2 Volumes

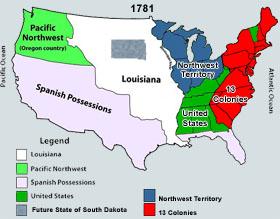

Constitutional Era

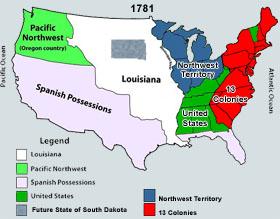

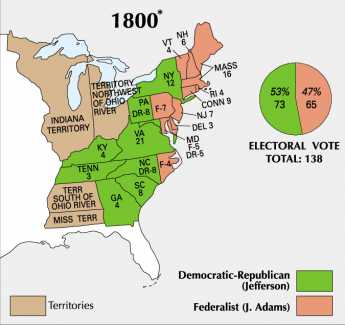

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Foreign Affairs

This topic is under construction. Feel free to watch it evolve.

Emails From Iraq (1)

An American contractor on his arrival in Iraq in 2007 to work for a company with a contract to mentor small businesses owned by Iraqis

|

Did you know you can still get commercial flights into Iraq? And did you know the politically correct way to land an airplane in Baghdad ends with a flush ... an extremely steep, downward spiral from 15,000 feet directly over the airport so not to attract gunfire? We flew Royal Jordanian Airlines so ours was a royal flush. Welcome to Iraq!

Some of you joined me from Almaty to Zagreb, from Bishkek to Banja Luka and Bansk. But nothing, absolutely nothing, compares with Iraq. I cannot do justice after only a few days, but my objective is to give you a first person, on-the-ground perspective of this country. At the very least, this will be educational. I fully expect my opinions to change and stories to conflict, but that's the way things are: fluid and unpredictable. I also expect and hope that what I tell you will differ vastly from what you are seeing on the US news. We all know of the US bias; these reports will give you perspective on the biases. Truth is a matter of interpretation and yours is as good as anyone's.

There are things I cannot say much about, mostly to do with security. What I suggest if you think of the most exciting action film you ever saw and begin there. My daily gear includes an armored vest and helmet, and moving from point A to point B requires extensive planning and preparation, including multiple guards and armored vehicles. I am learning to follow orders which will be a pleasant surprise to my wife. For the ladies, this is a haven of hunks: young, dashing men in excellent physical condition.

My story starts in neighboring Amman, Jordan, a diamond in the ruff, a rose among thorns. People walk the streets of Amman as if things are normal. If you look at a map, however, you will see Jordan is surrounded by lands where walking streets is not a privilege taken lightly. Our stay here is brief, overnight only. In the morning we board a plane for Baghdad but are instructed to go back to waiting because of "bad weather" in Baghdad, the first sign of unpredictability. Later, after flying over a sand storm on the way to Baghdad (it is mostly desert between Amman and Baghdad) and finding beautiful weather upon arrival, we are unsure what the real cause of the delay was.

After more delays in passport control (one of our party was deported back to Amman because he did not have the right paperwork), the other member of my team and I met our security detail, a guy from France and another from Australia, and we donned protective gear and received a briefing about what we could expect on our five-mile trip from the airport to the International Zone (IZ, formerly called the Green Zone). This stretch of highway has been called the 'most dangerous road in the world' and our security personnel is accustomed to navigating assorted threats. The ride was directly from the movies and we arrived, as expected, safely.

I haven't said much about my job because it is not entirely clear to me. I am a civilian contractor, and working for the US government requires skills nobody should ever seek. I'll fill you in as this unfolds. By the way, I turned a huge corner today. Boarding an airplane to Iraq for the first time produces anxiety by itself. Knowing you will spiral steeply toward a target is equally troubling, not just because of the dangerous maneuver but also because of the reason for it. So as I nestled fitfully into my seat and tugged the seatbelt tighter than usual, and only then learned the pilot was a woman, I had two choices. The choice I made was to refresh my amazement of the 'fairer' gender. It seems women really can do anything!

Feel free to contact me if you want to give me orders. I am listening very well right now.

Eisenhower, Reagan and Rumsfeld

|

| Donald Rumsfeld |

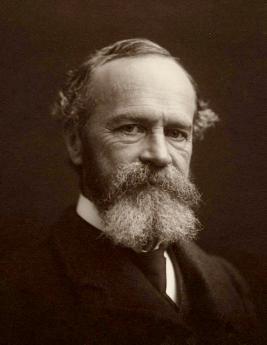

At the moment, the coherence of the motives of Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, and the retired military officers who united in denouncing him can only be dimly imagined. At best, we can expect future revelations to tell us how close we came to the truth. But let's take a stab at it.

|

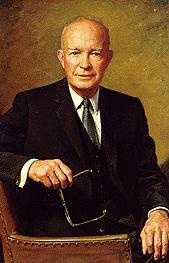

| President Eisenhower |

More than fifty years ago, President Eisenhower baffled most of us by warning about the Industrial-Military Complex, which we now see about like this: military contracts are awarded for future weapon development in the civilian sector. This system was first devised in 19th Century Germany, with great success in providing the German High Command with new weapons and methods of warfare which three times brought Germany close to conquering Europe. No doubt, many of the more intellectual officers of the military had dreams and fantasies which translated into Requests for Proposals. No doubt, some scientists brought ideas of workable research projects into receptive military conferences. It's hard to say where such a process begins, so it's fair to call it a Complex.

Although we fought some moderate-sized wars during the period from Eisenhower to the end of Reagan's second term, there's a short-hand way of describing the Industrial Military Complex during that time: we devised a regular succession of new weapon systems, all of which we hoped we would never use, some of which we had little intention of using. The poster example was Star Wars, the threat of which caused the the Soviet Union to surrender the Cold War when in all probability Star Wars was a project that didn't even work. Never mind the oversimplification; this will suffice as a framework for a different proposition.

|

| Weapons System |

The spin-offs from this military research underlie the sudden flowering of peaceful products from Silicon Valley, and the suburbs of Houston and Boston. Japan, mandated to avoid military development, was particularly active in developing peaceful spin-offs from new technology. Over in the world of the professional American military, the spin-offs were somewhat different. Each new technology needed to be carried forward into what was called a weapons system, where whole industries were shaped around the idea of mass-producing it, and regiments of young officers planned their future careers as the spear-heads of the new advance in warfare. And then, as often as not, the weapon system was totally dropped in favor of some newer weapon concept, with new industries to profit from its production and new officers to promote their careers as the leaders. It was a great system for the research industry, but it was hard on its supporters and disciples.

|

| Al Queda |

Meanwhile, there were two other negative responses. Military leaders in the underdeveloped world began to imagine their masses of troops and low-technology style might be able to win wars of attrition against a more sophisticated enemy, and in turn the North Koreans, the Vietnamese, and Al Queda taught us some unexpected lessons. The American military was not asleep, we made short work of the same Afghans who had nearly bled the Russians to death. These constant reminders that the world remains a dangerous place exposed two major weaknesses in the system of devising new styles of warfare. You can't be really sure it works until you try it with live ammunition on a serious enemy, and you can't be sure you can sustain an occupation of a defeated enemy's territory without boots on the ground.

So the little wars in Afghanistan and Iraq tested the new systems for weaknesses to be corrected, and identified weapon systems which ought to be expanded for more serious wars somewhat to the East. You hate to believe our leaders are thinking this way, but there's no doubt we would blame them if they hadn't identified Humvee's need more side armor, body armor's need for more ventilation, that the CIA needs more language experts. Military robots are attractive ideas, but they still require a desperate enemy to search out their weaknesses.

