Related Topics

Introduction: Surviving Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

New topic 2016-03-08 22:42:53 description

"Christmas Saving Fund" for Medical Care

After listening to a description of a Health Savings Account (HSA), the nice Quaker lady exclaimed, "Why, it's just a Christmas Saving Fund for health care!" And so it is. First, you buy a health insurance policy which pays the cost of major illnesses above a fairly high cash deductible. And second, you create a special savings account -- independently and tax-free. That one is to build up the cash deductible, and/or outpatient health expenses below (too small to trigger) the insurance.Once your savings account has at least reached the deductible level, you are totally covered for major health expenses -- from the first dollar to last, just like Blue Cross used to be, long ago. True, you still must pay small outpatient costs, but passing them through the account reduces their cost by the income tax deduction. We hope you just keep on adding to the account as you are able, tax-free up to $3350 per year ($3400 next year), but the decision is yours alone.

Something significantly extra emerges at the age you become eligible for Medicare. We therefore even suggest a name-change of HSAs, to Health and Retirement Savings Accounts,(HRSA), because any surplus from remaining healthy turns into an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) when you convert to Medicare. For some people, this retirement addition is more important than the health care part. It will all depend on whether your health has been robust, average, or sickly. For most people, it has been robust.

As far as healthcare coverage is concerned, many speeds of differing amounts will reach the same finish line, so the Health Savings Account invites the subscriber to choose the speed he can afford to risk, periodically, to reach the deductible (or even more). In fact, there are incentives at every turn to save more, because some people won't save unless prodded a little. In fact, the average American spends $2000 annually on loan interest, because he can't resist the temptation to buy things.

But you can always delete this particular account's balance for an illness, then restore or exceed it tax-free, if part of the balance does happen to be needed for healthcare. Meanwhile, the account earns tax-free income. It isn't hard to understand, particularly if you read the description twice, but its hidden power may be less obvious. The old Blue Cross system had a "use it or lose it" quality to it, but the Health (and Retirement) Savings Account gives you back anything left over, as an incentive to save for retirement. The first part of this book tries to make clear how important the difference is. (See the table at the bottom of this first section.)

Because both deposits and medical withdrawals are untaxed, the system offers the advantages of both a regular IRA and a Roth IRA, combined. The only disadvantage to overfunding the account is to pay a penalty for non-health expenditures from it before age 65. After the HSA subscriber reaches Medicare eligibility, it all turns into an Individual Retirement Account, which you can spend on anything you please. Since you can't predict what your health will be, the harmless incentive is to keep it overfunded to get more tax abatement, but nevertheless, that's not required.

* * *

That's unique and simple, and all quite true, but it describes only a fraction of the full potential of HSAs, which require the rest of this book to explain. Read the first four short paragraphs again if they seem unclear. Much of their potential wasn't dreamed up by the originators (John McClaughry and me) at all but just tumbled out as patient experimentation and experience accumulated. It's tested, all right. Between fifteen and twenty million Americans already have these accounts. As things turn out, they are not merely attractive to poor people, although that's how they began. The original goal was to help people of average income afford what most people who work for big corporations had been given by their employers for decades, but innovative thinking has gone far beyond that modest beginning.

The Traditional, or Employer-based System. In spite of all the talk about healthcare reform, about half the population still retains the employer-based design, and they passively imagine the employer design only requires tweaking to be perfect. However, it remains relentlessly connected to the kind of job someone has. It begins when you get a job, and ends when you quit that job; that's a difficulty, right there. In employer groups, you don't buy it, your employer buys it and gives it to you as part of your salary, but you need not suppose your pay-packet is as big as it would be without it. The result is, the core of the employer system has become largely funded by tax deductions -- the employee's, (20-30%), and particularly his employer's at a higher rate (40%). The relentlessly rising costs it provokes are not the employee's problem nor his employer's problem; they are the government's borrowing problem and a big one. But the source of its cost inflation is the false appearance it is free. It isn't free. It may well be the main reason America's corporate income tax remains so high, driving our corporations abroad. Otherwise, it suppresses profits, take-home pay, dividends and tax revenue.

