Related Topics

Obamacare: Examination and Response

An appraisal of the Affordable Care Act and-- with some guesswork-- its tricky politics. Then, a way to capture major new revenue, even paying down existing Medicare debt, without raising premiums or harming quality care. Then, an offering of reforms even more basic, but more incremental. Finally, the briefest of statements about the basic premise.

Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG), in Relation to Medical Electronic Records.

|

| The American Medical Association |

For a concept supposedly working moderately well, the Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) system for inpatient reimbursement has a bizarre history. It has led to some unconfessed, and widely unrecognized, disastrous results, and should be thoroughly reworked as soon as possible. In a scholarly sense, the story begins eighty years ago. The American Medical Association decided all of the diseases, ultimately all of the medical care would be better understood if reduced to a systematized code. Originally, the code was visualized as a six-digit complex, with the first three digits defining an anatomical location, followed by a second set of three digits specifying the cause of the disease affecting that location.

SNODO That 6-digit structure limited code to a thousand diseases in a thousand locations, or a million "disorders" just for a beginning. Roughly half those theoretical combinations have no biologic existence, although even fanciful codes had some value for detecting coding errors. Other regions of the code exceeded the number of conditions actually found to exist, but originating in a digital structure then allowed virtually unlimited expansion, but sacrificed the significance of a particular position within the code. IBM was enlisted as a consultant, who advised the AMA to stop worrying about it; just provide a numerical code for everything, in the finest detail possible. Mathematicians could later easily make it usable for calculating machines, the forerunners of computers; and non-existent conditions created no harm. Some of those consultants had worked with a system which produced great success for the U.S. Census and perceived no advantage to limiting the code numbers while planning for them to be manipulated by machines. The third group of three digits was soon added, making a nine-digit Standard Nomenclature of Diseases and Operations , familiarly known as SNODO, which could identify a million different operations, whether actually performed or not. Actually, groups of three or more digits separated into groups of three digits by hyphens transferred the significance of code-position to the cluster level, which proved adequate.

SNOMED The pathology profession subsequently added still the fourth set of digits, for microscopic features, so the potential was soon up to a hundred million microscopic conditions. The team of physicians who worked on coding the medical universe contains many names now famous, notably including Robert F. Loeb and Dana Atchley of The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. For at least thirty years, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals (an AMA and AHA joint affiliate) enforced a rule: every discharge summary from every accredited hospital in America must code and index every discharge diagnosis in SNODO code. It was tedious work, kept alive by the glittering future prospect of developing an Electronic Medical Record by 1940.

|

| Robert F. Loeb |

ICDA After twenty years or so of this enormous task, the Medical Records Librarians rebelled. The labor effort was burdensome, and the librarians were in an occupational position to observe how little use was being made of it. On their demand, an alternative simpler coding system was adopted, called the International Classification of Diseases (ICDA). At first, it was limited to the one thousand commonest discharge diagnoses , therefore limited to the charts which the librarians could confidently observe would be used. In time, it was expanded to ten thousand commonest diagnoses. Limiting medical codes also limited the cost and effort of coding and was considered an important retreat from over-enthusiasm. Meanwhile, expansion of the SNODO code by a handful of true believers continued to fill up the coding gaps, soon using and exceeding the capacity of the 80-column IBM punch card (originally, ten digits plus metadata), one card per diagnosis.

Unfortunately, the code was in danger of collapsing from this unanticipated expansion, since computers had not yet advanced to the point where they could rescue SNODO from the limitations apparent to its users. It was a classic case of a hypothetical system appearing to be better than the one in actual use, but not living up to its promise when both systems encountered actual use. The ICDA coding scheme did suffice for immediate purposes, and the "calculator" system was at least a decade away from evolving into the more flexible "computer" which could skip around the limitations of a punched card input system.

The professional difference was this: the doctors roughly understood the coding logic and could devise an understandable code for most charts through the logic of a structured language. The record librarians had not been trained to encipher (or even dither, as photographers say) the code by logic; a thousand codes was about the limit of what anyone could memorize. The burden of manual coding eventually overran the code design, before practical results could defend its utility in other areas of the hospital or the profession.

