Related Topics

American Finance After Robert Morris

Robert Morris can be fairly said to have made the American Revolution possible.

Dislocations: Financial and Fundamental

The crash of 2007 was more than a bank panic. Thirty years of excessive borrowing had reached a point where something was certain to topple it. Alan Greenspan deplored "irrational exuberance" in 1996, but only in 2007 did everybody try to get out the door at the same time. The crash announced the switch to deleveraging, it did not cause it.

Whither, Federal Reserve? (2)After Our Crash

Whither, Federal Reserve? (2)

Philadelphia Changes the Nature of Money

Banking changed its fundamentals, on Third Street in Philadelphia, three different times.

Robert Morris: Think Big

Robert Morris wasn't born rich, or especially poor, but he was probably illegitimate. He had no recollection of his mother; his father, a tobacco trader in England, emigrated to Maryland and died rather young. It didn't take long for young Robert to become one of the richest men in America.

Unwritten Constitutional Modification

It is so difficult to amend the Constitution, we mostly don't do it. Our system is to have the Supreme Court migrate slowly through several small adjustments, watching the country respond. Occasionally we have imported new principles, sometimes not entirely wise ones, adopted without the same seasoning.

Right Angle Club: 2013

Reflections about the 91st year of the Club's existence. Delivered for the annual President's dinner at The Philadelphia Club, January 17, 2014.

George Ross Fisher, scribe.

Why Jefferson Hated Banks and Hamilton Loved Them

|

| First Bank of Philadelphia |

Some things are easier to understand when they start before they get complicated. That's true of banking, where it can now be puzzling to hear there was a strong inclination to forbid banks by law. While we were still a colony, the British discouraged bank formation, fearing strong concentrations of wealth at a great distance could lead to ideas of independence. Anti-bank sentiment was thus a Tory characteristic, although as the Industrial Revolution progressed, Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels stamped it permanently with a proletarian flavor. Large owners of farmland were displeased to see their power weakened by urban concentrations of wealth, while poor recent settlers of America wanted to buy and sell land cheaply, so they favored a currency that steadily declined in value. People with wealth have an incentive to keep money stable, but people with debts have an incentive to pay them off with cheap money. After these battle lines clarified and hardened, the debate has transformed from an original dispute about banks, into catfights about a strong currency. As Rogoff and Reinhart have pointed out, inflation is a way for governments to cheat their citizens, devaluation is a way of cheating foreigners. Naturally, politicians prefer to cheat foreigners, but national tradition curiously seems to favor one style more than another. Essentially, they are the same thing with the same motive, although outcomes may be different. One is restrained by fear of revolution, the other by fear of an international currency war.

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

While George Washington was America's first president, Alexander Hamilton was Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson was Vice President; the cabinet contained only four members. Although Hamilton was born poor, the bastard brat of a Scottish peddler in the view of John Adams, he had learned about practical finance in a counting-house, and later gained Washington's confidence on the headquarters staff; Washington eventually made him a general. Jefferson was part of the slaveholding Virginia planter elite, elegant in writing style and knowledge of art and architecture, sympathetic to the French Revolution; eventually, he died bankrupt. Early in the Washington presidency, Hamilton produced three long and sophisticated white papers, advocating banks and manufacture. Jefferson was opposed to both, one facilitating the other, which we would today describe as taking a green, or leftish position. Banks were described as instruments for accepting deposits in hard currency, or specie, and lending it out as paper money. The effect of this was a degrading of gold into paper money, or if not, an inflationary doubling of currency. Banks would be able to create money at will, a capriciousness Jefferson felt should be confined to the sovereign government. Just keep this up, and one day some former banker from Goldman Sachs would be able to tell the President of the United States, "The bond market won't let you do that." In this sense, the bank argument became a dispute about public and private power.

|

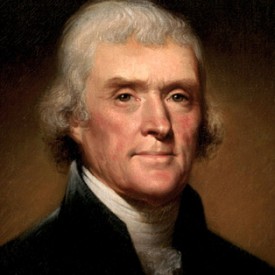

| Thomas Jefferson |

Hamilton, a former clerk of a maritime counting house, could observe that sending paper money on a leaky wooden boat kept the real gold in the counting-house even after the boat was lost at sea. To him, prudent banking transactions enhanced the safety of wealth, reducing risk rather than enlarging it. Later on, he learned from Robert Morris that a bank floating currency values on the private market disciplined the seemingly inevitable tendency of governments to water the currency. Once more, banks should enhance overall safety in spite of being vilified for creating risk. To both Hamilton and Jefferson, all arguments in an opposing direction seemed specious, designed to conceal ulterior motives.