Employer-based health insurance is so full of cross-subsidies (both inside and outside the hospital), it would be hard to say who supports what. But clearly, young employees subsidize older ones and may lose out entirely if they change jobs, as they frequently do. Unfortunately, the Affordable Care system uses the same configuration but superimposes income groupings. Unless the Affordable Care Act changes, thirty million people will be specifically excluded from it. While it mandated uniform subsidies, its subsidy designations conflict with existing ones and cause problems which have not been solved in two extensions of the employer insurance mandate. Some subscriber groups match the government subsidy limits fairly well and prospered. But the components in other insurer groups do not happen to match the subsidies well and are threatened with considerable disruption. Stay tuned to hear how this works out.

Overall, the whole system is unbalanced, with the working third of the population struggling to support the non-working two thirds, too young or too old to be working. Thirty years have indeed been added to life expectancy in the past century, so it's hard for anyone to complain about the effectiveness of the American health system, except notice: not getting sick means a longer retirement, requiring more retirement income. Everyone wants to live longer, but few can afford a long vacation after the working years. Employer-based insurance encourages more spending; the illusion of being free encourages wasteful spending because neither the patient nor his employer have much "skin in the game". Its biggest problems grow out of its most attractive features. Everybody hates to admit it, but longer retirement costs are merely deferred, unfunded, healthcare costs, in a new form.

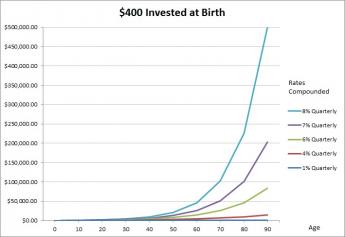

Further Advantages of Health Savings Accounts. Before going further, let's go back and notice what else tumbles out of the simple structure of the HRSA, or Health and Retirement Savings Account, which now becomes our central topic. First of all, it's usually lots cheaper. Sometimes it's hard to prove where the savings originate, probably about 15% from the account itself, and another 15% from the catastrophic (indemnity) health insurance. Eventually, any savings get greatly multiplied by compound interest.

Cost-Savings. The higher the deductible, the smaller the premium, is just mathematics, but it's a big reason this package appeals to financially struggling people. But notice what's obviously also true: the lower the deductible, the higher the premium. Seemingly, it should all come out the same, but in fact, it's cheaper. The HSA (Health Savings Account) started out as a new way to lower premiums temporarily, for people who didn't happen to be sick at that moment. However, if someone becomes sick, the average total of premium plus deductible, in the aggregate, surprisingly often turns out to be lower than regular insurance. That's when we started noticing its hidden features, trying to explain such hidden power. First of all, this approach probably does induce more young people who aren't sick, to buy insurance.

Having larger numbers of young subscribers lowers the average premium for everybody else because healthy youngsters essentially buy protection, not health services. Subscribers acquire some control of the premium price, but it's incomplete and they sense it, depending on insurance design. For the most part, young people overpay for protection. Nowadays, the Affordable Care Act sets mandatory deductibles for all health insurance plans, while ostensibly forcing everybody (except for 30 million embarrassing exceptions) to buy health insurance, too. That's supposedly a way of forcing premiums down, except it upsets people to be forced. And anyway, premiums for what satisfied the Affordable Care Act quickly went up higher(and alarmingly went up faster) than before. The cops and robbers approach didn't save money, probably because all government projects are "one size fits all", responding to the equal protection clause of the Constitution. That's nice, but it can't defy the law of gravity.

In better economic times, appreciable interest income is earned when young healthy people stay healthy for fifty years before they do get sick. Effectively, with an HSA you can pick any residual deductible you want, by taking more risk, or less, for a few early years. As the Christmas Fund builds up to the deductible and beyond, eventually you take no financial health risk at all and begin to take retirement risk. Let's say that again: by partially funding the insurance company's posted deductible, what's left unfunded is setting the true deductible. Most HSRA subscribers eventually fund it all and have no true remaining deductible when they get sick. But a funded deductible has changed the nature of the cost resistance. It now becomes one of protecting your investment, because you are surely going to need it, some time.