All the medical record world promptly abandoned SNODO; except for the pathologists who intuitively recognized ICDA could never approach their own greatly expanded needs. Eventually, pathologists took SDODO over, expanded and redesigned the basic framework, and produced what they are rightly proud of, an elegant codebook called SNOmed which obeyed meaningful internal coding rules. It still came, however, as a large and expensive book, which most practitioners were reluctant either to buy or to use.

|

| Dana Atchley |

DRG Meanwhile, a group at the School of Hospital Administration at Yale under the leadership of John Thompson lurched in the opposite direction of drastically reducing the ICDA code (initially expanded to 10,000 entries, which proved too large for some purposes, while still lacking specificity in many others), back down to only 468 of the commonest "diagnosis clusters". The purpose was to find clusters of diagnoses with common characteristics, which could be used by unskilled employees to identify diagnosis submissions which normally fell within certain bounds, but who in a particular case were sufficiently deviant to warrant investigation as "outsiders". This gross sorting by machine was then examined by the PSRO (Professional Standards Review Organizations), especially in the central feature of the length of stay. They termed their product Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG) , which made no pretense of being complete but was complete enough to encompass the majority of outrider events. The computer version of their concept was called Autograph, which had some attraction to hospital administrations as a way to predict outriders. To summarize what happened next when Medicare adopted DRG for payment purposes: both DRG and ICDA started to expand, and SNOMED was relegated to the role of the codebook for Neanderthal pathologists.

Two million diagnoses are compressed into two hundred payment groups.

|

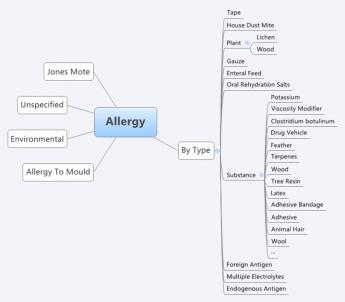

| Diagnosis "Related" Groups |

Using the standard diagnosis codes, one-size-fits-all did not help the hospital and insurance accountants a bit, since my habit they tend to believe all businesses are about the same, no matter what the business produces. Their complaint was coded with thousands of codes were too big and complicated. Simultaneously the medical professionals were finding them much too small for the job. Meanwhile, ICDA was fast losing its reputation for being compact and inexpensive, while the opposite feeling immediately developed: the DRG was far too small for what physicians could now realize was going to play a very large and important role in everybody's finances. Two vital areas of the hospital had difficulty communicating from the beginning; now, there was no longer even a common language to use. There was no quick fix, either, because both DRG and the underlying ICDA designs were based on the frequency of occurrence, rather than precision and logic. Furthermore, the copyright was owned by professional societies who had little interest in finances, and considerable interest in reducing their burdensome coding workload. In the background, however, computers had made the task of code translation a trivial one. A third profession, the computer department, scarcely knew what the other two were talking about, but they came closer to affinity with the accountants.

Like the three bears of Goldilocks, some codes were too large and some were too small, but at least there were three of them, each crippled in a different way. Comparatively few doctors understood what was going on, and in spite of their vital interest at stake, had trouble getting over their hatred of the boring coding task. Since this whole issue of data coding and summarization has taken on major importance to the success of the Affordable Care Act, in some circles the uproar has become a political war dance. Let Obama do it if he likes coding so much. Basically, the librarians were saying they resented being criticized for making important mistakes in a task they didn't understand very well. In summary, everybody hates coding.

Overview of the Future.One a faction of the small field of those who are interested in such matters has decided to expand both the specificity and the reach of ICDA, which is now up to its tenth edition of revision. Unfortunately, it does not seem to some of the pathologists to be a sensible approach. We have an elegant code in SNOMED, they protested, which is arguably too big to use; expanding ICDA seems destined to reach the same destination, on the rebound from being too small. We now have ample data on what is common. The most efficient approach would at first seem to be condensing the highly specific SNOMED to a useful size, based on the frequency of use. The approach would stand in contrast to making a list of diseases by frequency, and then subdividing their specificities. While such a condensed volume could be printed as a book, we are now at a point where every record room within the hospitals of the nation is equipped with several computers, so the elasticity of the code should no longer be anyone's problem. Let the machines do the drudgery.