On one level, of course, all of this is terribly plausible. On another level, soldiers are getting killed by it. It is certainly easy to sympathize with officers who had been trained to fight the old way, the tried and tested one. Or with others who had staked their whole future career on the potential of a weapon system which was never adopted. It's easy to believe your pet project was an unsuccessful contender for reasons of local or partisan politics, more bitter still when you see plain evidence that was true. And particularly when the top civilian leader did not come through the same cultural conditioning of the military academies. It must have been particularly frustrating for academy graduates to encounter a Princeton man who was described by Henry Kissinger as the most effective bureaucratic infighter he had ever met. On his second tour at the job of Secretary of Defense, nearing the end of his term. It upset all of the stereotypes of the tribe.

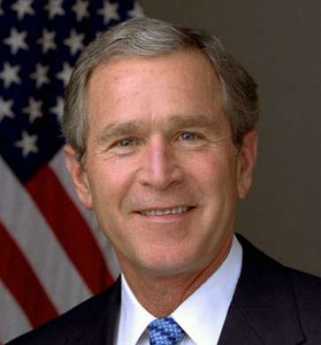

Let's look at this infighting in a larger sense. Although the professional military would undoubtedly express offense at being described as just part of the bureaucracy, it can sometimes be useful to consider them as such. George W. Bush came into the Presidency muttering that one way to control the bureaucracy was to starve them to death; reduce the taxable income of the government, and inevitably the size of the government structure would have to shrink. Since in fact, he allowed the federal budget to grow, it can be argued his talk of starving the government into shrinking was just a bluff. But the bureaucrats weren't so sure it was a bluff; this guy seemed to march to a different drummer. The lower orders of the bureaucracy have considerable pride in their work, which is undoubtedly superior to what prevails in state government. The upper echelons secretly believe they are smarter and better educated than their political bosses, and like the English civil service, retreat into the "Yes, minister" mode of self-defense. All of this career anxiety is threatened by a President who openly speaks of starving the government into a smaller size. And while there are many major differences between the professional military and the professional bureaucracy, on this point they are just about the same. Nevertheless, the country cannot stand by and permit open insubordination or the overthrow of political control by the civil service. Maybe the civil service really is getting a little too big.

CEO of the World

|

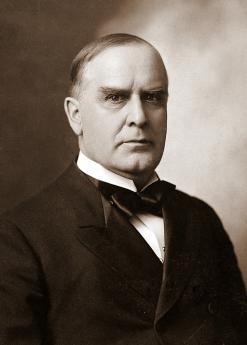

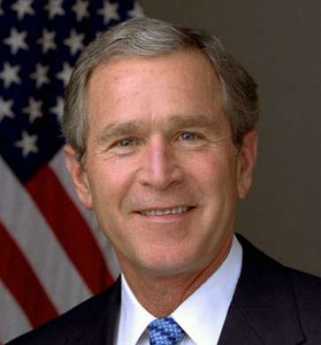

| George W Bush |

Christmas, 2005.

My Quaker Friends are comfortable with the firm position that no war can be justified. This sometimes leads to feeling it's unnecessary even to consider the justifications or the mitigating circumstances of any war, since nothing can be said which will lessen their opposition. My Democrat friends seem to have an equally closed mind, one which leads them to emotional denunciations of George Bush which I know cannot be completely reasonable. However, George Bush and I went to the same sort of schools, feel passionate about the same sort of libertarian economics. I like his father very much, even though our association in the same college class was very brief. In short, I want to give this man every benefit of doubt and fairness, even in the face of what I must acknowledge to Quakers and Democrats is a glum recognition of the strength of their strongest argument. I don't like wars, I don't like political spin. But it is important to me to feel I am doing my own thinking, so I resolved to make as good a case for Was I possibly could. After that, perhaps I could take time to see how well I had convinced myself.

|

We frequently hear that America is the only superpower in the world; our president is the most powerful man alive. I suspect George Bush believes that, too. His formulation is likely to be that he has found himself the Chief Executive, the CEO, of the world. His training and background tell him how to manage a huge enterprise: delegate authority. That is, assign general goals to subordinates. Prior to 1918, an American president would assign foreign affairs to his State Department.

Our involvement in several cataclysmic wars made clear that large portions of the world would not leave us alone, nor respond to the persuasiveness of diplomats, either. Certain governments at certain times, would have to be assigned to the Department of Defense. This technique worked even better than we expected; Germany, Japan, and Italy became our most effective allies.

|

| Baltic States |

The rest of the non-American World was turned over to the multi-national corporations. More accurately, perhaps, the multinationals took the rest of the world away from the State Department and proceeded to subdue a great deal of it. South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Poland, the Baltic states, Hungary, India, the Czech Republic seemed to do it eagerly, China did it in its own way, and much of the rest did it grudgingly. Russia and mainland China, along with Canada and Mexico, are special cases. Perhaps an interdisciplinary approach needs to be devised for them.

<But by the time the younger Bush President came to power, it had become clear that none of our approaches, diplomatic, military or economic, would make much difference to a large subcivilized part of the world. Africa and vast stretches of Central Asia were just about the same as they were in 1900. Like South America, it looked as though they could be safely ignored -- until the events of September 11 showed that they could not be. Furthermore, it was clear to the American government that this disaffected region not only hated us, but had the capability of making atom bombs, and the oil revenues to finance a very destructive war against civilization. In Texas parlance, it's them or us.

The largely marginalized State Department quite properly responded to the enraged vigilante police action by protesting that you can't intimidate millions of people who essentially have nothing to lose. The diplomatic corps has long been a creature of a handful of universities who were once themselves captured by sit-ins and more recently by tenure.

Second Amendment: The 28th Infantry Division

SINCE the nation was only formed in 1776, and the only memorable war before that was the French and Indian War of 1754, the origin in 1747 of the Pennsylvania 28th Division of Infantry needs a little explaining. The 28th is a National Guard reserve unit, taking its present organizational form 138 years ago. Even counting from that moment makes it the oldest (and third largest) division in the Army, but another 123 years of history stretch back before that.

AMENDMENT II A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

|

| Second Amendment |

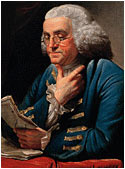

A few people remember that Ben Franklin made his first step into politics during King George's War (1744-48), when French and Spanish privateers were suddenly roaming Delaware Bay . The pacifist Quaker government hesitated in confusion, so Franklin stepped forward to call for a volunteer militia. It was paid for with a lottery because the Quaker legislature resisted; there seemingly was no end to Franklin's ingenuity. The unit remained a permanent one, and since then served with distinction in the various conflicts through the Civil War, when it was organized into the National Guard. The volunteer movement it inspired was part of the impetus for the Second Amendment to the Constitution which the National Rifle Association will be glad to explain to you, although historians commonly trace the civilian soldier tradition back to King James and the English Civil War. Franklin was unfailingly patriotic, and never hesitated about military measures when they seemed necessary. He lived long enough so his military sympathies were still a dominant force at the Constitutional Convention, more than forty years later.

Major General Wesley E. Craig Jr., former commander of the Division, was kind enough to address the Right Angle Club about the 28th Division recently. Since the citizen soldiers of the National Guard all have other careers, his daytime job was as an executive for Strawbridge and Clothier. A moment of reflection about the Scottish origin of his own name, connected with a strongly Quaker firm, evokes the two strongest social and ethnic tensions of early Pennsylvania history.

The audience was treated to a description of the military history of the unit, whose largest battle was the Battle of the Bulge in World War II. But they are in Iraq today, with almost every soldier having served one tour of duty, many of them two or even more. They were the unit stationed in El Ambar province during the period before the Sheiks finally decided that America was going to win this war, and changed sides. General Craig had returned to America only a month before this famous turning-point. Before that, units of the 28th were in Bosnia and Kosovo, and are proud to have been chosen for the introduction of many innovative technologies. They are the only reserve division with Stryker vehicles, and before that employed unmanned drone aircraft for reconnaissance. Observer drones fly at 2000 feet and carry no weapons, unlike the Predator drones which carry rockets and fly at 10,000 feet.

