Related Topics

Robert Morris: Think Big

Robert Morris wasn't born rich, or especially poor, but he was probably illegitimate. He had no recollection of his mother; his father, a tobacco trader in England, emigrated to Maryland and died rather young. It didn't take long for young Robert to become one of the richest men in America.

Robert Morris and America

Robert Morris was an energetic problem-solver. In solving those problems he devised some innovative solutions which have become such axiomatic principles of a republic and its economics, that his name is seldom associated with them.

Robert Morris Invents American Banking

The finances of our new nation were subject to many violent swings from the day the British abandoned Philadelphia in 1778 right up to the end of the war in 1783, but things steadily turned for the better after Robert Morris took charge of the Department of Finance in 1780, and particularly a year later when he was given the confusing title of Financier. Those two-mile stones could be marked in another way; with the establishment of the Bank of Pennsylvania in 1780, and then a year later the Bank of North America. Both institutions were products of the Morris imagination, matching the evolving state of his thinking. But the politicians only permitted these innovations after bitter battles, so in a sense, they matched what he could accomplish politically, in two steps grudgingly forced on him by the world's reluctance to trust his ideas. It remains unclear which innovations originated with Robert Morris, and which ones were derived from the Swiss economist Jacques Necker, who had become the French Minister of Finance, or Adam Smith whose Wealth of Nations was published in 1776. There were obvious similarities in the approach of these men, and a means of communicating existed through Silas Deane in Paris. Curiously, Necker was primarily famous in Europe for shrinking the bloated and corrupt bureaucracy of French financial administration. It is not irrelevant that whenever clear thinking replaces floundering, waste and abuse begin to subside.

|

| The First Pennsylvania Bank |

The Pennsylvania Bank of 1780, unrecognizable today as a "bank", resembled a modern bond fund, operated as a partnership. It initially raised 300,000 pounds mainly from wealthy merchants, in return for interest-bearing 6-month notes. That money was promptly used to buy 500 barrels of flour for the troops at Morristown NJ. The bank thus served to transfer private funds to public purposes, which was what a rich nation urgently needs when its troops are starving.

It is always difficult to propose new ideas; in this case Morris also had to overcome resistance to taxes, which many citizens thought the Revolutionary war was all about. Taxation is, undeniably, a form of confiscation. When danger is clear at moments of panic, voluntary contributions may suffice; it is then almost sufficient to pass the hat. Soon enough, however, the government needs to increase incentives to induce the public to take the risk, hence interest rates offered by the bank must become market-driven, responding to negotiated public opinion. In short catastrophic wars for survival, a nation can gambles all its resources heedlessly. But steadily financing an eight-year war ultimately becomes a constant search for acceptable ways to transfer enough private wealth to cover the military effort, but not enough to stir up inflation. Floating interest rates, ultimately based on prevailing public opinion, do offer a match with changing prospects for victory or defeat, but only when they are not tampered with. Mismatches between public opinion and interest rates might seem tempting short-cuts to government, but they lead to inflation, price controls, rationing, and shortages of goods.

There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain of success, that to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.

|

| Niccolo Machiavelli --The Prince |

In the United States in 1780, a huge disparity between the sudden wealth of privateers, and the abject poverty of Washington's army provoked trouble. At a time when the army was barefoot, Robert Morris' personal wealth was estimated at eight million dollars, but it seems likely the contrast between barefoot soldiers and free-spending privateer sailors was even more divisive since recruitment preferences were affected. The government tried many things: inflation default, devaluation default, confiscations, and even a few timid taxes. That duty was even proposed in Congress to be levied on the prize captures of privateers, suggests the public was alert to windfall profits. But it seemed oblivious to the principle that if you tax something, you get less of it; Congress was effectively proposing to punish the capture of British ships.

The idea of some sort of bank first came to Robert Morris less than a week after he stepped forward into the rioting streets to offer ten thousand pounds of his own money for assistance to the army, and induced several dozen of his friends to be similarly generous. It was not only necessary, but it was also nation-saving. In the previous ten months, the Continental dollar had been devalued forty to one, and then later 65 to one. No one would trust such a currency, whose consequence was certain to be a military disaster. But Morris obviously also knew that winning a war run by private subscription was unlikely to last much longer than one which depended on inflated paper currency and price controls. Petaliah Webster, a brilliant economist for the day, published pamphlets sarcastically comparing price controls to the religious conversion of a prisoner on a torture rack.

