd, / Now leaves him." The Vice Dean pointed out that there is little of the supernatural in this play, as is generally true of Shakspere's plays. Macbeth and Hamlet are of course the notable exceptions, and we recall the brief appearance of Caesar's ghost to Brutus late in Julius Caesar. (One might also think of the wonderful moment when Hermione's "statue" seems to come to life at the end of The Winter's Tale. Her overwhelmed husband's reaction: "If this is magic, let it be an art/ Lawful as eating!")

4.4---A comic moment in preparation for the disaster at Actium that seals the fate of the famous lovers: Cleopatra "helps" Antony arm for battle, and of course is all thumbs, childishly ignorant about battle armor, costume from a realm alien to Egypt's erotic enchantress. The lovers play, as they do so often, it was pointed out; but the scene is poignant to auditors and readers. We know the story: soon they will both die.

4.5, 4.6---Enobarbus finally leaves Antony, after delaying almost as long as Hamlet in doing what he feels he must do. Once in Caesar's camp, he is full of remorse and self-castigation, vowing, "I'll not fight thee." In 4.9, Enobarbus commits suicide, saying, "My revolt is infamous" and denouncing himself as "A master-leaver." It was remarked that these final scenes with Enobarbus enhance Antony's character in our minds, since his often cynical, witty, unsparing critic is so despairing at leaving his master.

Actium: Cleopatra for the second flees the battle scene. Antony immediately declares that "All is lost./ This foul Egyptian has betrayed me." Her motives? We do not know them, but Antony is certain that her desertion is calculated, and he loses all will to carry on his contest with Caesar. However, we were reminded, in the play's final scenes Cleopatra seems utterly loyal to Antony, full of grief, devotion, love. Almost all their followers leave them, so they are left to focus entirely on each other and their intense mutual devotion, as Antony dies in his lover's arms.-- Antony has fallen on his sword earlier, after his loyal servant Eros has killed himself rather than fulfill his promise to kill his master to save him from capture and public humiliation in Rome. Members commented on the many repetitions of the name "Eros" by Antony in this scene, with its powerful symbolic overtones. -- Finding Antony's corpse, the victorious Caesar grieves and praises his great adversary--as he had, we were reminded, over the corpse of Brutus at the end of Julius Caesar. Caesar, a member remarked, has lost his most splendid opportunity to shine in the public arena now that his greatest adversary is gone.

Our next meeting is December 12, 2001. We will begin reading with Act Five, Scene Two of Antony and Cleopatra. We will then start reading our next play for study and discussion, Measure for Measure.

Respectfully submitted, Robert G. Peck, Secretary for Minutes

Shakspere Society December 12, 2001

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, DECEMBER 12, 2001:

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members present Ake, Bartlett, Binnion, Bornemann, Cheston, Di Stefano, Dobson, Dunn, Dupee, Fallon, Griffin, Hopkinson, Madeira, O' Malley, Peck, Rivinus. Guest: J. Goldstein.

We were very happy to welcome to our midst the president of the Franklin Inn Club, Jonathan Goldstein, who read the words of the Bard with vigor and commented crisply and thoughtfully on the fifth act of Antony and Cleopatra. He welcomed us and assured us of the members' pleasure at our regular use of their clubhouse. Jonathan has found a number of old Shakespeare texts in the library of the Franklin Inn Club that evidently have been left here at various times by members of the Society, and he has kindly donated or sent back to their place of origin these copies of the Bard's plays.

A member pointed out to us that beginning on December 23, thee will be versions of some of Shakspere's most famous plays presented on TV on the ITV cable network. The descriptions in print of the plots of these versions look like a bad joke, but if they arouse serious interest in the work of the Bard among a few of the young who might see these telecasts, Honi Soit qui mal y sense.

Mr. Griffin told us that he had recently had lunch with his Princeton classmate, our great good friend, and fellow member Roland Frye and that the Vice Dean emeritus had announced that he was "alive and well and living in Strafford." Secretary for Meetings Mr. Di Stefano asked that all those who had changed addresses recently would let him know promptly.

A member told us of his visit to a recent production of Macbeth at the Shakspere theater at the Folger Library (the scholar J.Q. Adams' version of the Globe in smaller dimensions, designed a half-century ago), with Huey Long's Louisiana as the setting, and the witches as political appointees assigned the task of vote counting. No report of hanging chads was forthcoming. Another member saw a recent production of Hamlet at the Shakspere Theater of Washington, enjoyed the work of Wallace Acton as Hamlet, but commented on the jarring nature of the introduction of modern rifles and soldiers' helmets adorning the armies in the battle scenes at the end of the play.