Not everything is a story of combat action; the 28th Division is very proud of its activities in the Katrina rescue missions and other domestic emergencies. The Go Ahead Division is proud of its reputation for being on time, every time.

And it is mindful of the sad side. In Iraq, it is 31 KIA, with 167 WIA. If you're uncertain what that means, try a little harder.

Franklin: Upstart Hero of King George's War (1747)

In 1747, Benjamin Franklin had a life-transforming experience, acting quite unlike his character before, or later. At that time, Old Europe was engaged in some distant tribal skirmishing which has come to be known as King George's War. King George II, that is, under whose rule Franklin in 1751 inscribed on the cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital that Pennsylvania was flourishing, "for he sought the happiness of his people."

|

|

The cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital inscribed by Franklin. |

Those distant commotions suddenly developed a harsh reality for the little pacifist sanctuaries on the Delaware River, when French and Spanish privateers suddenly raided and destroyed settlements on Delaware Bay. The Quaker Assemblies and their absentee Proprietor merely dithered and huddled in the face of what impended as a totally unexpected threat of annihilation of the pacifist colonies. It probably only seemed natural for the owner of the largest newspaper in the colony to publish a pamphlet called "Plain Truth," urging the inhabitants to rally to their own defense, and pressure their government to lead them. The Quaker leaders were in fact unable to readjust a lifetime of pacifist belief in a few days of an emergency, and the English Proprietor, then Thomas Penn, was far too remote to take active charge of matters. So, Franklin gave speeches, also an unfamiliar role for him, and finally brought out a detailed proposal for the creation of a Pennsylvania Militia. Ten thousand volunteers promptly signed up, elected Franklin as their Colonel; but he declined, and served as a common soldier.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in 1767. |

Against naval attack, the Militia needed cannon, which did not exist in the colony. So Franklin organized a lottery, raised three thousand pounds, and tried to buy cannon from Governor Clinton of New York. New York declined to sell, and so Franklin led a delegation to New York to negotiate. The negotiations largely consisted of getting Governor Clinton drunk and convivial, but they were successful, the artillery was shipped off to Philadelphia. Although they were undoubtedly grateful to Franklin for saving the day, this entirely extra-legal recruitment of an army badly rattled the Quakers and their Proprietor, since it demonstrated the ineffectiveness of their governance at a time of obvious crisis, and might ultimately have led to their overthrow. Franklin's heroic behavior seemed so threatening to Thomas Penn that he described him as "a dangerous man," acting like "the Tribune of the People."

When the underlying commotion in Old Europe subsided, the threat to the colonies disappeared, so the Militia disbanded in a year. Franklin seemed to be just as uncomfortable with his unaccustomed role as the governing leaders were, and he hardly ever mentioned it again. However, this is the sort of reflex leadership which makes political careers, and it surely influenced his decision to retire from business in 1748, run for election to the Assembly, and live like a gentleman. Seven years later, during the French and Indian War, he had become the chosen leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly, had much longer to think through what he was doing, and had learned how to organize a war. By that time, as the saying goes, he knew who he was. He was a man whose silent memories could flashback to that time when a bald fat printer stepped out of the crowd, saying "Follow me," and ten thousand men with muskets did so.

Franklin's Admirers on TV

|

| Brian Lamb |

There are now three channels of C-span, continuous cable television programs about the influence of history on current problems. Sessions of Congress and its committees, the speeches of the President, political campaigns, are shown as they happen. But interviews and book reviews are shown in parallel, with an opportunity to go into the archives and organize originally unrelated programs into seminars on a current topic. The editor, Brian Lamb, has a light hand and considerable impartiality. But he's there, all right, organizing blogs into topics just as Philadelphia Reflections tries to do.

|

| Friends Select School |

This similarity of design had been floating around for some time, but it suddenly came into focus when I recognized myself in the front row of an audience on C-span, listening to Edmond S. Morgan talking at the Friends Select School about his new book on Benjamin Franklin, a few months earlier. Thank goodness I bought a book and had it autographed because the filming had been so unobtrusive I hadn't noticed it at the time. I clearly need to have haircuts more frequently. Professor Morgan's parting words that evening had stayed with me, "Franklin doesn't tell you everything about himself, but what he tells you -- is straight." That's quite a compliment from the editor of 47 volumes of Franklin's work.

|

| Walter Isaacson |

Grouped with this tv portrayal of me as a groupie were interviews with Walter Isaacson and some other Franklin biographers, taken at other times and placing focus on other aspects. Here again, more insights emerged from quickly considered replies to audience questions than from the prepared speeches. Replies to questions from the audience are more in a class with blogs, anyway. Whenever you get all of the adjectives and qualifications polished, you sometimes don't say what you mean. Perhaps that last comment can be rearranged to say that answering audience questions occasionally leads to blurting out precisely what you mean.

And so, two unrelated audience answers need to be linked. A question about Franklin's love life caused Isaacson to refer to Franklin as a lifelong seducer. From the unknown mother of his illegitimate son William, to the simultaneous flirtations with two famous French ladies that took place when he was an octogenarian, and not overlooking several other affairs with Cathy Green and Polly Stevenson and allusions to others, Franklin was obviously an accomplished seducer in the full meaning of the term. It is thus legitimate to suspect the techniques of seduction at work in many of his public projects, from starting the Library Company to persuading the French to help the Revolution. He discovered late in life what many have discovered about the life of a diplomat, and quickly recognized that he was already pretty good at what that seemed to entail. Let's slide to a slightly different application of that idea.

|

| Benjamin Franklin and French Women |

By the accident of hostess seating arrangement, I found myself seated next to two historians from Harvard, and somehow it came out that one of them felt that Franklin loved the French. Simply loved them. Somehow that didn't sound quite right when compared with Franklin's early years of mobilizing Pennsylvania to fight the French, starting the first National Guard militia unit to defend Philadelphia against French raiders, supporting General Braddock's expedition with his own money, urging the British government to sweep the French from Canada, and working most of his life to assemble the colonies and Great Britain into one world-dominating entity. It's true that 18th Century France was at the peak of scientific achievement, and Franklin the inventor of electricity was quickly taken in by the European scientific community, but that's scarcely the same thing as loving France. Louis XVI was in fact quite annoyed by all the attention Franklin was receiving. And so the scholar on TV went on to say that correspondence had been discovered in which Franklin quite casually remarked that during the Continental Congress he had strongly argued that America should stand alone and have no European allies. Congress it seems overruled him, so he dutifully set sail for France to seduce them.

We come to another chance social encounter. On a recent trip to Paris, the GIC had taken along as a speaker, no less than a member of the Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, a Governor of a Federal Reserve District, to speak about the threat of inflation and currency crisis. In time, our French hosts invited us to look at some documents of interest, like the Louisiana Purchase. Lying on the table was the original treaty between America and France, signed by B. Franklin. The Federal Reserve governor, making small talk, observed that Franklin sweet-talked the French into loaning America too much money, eventually leading to their bankruptcy. As I recall, my rejoinder was, "Well, just print some more paper money, right?" It was intended to be a jocular remark, but it somehow didn't seem to be taken as such.

