Related Topics

Robert Morris: Think Big

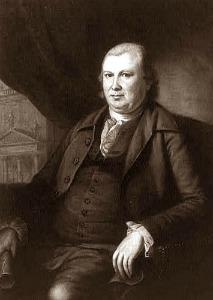

Robert Morris wasn't born rich, or especially poor, but he was probably illegitimate. He had no recollection of his mother; his father, a tobacco trader in England, emigrated to Maryland and died rather young. It didn't take long for young Robert to become one of the richest men in America.

Robert Morris, In Charge By Popular Demand

Robert Morris was in charge of the nation's finances (his title was Financier) for two intervals following two landmark emergencies: the Battle of Fort Wilson was one, and the threatened mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line of the Continental Army was the other. There was an interval without Morris in office in 1780. Both emergencies grew out of monetary panics, so a financial leader seemed a natural choice. Morris was in fact in charge of almost everything non-military, for the peculiar reason that we had no designated chief executive. The Continental Congress had a President, but the activities of the country were actually run by congressional committees. Morris wasted no time replacing this system with permanent departments under his supervision, so it is not too much to say his wartime role was acting chief executive. The improved efficiency of this approach was so evident the Constitutional Convention of 1787 seems to have spent little time arguing against continuing it, although lurking anti-Federalists never got over the idea that something had been put over on them. For reader convenience, we here take mild liberties with the chronology of individual initiatives, preferring instead to center around the two crises. The first of these, immediately following the Battle of Fort Wilson, was worthless paper money ("not worth a Continental") inflation, with soaring prices, futile price controls, and consequent false shortages of necessities. The second episode followed the later near-revolt of the Continental Army, and it was essentially a deflation provoked by the French running out of money to support us, and real shortages of necessities. Here, Morris had to cope with the end of the war in sight, but in fact not ending. Everyone was reluctant to fight battles without military purpose but unable to return to farming. Credit and hard currency reserves were exhausted. At the same time British, French and American politicians connived for advantage after a war each had failed to win militarily. By this route, having earlier described the creation of modern banking, we arrive at the cluster of clever expedients which Morris handled like a juggler as he raced from inflation to deflation, and back.

|

| Robert Morris, Financier |

The revolt of the Pennsylvania Line, along with Washington's clear sympathy for his soldiers, threw the Continental Congress into a panic. Their own responsibility for the crisis, as well as their lack of any clear idea about what to do about it, were as obvious to the public as to themselves. The approaching result went beyond a mere disgrace, and might even lead to a dictator, or God saves us, another king. A decade later, this crisis might have suggested to some that a guillotine should be set up behind the State House on Chestnut Street. Indeed, Thomas Jefferson made some remarks which might be taken in just that way. The soldiers themselves put an end to that sort of wild talk. British General Clinton sent some emissaries to the American Army, looking around for some deserters to turn Tory. The soldiers promptly executed the emissaries. George Washington, Morris' best friend, played his ambiguous position like a master. He was ultimately responsible for maintaining order, but his sympathies with the soldiers' complaint were obvious. Calling the officers together, he made the theatrical gesture of pulling off his glasses, intimating that he was going blind in his nation's service. Since his eyes served him very well for the next decade, that was unlikely. Although it is possible he believed what he was saying, most certainly the officers did.

What helped the perplexing monetary situation most was the ready availability of a financial genius to turn it around; there was no real need for others to understand it. Robert Morris had made his pile, probably the richest man on the continent, and he had the grievance of having been rejected from office after the Battle of Fort Wilson. He also had the perfectly normal motive of wishing to hold things together until the Paris peace negotiations could restore order. He had some novel plans which he wanted to try; it is not too much to surmise he wanted to show them off, particularly since their central feature would require his prodigious energy, applied to his seemingly unlimited succession of ingenious solutions. No one else even came close.