We commenced our reading of Antony and Cleopatra at the beginning of the long final scene, Act Five, Scene Two. Cleopatra confronts Caesar and negotiates to save her life. She first speaks to her courtiers about her readiness to kill herself rather than be humiliated, to do that great deed "which shackles accidents and bolts up change," in her wonderfully eloquent summary of the Roman stoic philosophy which guided Brutus and Cassius at the end of their lives. Antony, we were reminded, had told her that she should trust only Proculeius, but he in fact betrays her. Dolabella is her only trustworthy friend among the Romans, as in Plutarch, Shakspere's source. Cleopatra wants the throne of Egypt to descend to her sons; Caesar agrees, but in fact, Dolabella tells her, he intends to lead her captive to Rome to show off in a triumphal procession. We wonder if she will be able to kill herself before this humiliation which she has feared occurs.

A member commented on the jarring combination in Cleo. of eloquent nobility and her attempts to cling to Egyptian treasure for herself or her children. Members remarked on her usual duplicity here, wanting to keep power and to please others. She sees that Caesar is lying and trying to exploit her. Another member declared that Cleopatra never struggled with a moral question, in contrast to Antony, a more impressive figure.

Cleopatra prepares herself for death in a scene with a bizarrely comic element, the clown who brings her the poison asp that kills her. The Vice Dean commented on the appropriateness of a comic touch at this point, since her death is also her victory over Caesar. But of course cheek by jowl with farce we find some of the most gloriously moving language ever written in English. Iras tells the Queen, "Finish, good lady; the bright day is done,/And we are for the dark." Does any other minor character in Shakspere speak so eloquently in so few words? Cleo. thinks with vivid disgust of an adolescent boy (which, in fact, the actor of this part was in 1607) parodying her in the Roman theater: "I shall see/Some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness/ I' the posture of a whore." When she is ready to face death, she declares herself "marble-constant, now the fleeting moon/Is no planet of mine." She dresses ceremonially for death: "Give me my robe, put on my crown: I have/Immortal longings in me. husband, I come/ Now to that name my courage prove my title! In a wonderful coup de theatre underlined by the Vice Dean, her companion Charmian reaches over to straighten Cleopatra's crown as she dies: "Now boast thee, death, in thy possession lies/ A lass unparallel'd. Your crown's awry:/I' ll mend it, and go play."

Cleopatra is eloquent and brave at the end, but she betrays Antony perhaps three times earlier in the play. Members puzzled over her motives: to keep Antony's love and also protect her power, and her sons' a chance to inherit power? Does love of Antony or of self dominate her? A member had the good luck to see Anthony Hopkins and Judi Dench perform the parts of A and C in England in 1987. "They bring out the worst in each other," this member thinks of A and C, and Antony is the more important of the two, but both are sympathetic to the audience in contrast to the obnoxious, egotistical prig Caesar! A and C, others concluded, must be seen as a pair, not separated so that one can be blamed more than the other for the fall of both.

We turned to a few comments on our next play for study, Measure for Measure. A member recalled that Roland Frye had worked on the play when writing his doctoral thesis, after discovering that in a copy of the First Folio in the library of the Escorial in Spain, a part of the text of the play had been excised by a reader evidently appalled that the Duke would have the effrontery to take on a disguise and play the false part of a Catholic priest.

The Vice Dean reminded us that Measure for Measure is not a love story but an "Un-love story" where political power is the chief focus: corrupt authority both denies love and tries to force sexual compliance by threat.

Our next meeting will be January 9, 2002. We will begin our reading of Measure for Measure at that time.