Mercantilism Dies Hard

|

| Mercantilism to Americans |

Whatever mercantilism was supposed to mean can be debated by captive college students; mercantilism to Americans is and was just a bad thing having to do with economics, mentioned only when the speaker is searching for an epithet. Our present understanding of the mercantilist term is that brutal government action, even war, was employed to benefit favored citizen merchants, while the economics of a whole nation of consumers was subverted toward enhancing state power. All of this rapacity was for the betterment of one nation at the expense of its neighbors, and at the expense of its colonies. The surprisingly vague but more modern term of fascism is often substituted, to denote evil uses of government to promote the interest of combined military and industrial elite, to the general disadvantage of everyone else. Because so many opponents of mercantilism were upset about specific forms of mercantilist activity, Adam Smith is associated with the idea that mercantilism was the opposite of international free trade, and the American founding father are associated with the idea that mercantilism embodied everything we disliked about colonialism. Some prominent 18th Century leaders constructed a body of theory to defend mercantilism and firmly established the idea that the whole approach was founded on long-discredited sophistry. In recent times, the only reputable economist to defend parts of mercantilism was John Maynard Keynes, who approved of the idea of emphasizing third-world exports in order to assist developing countries into a modern economy. Whatever is the underlying idea behind this mercantilist idea that has caused so much trouble, and includes so many disconnected features?

Allow an amateur theory. In my view the fundamental misconception underlying mercantilism was the idea that economic relations between individuals and nations are a zero-sum game; what I gain must be at the expense of someone else's loss. Almost every child believes that many or even most everyday transactions seem to confirm it, and vast multitudes of mankind believe it to the end of their days. But as part of the Industrial Revolution, the counter-intuitive realization began to spread that cooperative behavior, within limits, could sometimes result in all participants becoming better off, harming no one. Perhaps it was even a universal idea. Adam Smith popularized the idea that when two parties freely participate in the free trade of a marketplace, each one can come away from the trade feeling better off; one party would rather have the goods, the other party would rather have the money, and they trade. Multiplied millions of times, the expansion of free trade would enrich whole nations, even the whole world. George Washington may not have understood all that, but he did know that England was injuring him with rules about insisting British subjects must conduct all foreign trade in British sailing vessels, must not manufacture locally, must do this, must not do that.

Exporting was good, importing was bad, manufacturing was to be concentrated in the mother country, consuming was to be discouraged -- what was the unifying theory behind all this? It would seem to have been the gold standard. Gold was durable, and its supply was limited. It had certain undeniable advantages, but its overall effect was to restrain industrial progress. If the economy is constantly expanding, but the supply of gold is relatively limited, the price or value of everything will go steadily down over time. In George Washington's time that was particularly irksome with regard to the value of his plantation, and his vast land holdings of Ohio land. It was also true of everything else that was reasonably durable. If everything is measured in gold, and gold is limited, then the accumulation of gold is ultimately the only way to accumulate wealth. The English nobility who were profiting from the system might not perceive it, but the colonists could perceive it in their bones. Small wonder that modern banking, economics and innovative finance took root in the American colonies. If not first, at least most vigorously. Small wonder we had a revolution men would die for, while the British were merely annoyed and mystified.

Vast areas of Asia, Africa and the Middle East are still committed to the idea that the only way to get rich is to steal from others; since everyone wants to get rich, everyone steals. Someone has reduced this idea to a simple game theory called the Prisoner's Choice. If two prisoners tattle on each other, both will be severely punished. If both prisoners refuse to testify, both will go free. If one tattles and the other remains mum, the tattler will go free and the loyal comrade will get hanged. Reduced to its simplest level in a series of repeated games, the theory states that it's better for everybody to cooperate most of the time, but you must be willing to play tit for tat if the other party cheats. Be cooperative as much as you can, but never forget to wallop a cheater, and then forgive him later so he can have a chance to play nice. Lots of people will think you are a sucker if you play nice, so, unfortunately, it is necessary to retaliate -- swiftly and painfully -- when someone cheats. Centuries of American history are explainable with this simple game theory.

And not just with tribesmen and Nazis. When Winston Churchill finally realized that the Bretton Woods Conference was going to mean the end of the British Empire, he was almost tearfully plaintive with his friend Frank Roosevelt, but he said he understood.

And six years later, when Churchill's protege Anthony Eden invaded Egypt over the Suez Canal, Dwight Eisenhower the hero of the Normandy Invasion that saved England, suddenly turned nasty. England would immediately abandon that invasion, or Eisenhower would foreclose on British debts and ruin them.

That was the end of British colonialism, and in a sense, it was the final end of the Revolutionary War.

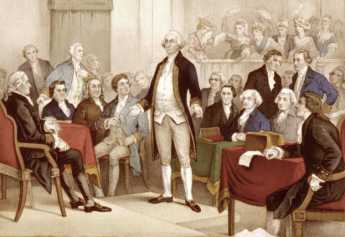

Designing the Convention

|

| The Convention and the Continent |

THE prevailing notion of the Constitutional Convention once depicted James Madison as seized with the idea of a merger of former colonies into a nation, subsequently selling that concept to George Washington. The General, by this account, was known to be humiliated by the way the Continental Congress mistreated his troops with worthless pay. But recent scholarship emphasizes that Washington noticed Madison in Congress becoming impassioned for raising taxes to pay the troops, was pleased, and reached out to the younger man as his agent. Madison seemed a skillful legislator; many other patriots had been disappointed with the government they had sacrificed to create, but Madison actually led protests within Congress itself. A full generation younger than the General and not at all charismatic, Madison's political effectiveness particularly attracted Washington's attention to him as a skillful manager of committees and legislatures. Washington was upset by Shay's Rebellion in western Massachusetts, which threatened to topple the Massachusetts government, but Shay's frontier disorder was only one example of general restlessness. There was a long background of repeated Indian rebellions in the southern region between Tennessee and Florida, coupled with uneasiness about what France and England were still planning to do to each other in North America. It looked to Washington as though the Articles of Confederation had left the new nation unable to maintain order along thousands of miles of the western frontier. The British clearly seemed reluctant to give up their frontier forts as agreed by the Treaty of Paris, and very likely they were arming and agitating their former Indian allies. Innately rebellious Scotch-Irish, the dominant new settlers of the frontier, were threatening to set up their own government if the American one was too feeble to defend them from the Indians. The Indians for their part were coming to recognize that the former colonies were too weak to keep their promises. With the American Army scattered and nursing its grievances, the sacrifices of eight years of war looked to be in peril.

The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured ... by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was "to form a more perfect Union.

|

| A.Lincoln, First Inaugural |

Even Washington's loyal friends were getting out of hand; Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris had cooked up the Newburgh cabal, hoping to provoke a military coup -- and a monarchy. Because they surely wanted Washington to be the new King, he could not exactly hate them for it. But it was not at all what he had in mind, and they were too prominent to be ignored. So he had to turn away from his closest advisers toward someone of ability but less stature and thus more likely to be obedient. It alarmed Washington that republican government might be discredited, leaving only a choice between a King and anarchy. Particularly when he reviewed shabby behavior becoming characteristic of state legislatures, something had to be done about a system which proclaimed states to be the ultimate source of sovereignty. Washington decided to get matters started, using Madison as his agent. If things went badly he could save his own prestige for other proposals, and Madison could scarcely defy him as Hamilton surely would. Washington could not afford to lose the support of the two Morrises, and still, expect to accomplish anything major. Madison had been to college and could fill in some of the details; Washington merely knew he wanted a stable government and he did not, he definitely did not, want a king. Many have since asked why he renounced being King so violently; it seems likely he was projecting a public rejection of the Hamilton/Morris concept in a way that did not attack them for proposing it. It was a somewhat awkward maneuver, and to some degree, it backfired and trapped him. But Madison proved a good choice for the role, and things worked out reasonably well for the first few years.

