Related Topics

Investing, Philadelphia Style

Land ownership once was the only practical form of savings, until banking matured in the mid-19th century. Philadelphia took an early lead in what is now called investment and still defines a certain style of it.

Right Angle Club: 2014

New topic 2013-11-19 20:22:11 description

Philadelphia's Fourth Century: Revival or Relapse?

Novelists, sociologists, playwrights, financiers, historians, poets -- and others -- have described and explained the rise and fall of Philadelphia. Each of them is a little bit right, and a little wrong. Philadelphia is hidden, but it isn't hiding.

Decline and Fall of Philadelphia

In 1900, Philadelphia was described as the largest commercial (ie non-capital) city in the world. By 1929 it was flat on its back, and never recovered its former position. Why did this happen?

Decline and Fall of Philadelphia

|

| 1929 Crash |

We talk high finance here, so perhaps a simple story from Wall Street is needed to introduce the topic to a non-Wall Street audience. Following the 1929 crash, and consequent to the Glass Steagall Act, Morgan Stanley was the only American investment bank in existence. It was the first of a new kind, but barely in existence, doing something like $300,000 worth of business in 1933. As finance adjusted to the new ground rules, Morgan Stanley grew in size, commonly referred to as the "White Shoe" investment bank. That term was an allusion to the Ivy League background of its partners, who came from colleges which affected white buckskin shoes among their more elite students. It also referred to the fact that almost all Morgan Stanley partners were pretty rich and fairly young, entirely able to live by a code of behavior which might be summarized as, "We don't find it necessary to cheat."

Buried within that motto was the idea that Morgan Stanley was as good as its word, and tried very hard to avoid doing business with anybody who did cheat. In a business where a great deal of business was transacted too quickly for written contracts or vetting by law firms, that meant a lot.

<Morgan Stanley soon climbed to the top of a very tough heap and stayed there for fifty years. Many of its partners were millionaires in their twenties, but so what, they were mostly pretty rich before they joined the firm. The company ran as a partnership, with the capital they leveraged coming from the personal fortunes of the partners. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising many partners retired in their forties, taking their enhanced capital with them. The Glass-Steagall Act (now being imitated by the Volcker Rule within the Dodd-Frank Law) made it illegal for a depository bank to be under the same roof with an investment bank. Much of the capital in the pre-1929 days had been supplied by the deposits in the depository bank, but Glass Steagall cut that off when it created depository insurance, on the theory that deposit insurance was a Federal gift, and its "moral hazard" should not flow through to the speculation of investment banking.

That comment was tinged with populism, with the dubious implication that those who are two generations off the farm are less likely to cheat than those who are five generations off the farm. So the depository bank of Morgan Guaranty has split away from the investment bank of Morgan Stanley, which was the three-step process by which Morgan Stanley eventually grew so big it could no longer be sustained by leveraging the personal wealth of its partners.

|

| Buy And Sell |

Eventually, the pressure to raise money by selling stock to the public could no longer be resisted. The rich partners became even richer by selling their company's stock on the stock exchange, the company did grow enormously, and a lot of new stockholders got rich, too. Unfortunately, when you sell a stock you also sell voting rights, so the sale transferred voting control of the company to the new stock purchasers. It did not take many years before the white shoe atmosphere was a thing of the past, along with the discipline that the atmosphere imposed on the rest of corporate America. When the 2008 crash came along, there was enough questionable behavior on Wall Street to justify a populist President of the United States to tolerate, or even encourage, a witch hunt of Wall Street bankers for ruining the country.

Even so brilliant an economist as Paul Volcker has encouraged the idea that separating the two forms of banks was an unmitigated blessing which must be restored, while in fact it is only justified by the gift of Federal Deposit Insurance to the depository arm, not the Investment Banking Arm. It seems only a matter of time before there will be agitation to extend the insurance to the investment arm so we will be chasing our own tail, of extending insurance to encourage risk-taking, instead of using demand deposits to do so. And thus inviting another crash.