At this critical moment, Morris played coy. He was not so sure he would accept the office of Financier, a term newly invented for the occasion. Accepting Ben Franklin's cynical assessment of the future, he wanted everyone to be clear that he was going to retain his private partnerships. And he insisted on his right to hire and fire anyone he pleased within the government bureaucracy who was concerned with public money. He would accept responsibility for new debts of the government, but not for old debts which were incurred before he took office. He would delay taking the oath of office for a few months. These conditions generated a storm of opposition in Congress; Morris was serene about that, and Congress finally agreed to his terms. Most of these terms had an obvious purpose, making no secret of his distrust of Congressmen. However, the opposition might have hardened its position if the purpose of delaying the oath had been fully expressed. Morris wanted to delay becoming a federal officer in order to delay resigning from the Pennsylvania Assembly. During the interval, he applied the same power tactics to the Legislature, ending up in charge of administering state finances in parallel with his federal duties.

|

| Yorktown: Oct. 19, 1781 |

The purpose was soon to emerge, as just one instance of a general approach. As inflation tossed and turned the finances of just about everyone, Morris would buy with one currency and sell with the other, taking advantage of transient fluctuations in their respective values, then quickly reverse the currency transaction when the advantages shifted. He arranged with the French and Spanish ministers to keep their loans and foreign aid in separate accounts, doing the same thing with state accounts, and even near and distant counties within Pennsylvania. He thus had his choice of a number of currency values at any one moment. His far-flung commercial network supplied him with more precise information than his counterparties could get, and usually more quickly, so his trading activities were quite profitable. One rather extreme example was the arrangement with Benjamin Franklin in Paris; he would write checks to Franklin in one currency while Franklin would write identical deposits back to him on the same day but a different currency. He thus expanded ancient practice among international merchants. Carrying it over to government operations had the effect of creating a modern currency market. To outsiders, however, particularly his political enemies in Massachusetts and Virginia, it looked fishy. To modern observers, the astonishing thing was his ability to keep such complexity in his head. The political class which even today sees it as natural that governments might want to manipulate currency as they please would regard Morris strategies as reprehensible. Those who believe the market price is the true price however, must applaud this strategy for forcing manipulated prices back to market levels. Since here has rested a central dispute in American politics for two centuries, Morris must at least be credited with inventing the dispute. One would normally suppose that doubling the silver price of American currency in two months would vindicate this trading strategy; but it has not, suggesting the nature of the opposition has been more ideological than economic.

Within days of assuming office, the "legal tender" laws were repealed, stripping government of the ability to force its citizens to accept the worthless currency, impose rationing and price controls or otherwise assume the pose of "sovereignty". Like a miracle, food began to reappear in the Philadelphia marketplace at a lower price, and confidence in the competence of government began to return. To whatever degree the British ministry had been deliberately stalling the peace talks in the hope of American collapse, even that incentive abated.

The list of financial innovations which Morris produced in a remarkably short time, is seemingly endless. He was central in the creation of the first American bank of the modern sort, the Bank of North America. And somewhere in the welter of activity appears to be the recognition of the so-called yield curve. Loans for a few weeks or months command a much lower interest rate than long-term loans; in the colonial period, almost all loans were for six months or less. Morris seems to have realized early that great profitability could be achieved by stringing a series of short loans into one long one. He thus devised a number of strategies which had the general effect of linking short loans together. Using the remittance for a transatlantic cargo in one direction as payment for the return cargo on the same ship was an early example. Once you grasped the idea and did it deliberately, long sequences of linked loans began to appear. Just to complete the thought, it might be noticed that globalization reverses the process with shorter-term loans for components rather than longer-term loans for the entire assembled product. With lower interest rates, prices can be reduced, unless a choice is made to increase the profits.