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the Federal Government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State Governments are numerous and indefinite.

|

| J.Madison, Federalist#45 |

Madison was young, vigorous and effective; he held the widespread perception of the Articles of Confederation as the source of the difficulty, and he was a reasonably close neighbor. He was active in Virginia politics at a time when Virginia held defensible claims to what would eventually become nine states. Negotiations for the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 would be going on while the Constitutional Convention was in session, and Virginia was central to both discussions. After conversations at Mount Vernon, a plan was devised and put into action. Washington wanted a central government, strong enough to energize the new nation, but stopping short of a monarchy or military dictatorship. There were other things to expect from a good central government, but it was not initially useful to provoke quarrels. Madison had read many books, knew about details. Between them, these two friendly schemers narrowly convinced the country to go along. As things turned out, issues set aside for later eventually destroyed the friendship between Washington and Madison. Worse still, after seventy years the poorly resolved conflict between national unity and local independence provoked a civil war. Even for a century after that, periodic re-argument of which powers needed to revert to the states, which ones needed to migrate further toward central control, continued to roil a deliberately divided governance.

|

| Constitutional Convention |

For immediate purposes, the central problem for the Virginia collaborators was to persuade thirteen state legislatures to give up power for the common good. The Articles of Confederation required unanimous consent of the states for amendment. To pay lip-service to this obstacle, it would be useful to convene a small Constitutional Convention of newly-selected but eminent delegates, rather than face dozens of amendments tip-toeing through the Articles of Confederation, avoiding innumerable traps set by the more numerous Legislatures. In writing the Articles of Confederation, John Dickinson had been a loyal, skillful lawyer acting for his clients. They said Make it Perpetual, and he nearly succeeded. The chosen approach to modification was first to empower eminent leaders without political ambitions and thus, more willing to consent to the loss of power at a local level. Eventual ratification of the final result by the legislatures was definitely unavoidable, but to seek that consent at the end of a process was far preferable because the conciliations could be offered alongside the bitter pills. Divided and quarrelsome states would be at a disadvantage in resisting a finished document which had already anticipated and defused legitimate objections and was the handiwork of a blue-ribbon convention of prominent citizens and heroes. By this strategy, Washington and Madison took advantage of the sad fact that legislatures revert toward mediocrity, as eminent citizens experience its monotonous routine and decline to participate further in it, but will make the required effort for briefly glamorous adventures. Eminently successful citizens are somewhat over-qualified for the job, whose difficulties lesser time-servers are therefore motivated to exaggerate. To use modern parlance, framing the debate sometimes requires changing the debaters. In fact, although he had mainly initiated the movement, Washington refused to participate or endorse it publicly until he was confident the convention would be composed of the most prominent men of the nation. This venture had to be successful, or else he would save his prestige for something with more promise. Making it all work was a task for Madison and Hamilton, who would be replaced if it failed.

|

| John Dickinson |

While details were better left hazy, the broad outline of a new proposal had to appeal to almost everyone. Since the new Constitution was intended to shift power from the states to the national government, it was vital for voting power in the national legislature to reflect districts of equal population size, selected directly by popular elections. That was what the Articles of Confederation prescribed. But no appointments by state legislatures, please. In the convention, it became evident that small states would fear being controlled by large ones through almost any arrangement at all. On the other hand, small states were particularly anxious to be defended by a strong national army and navy, which requires a large population size. England, France, and Spain were stated to be the main fear, but small states feared big neighboring states, too. Since the Constitutional convention voted as states, small states were already in the strongest voting position they could ever expect, particularly since the Federalists at the convention needed their votes. Eventually, the agreement was found for the bicameral compromise suggested by John Dickinson of Delaware, which consisted of a Senate selected and presumably voting as states, and a House of Representatives elected in proportion to population; with all bills requiring the concurrence of both houses. From the perspective of two centuries later, we can see that allowing state legislatures to redraw congressional districts gives them the power to "Gerrymander" their election outcomes and hence restores to the populous states some of the internal Congressional power Washington and Madison were trying to take away from them. In the 21st Century, New Jersey is an example among a number of states where it can fairly be said that the decennial redistricting of congressional borders accurately predicts the congressional elections for the following ten years. The congressional seniority system then solidifies the power of local political machines over the core of Congressional politics. However, the irony emerges that Gerrymandering is impossible in the Senate, and hence legislature control over their U.S. Senators has been weak ever since the 17th Amendment established senatorial election by popular vote. That's eventually the opposite of the result originally conceded by the Constitutional Convention, but possibly in accord with the wishes of the Federalists who dominated it.

|

| Electoral College Method for Election of the President |

This evolving arrangement of the national legislative bodies seemed in 1787 an improvement over the system for state legislatures because the Federalists believed larger legislatures would contain less corruption because they had more competing for special interests to complain about it. There were skeptics then as now, who wished to weaken the tyranny of the majority so evident in the large states and in the British parliament. To satisfy them, power was redistributed to the executive and judicial branches, which were intentionally selected differently. Here arises the source of the Electoral College for the election of the President. It gives greater weight to small states (and provokes a ruckus among large states whenever the national popular vote is close). Further balance in the bargaining was sought by lifetime appointments to the Judiciary, following selection by the President with the concurrence of the Senate. Without any anticipation in this early bargaining, an unexpectedly large executive bureaucracy promptly flourished under the control of the chief executive, lacking the republicanism so fervently sought by the founders everywhere else. This may be in harmony with the Federalist goal of removing patronage from legislature control, but Appropriations Committee chairmen have since found unofficial ways to assert pressure on the bureaucracy. It's quite an unbalanced expedient. Only in the case of the Defense Department is the balancing will of the Constitutional Convention made clear: the President is commander in chief, only Congress can declare war. Although this difficult process was meant to discourage wars, it mainly discouraged the declaration of wars; other evasions emerged. From placing the command under an elected President, emerges a stronger implicit emphasis on civilian control of the military, loosely linked to the fairly meaningless legislative approval of initiating warfare. There have been more armed conflicts than "declarations" of war, but no one can say how many there might otherwise have been. And there have been no examples of a Congress rejecting a President's urging for war.

And that's about it for what we might call the first phase of the Constitution or the Articles. In 1787 there arose a prevalent feeling that national laws should pre-empt state laws. In view of the need to get state legislatures to ratify the document however, this was withdrawn. The Constitution was designed to take as much power away from the states as could be taken without provoking them into refusing to ratify it. Since ratification did barely squeak through after huge exertions by the Federalists, the Constitution closely approaches the tolerable limit, and cannot be criticized for going any further. Since no other voluntary federation has gone even this far in the subsequent two hundred years, the margin between what is workable and what is achievable must be very narrow. Notice, however, the considerable difference between Congress having the power to overrule any state law, and declaring that any state law which conflicts with Federal law is invalid.

The details of this government structure were spelled out in detail in Sections I through IV. However, just to be sure, Section VI sums it all up in trenchant prose:

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding. The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.

Except for some housekeeping details, the structural Constitution ends here and can still be admired as sparse and concise. That final phrase about religious tests for office sounds like a strange afterthought, but in fact, its position and lack of any possible ambiguity serve to remind the nation of grim experience that only religion has caused more problems than factionalism. Madison was particularly strong on this point, having in mind the undue influence the Anglican Church exerted as the established religion of Virginia. There are no qualifications; religion is not to have any part of government power or policy. By tradition, symbolism has not been prohibited. But government as an extension of religion is emphatically excluded, as is religion as an agency of government. Many failures of governments, past and present, can be traced to an irresolution to summon up this degree of emphasis about a principle too absolute to tolerate wordiness.

Globalization

|

| Peter Aloise |

The Right Angle Club recently heard from one of its own members about the complex issues involved in the topic of globalization. Peter Alois defined globalization as the development of an increasingly integrated world marketplace, although enthusiasts call it Free Trade, and opponents say it interferes with Fair Trade. Although there can be local exceptions, globalization generally leads to lower prices, so consumers are pleased, producers are worried. Since Free Trade can be defined as international commerce without government interference, globalization can also be defined as a general reduction of government influence in trade. But whether you love it or fear it, globalization is a reality; it is here.

