Related Topics

No topics are associated with this blog

Interest Rates, Investment Income, and Inflation

|

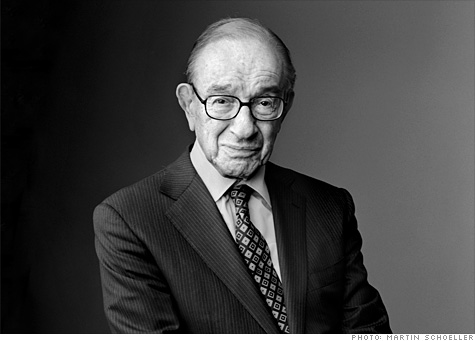

| Mr. Alan Greenspan |

When there is inflation, the value of money goes down, so you might expect interest rates -- the rental cost of money -- to go down, too. However, people anticipate higher prices, so lenders build a premium into the interest rate structure to compensate for the value of the money to be lower when it is repaid. That raises interest rates, and the Federal Reserve will generally raise them even higher to put a stop to inflation. So, buying and selling bonds is a zero-sum game, far riskier than it sounds. Consequently, there is a flight toward common stock, thus raising its price. Meanwhile, inflation usually hurts business, tending to lower the stock prices. As a consequence of all these moving parts, long-term investors are urged to buy at a "fair" price and never sell, no matter what. Even that strategy fails for any given stock because somehow corporations seldom thrive for more than seventy-five years. So, the advice is to diversify into a basket of stocks, and the cheapest way to get that basket is to buy an index fund. In a sense, you can forget about the stock market and let someone else manage the index, for about 7 "basis points", that is, seven-hundredths of a percent. All of this explains the choice suggested for Health Savings Accounts of buying total market index funds. Limiting the universe to American stocks is based on a political hunch that it reduces the chances of harmful Congressional protectionism. Having said that, a Health Savings Account must raise cash from time to time, and to guard against forced selling in a down market, some average amount of U.S. Treasury bonds will have to be maintained. Ideally, the number of Treasuries would be small for young people, and grow as they get older, and therefore more likely to get sick. Pregnancy is the one universal cost risk for younger people, and they know better than anyone what the chances of that would be in their own case.

This approach is greatly strengthened by reference to the modern theory of a "natural" interest rate, to which the whole system has a tendency to revert, if only we knew what the natural rate is. It is not entirely constant, but over time it seems to be something like 2%. If we knew for certain what it was, we could set a goal for perpetuities like the Health Savings Account to be "2% plus inflation". Since inflation is targeted by the Federal Reserve as 2%, that would amount to an investment goal of 4%. If you can buy an American total market index fund consistently gaining at 4.007 % per year, you should buy and hold. If it rains less than that, it is either run by incompetents, or it is a bargain which will eventually revert to 4.007% and pay a bonus. If, on the other hand, it gains more than that, there exists a risk it will revert to the mean. That it is being run by a genius is sales hype to be ignored. We suggest buying into it in twenty yearly installments, which should balance out the ups and downs, so then you can forget about even this issue.

But don't count the same issue twice. In order to assure a 2% real return, it is necessary to obtain 4% in the real world of 2% inflation, and the compounded income of 4% accounts for both in equal measure. A compound income of 6%, however, is two-thirds inflation / one third "real", so artificially raising interest rates to control inflation can progressively overstate the requirement, and hence overdo the deflationary intent. Conversely, when the Federal Reserve fails to raise interest rates as Mr. Greenspan did, the result can be an inflationary bubble. The central flaw in adjusting prevailing rates to current natural rates is that we do not know precisely what the natural rate is. To go a step further for immediate purposes, we are also uncertain how much deviation there is between medical inflation and general inflation. As a result, the best we can expect is to make as much income on the deposits as we safely can, and continuously monitor whether the premium contributions to Health Savings Accounts might need to be adjusted. And the safest way to do that is to have two insurance systems side-by-side, one of them a pay-as-you-go conventional policy for basic needs during the working years, and a second one whose entire purpose is to over-fund the heavy expenses at the end of life and the retirement years, permitting any surpluses to be spent for non-medical purposes. With luck, the beneficiary might retain a choice between increased premiums, and increased (or decreased) benefits.

If these calculations are even approximately close, the financial savings would be several percents of GDP, a windfall so large that mid-course adjustments could be tolerated.

Originally published: Wednesday, October 30, 2013; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 22, 2019