Respectfully submitted, Robert G. Peck, Secretary for Minutes

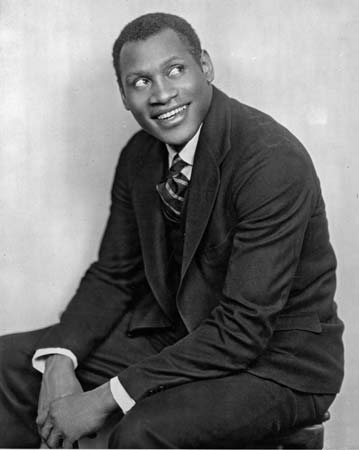

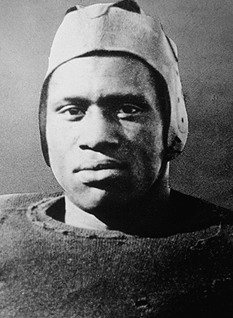

Paul Robeson 1898-1976

|

| Paul Robeson 1898-1976 |

Everyone with international fame and fortune seems to belong to another planet, but Paul Robeson belongs to the Philadelphia region as much as to any locality. He was born in Princeton, of a black minister who went to Lincoln University, and a mother of Quaker heritage. Not only an All-American football player, but he also won twelve varsity letters. He not only was accepted to Columbia Law School, but the only black person in the class became its Valedictorian. Later on, his amazing baritone voice made him the perfect person to sing "Old Man River" in the musical Showboat, and quite a different dimension emerged in his highly memorable portrayal of

|

| Paul Robeson as Othello |

Shakespeare's Othello. He was combative athlete, nobody's fool, and had a commanding stage presence. It was scarcely surprising that he resented the social slights he encountered in his upward mobility, or in a time when many people -- not just in show business -- were leaning leftward, that he frightened people with his praise of Communist Russia and seeming incitement of his race to rebellion.

Probably the first false note in this tragedy was his resignation from a prestigious New York law firm because a white secretary insulted him. No defensive explanation from his admirers could quite justify this unlikely story of a promising career cast aside for a trifling affront. Some of his foreign travels may have been entirely motivated by a search for social progress, but his several hospitalizations abroad do raise the possibility that he hoped to avoid publicity about his illness. The last two decades of his life were destroyed by undeniable mental illness. There are schools of the psychiatric theory which contend that depression can be caused by severe life stresses, but majority opinion now mostly views such illness as an inherited disorder. In any event, he was born too soon. In recent years, the treatment of depression has much improved.

The failure of early promise is an old story, but in Robeson's case, it was far more than personal decline, and more the hunting-down of a wounded animal. The son of an ex-slave, Robeson evoked memories of slave rebellions in the past with his mournful song of the Mississippi laborer, as did his vengeful destruction of the innocent Desdemona. His exploiters in the entertainment industry probably deserve some criticism for pushing him too far into a rebel image, and the ruthless manipulation of communist agitators during the 1930s is not a myth. So, there was really not much to prevent Senator Joseph McCarthy and his associates Cohn, Shine and Kennedy from converting the post-war fears of the nation into a circus of fearful demagoguery. Millions of people had just died in foreign wars, nations had been reduced to rubble, and vengeful heedlessness was on every side. It was not a pleasant time.

More than twenty years later, Paul Robeson died where he had been living with his sister, in West Philadelphia.

SHAKSPERE SOCIETY January 8, 2003

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, JANUARY 8, 2003

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members present: Ake, Bartlett, Bornemann, Cheston, Cramer, Di Stefano, Dobson, Dunn, Dupee, Fallon, Fisher, Green, Griffin, Ingersoll, Lehmann, Madeira, Peck, Pickering, Warden.

The Dean thanked the members of the ad hoc committee on membership for their prompt and thoughtful work. They included the Rt. Rev. Mr. Bartlett, chairman, and Messrs. Friedman, Green, Madeira, Warden, and Wheeler. Mr. Bartlett presented the committee's report. The committee considered the several emails and letters received by the Dean before their meeting in mid-December (including comment from some of the Society's most senior and most admired members). The committee's recommendations are summarized below.

First, the society might accept guidelines but should not bind itself by formal rules. Second, our goals in electing new members should be to further sociability among members and to increase the likelihood of stimulating discussions of Shakspere's plays. Third, we must be careful not to expand our membership to such a degree that the usual number attending our biweekly dinner meetings is so large that sociability is hindered. Many members feel that this number should on the average be less than twenty. Fourth (a related point), we now have forty-two "active" (dues-paying) members, and we do not wish to create a separate "inactive" category for those who can no longer attend regularly. These are further reasons why we must "be discreet about adding to our numbers."