Hindrances to trade can take many forms, including subsidies to local merchants, who then can underprice foreign competitors. Carrying things to an extreme, the French fairly recently prohibited the use of American words. While the reasoning used to justify this intrusion into private life was the preservation of the beauty of native French phonetics, this unfortunate government adventure calls attention to the possibility that one of the main functions of local languages is to make it difficult for foreigners to understand what is being said. The Anglo-Saxon response tends to note the large expense of teaching foreign languages in our schools, so why doesn't the rest of the world just stop the nonsense and start speaking English?

|

| Dubai Waterfront |

There does seem to be something about this issue related to fair play, a thoroughly Anglo-Saxon concept. When corruption of trade practices around the world is ranked, it is notable that both New Zealand and Canada, which are ranked at the top, are former British colonies. Somalia, certainly one of least British of countries, is ranked at the bottom. No doubt the French would be offended by this observation. It is also irksome to Fair Trade advocates (ie Globalization opponents) that national prosperity is also fairly parallel to Free Trade policies, absence of corruption, and so on. It was George Washington (probably ghost-written by James Madison) who most famously framed the American Doctrine: Honesty is the best policy.

Some of the members of the Right Angle Club, an outspoken lot, took up the other side of the proposition. Underpricing by foreigners leads to competitive advantage for them and loss of jobs for Americans. This dislocation is the unfortunate side of creative destruction, and a compassionate government should assist its wounded casualties. Whether it should go to the lengths of raising prices for other Americans by hobbling the foreigners, is a more open question. In the passion of argument, it was mentioned that this country was founded on such principles. Well, it would be hard to find anything written in the Constitution or spoken in its debates which supports that claim. But it must be admitted that the new nation wasted little time in creating new tariff protection for struggling new American manufactures, but took an awfully long time to get rid of what protective tariffs it already had. The confusions of the newly developing Industrial Revolution were perhaps not the best time to develop enduring principles of trade fairs, and thus we should not necessarily be held to them forever. But there is certainly room for the argument that a nation may need a certain set of policies when it is new and struggling, that are not necessarily appropriate when it becomes rich enough to claim to dominate world trade.

Tour of Duty in 'Nam

|

| Vietnam War |

Col. Dan McCall talked to the Right Angle Club about wartime experiences in Vietnam recently. He really didn't want to, though he was being asked to talk about retirement planning, or asset allocation, or something else he knew something about. But the Program Chairman this year is also a Colonel, and wasn't about to be talked out of it; he wanted Vietnam, sir, and nothing else. So, for the first time in forty years, he did. He hadn't talked about it with his family or, during a career rising from Lieutenant to Colonel, with his associates in the National Guard.

Perhaps a little slow and fumbling at first, we heard of going to a place where it's 120 degrees in the shade, every day. Where he fainted from a heat stroke on the first day off the plane in Saigon, and soon found that it happened to everyone. Within thirty days, every single person had dysentery. The plane that lands troops in Saigon doesn't turn off the engines, and takes off as soon as the last man deplanes. As well it might because it attracts sniper fire as it takes off. Once there, the only form of transportation for anyone going anywhere is by helicopter; plenty of peasants with chickens in their laps are taken along, too.

|

| Ho Chin Minh Trail |

His unit, the 82nd Airborne, was deployed to the west of Hue, the ancient capital. The country is near the border with North Vietnam, and the land is a fairly narrow strip between the ocean and the Laotian border. The Ho Chi Minh trail, where the enemy comes from, is just over the border inside Laos. Our troops never go there, but B-52 bombers go there plenty, leaving impressive craters in the ground. The unit was mortared every night, and rockets made an impressive noise as they went overhead toward Hue. The American forces almost never went out at night. Deployments in the jungle lasted 45 days, without baths or toilets; mostly, you walked into the enemy by accident on the trail. One of the prizes was a Chinese officer, carrying much better maps of the region than the American Army had. One night, sniper fire seemed to be coming from a small island in the river, and the response was to send thousands of shells back, filled with 3-inch steel darts. The next morning, every tree on the island was normal enough on the Laotian side, but nearly covered with steel darts on the Vietnam side. Although the command from headquarters was to report a body count, there were no bodies to count. At the end of one 45-day deployment, there had been no food or water for three days. When the "ships" came to take them out, there was a celebration with rice wine. You make rice wine by soaking stalks of rice in water, letting it ferment. The water is pretty murky, to begin with, and gets worse as it ferments; you have a good time, anyway, with the villagers bringing in a pig to roast.

|

| 82nd Airbourne Patch |

The CIA had its own private army, Rangers and Special Forces. There were local mercenaries, mostly from Thailand. The 82nd Airborne - The All American Division - had a tradition of parachute jumping in every military engagement since World War II, but in the jungle there was no place for, or point in, jumping. But at the end of their deployment, they jumped once, anyway. When you got home, the movies were kind of a joke, but Apocalypse Now came close to giving the right feeling. Although of course people asked what it was like, you didn't talk about it. No one did.

One member of the Right Angle Club who had spent a year there, muttered an answer. "And people didn't really want to hear about it, either."

Thieves of Baghdad

|

| Col. Matthew Bogdanos |

Col. Matthew Bogdanos, of the U.S. Marines, gave an interesting insight into what the Baghdad Museum really was, how it was captured, and how the treasures were recovered, at the University of Pennsylvania Museum the other night. Our own museum is said to be the second largest archeology museum in the world, after the British Museum. After discovering what was really in the Baghdad museum, that ranking may have to be revised; but the chief Philadelphia interest traces back to the discovery of the ancient city of Ur by Philadelphia archeologists during the last century, an event which essentially created the University Museum. This was where civilization began, and we discovered it.

The reserve Colonel happens to be a prosecutor for the New York District Attorney, was trained extensively in classical antiquities; and so was the perfect point man to lead the capture of the Museum during the Iraq war, very well suited to follow the looted treasures into the international antiques market -- and recover substantially all of it. Something like 62,000 pieces were recovered, and all of Nimrud's Treasure, the prize possession of the museum.

|

| The Baghdad Museum |

There has been criticism of our troops -- some of it right out of this evening's Philadelphia audience -- for allowing the place to be looted in the first place. But that sort of assumes the place was lying vacant and undefended while our troops were out shooting innocent civilians. That's a misapprehension quickly dispelled by videotaped scenes of real live shooting and rockets coming out of the place at the time, which the Colonel was happy to display. Questioners were invited to claim they would have been willing to go into that hornet's nest in order to save alabaster statues, but others in the audience inclined to giving the Marines some benefit of doubt.

|

| Hussein Millions |

That place was vandalized when the troops got into it; to say it was thoroughly vandalized is only true in a sense. There was indeed a lot of looting, but the bigger surprise was to find there were hidden storage rooms behind steel bank doors, filled with the really best antiques, as well as vast boxes of American hundred-dollar bills. By weighing the hundred dollar bills (22 pounds for every million dollars) it was estimated that Saddam Hussein had about $800 million in U.S. currency stored in that one place. Gold as a raw commodity has since gone up considerably in value, but many of the best antique gold pieces on display in the museum were only copies, the originals were kept in the secret vaults. The international market appraises quite a few of these pieces at over $10 million apiece. Apparently, the thieves knew exactly which pieces were valuable, and went straight to them without even pausing to notice other rooms full of objects of lesser value. The museum had been closed to the public for the previous twenty years; it seems rather obvious that Saddam was storing these objects in order to buy weapons for continuing guerilla activities underground, or in exile. The museum itself consisted of nearly twenty separate buildings in the center of Baghdad, and the custodians obviously must have known where things of serious value were kept, in order to get to them so precisely.

|

| Nimrud's Treasure, |

Offering an amnesty, no questions asked, brought in thousands of recoveries from the local public. Getting other pieces back from art galleries in London, Geneva and Berlin required methods that were not described in detail. Some of us who remember the German and Japanese mementos which were "liberated" during World War II have an immediate appreciation of the improved American troop discipline which must have been imposed in the Iraq War. That's something to think about, too. Our troops had been given extensive training to respect the cultural heritage of the enemy, and they evidently did so to a remarkable degree. One certainly has to doubt that Saddam was locking that material in vaults for twenty years in order to preserve the culture of any sort. If it had any other purpose than to serve as a way of transforming oil wealth into munitions, it's a little hard to imagine what it was.

