Related Topics

Right Angle Club 2012

This ends the ninetieth year for the club operating under the name of the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia. Before that, and for an unknown period, it was known as the Philadelphia Chapter of the Exchange Club.

Which is Better: Big Nations or Small Ones?

BIG nations easily gobble up small ones, so small ones band together. As George Washington famously observed, when you are strong the others leave you alone. But other forces make smallness seem attractive, especially if the nation is already uniform in religion, language and culture. Most nations search for an ideal size for both Peace and Prosperity and find they need two different sizes, and have to choose. Both the American Revolution of 1776 and present struggles of the European Union fit a common formula: banding together for military security, then pulling back for greater independence. The American experience of a subsequent Civil War eighty years later suggests the margin for error is narrow.

|

| Europe Colonies |

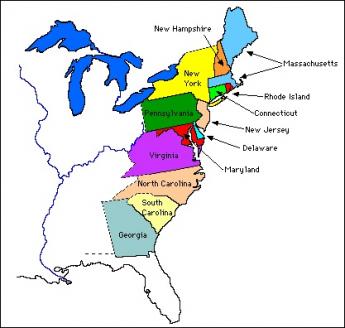

Geography doubtless imposes limits for both peace and prosperity. Some nations have therefore banded together for military reasons then split apart in local quarrels, more or less regularly. The thirteen American colonies had been afraid to confront Britannia alone, but somewhat overconfidently took on that challenge as a confederation of thirteen. At the other extreme, little Rhode Island even refused to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention, for fear the other twelve would want to share its revenues from the coastal road through their state. Similar possessiveness has at least not been reported about the narrow defile through the northern end of the equally small State of Delaware, but one glance at a map is sufficient to expect similar restlessness from the region which for decades protected its secrets of mushroom cultivation. Peace and prosperity: getting bigger discourages predators, but getting smaller offers sole possession. Since the United States grew in jumps through most of its history, it probably learned intangible things from its alternating episodes as too big and then too small. Frederick Jackson Turner's thesis of the frontier as a shaper of culture is fairly similar.

|

| 13 Colonies |

When ideas of Union first gained traction, both the thirteen American colonies and the twenty-five nations of the Eurozone were afraid of war. The American objective was the simple one of military parity with a common enemy. The nations of the European Union had a longer view; a seemingly endless history of bloody wars sustained their conviction that other wars would inevitably follow unless they did something innovative. National unification on the American model would be ideal, but perhaps the habits of cooperation and trade would lead to that. The unexpected decline of the Soviet empire further reduced the threat to European peace. Pride may also have led to over-reaching; twenty-five is comfortably larger than thirteen, which up to that time was the largest nation merger to survive. But twenty-five is smaller and thus more manageable than the present American fifty. To begin the Euro process with monetary union might produce quick benefits from a source too mysterious to produce much public resistance. Nobody could think of a war started by a monetary dispute.

|

| Justice Blackmun |

Of course the Europeans would expect to cope with the difficulties of speaking many languages. The American colonies mostly shared a single language. Even their enemy spoke English. In this particular, the Europeans seem to have underestimated the language-induced difficulties of maintaining a common understanding of what their Constitution meant to people. Indeed in American Judicial disputes about Original Intent, we repeatedly encounter the tenacity of people to believe a document says what they want it to say. Staying within a single English language, the inflammatory evolution of U.S. Supreme Court interpretations often turns on subtle differences in the meaning of simple words, since vigorous legal advocates think they are paid to marshall every argument weak or strong. Penumbras and emanations from the word "Privacy" in Roe v. Wade force our judges to decide whether the inclusion of abortion within a right of privacy is simply too far from common understanding of English, in a double sense. Both in the discovery of a right to privacy within a document which does not use the word and in the inclusion of abortion within that, Justice Blackmun clearly overestimated the capacity of citizens to understand what they did not want to understand. How much more surely would he have overestimated public willingness to grasp his meaning in two-step translations from a foreign language. Since this famous decision is destined to stand or fall, depending on public tolerance for such wordplay, having almost every citizen confidently understanding English is a decided advantage in achieving consensus about its wisdom. It seems almost unnecessary to point out how many European languages are derived from Latin or German, and how seldom such migrations of meaning have sharpened the precision of the originals.

|

| Auto-de-fe |

By contrast with important language confusions, "hatreds between nations" are often mentioned as an obstacle to unification but seem largely bogus. Argot and slang are commonly invented to conceal the opinions of a minority group. Over thousands of years, this purpose of "jiving" a secret code among conspirators has been perfected exquisitely. It's hard to overcome, easy to teach children. But the memory of actual wars really dies out rather quickly, not least because atrocities are so hideous, mankind wants to forget them. I was seventy years old before someone told me I had ancestors burned at the stake. By whom? By someone who has also been dead for four hundred years, not likely to seem threatening. Over the fifty years since the Second World War, I have run into former German and Japanese soldiers; they now seem pretty benign. One American former prisoner of war was forced to stand at attention while his Japanese captor pulled out his gold teeth with pliers; he told this story with a faint smile. It is one of the benevolence of biology that we are born without memories, and a second is the impossibility of remembering the feeling of pain without first dramatizing the experience for future reference. Once actual onlookers stop grinding the grievance ax, it should be possible to get on with devising a European constitution, provided it contains the equivalent of our First Amendment.

From a commentator's perspective, currency matters are difficult to understand and explain. For contrast, the Battle of Normandy is thrilling and awe-inspiring; every death is the death of a hero. But rises in productivity, the risk implications of volatility, even the way the value of bonds goes down while their interest rate rises seem hopelessly confusing to a beginner. Worse still, there exists real uncertainty. We now have currency which has no backing in precious metals and is really just a book entry. That's useful for transactions but certainly less useful as a storehouse of value. Mr. Ron Paul ran for President of the United States challenging the whole Federal Reserve concept, and a possibility must be admitted that he had a grain of truth in his speeches. We trust our bankers to devise a workable system of exchange without gold and silver, and readily admit that Mr. Bernanke knows more than we do. But. The world economy nearly collapsed utterly a few years ago, and you know, Mr. Ron Paul might just have a valid point or two. There has not yet emerged any fit environment for enjoying a monetary Crusade to a World Without War. For striking contrast, go to any Civil War movie and watch those teenaged soldier boys charge up the hill, ready to die for the Union.

Originally published: Tuesday, December 04, 2012; most-recently modified: Friday, June 07, 2019