The committee's next recommendations involved the election process. At the start of each season, the Society's officers should recommend guidelines for the year about membership needs: numbers, and. perhaps, "academic qualifications, age, diversity." At least two members should sponsor a candidate for membership, both of whom have a more than a superficial acquaintance with the prospective member. Candidates should have attended at lest two of our dinner meetings. Proposers should then seek the advice of officers as to whether and when a candidate should be proposed for election. An election should be by secret ballot; the committee recommended a two-thirds affirmative vote of those present when the vote is taken.

Vigorous discussion ensued, with comments from many members about many aspects of these recommendations, especially as to how to decide the election of a new member. Perhaps all members should be asked to vote, if they wish, for a new member, by communicating with the Dean, with notice well in advance of a final count. Perhaps three-quarters of votes cast should be needed for election. Are three or four or five negative votes sufficient to disqualify a candidate regardless of the number of affirmative votes? Given the variety of opinions expressed, Mr. Bartlett has decided to reconvene his committee to reconsider this particular issue.

The the committee recommends that before we consider other candidates for membership, we vote on the two gentlemen who were proposed for membership this fall by Messrs. Ake and Lehmann. The committee suggested that we then consider women candidates; that we elect two women when suitable candidates are proposed; and that we then declare a temporary moratorium on the election of new members, a policy to be reviewed at the start of our next season. Such a moratorium would not preclude visits to dinner meetings by guests, male or female.

More animated discussion ensued! The Dean finally proposed that all members be advised that a vote on whether women should be eligible for election to the Society will be taken at the dinner meeting of February 5, 2003. Those who cannot be present may vote by expressing their wishes to the Dean or the Secretary, by email or telephone or regular mail, before this meeting. Women will be declared eligible for election if that policy is favored by three-quarters of those who vote.

The Vice Dean introduced our first reading of Two Gentlemen of Verona in half a century. This play is written in the long tradition of literature of love stemming from the rise of courtly love in the Middle Ages. The anguished lover writes poems or letters to his beloved, telling her how he worships her and how she tortures him by her disdain even though he knows how unworthy he is of her love. The topic, and the witty treatment of the language, replete with lots of wordplays, rapid repartee in stichomythia, and both comic and serious treatment of love, remind us of other early plays of the Bard like Love's Labor's Lost and Romeo and Midsummer Night's Dream. Witty and disrespectful servants who both help and hinder lovers are frequent in this tradition of comedy from Plautus and Terence's Roman plays on. They are represented here by Speed and Lucetta. In the first act. We also meet Launce, one of Shakspere's earliest oafish farcical characters. Like Dogberry, he murders the language and cannot keep a train of thought going without tripping over both ideas and words.

In Act Two, we are in Milan, where Proteus has been forced to join his friend Valentinus and to leave behind his adored Julia. In the first scene, the servant Speed wittily (and laboriously) explains to his eager but dull master Valentinus that the beautiful Silvia avoids writing love letters to Val that might embarrass her if they were discovered; but she returns Val's love letters to her to the ardent lover, saying they are for him. Val doesn't get it; Speed patiently spells out the clever girl's compliment to her attractive but thickheaded pursuer.

We will begin reading of Two Gentlemen of Verona at Silvia's entrance in Act Two, Scene One when we next meet on January 22, 2003.

Respectfully submitted Robert G. Peck Secretary

SHAKSPERE SOCIETY January 22, 2003

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, JANUARY 22, 2003Vice Dean Fallon in the chair. Other members present: Ake, Bartlett, Binnion, Bornemann, Cramer, Friedman, Griffin, Lehmann, Madeira, Peck, Warden, Wheeler.

We remind all members of the Society that at our next meeting on February 5, a vote will be taken on whether to admit women to membership in the Society. Members who cannot be present may vote by indicating their preference to the Dean or the Secretary, by email, snail mail or telephone, before that dinner meeting. Women will be eligible for membership if three-quarters of the votes cast are in the affirmative. We will discuss other membership issues at future meetings, based on recommendations by the "Bartlett Commission.".

The Secretary wishes to thank Mr. Ingersoll, on behalf of all the members, for rediscovering a treasure trove of Society books and memorabilia in the library of the Philadelphia Club, where we held our meetings for many years. This collection includes old editions of the Bard's plays and scholarly books on Shakspere from the early and mid-twentieth century. They include Roland Frye's magisterial studies Shakespeare and Christian Doctrine and The Renaissance "Hamlet". We also have former member Alfred Harbage's Shakespeare and the Rival Traditions, given to the Society by Mrs. Harbage, presumably after Professor Harbage's death in 1976. Several of the older members of the Society, including your scribe, remember both of the Harbages with great fondness.