This whole process could now rather easily be automated for much more than its original purpose of classifying disease populations, and in a pinch it could even substitute 26-digit letters for 10-digit numerals, imparting some clues in the process. Further condensation of an already condensed version began to be used for payment purposes, adding still greater amounts of practical nuance. You might suppose everyone could see paying the same amount of money for treating the same disease (tuberculosis, let's say) of two different organs (let's say of bone, and of the kidney) was either going to bankrupt someone or enrich someone else. And that's only money. Any scientific or diagnostic decision based on a code of "All other" will make computerized medical records sprint faster toward worthlessness. At the rate it's going, lumps of "all other" will have no relation to each other, except to justify the same reimbursement for treatments of vastly different value. Or difficulty. Or cost. Or contagiousness.

|

| SNOMED |

In automated form, SNOMED is quite ready to be revised still further in other directions for other purposes. It could, for once, integrate the accounting and demographic functions with the rest of medical care. But a great many other useful functions can be imagined, once computers have a stable platform on which to build, and the task of coding can be safely undertaken without much physician input burden. Safe, that is, from the danger, the whole coding framework will get changed, again and again. In a certain sense, this is similar to the brilliant choice by Apple of the Unix skeleton, when Microsoft Windows seized on quicker expedients. A great many sub-professions seem to wish to have their own codes for their own purposes and resist the idea a physician code should be imposed on them. When you encounter such obstructionism, it is easy to suspect motives. But the general rule is: when it comes to a choice between scheming and incompetence, it's incompetence, nine times out of ten.

However, medical care and hospital care are medical functions, and their accounting and demographics will always eventually return to their medical professional core. Meanwhile, notice what happened to DRG, a code so crude it relegates most refinements to the category of "All Other". The fact of the matter is, it is a crude approximation, some cases paying on the high side, some on the low side of true costs. If the hospital loses money on inpatients, well, just build another wing to the outpatient department. Underlying this response was the enduring misconception that outpatient care is inherently cheaper than inpatient. If it's the case, well, we'll just have to fix it.

The surprising lack of chaos from such experience has almost nothing to do with medical content, and almost everything to do with having insufficient case volume to remain in balance. That is, the big hospitals smudge it out, and the small hospitals don't understand it. The highly prized profit margin of 2% or 3% can easily be achieved by admitting slightly more cases of a profitable kind (ie hire a surgeon expert in certain profitable operations), or by the government adjusting just a few DRGs to profitable status (like reducing tariffs on behalf of favored industries in Congress). Meanwhile, the rest of the enterprise becomes progressively more expensive, because there is no fixed relationship between service benefit prices and audited costs, and now an even less regular relation, to cost-to-charge ratios.

It is a precarious thing for institutional solvency, to depend on a financial balancing of a particular caseload within one set of four walls, and then complain hospitals are too small to survive. Between their accountants and their record librarians, this outcome drives the smaller institution into a futile chase after higher patient volume. Of course, we need to change with the times. But some basic truths never change, and one of them is every ship should be able to sail on its own bottom. You don't approach that by giving every ship a new hull.

Let's get specific. In the first place, allowing only a 2% profit margin during a 3% national inflation is to walk on the edge of a dangerous cliff. If some fair profit margin could be agreed to, it is only an average among hospitals. You might as well reduce the DRG to four payment levels, and reimburse hospitals on the basis of which of the four walls the patient faces. With enough tinkering, you might arrive at the desired total hospital reimbursement to match any profit margin you establish, totally disregarding the diagnoses of all patients. Quite obviously, you must code the diagnosis to whatever number of digits it requires to identify the unique condition. You could match up all of the hundred dollar cases and all of the fifty thousand dollar cases, call the two codes, and pay only two prices.