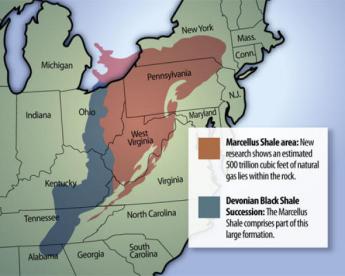

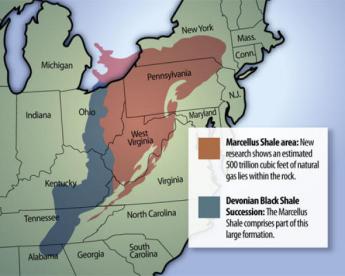

Marcellus Shale Gas: Good Thing or Bad?

|

| Marcellus Shale |

Soon after discovering widespread hard and soft coal, Pennsylvania found in Bradford County it also had oil. Local oil was particularly "sweet", with a low sulfur content. Long after much cheaper oil (cheaper to extract, that is) was found in Texas and Arabia, Pennsylvania oil was prized for the special purpose of lubricating engines, which commanded a higher price. This discovery of oil in the western part of the state also provided a vital competitive advantage for local railroads. Other east-west railroads like the New York Central and the Baltimore and Ohio lacked a dependable return cargo like this, so the Pennsylvania Railroad lowered prices and became the main line to the west for a century. Refineries were built in Philadelphia, and continue to dominate Atlantic coast gasoline production, even though the source of crude oil is mostly from Africa. When oil and coal declined in use, Pennsylvania's industrial mightiness declined, too. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh lost much of their competitive advantage, while the center of the state just about went to sleep. When even Texas oil later ran low, America's industry turned to computer-improved productivity to keep its prices competitive, helping California at the expense of Pennsylvania. The bleakness for Pennsylvania may not last, however. Suddenly, we discover we have another enormous source of cheap energy, shale gas.

It's rather deep, however, even deeper than our supply of fresh water. The next layer below surface minerals is porous rock filled with fresh water, the so-called aquifer. Gas bearing shale is layered just under the aquifer. We'll return to the aquifer later.

There is and will be abundant oil in the world, well into the future; but cheap oil has been selectively depleted. When military and economically weak nations like the Persian Gulf had cheap oil, only transportation costs were irksome. But now Russia is emerging as an oil-rich state, previously impoverished states like Iran are asserting themselves, the existence of an international oil cartel becomes more threatening because it reinforces oil price with military threats. Raw material discoveries -- gold rushes -- are always destabilizing because they are tempting to the dictator mindset. That's known in the political literature as the source of the "Dutch Disease", not because Netherlanders are aggressive, but because North Sea oil discoveries destabilized the politics of even that little peaceful nation. America has now made a universal decision to establish energy independence. It once was credible to make predictions that in a decade or two, we would run out of competitively priced energy. To be both rich and weak invites aggression and we knew it.

|

| Gas Drilling |

There's little question America is profligate with its energy, so the need for energy conservation is undisputed. Actually, we are already five times more efficient with energy use than China is; furthermore, we have improved energy efficiency by 20% while China has defiantly worsened. We'll do better, but unfortunately, our immense investments in inefficient home heating and transportation are too costly to discard abruptly in both cases. There is also little question that American research and development of alternative energy sources has been neglected, while China is subsidizing R & D appreciably. In our frenzy, converting food into gasoline by subsidy is a bad joke, electric cars are subsidized and widely described as "Welfare buggies", wind power is twice as costly as carbon-sourced energy and needs better battery development to be able to store it, atomic energy has been encouraged by the French government, but totally held back by ours, in response to public anxieties. The long and the short of it is this: we face a fifteen-year period of doubtful energy sources, a vulnerability our international competitors and enemies might easily use against us.

And then along came shale gas, like a gleaming savior on a white horse. For seventy-five years, the world has known unlimited amounts of petrol carbons are locked into vast stores of shale. Unfortunately, it is buried deep, and located where it is expensive to transport to market. The techniques for extracting such carbons were unacceptably expensive in a world that shrugged off abundant oil. Politics and geology turned against us; we now need fifteen years of catch-up to make alternative energy sources more affordable. Cheap oil ran out before non-carbon sources became practical. But miraculously shale gas is now upon us, right here in Pennsylvania. It takes a long time to map out the existence of shale from Canada to Texas, when it is 8000 feet deep; it was first recognized in 1839 from a cliff outcrop around the little town of Marcellus, New York and vigorously explored in the disappointed hope it would lead to discoveries of bituminous coal, iron ore or other minerals. Land speculators have been roaming Pennsylvania for two centuries. Now, they are offering $5000 an acre plus royalties, just for the right to drill. In 2010, probably 5000 leases will be issued. Needless to say, the discovery is popular with local farmers, and "gas fever" has enormous political momentum. With techniques discovered around Fort Worth, Texas, about 10% of the existing gas can be extracted easily, serving America's energy needs for much of the 15 years required to make renewable, non-fossil, energy cheap and practical. This long history paradoxically accounts for the apparent suddenness of the current popularity; it's not a new mineral discovery, it is the development of practical extraction methodology at a critical political and marketing moment.

|

| Tree Hugger |

And equally needless to say, the environmental movement is being called to its barricades. Whatever is their objection to drilling for gas, 8000 feet below the surface of a wilderness? In the first place, just cutting roads through the forests is destructive to migrating and local bird populations. In a well-known process of "fragmentation", the cutting of roads allows an invasion of raccoons and similar bird predators. Forest fragmentation simply cannot be avoided if drilling rigs are to enter and leave the forests; some vulnerable bird species are bound to go extinct. This particular region is particularly prone to emissions of radon, which is a radioactive gas traveling along the stone layer and occasionally entering the basement of houses; will drilling through to the shale layer make radon seepage better or worse? Furthermore, since this sedimentary shale layer lies underneath the aquifer, drilling must go through the freshwater-bearing caverns before it gets to the shale; expensive sealing methods may be needed to keep the contaminants below from seeping up through and around the drill holes. The practice of fracturing the shale by high-pressure mixtures raises issues with water, sand, and chemicals. Water consumption is millions of gallons per year per well, seemingly enough to drain the rivers and creeks. Some operators will be tempted to use the aquifer as a surreptitious source of water, leading to consequences hard to anticipate. The sand is meant to support the walls of the rock fractures but may clog up other channels unintentionally. And the composition of the chemical drilling components is a trade secret which the extraction companies naturally wish to keep private; it's pretty hard to get public approval of a secret. So to sum it all up, there is a legitimate need to hurry the drilling, and there are legitimate environmental safety issues to be addressed, slowing it all down. New York State has passed laws prohibiting further drilling. Is that an opportunity for Pennsylvania, or a warning we should heed?