Most precious of the Society's volumes at the Philadelphia Club are a short history of the Society in its earliest decades, and two collections of annual dinner menus and other memorabilia from the years1856 till 1921 They are a mine of interesting information about a vanished social and cultural world. To wit: At the annual dinner in 1856, nine courses were served, and new selections of wine were served with all but the initial oysters and the final rum cake. Brandy, vintages 1800 and1820, was served before and after dinner, and three kinds of punch were served with dessert.

Evidence from other menus suggests that annual dinners in the nineteenth century began at five or five-thirty PM and adjourned at about eleven PM. Toasts were numerous, including those to bachelor members and then to "Benedick brothers"'explained by the quotation from the fifth act of Much Ado included in one menu, "Here comes Benedick, the married man." Nineteenth-century annual dinners included "Literary Exercises,"--with a long list of topics for discussion. Were these disquisitions always welcome after nine courses, seven wines, and some brandy? The quotation that accompanies one list of topics is from Bottom: "I have an exposition of sleep come upon me."

The Vice Dean introduced the discussion of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, which we began reading in the middle of Act Two, Scene One. The comic character Speed reminds us of a series of witty, even brazen servants in the Bard's plays, his speeches replete with outrageous plays on words. He is contrasted to the loutish Launce, who in Dogberry-like fashion murders the Queen's good English by ridiculous malapropisms. A member recalled a British student production of the play some twenty years ago, with the comic characters' lines spoken at great speed.

Members relished the soliloquy of Launce to his shoes, who become his parents as they bewail his departure for foreign shores'in sharp contrast to his dog Crab, who callously refuses to shed a tear (2.3).

More on comic language: The Vice Dean noted the sarcastic jibes of Valentine to his rival in loveThurio, about the verbose Thurio's "exchequer of words" without substance.

2.6'Proteus wrestles with his conscience in a long soliloquy, admitting that he is about to be unfaithful to both his lady and his best friend, but exclaiming that he cannot resist his sudden new passion for Silvia. He will tell Silvia's father of Valentine's plan to ascend to her balcony, so to speak, and steal her away that night. He villainously congratulates himself on his quick wit in thwarting his old friend'recalling later villains like Richard of Gloucester and Iago who revel in their dastardly betrayal of those who trust them.

3.1'A scene full of tediously extended speeches by Proteus, Silvia's father, and Valentine, who is made a fool of by the duke, now aware of Proteus's plan to steal Silvia from her locked room. Members commented that Shakspere learned in later plays to be much more forcefully concise and dramatically effective in such scenes. However, we remember some similarly windy speeches by Juliet's mother and father in a later play about lovers who plot to deceive the girl's parents so that she can escape their control and go off with the man she loves.

. 4.4'Launce is given another long farcical soliloquy about Crab'in language much more vivid, inventive, and entertaining than most of the blank verse in the play.

WE WILL MEET NEXT ON FEBRUARY 5 AND BEGIN READING TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA AT 4.4. 107(SILVIA'S ENTRANCE).

Respectfully submitted Robert G. Peck Secretary

SHAKSPERE SOCIETY February 5, 2003

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, FEBRUARY 5, 2003

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members present: Bartlett, Binnion, Bornemann, Cramer, Di Stefano, Dupee, Fallon, Fisher, Frye, Griffin, Hopkinson, Ingersoll, Lehmann, Madeira, O' Malley, Peck, Warden, Wheeler.

Members are grateful to Messrs. Friedman, Pope, and Madeira for hosting the 2003 Annual Dinner on the Bard's birthday, Wednesday, April 23 The probable site will be the Awbury Arboretum in Germantown.

Dr. Orville "Pete" Horwitz, a longtime member of this Society, died on January 28 at the age of 93. A memorial service will be held on February 7 at eleven AM at the Church of the Redeemer in Bryn Mawr. Senior members recalled that Dr. Horwitz had loved the Society and had attended meetings faithfully for many years. He was a veteran of the Battle of Midway, and during his Navy service in World War Two, he was awarded the Bronze Star with two oak leaf clusters. He went on to a distinguished career as a cardiologist and medical scholar in Philadelphia. He is survived by his wife of almost seventy years, Natalie, a niece of John Foster Dulles. Members grinned at memories of Dr. Horwitz's vigorous role in an annual competition among men's clubs from New York, Boston, and Philadelphia to decide whose members could tell the funniest off-color stories. Dr. Horwitz starred in this competition, borrowing stories from his Trenton barber.