But such an effort is just a delusion. Somebody-- or some machine-- has to go to the trouble of coding every single diagnosis down to the point where the code is no longer meaningful to costs and assign relative values among them. Only at that point would it be legitimate to assign a dollar amount to each relative value. You have to maintain the code as treatments change, which will be quite frequently. You can do it, and you can computerize it. A computerized version of this process would scarcely be any different from copying the English description and, like a Google search, getting back a number to copy; it might even be done by voice transcription. But there is still no guarantee charging itemized bills wouldn't turn out to be cheaper, and at least have a different meaning. DRG in its present form is nothing but a crude rationing system; get rid of it, or spend the money to make it work. I can't guarantee if you put a doctor in charge, it would work. But I can guarantee that if you don't put a doctor in charge, it won't.

Proposal 5: Congress should be asked to commission a computer program to translate English language diagnoses into SNOMED code, preferably by voice translation. Suggested format: a search engine where English variants of discharge diagnoses are entered, and a SNOMED code number returned, along the general lines of entering common phrases into Google and receiving file location numbers in return, except it returns the SNOMED code. If the code is not found, the computer accepts a manual entry by a trained person. verified by an expert over the Internet to become officially entered into a master list which is periodically circulated as an update. The search program and its supplements should be produced on DVD disks to be used on hospital record room computers by other professional users. It should provide "hooks" so the Snomed codes and patient identification can be transferred electronically to related programs, such as payment codes and billing.

So that's how DRG got to be what it is. It's perfectly astounding such a crudity, devised for other purposes, could be so "successfully" employed to pay for billions of dollars of Medicare inpatient care, such that payment by diagnosis-lumps threatens to spread to all medical care. There is even another way to describe it: inpatient hospital care has been lumped into a rationing system which constrains national inpatient care to a 2% overall average profit margin. That's just as surely true as if someone deliberately tried to make it that way.Payment by diagnosis ignores both cost and content, based on the mistaken assumption those features have already been carefully accounted for. It does not matter in the slightest how long the patient stays or how many tests he gets, or how many expensive big hospitals swallow up inexpensive little ones. Meanwhile, emergency rooms and satellite clinics also do not affect the cost inherent in a supposed linkage between the diagnosis and the cost. The failure to link drug prices into this modified market system is particularly noticeable.

The exciting potential has been lost to have the patients who can shop frugally as outpatients, set the price for inpatients who are helpless to act frugally. Their much more generous profit margins support what is essentially a hospital conglomerate. Any corporate conglomerate executive could tell you what happens when one department is subsidized, while another is treated as a cash cow. And the fun part is this: squeezing physician income against an unsustainable "Sustainable" Growth Rate creates the "doc fix", which annually blackmails physicians into acquiescence past the next November elections.

SGR: Sustainable growth rate, earmarks by a different name. SGR is a term borrowed from financial economics, signifying the rate at which a company is able to grow without borrowing more money. It is easily calculated by subtracting dividends from return on investment. Any variation from this definition will produce different results. A sustainable growth rate in Medicare is calculated by a formula, modified every year in special ways which closely resemble "earmarks", but contain special adjustments for changing work hour components, malpractice cost components, etc. It is a large task for the Physician Payment Commission to determine yearly changes in thousands of services, and it must be frustrating for them to see their painstaking calculations tossed aside every year by Congress, in response to howls from the various professions. Whenever this occurs it is a fair guess the calculation has been misused. The discussion has long since transformed from a simple calculation to a simple threat: physician reimbursement will be cut. Each year it is cut, and each year Congress relents on the cut at the last moment. But ultimately its design will prevail: on the pie-chart of healthcare expense, physician reimbursement will shrink, and hospital reimbursement will expand, as physicians migrate to salaried hospital employment, and enjoy an instant 40-hour week amidst a physician shortage. This keeps the AMA in a constant state of agitation, and physicians in a constant posture of supplication. At the end of 2013, the proposed cut in reimbursement had grown to 26%. When almost every physician has an overhead of 50%, a cut of 26% is beyond meaningful. And every year the financial attractiveness of joining a hospital clinic for a dependable salary grows, with consequent improvement in the overall power of the hospital conglomerate, and steadily decreasing relation to market-set pricing readjustments.