I'm sorry, Paul, but there is a reversed way to describe it. The small investors demanded the entitlement of risk-free investing, protected by deposit insurance. And they declared this insurance was a special entitlement to which wealthy players were ineligible. When small punters go broke, it is a tragedy. When big players go broke, it serves them right for being so greedy.

|

| Gasoline |

Converting partnership or family businesses into stockholder organizations was a universal outcome of both World Wars, all over the world. The phenomenon can be looked at as one way of extracting frozen wealth to pay war debts. It is accompanied by an increase in national indebtedness, so it makes civilizations less stable. Scraps of partnership control do continue to persist in remote developing countries, and in tiny principalities like Luxembourg, but it seems only a matter of time before the public buys them out. The only major developed country to retain family control of businesses in Germany. Apparently, it was intentional, based on the inheritance laws. Tightly held countries are more commonly tightly held together by force, as in Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Monaco, usually because of a monopoly grip on oil or other natural resources. But even those governments could probably be toppled, except for fear of ensuing chaos, just as did happen to many former dictatorships, and was a source of fear in Philadelphia. A case can be made for populism if it is kept small and under control. Hardly any case at all can be made for chaos.

|

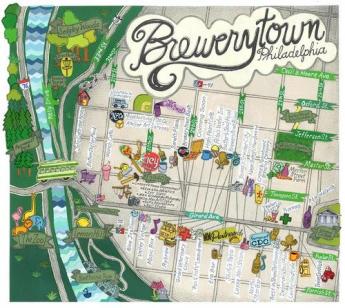

| Brewerytown Map |

For those of us who love Philadelphia and wonder what happened to it, let me point out three defining local peculiarities. Prohibition was more of a factor than we like to think because Philadelphia's Tenderloin was the former Brewerytown, filled with Beer Gardens, refrigeration plants (Lager beer is brewed in the cold) and beer distributors. The passage of the Volstead Act suddenly transformed the largest alcohol-production center in the country into the largest alcohol-consuming area, from River to River, from Franklin Square to the Schuylkill.

It was concentrated in the Brewerytown by being illegal, and somewhat secret. Brewerytown soon turned into the Tenderloin, and the Tenderloin into Skid Row, cutting off North Philadelphia from law and order, but in time it was alarming in a different way to see speakeasies spread into other sections of the city. Much as it tried, even the Mafia couldn't control the influx of amateur criminals, when the Tenderloin essentially cut the city in half.

When the great migration from the South occurred after WW II, the immigrants turned North Philadelphia into a slum. Cutting I76 along the same center-city lines helped shrivel North Philadelphia and hustle its flight to the suburbs. Some misadventures of Philco and Ford, Baldwin and Stetson hastened the process and may have caused some of it.

|

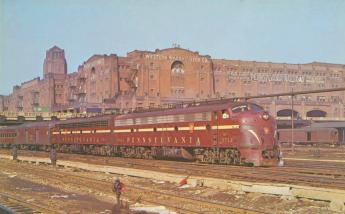

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

America grew into a mighty industrial nation as a result of becoming the Arsenal of Freedom in the Civil War and two World Wars. The nation needed to expand its industrial base from the essential monopoly corridor of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and it had the money to do so. The land was cheaper elsewhere, labor was nonunion elsewhere, and air conditioning made the South bearable. Wall Street saw an enormous opportunity to buy stock from the family partners of Philadelphia industries, and sell it again to the world. These new owners had no interest in preserving lovable Philadelphia; they wanted to reap the harvest of expanding what we had, to the rest of the country, maybe even the rest of the world.

Once a spiral like this gets started, it runs by itself. The owners of the mansions on the hills, proprietors of what were big businesses by Victorian standards, sold their partnerships, their children were converted into coupon clippers, and their grandchildren into trust-fund babies. If you really have nothing much to do, why not do it in California next to the beaches? Hollywood made trust fund babies seem glamorous on the Main Line, just as Madison Avenue had once made patriots on the left bank seem fatally attractive. Those movies and novels made somebody pretty rich, but whoever it was, doesn't live here, anymore.

Originally published: Friday, July 11, 2014; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 16, 2019