Mr. Dupee recently visited our senior member, Mr. Foulke, in Florida, and brings Mr. Foulke's cordial greetings to all Society members. Mr. Dupee also reported that he has arranged, on behalf of the annual Shakspere competition among local high schools students, for Society members Fallon and Peck to play a role this year. All twenty-eight of the young people competing will be presented with copies of Dr. Fallon's recently published reader's guide to Shakspere's plays. Dr. Peck will be one of the judges of this year's contest, to be held at the Walnut Street Theater on President's Day, February 17, from 9:00 AM through the afternoon. Each of the young people, winners of contests at their respective schools, will recite a passage of some twenty lines from one of the Bard's plays, and one of Shakspere's sonnets. The winner here goes on to competition among regional winners in New York City.

Members voted on whether they favored allowing women to be eligible for membership in the Society. Several members not present had already expressed their opinions to the Secretary or the Dean. Dean Wagner announced that the final tally was eighteen votes in the affirmative, thirteen in the negative, and nine active members not voting. The motion was therefore defeated since it did not receive the support of three-quarters of those voting. Women guests are of course always welcome. A couple of members commented that we have no rules either welcoming or rejecting the candidacy of women to be members of the Society. Presumably, anyone proposed as a member, according to whatever criteria we decide on following in the future, is eligible for election. The Bartlett Committee will shortly make recommendations as to what these criteria should be.

We elected to membership in the Society Mr. Jonathan Schmalzbach, proposed as a candidate by Mr. Lehmann. We will welcome another dinner visit in the near future by Mr. Ake's friend Michael Mabry, who visited us twice in October.

We completed our reading of The Two Gentlemen of Verona in short order. We noted in Act Four that the disguised Julia analyzes her feelings about her perfidious lover Proteus at some length; she prefigures articulate psychologists of love in Shakspere's later and better romantic plays. Julia and Silvia are by far the most vigorous and strong-minded characters in this weak play, suggesting Rosalind and Juliet and Viola and Olivia, and even, perhaps, Desdemona, in later masterpieces about conflicted love. In Act Five, we visit the forest, so often a symbolically important setting for scenes in the Bard's plays of love, as in Midsummer Night's Dream and As You Like It. Strong emotions cause turmoil but are reordered after threats to lovers' happiness.

WE MEET NEXT ON FEBRUARY 19, 2003, WHEN WE WILL BEGIN READING THE TAMING OF THE SHREW.

Respectfully submitted Robert G. Peck Secretary

SHAKSPERE SOCIETY March 5, 2003

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members present Ake, Bornemann, Fallon, Friedman, Hopkinson, Ingersoll, Lehmann, Madeira, O' Malley, Peck, Pickering, Pope, Schmalzbach, Warden.

Mr. Ake said a few eloquent words on behalf of his friend Michael Mabry, whom he proposed for membership in the Society. Mr. Mabry was elected by unanimous vote of the members present.

Members were reminded that two Shakspere productions can now be seen in town: Macbeth at the Shakespeare Festival theater at 21st and Sansom Streets (until April 13) and Twelfth Night at the Arden Theatre on Second Street next to Christ Church (also until April 13). Forthcoming: the Lantern Theater, in the alley next to St. Stephen's Church on Tenth Street just south of Market, will stage The Tempest from March 28 thru May 4. The Shakspere Festival and Lantern tickets are usually inexpensive. All these theaters draw on the the same pool of very talented local actors who have made careers here recently (the Arden also imports occasionally'usually terrific people).

The Dean announced that at our next meeting on March 19, we will discuss which plays of the Bard we will read at next season's meetings. Members on the secretary 's email list now have a memorandum of plays not read within the past eight years, with dates when each play was the last read. For members who cannot receive email, your scribe will add that Winter's Tale was last read in 1989, Romeo and Troilus in 1991 and As You Like It and Macbeth in 1992. Among minor plays: Timon 1953, Cymbeline 1962, All's Well 1975.

