Related Topics

Philadelphia Economics

economics

Whigs, Slaves, and Tariffs

At the time of the Revolution, Philadelphia had 25-30,000 residents. Although then it was the largest city in North America, today it would compare with a small suburb. By the time of the 1800 census, Philadelphia had 67,000 residents. The Capitol was moving to Washington; Philadelphia's fifteen minutes of fame were over. Still, the city had only achieved the size of what we would now call a one-industry town. The fifty state capitals today are about that size; look there if you want to observe the mentality and social structure of one-industry towns.

|

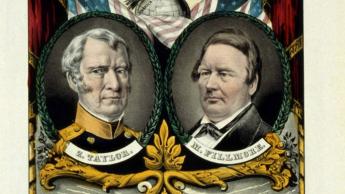

| Zachary Taylor, His vice president, Millard Fillmore |

But by the 1850 census, Philadelphia's population was 408,000, 30% foreign-born. That's an entirely different environment. By the time of the Civil War, Philadelphia was a real city, with real growing pains. The rest of the country had similar problems, with different details. The voting franchise was extended beyond land-owning taxpayers in 1838, mostly affecting backwoodsmen who had immigrated a century earlier. In Philadelphia and other seaboard cities, however, the franchise was extended to factory workers from foreign cultures, and the result was natives. Street riots calmed down into politics but transformed into politics. "Know Nothings." a Nativity political party was named for its pledge to say "I know nothing" when the police arrived. (Philadelphia's 1854 city-county consolidation can be traced in part to a need to get local police forces to follow orders.) The extension of the franchise could be traced back to the 1828 election of Andrew Jackson, and it could be traced forward to the creation of modern political parties. The founding fathers supposed that leaders would be elected on the basis of deference, with a town like Philadelphia run by the Biddle's, Ingersoll's and Wharton's. And in fact, that was mostly how it was until 1828. After that, it was just a matter of time before the only thing that counted was the only thing that was being counted - votes. Since that time, business and social elites have from time to time rebelled with what they called "reform movements." But as Adlai Stevenson wryly remarked, it takes a majority to win. Election of elites is always and everywhere a rarity.

The critical moment for Philadelphia and the Republican Party came in a smoke-filled room in the 1850s when the anti-slavery movement was united with the Nativity Know-Nothing Party. Both of these parties held their national presidential convention in Philadelphia in 1856.In the background was dissolution of the Whig Party, and on the table was the protectionist tariff. The Whigs were an idealistic group, and Lincoln had been a fervent Whig. Their theme was building canals, roads, railroads and other features designed to promote prosperity by enhancing the economic infrastructure. The weakness of the Whigs lay in the way their approach usually raised taxes. The Know Nothings were far from idealistic; their weakness lay in the general fear they were promoting class warfare.

Someone proposed that the common ground between the two splinter parties lay in advocating the protective tariff. Of course, that's another bad idea, but as a vote-getter it was wonderful. It united the workers with the business owners, potentially enriching both of them. More importantly, it reassured the idealistic Whigs and abolitionists that class warfare could be avoided. Freeing the slaves, conversely, would appeal to businesses and workers who compete with slaves.

A hundred years earlier, Adam Smith had demonstrated that artificially raising prices impoverishes consumers, and the Wealth of Nations is thus always injured by tariffs. But anyway, on to the Wigwam, and on to Fort Sumpter.

Originally published: Thursday, July 15, 1993; most-recently modified: Friday, June 07, 2019