|

| Where's My Aquifer? |

This is a time for serious negotiation, and the spending of serious amounts of money on study and monitoring, not for shouting. Politicians sense you can't make omelets without breaking eggs. For them, it's a question whether to choose to be blamed for the inevitable problems of exploring new science, or whether to be blamed for lack of patriotism in a national emergency. The amount of heedless rhetoric is predictably extreme, and the money available to spin it is daunting. If there is anything resembling a middle road in this uproar, let's explore it. In the first place, some sensible discussion between scientists of both sides can be held immediately. Geologists are probably unaware of issues like forest fragmentation, while naturalists are probably unfamiliar with radon hazards and available drilling precautions. Some concerns are exaggerated, some are unsuspected; let's get the experts together quickly and establish most of the knowns and unknowns before popular media runs away with the issue. Let's get the responsible leaders of the gas extraction industry into continuous dialogue with the responsible leaders of environmental protection organizations, so wars they get dragged into are real and not hysterical. Let Congress consider the issue and appropriate funds immediately to study the issues everybody agrees need to be addressed. It seems very likely the huge corporations involved in this issue will rather easily agree among themselves on responsible positions unless they get rattled by overly vocal denunciations. Since this is a gold rush, however, it is also likely that underfunded small operators will start to employ short-cuts and rush heedlessly into dangerous territory; large operators will wish to have laws passed to restrain everybody, small operators will plead fairness. The more transparency this field has, the better. And the most immediately obvious area of resistance to transparency is the natural wish to protect trade secrets in the composition of drilling fluids. In time, the other continents of the world will develop satisfactory drilling fluids; the secret won't last long. The situation cries out for the large operators to negotiate among themselves so those who have an incentive to protect secrecy can tell us how to do it responsibly, while those with a political incentive to expose secrets can be offered time limits related to the how fast the rest of the world catches up. Politicians particularly need to be offered some mechanism for assuring the public about those secret injection ingredients.

Anyway, let's negotiate a way to take chances we have to take, but avoid the costly blunders of studying the issue to death. Hurry up, folks, it's a matter of time before problems have to be faced.

Aftermath: Who Won, the States or the Federal?

|

| Thirteen Sovereign States |

In the case of the American Constitution, the initial problem was to induce thirteen sovereign states to surrender their hard-won independence to a voluntary union, without excessive discord. Once the summary document was ratified by the states, designing a host of transition steps became the foremost next problem. The dominant need at that moment was to prevent a victory massacre. The new Union must not humble once-sovereign states into becoming mere minorities, as Montesquieu had predicted was the fate of Republics which grew too large. Nor must the states regret and then revoke their union as Madison feared after he had been forced to agree to so many compromises. As history unfolded, America soon endured several decades of romantic near-anarchy, followed by a Civil War, two World Wars, many economic and monetary upheavals, and eventually the unknown perils of globalization. When we finally looked around, we found our Constitution had survived two centuries, while everyone else's Republic lasted less than a decade. Some of its many flaws were anticipated by wise debate, others were only corrected when they started to cause trouble. Still, many tolerable flaws were never corrected.

Great innovations command attention to their theory, but final judgments rest on the outcome.

|

| . |

Benjamin Franklin advised we leave some of the details to later generations, but one might think there are permissible limits to vagueness. The Constitution says very little about the Presidency and the Judicial Branch, nothing at all about the Federal Reserve, or the bureaucracy which has since grown to astounding size in all three branches. Political parties, gerrymandering, and immigration. Of course, the Constitution also says nothing about health care or computers or the environment; perhaps it shouldn't. Or perhaps an unmentioned difficult topic is better than a misguided one. Gouverneur Morris, who actually edited the language of the Constitution, denounced it utterly during the War of 1812 and probably was already feeling uncomfortable when he refused to participate in The Federalist Papers . Madison's two best friends, John Randolph, and George Mason, attended the Convention but refused to sign its conclusions, as Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson almost certainly would also have done. On the other hand, Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris came to the Convention preferring a King to a President, but in time became enthusiasts for a republic. Just where John Dickinson stood, is very hard to say. Those who wrote the Constitution often showed less veneration for its theory, than subsequent generations have expressed for its results. Understanding very little of why the Constitution works, modern Americans are content that it does so, and are fiercely reluctant about changes. The European Union is now similarly inflexible about the Peace of Westphalia (1648), suggesting that innovative Constitutions may merely amount to courageous anticipations of radically changed circumstances.

|

| President Franklin Roosevelt |

One cornerstone of the Constitution illustrates the main point. After agreeing on the separation of powers, the Convention further agreed that each separated branch must be able to defend itself. In the case of the states, their power must be carefully reduced, then someone must recognize when to stop. If the states did it themselves, it would be ideal. Therefore, after removing a few powers for exclusive use by the national government, the distinctive features of neighboring states were left to competition between them. More distant states, acting in Congress but motivated to avoid decisions which might end up cramping their own style, could set the limits. The delicate balance of separated powers was severely upset in 1937 by President Franklin Roosevelt, whose Court-packing proposal was a power play to transfer control of commerce from the states to the Executive Branch. In spite of his winning a landslide electoral victory a few months earlier, Roosevelt was humiliated and severely rebuked by the overwhelming refusal of Congress to support him in this judicial matter. The proposal to permit him to add more U.S. Supreme Court justices, one by one until he achieved a majority, was never heard again.

|

| Taxes Disproportionately |

Although some of the same issues were raised by the Obama Presidency seventy years later, other more serious issues about the regulation of interstate commerce have been slowly growing for over a century. Enforcement of rough uniformity between the states rests on the ability of citizens to move their state of residence. If a state raises its taxes disproportionately or changes its regulation to the dissatisfaction of its residents, the affected residents head toward a more benign state. However, this threat was established in a day when it required a citizen to feel so aggrieved, he might angrily sell his farm and move his family in wagons to a distant region. People who felt as strongly as that was usually motivated by feelings of religious persecution since otherwise waiting a year or two for a new election might provide a more practical remedy. However, spanning the nation by railroads in the 19th Century was followed by trucks and autos in the 20th, and then the jet airplane. While moving residence to a different state is still not a trivial decision, it is now far more easily accomplished than in the day of James Madison. A large proportion of the American population can change states in less than an hour if they must, in spite of a myriad of entanglements like driver's licenses, school enrollments, and employment contracts. The upshot of this reduction in the transportation penalty is to diminish the power of states to tax and regulate as they please. States rights are weaker since the states have less popular mandate to resist federal control. It only remains for some state grievance to become great enough to test the present power balance; we will then be able to see how far we have come.

|

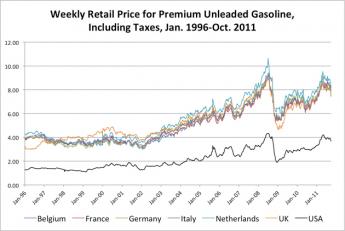

| High Gasoline Taxes of Europe |

Since it was primarily the automobile which challenged states rights and states powers, it is natural to suppose some state politicians have already pondered what to do about the auto. The extraordinarily high gasoline taxes of Europe have been explained away for a century as an effort to reduce state expenditures for highways. But they might easily be motivated by a wish to retard invading armies or to restrain import imbalances without rude diplomatic conversations. But they also might, might possibly, respond to legislative hostility to the automobile, with its unwelcome threat to hanging on to local populations, banking reserves, and political power.

It helps to remember the British colonies of North America were once a maritime coastal settlement. The thirteen original states had only recently been coastal provinces, well aware of obstructions to trade which nations impose on each other. Consequently, they could readily design effective restraints to mercantilism within the new Union. Two centuries later, repeated interstate quarrels provided fresh viewpoints on old international problems. As globalization currently becomes the central revolution in trade affairs of a changing world, America is no beginner in managing the intrigues of international commerce. Or to conciliating nation states, formerly well served by nation-state principles of the Treaty of Westphalia, but this makes them all the more reluctant to give some of them up.

Mexican Immigration and NAFTA

|

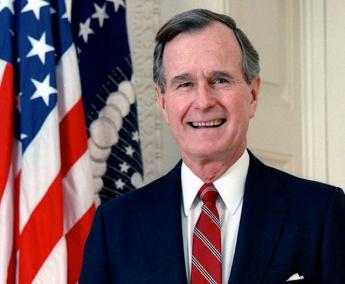

| George H.W. Bush |