Insurance Reimbursement, The Missing Item on the Itemized Bill. The DRG system threatens patients, too. After discharge from a hospital, the patient is sent a multi-page itemized bill, which purports to be what the patient would owe without insurance. Such bills traditionally omit any mention of the insurance reimbursement, which is the only payment the hospital receives if it has contracted to accept "service benefits" as payment in full. Since that is almost always the case, the "total of service benefits" is exactly equal to the "total patient responsibility". Since the patient will pay nothing if patient responsibility is limited to service benefits, and service benefits are exactly equal to whatever the patient received, the explanation goes round and round without ever revealing what has been paid. The illusion that you have been told something worth hearing, is maintained by providing an almost endless list of itemized charges.

Most hospital employees do not have the foggiest idea why the list is even produced, and its accuracy is therefore questionable. A variety of specious explanations, therefore, emerge, usually with a focus on billing a handful of uninsured people, or insured people whose service benefits have expired as "outsiders". There may be a particle of truth to this, easily refuted by showing the supposed items on the bill were often fabricated by employees who know very well they are seldom used for anything. Most likely, the purpose is to conceal the true insurance reimbursement from competitive insurances who might undercut them. As profit margins shrink, it becomes increasingly dangerous to let competitors know what they are. As margins widen, it is even easier for competitors to undercut them. As a matter of common observation, most retailers in any business are less than forthright about their profit margins, so perhaps this concealment can be forgiven as normal commercial behavior. It becomes more questionable when seen as an industry-wide practice, intended to defend a system of double-pricing. In this case, it defends the employer tax discount as the lowest price around, when compared with those rascals, the uninsured or the insured but fully taxed.

The DRG payment to the hospital is not zero, but it is far less than the total on the itemized bill and is seldom revealed. One central message it sends is however pretty clear: "This is how much you would be charged if you didn't have Insurance X." The shortfall in revenue is made up by overcharging the emergency room and the outpatients, who are unsuitable for anything resembling the present DRG. If the hospital does not have enough outpatient work to sustain the inpatient losses, its only recourse at present is to call the architects and build a bigger outpatient department. To fill it, just buy up a neighboring group practice or two of neighborhood doctors. Fix the DRG, and it would be hard to say what would eventuate.

Bottom Line: Who is Injured? For a long time, service benefits insurance was the only thing supporting the hospital industry, and commercial behavior by the hospitals was justified as the only way to support their charitable mission. Now that Health Savings Accounts have reached 12 million clients, with assets reaching $22.8 billion, a viable way to provide indemnity insurance has definitely arrived. Not only are HSAs cheaper for the customer, they very likely provide higher payments to hospitals. This last point will only be clarified when we learn what discounts the catastrophic high-deductible insurance have been able to extract, but hardly anything else will affect the answer. To the extent one competitive method receives major discounts and the others generally do not, this service benefit discount is probably only of benefit to the insurance companies who enjoy it. A personal episode in my family illustrates.My son went to a well-known Boston hospital for outpatient colonoscopy and received a bill for $8000.00. When told that was outrageous, he protested and promptly received a bill reducing the charge to $1000. He was delighted to send a check for that reduced amount, even though I told him a fair price was probably around $300. He reminded me of a comment from a famous surgeon now deceased, whose name is emblazoned on a tall pavilion in another city. The old surgeon growled, "The only reason to carry health insurance is to keep the hospital from fleecing you." In a sense, that growl applied directly to the colonoscopy, which that hospital had converted from markup into a holdup.

Discounts for Health Savings Accounts? HSAs scarcely have to penetrate the market much further before they have the market power to command an equal discount. That may still take a little time, because some states have hardly any penetration, while California has a million subscribers. In the meantime, the patient needs to be careful to ask for prices in advance. Almost every health insurance has started to impose high deductibles, so their proper stance is to insist on equal treatment. The old system of "First-dollar coverage" was responsible for making outpatient care a target for this sort of thing. The next advance, after making all outpatient care match market prices, is to insist a hospital charge the same thing for the same service for inpatients as it does with outpatients. To make that possible, it has to return to fee-for-service billing, and management of Health Savings Accounts should settle for no less. That's the main reason DRG billing offends me, although there are lots of other reasons, and lots of other people are injured in different ways.

Originally published: Sunday, February 09, 2014; most-recently modified: Sunday, July 21, 2019