The amount of subscriber risk can remain only fuzzily described, whereas insurance companies must pay to the penny, and usually can't accept vague financial risks. This one stretches over too many years to be safe for them to predict, even in bulk numbers. Mismatches are numerous, between income and sickness experience. When you have enough money in the Health (and Retirement) Savings Account to pay a deductible, you essentially have first-dollar coverage. That doesn't exploit the full potential of HSAs, but it's at least one of the things it does. The fact that excess spending is less provoked is proof that a particular issue can be addressed. In addition, almost all modern insurance also has an upper limit to total cash out-of-pocket medical costs, but those limits are higher than the deductible. They were added to cover the remote possibility someone might have more than one illness in a limited time period. This soon gets to be a complicated insurance theory, but it includes a warning: you must know the risk if you are to assume it.

The designers of the Affordable Care Act evidently underestimated the amount of backlogged health maintenance they were assuming, and probably underestimated it by vaguely ascribing it to "pre-existing conditions." All you really need is to read the newspapers to see the Affordable Care Act is very close to getting insurers into financial trouble. (My local Blue Cross organization lost $56 million last year, and the whole industry probably lost a $billion.), thereby eventually passing big trouble on to the public. One of the major sources is an unsophisticated gap between the deductible and the lower limit of out-of-pocket costs. If you take a risk, you must know how much it is, or else who will assume it for you. To base that gap on the insurance company's need for risk limitation is a pretty crude approximation, which in fact presumes the government will assume it. Insurance executives surely knew this; whether the politicians did, is less certain. Obscuring the risk possibly doubles it, as two parties seek to protect themselves.

By contrast, the HSA subscriber does run a small but definable risk during the time the account is building up to the deductible level. He can guess at that risk, which is extremely small for young people, and hopes he won't get very sick for several years. Inevitably, older people have a greater risk because they have worse health. So right now everybody's safety rests on hustling to build up the account as fast as possible. Because it's a pretty good investment, it's a good idea to overfund the account whenever the subscriber has spare funds, just in case. Lots of poor people are too unsophisticated to have bank accounts. That's fine -- just overfund your HSA. Unfortunately, the Administration just applied a penalty for doing that in an unspecified way, a pretty vague if not unenforceable threat. I do suppose someone could get hit by a truck on the way home from buying insurance, but in that situation, the limit for uninsured costs would be the size of the deductible; if deposits had been made to the account, it would be less.

Once the gap is filled, you can change the premium or fill the account up a second time, but many people are often too unfamiliar with the twists and turn to achieve absolutely minimum costs. Rest assured, HSA is a pretty good investment although not a windfall, so unsophisticated people don't have much if anything to lose by overfunding it. Some have suggested the gap can be narrowed by buying life insurance, but cost statistics are not available to evaluate that possible approach. Someday, some enterprising insurance company will offer an automatic re-adjusting feature, but it would add cost. It requires a company to get involved without charging high fees, hoping only for big volume for a reward. Hoping for big volume implies heavy marketing investment; annuities are probably too expensive to serve the purpose.

The Retirement part is more important than the Medical part.

|

|

Eventually, the subscriber will discover more money in his account than he absolutely needs for healthcare (and the sooner he does, the better). Some people will buy a newer car, or a bigger house, send someone to college or pre-pay some future lean year of his own when he is between jobs. If those events describe his entire future, he needs to read no further. For some people, a sudden illness may, however, terminate their planning. For the rest, however, the big problem will be to avoid outliving their retirement income, usually because they remain so healthy, not because they spent their reserves on illness. We all secretly hope the future will be good to us.

In fact, paying for retirement in the future threatens to become such a large problem, it could dwarf illness as a threat for almost anybody. It begins to raise the question of what the main threat facing any particular person, really is. Thirty years of extra longevity are wonderful, but everyone needs a way to pay for them, particularly if they should turn into forty years. Taking the long, long view is what the rest of this book is all about: We seriously propose a solid foundation of Health and Retirement Savings Accounts as a bulwark for just about everyone's far future. Meanwhile, unless someone changes the rules, it's hard to see how very many people could lose money by getting started. The rest of this book shows ways to do still better than that, without getting hurt.

Originally published: Monday, February 29, 2016; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 09, 2019