Related Topics

Causes of the American Revolution

Britain and its colonies had outgrown Eighteenth Century techniques of governance. Unfortunately, both England and America lacked the sophistication to make drastic changes smoothly.

Right Angle Club 2017

Dick Palmer and Bill Dorsey died this year. We will miss them.

The Stamp Tax: Highly Innovative, Much Underestimated

One of the great books about Benjamin Franklin has just emerged, and it has an interesting current Philadelphia connection. Benjamin Franklin in London fills in the eighteen years Franklin spent in Europe, with many details and insights not possible to have with three thousand miles of ocean separating his activities from his home base. In fact, it raises the question of what was really his home in his own mind. Boston claims him because he was born there, but it takes a London writer to tell us he moved to Philadelphia because of disputes over vaccination for the smallpox epidemic, between his publisher brother and Cotton Mather. XX Goodwin, writer in residence at the Craven Street Ben Franklin Museum, will forever change our views about his subject. We hope he produces much more.

A word about the museum. The Craven Street house is the only Franklin residence still standing, restored with funds from Countess XX, Anthony Biddle's XXX, who unfortunately died this year. Her daughter, Charlotte Petropolis has an apartment in Philadelphia and regularly attends meetings of the Shakspere Society at the Philadelphia Club, which is itself the oldest club in America, and second oldest in the world, according to Matt Dupee, one of the local authorities on such matters, himself a member of a great many clubs around the world. To return to the original point, Goodwin is the beneficiary of this important interest by prominent Philadelphia families in our Founding Father.

|

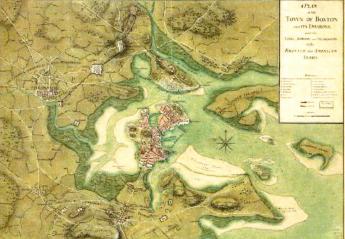

| Revolutionary Boston Reconsidered |

One gathers from the book that Franklin had considered himself a lifelong British subject, and from the Albany Conference of 17XX to his abject public humiliation in the "Cockpit" of Whitehall in 1775, nursed the hope that Great Britain and America would join in an empire as equals. He foresaw the growth of America, and expected the capital of the joint empire to move to America. After he returned to America, of course, the gauntlet had been thrown down, and he made it his task to enlist France on our side, bankrupting France and thus eventually provoking not one, but two national Revolutions. The French still think of him as their darling, but the lessons of the French Revolution taught Franklin some things he needed to know at the American Constitutional Convention of 1789. Letting others like Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris do the talking, his influence at dinners and private meetings put a stop to egalitarian babble and established a firmly Federalist nation. His activity in London would have won him a Nobel prize instead of fairy tales about kites and keys, he was friends with Mozart and Beethoven, plus about five kings. You don't humiliate a man like that without living to regret it, and King George III certainly regretted it in his saner moments.

Which, after three paragraphs, brings us back to the Stamp Tax of 17XX. To begin with, it isn't enough to want to do something, you must figure out a way to get it done. The early 18th Century colonists had learned that smuggling and counterfeiting would frustrate any tax plan for colonies so far away with diversified economies. The oceans were filled with pirates, sometimes described as privateers, and the American coastline was thousands of miles long. Furthermore, maintaining a large British navy from the Spanish Armada to the War of the Austrian Succession required thousands of British sailors, and the Navy had been stripped down to spare expense. So naturally the idea came up to have the colonies pay for their own defense at least, but how were you going to do it, in a way you could afford to continue?

A little digging in history would probably reveal the main author of the Stamp Tax Act, but such things are often the product of staff rather than the parliamentary member who introduced them. But it ingeniously solved the empire taxation problem. You just printed up the stamps and sold them, then required the objects of taxation to have a stamp pasted somewhere on them. You still would have to worry about smuggling and counterfeiting, but the whole thing was an inexpensive way of collecting the money and enforcing the tax. It even provided some nice patronage jobs for loyal stamp sellers.

Apparently, it was much too clever by half, since the colonists could immediately see what might be ahead of them. An uproar ensued, leading ultimately to repeal of the tax, except for a token tax on tea in order to preserve the principle. But the principle was exactly what bothered the colonists, and a tea tax wouldn't do, either. The rest is history, except I don't happen to know whose idea it really was. But I do know that Franklin was in London at the time, and Franklin's inclinations were strongly in favor of a combined British Empire. Franklin almost lost his job in this uproar, and some of his fellow colonists may have suspected his personal position on it.

Originally published: Wednesday, March 30, 2016; most-recently modified: Friday, May 31, 2019