Banks came and went for a century. By the time they almost were a feature of every street corner, banks were taking paper money (instead of gold and silver) as deposits and issuing loans as paper money, too; the gold was kept somewhere else, ultimately in Fort Knox, Kentucky. With experience, deposits could stay with the bank long enough that only a rare run on the bank would require more than 20% of the loans to be supported by physical ownership of gold. By establishing pooling and insurance of various sorts, banks persuaded authorities it was safe enough for them to hold no more than 20% of their loan portfolio in reserves. By this magic, loans at 6% to the customer could now return 30% to the bank. A few loans will default, a reserve for defaults was prudent, so the bank with a 2% default rate could settle for a 20% return rate. A bank which was deemed "too big to permit it to default" was invisibly and costlessly able to trim its reserves, and thus receive a 25% return by relying on the government to bail it out of an occasional bank crisis. With this sort of simple arithmetic, it is easy to see why multi-billion dollar banks were soon arguing that 5:1 leveraging was too small, a reserve of gold and silver was unnecessary, and the efficiencies of large banks were needed to compete with big foreign banks. By the time of the 2007 crash, many banks were leveraged fifty-to-one, which even the man on the street could see was over-reaching. The ideal ratio was uncertain, but 50:1 was certain to collapse, probably starting with the weakest link in the chain.

|

| Alan Greenspan |

This brings banking arguments more or less up to date. Except in 1913, an "independent" Federal Reserve Bank was created. It was a private reserve pool balanced by a public partner, the government. In time, the need for gold and silver was eliminated entirely, by the wartime Breton Woods Agreement, and the Nixon termination of it. The predictable inflation which could be expected to result from a world currency without physical backing was prevented by allowing the Federal Reserve to issue, or fail to issue as necessary, the currency in circulation. This substitution was deemed possible by having the Fed monitor inflation, and adjust the flow of currency to maintain a 2% inflation rate. Although 100% paper money was an historic change, it has endured; it has withstood efforts by the politicians to re-define inflation, undermine the indices of its measurement, and brow-beat the vestal virgins appointed to defend the value of the dollar. The old definition of money has changed: it is no longer a store of value, it is only a medium of exchange. The store of value is a nation's total assets. Jubilant politicians have added an additional burden of preventing unemployment, to the original one of defending price stability. In practical terms, the goal is defined as maintaining a 2% inflation rate, while achieving a 6.5% unemployment rate. It remains to be seen whether the two goals can exist at the same time, particularly if the definitions of inflation and unemployment become unrecognizably undermined.

And it even remains to be seen whether the black-box system can be undermined from within. The Federal Reserve is so poorly understood by the public that his enemies now accuse Alan Greenspan of causing the present recession. It is argued that the eighteen years of banking quiet which his chairmanship enjoyed, was only gradual inflation, deeply concealed. It is contended that the unprecedented steady rise of the stock market during those eighteen years was financed by a small but steady loosening of credit by the Federal Reserve. Perhaps what this means is: the definition of inflation must be tightened so its target can be made and adjusted, not to 2%, but to some number slightly less than that, measured to three decimal places. Or that the 6.5% unemployment target must be jettisoned in order to preserve the dollar. With that prospect including international currency wars as its corollary, it will be an interesting debate, and immigration policy is related to it. Because one alternative could become the abandonment of the fight against inflation, in order to sustain the new objective of reducing unemployment, Jefferson would have won the argument.

REFERENCES

| The History of the United States: Course 8500, 15 Hamilton's Republic: ISBN: 156585763-1 | The Great Courses |

| This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly: Kenneth Rogoff, Carmen M. Reinhart: ISBN-13: 978-0691152646 | Amazon |

Originally published: Thursday, February 14, 2013; most-recently modified: Sunday, July 21, 2019