Related Topics

Obamacare: Examination and Response

An appraisal of the Affordable Care Act and-- with some guesswork-- its tricky politics. Then, a way to capture major new revenue, even paying down existing Medicare debt, without raising premiums or harming quality care. Then, an offering of reforms even more basic, but more incremental. Finally, the briefest of statements about the basic premise.

The Real Obamacare, Unveiled

|

| Democratic Speaker Nancy Pelosi |

Even loyal Congressional Democrats demanded more explanation for passing Obamacare than they received. Democratic Speaker Nancy Pelosi implausibly explained, "We have to pass the bill in order to see what's in it." That didn't help very much.

An unexpected bungle of computerized insurance exchanges that didn't work, would soon confront Obamacare supporters with explaining things to a hostile public, instead of to a merely curious one. Instead of providing better insurance to thirty million people, many of whom did not have insurance, the Administration had to cope with the possibility of uselessly depriving several hundred million people of insurance that did satisfy them. And to do so past the deadline for renewal of their old programs, made several million suddenly anxious that newer products must somehow be worse, not better.

It was expedient politics to add new but more expensive mandatory features. But since many people could already choose a more expensive policy if they craved more features, the practical effect was usually to make insurance more expensive without providing anything new. Here, it also had the unwelcome appearance of extra cost paying for somebody else's subsidy. In any event, health insurance was certainly not cheaper.

Employees of big business were evidently particularly dissatisfied, so their arrangement will be announced later, probably after the elections. Two years after passage, the Affordable Care Act was still a work in progress, but it was hard to call it a victory.

|

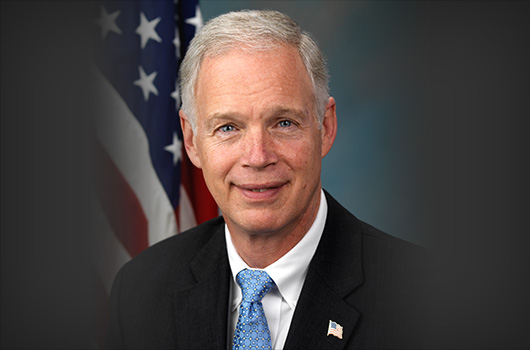

| Senator Ron Johnson |

Worse to come wasn't just an idle possibility. Millions of complacent people then received letters of cancellation (from their old, private insurance companies) in spite of specific provision in the law (section 1251) and repeated assurances from the President that this would never happen. Retired people on Medicare had mostly ignored Obamacare, which didn't apply to them. But any cancellation of existing benefits quickly revived anxiety that the real intention might be to pay for poor people (Obama's "base") with cuts in Medicare, which everyone over 65 had grown accustomed to receiving. A large new group was suddenly asking awkward questions.

Government workers and Congressmen definitely had to accept the new plans, probably to demonstrate shared sacrifice. That led Senator Johnson from Wisconsin to sue for damages because his constituency might think he really wanted to have it, in spite of nominal opposition. Big business received more extensions to its one-year postponement, which increasingly looked like a repeat of the 1994 Clintoncare experience where they had walked out, in a somewhat more obvious way. Small business was immediately refused similar relief, introducing concern about political favoritism, and conspiracies yet to be revealed. One of them surfaced a few months later, when "postponements" for employers with 50-100 employees were announced, effectively adding them to the definition of big business. Once more, there had been no such proposal in the enabling legislation. A majority of state governments refused to establish insurance exchanges, and an appreciable number of governors even refused to expand their Medicaid programs with Federal money. It could be argued that bribes that weren't permanent were essentially no different than direct coercion of states by the Federal Government, but were just a different method of revoking states rights under the Constitution.

Since it might be many years before deaths and retirements made it possible for insider biographies to explain everybody's true motive, the public applied the ancient Roman test of Cui bono? ("Who comes away from it, better off?") Everyone half expected the Obama base to be rewarded, and the Republican base to pay for it; but rewarding five percent at the expense of ninety-five percent, went beyond any election mandate, or even any tradition of the spoils system. Better medical care at cheaper prices always sounded over-optimistic. But worse care at a higher price now began to seem like the real outcome. Who comes away from that, better off?

|

| Republican Senator Scott Brown |

If a copy can be found, it certainly might be tempting to review the final original House bill and compare what was in it with the ultimate product (which was really just the Senate bill). But at that particular moment, there had been a Democratic majority, and that majority declared its preference for the Senate version. That is what the President signed. He then apparently hoped to solve its deficiencies by Executive Branch regulation, which might well lead to Constitutional lawsuit based on the "Vesting Clause" in Article 1 of the Constitution that, All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives. . When he subsequently did issue several dozen unauthorized regulations, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Boehner, announced his intention of filing a Constitutional suit in the Supreme Court. In a sense, that took matters back to Franklin Roosevelt's "Court Packing" uproar in the 1930s, with more or less the same issue of a President illegally delegating legislative power to an executive agency. This once proved to be a convulsive national issue. So this book deals with it in a later chapter, because the state legislatures got to the Supreme Court first in a related Constitutional matter.

|

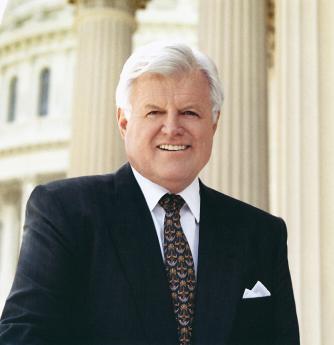

| Democratic U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy |

This uncertainty must be quickly resolved. The final law has over 450 sections, so some can be suppressed for a long time before an absence is noticed. The President's public restatement of section 1251 after the policies had already been canceled, remains particularly baffling. There are times when it almost seems the President was daring the Legislative branch to sue him. Although it is possible this maneuvering is more aimed at the Tea Party than the Democrats, it would certainly be the most dramatic Constitutional crisis since the Court-packing attempt in the 1930s. It deserves consideration in detail, but first, we must review the other Supreme Court action in the early days after passage of the Act, which may or may not have been the start of an elaborate collision of historic proportions. Preliminary conclusions must be reserved. Speaker Boehner may call off his suit after the outcomes of the 2014 Senate elections are known. International events may take a sudden turn. And the financial markets may still contain some surprises. More directly, there may be actions by the central actors in what Senators refer to as "this train wreck". In view of its potential destructiveness, the only consolation is it might at least inhibit Congress and the President from this particular maneuver a third time in the future.

Soon combined with a disastrously failed computer program for Insurance Exchanges making it impossible for the program even to get started, 2014 appears to be a bad year for tranquil discussion. It dramatized that trying to bully through was a bad choice. Millions of letters notified clients their old insurance was terminated as "inadequate" while the President continued to appear on television programs assuring such a thing would never happen, -- all of this projected a pretty poor image.Originally published: Friday, December 20, 2013; most-recently modified: Friday, June 07, 2019