There's one last issue in Robert Morris folklore: Did he finance the Revolution out of his own pocket? The answer is surely no because Beaumarchais ended up spending much more than any other individual, although involuntarily. The degree to which hard currency originated with the French, Spanish and American governments is a little unclear, and war damages are impossible to summarize. There were moments when Morris did personally finance major cash shortages, adding the considerable advantage of speeding up what could be a cumbersome process of budgeting, committee consideration, disputes, and hesitation. Where it was feasible, he sought restitution. Every bureaucrat has experienced delays and obstructions he wished he could eliminate by simply paying for it himself; Morris had the advantage that in an extremity, he could afford it.

The more important contribution was his pledge to make good. Creditors generally preferred his credit to that of the government; his pledge was to make good if the government defaulted. His position was that of reinsuring government debts, or in modern terms offering the equivalent of a Credit Default Swap. If we lost the war and our debts defaulted, Morris would have lost everything he had. But short of that, his pledge would result in much smaller losses. The public couldn't be expected to understand all that, so some simplified explanations were understandable. There were probably a number of similar examples, but near the end of the war, there was a particularly clear one. The Continental Army was very close to revolt when it looked as though Congress would disband the soldiers without paying them; there was no money to pay them but demobilization would likely send rioting soldiers through the countryside. Morris came forward with a million dollars of his own money and saved the day. Washington was forced to make emotional speeches appealing to the patriotism of the troops, but with most of the army barefoot, that was not likely to suffice. Under those circumstances, to come forward like Arthur Lee and remonstrate that Morris had once refused to sign the Declaration of Independence, was ingratitude of the meanest sort.

The accusation made after the war was that he profited from government losses, but there has never been any evidence of that. His position was that he came out about even. Unspoken in these quarrels was the plain fact that until he got involved in the real estate boom, he didn't need to cheat. Probably didn't have time for it.

The Revolutionary War continued for two years after Morris took office, so war losses continued in spite of improved financial management. Both the French Government and the American one were at the edge of bankruptcy. Britain was also in political chaos, but it was small consolation that Parliament had granted Independence to the Colonies when George III was adamant and intransigent in his opposition to any such idea. Strengthened by the British defeat of the French Caribbean fleet, the capitulation by the Spanish about Gibraltar, and great uncertainty about the Crimea and India -- almost anything was possible. Eventually, matters were deteriorating again. The British had the financial strength to hold out much longer, but the neglect of other opportunities eventually wore them down. Morris seemed to be winning, just by not losing.

In the midst of such anarchy, Morris had to admit his greatest failure as the Financier but was already formulating his plan for setting things on their feet. The Revolutionary War as seen by a financier had either been won by the British system of taxation or else lost by the American and French lack of such a system. It was irrelevant whether the War was described as a defeat for Britain or a victory; in Morris' view, the British had a good system and we had a poor one. No nation can finance a major war out of current receipts; you had to borrow. Your security for the loan was the economy of your nation. Even if your illiquid assets were adequate for the war, the banking markets regard your ability to pay cash for the interest on the loan as the only reliable test of your solvency. That is, a nation at war must have the ability to keep the bankers happy with regular interest payments. For that, a nation had to have a proven system of reliable taxation. Britain had it, and the American/French alliance didn't. Franklin's masterful diplomacy was just lucky enough to achieve permanent independence, but that wasn't good enough, we had to have a Federal tax system. And to achieve that, we had to have a new Constitution. Never mind that resentment about British taxes got us into this mess. Never mind the chaos of the Treaty of Paris. Never mind the war-weariness, bitterness, and destitution of the troops. Never mind that Morris was about to embark on one of the most mind-boggling real estate ventures in history, was going to go to debtor's prison, was going to engage in millions and millions of dollars of borrowing and restitution. Never mind. We needed a new Constitution, and we were going to get one. Think big.

Originally published: Thursday, June 23, 2011; most-recently modified: Wednesday, June 05, 2019

| Posted by: cheapoair discount | Feb 13, 2012 9:46 AM |

| Posted by: esalerugs | Feb 13, 2012 9:24 AM |