We began reading The Taming of the Shrew in the middle of Act Two, Scene One, Kate and Petruchio's first scene together. The Vice Dean commented that we begin to see here Petruchio's strategies for taming Kate, which is various. First he "establishes control" by calling her over and over by her familiar nickname, despite her prim but vigorous demand that he call her Katharine. He physically manhandles her, too, as he does later as well; meanwhile, he repeats a series of harsh judgments he has heard about her character, loudly proclaiming that in fact, she is lovable, sweet, companionable.

Members wondered whether Petruchio's motives for pursuing Kate were exclusively mercenary. He boasts to his listeners at one point about the enormous riches that his father has left him. Is he primarily drawn to the task of wooing Kate by the psychological challenge, the test of his virile prowess in conquering such a famous vixen? The Vice Dean pointed to the bizarre, embarrassingly ugly and even tattered costume that Petruchio wears on his wedding day (Act Three, Scene Two) as evidence that he means to humiliate the proud Kate, another of his strategies for taming her. He refers to her as "my goods, my chattels," reminding us that in Shakspere's day, an Englishwoman usually had to give up all of her property to her husband when she married, and she was expected to obey him in all things. He will not allow Kate to stay for the wedding feast, despite her temper tantrum: "Nay, look not big, nor stamp nor stare nor fret;/I will be master of what is my own."

In Act Four, Scene One, we see Petruchio "wearing Kate down," as the Vice Dean commented: he allows her no food on the long trip to his estate; he makes sure that she is dumped in the mud with her horse on top of her; he again refuses her food at his house, on the the pretext that the cook has burnt the joint, and he keeps her up all night, not in marriage-night frolicking but by repeated temper tantrums of his own. At the scene's the end, Petruchio makes his only speak directly to the the audience, calling her a falcon who can only be tamed by strong measures, and declaring, "And thus I'll cure her mad and headstrong humor./ He that knows better how to shame a shrew,/ Now let him speak, it is a charity to shew." Her disease, an imbalance of the humor, must be cured by drastic doctoring to make her fit to live with, a woman he can love.

Mr. Bartlett has just sent the Secretary a statement of the admissions committee's recommendations, to form the basis of discussion among the members. The Secretary will pass this information along to members very shortly.

WE WILL MEET NEXT ON MARCH 19, 2003, AND BEGIN READING THE TAMING OF THE SHREW AT THE BEGINNING OF ACT FOUR, SCENE TWO.

Respectfully submitted Robert G. Peck Secretary

SHAKSPERE SOCIETY March 19, 2003

MEETING OF THE SHAKSPERE SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA AT THE FRANKLIN INN CLUB, MARCH 19, 2003

Dean Wagner in the chair. Other members present: Ake, Bartlett, Bornemann, Cheston, Cramer, Dunn, Fallon, Griffin, Hanna, Hopkinson, Ingersoll, Lehmann, Mabry, Peck, Pope, Schmalzbach, Warden.

The Dean wondered whether we should make a point of avoiding dinner meetings on Ash Wednesday, which we do not schedule as a meeting date most seasons. The collective feeling was that this was not an issue that concerned most members. Those who feel strongly should contact the Dean.

The Rt. Rev. Mr. Bartlett summarized the report of his membership committee, stressing that their recommendations were guidelines, not rigid rules binding the Society's hands. We should take care not to expand membership much beyond our present numbers since a fairly small number at dinners enhances comradeship or so many feels. We encourage visits by guests as a source of enrichment of our discussions, but without suggesting to visitors that they might become members.

When a candidate for membership is to be voted on, the Secretary will notify all members well ahead of the meeting at which a vote is to take place. The candidate will have both a sponsor and a seconder, and the sponsor will make sure that several members have had a chance to get to know the candidate better than one can by a quick exchange of pleasantries over the cheese before dinner. Voting will be by written messages sent to the Dean before the dinner of the vote, and by written vote at the dinner meeting when the vote is held. The election will be by a majority of those voting, which will include affirmative votes by at least fifteen members.

It was agreed that it would be in the best interests of the Society to seek out Shakspere lovers with academic expertise in English Renaissance studies as potential candidates for membership.

The Dean recommended, after hearing from a number of members about the issue of the plays to be read next season, that in 2003-2004, we read Macbeth and As You Like It, with perhaps two meetings in the middle of the season devoted to scenes from Timon of Athens, which the Society has not read in fifty years. Members present cordially agreed with this plan.