Therefore, passing the hat was also only an expedient. A week later Morris reorganized the concept to be The Pennsylvania Bank, where variable interest rates would induce reluctant lenders to lend. It was perhaps one or two steps better than losing the war, but it was primitive and limited. So, although Morris had originally opposed the war for independence, and the public certainly wasn't thrilled with taxes, market-driven interest rates were about all the Continental Congress would tolerate, as a compromise between confiscation and begging. The principle of free-market interest rates worked, in the sense that the army was able to fight on for several more years, but ultimately the soldiers revolted for lack of pay. It was notable that the Pennsylvania Line led the mutiny, or protest march, from Newburgh NY to the doors of Congress, and George Washington came close to giving the troops his tacit approval.

|

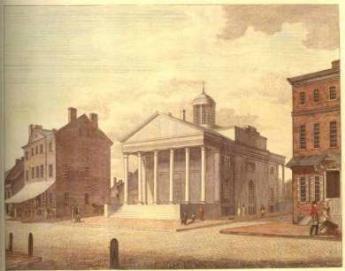

| The Bank of North America |

Well before matters came to that crisis, The Bank of North America, similarly attracting risk money by paying interest, was established in 1781 with an additional feature of generating side revenue through commercial 30-60 day loans. It was brilliant politics since Congress (with difficulty) agreed to permit a private company to engage in commerce but would never have tolerated the government doing so. When the goal is to transfer money from the private sector to the public one, the public insists on the ability to limit the amount. Otherwise, the transfer is a confiscation. Morris soon realized there was a missing third step. If the wealth of the nation was pledged to repay the war debts, creditors would insist on knowing the government's plans for repayment in case the bank couldn't do it. With the states retaining the right to tax but refusing the Federal government the right to tax without permission, the bonds of the Bank of North America were riskier for investors than they needed to be. In the difficult later years of the war, dependence on French loans began to look unwise, so the inability of the Federal government to confiscate private assets began to worry creditors. Somehow, Morris seemed to think the unratified Articles of Confederation were the problem and forced their ratification five years late. It didn't help matters, however, finally making it clear that the debt problem could not be solved without a new Constitution. When the soldiers did start to revolt, it became absolutely necessary to do something. Ultimately, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was the result. In the meantime, the United States almost did collapse after the Battle of Yorktown (1783), and the French Revolution of 1789 is plausibly blamed in large part on our failure to repay the huge French financial support of our independence. A nation which pledges its full faith and credit behind war bonds must somehow convince its creditors that it intends to repay its bondholders, almost as fully as it intends to survive the war.

of pledging the full faith and credit of the nation through imposing taxes as lender of last resort. You don't need to pay for the whole war with loans, but you do need to reassure creditors that you will tax to repay your debts rather than default on them. That is, loan repayment is placed "ahead" of taxation. If even that structure proves inadequate, well, your war is simply not winnable because it provokes a dissolution of the government. The American public in 1781 did not need to understand the logic; it had just watched the process in grisly action. The public would not accept banks backed by federal taxation except as a wartime expedient, and therefore Robert Morris failed in his most important proposal. Although he continued to press for this essential feature for nine more years until it finally succeeded, a second near-miracle was that he kept the nation solvent in the meantime. He achieved this with a breath-taking combination of expedients, energy, ingenious fixes, and bluff. But the Treaty of Paris did not come a day too soon. In characteristic fashion, he did a quick about-face and proceeded to manage a huge personal fortune during a post-war convulsion.

In late 1779, before Morris would accept the job of rescuing the finances of the floundering new Republic, however, he meant to set some things straight. Congress must therefore first agree:

-- That Robert Morris would not accept the job unless Congress agreed that he could retain all of his private partnerships. Ben Franklin had warned him how ungrateful the public could quickly become, and what a short memory it had for those who performed favors. The Congress was infuriated by such demands, but Morris was adamant. Lucky for him that he was, because his enemies soon emerged with that age-old question, "Yes, but what have you done for us, lately? " -- That Morris has the power to dismiss any and all persons concerned with public finances and the public tender laws, for a cause. --That it was acknowledged that he assumed responsibility only for new debts, not those which preceded his taking office. -- That he has the right to delay taking the oath of office, retaining his seat in the Pennsylvania Legislature, until the relationship was clarified to give him effective control of state finances.

It can be imagined how displeased the Congress was with these high-handed stipulations, but they agreed to them.

Within three days of assuming office, -- Morris announced plans for the Bank of North America, our first true bank. -- Asked two personal friends, Thomas Lowrey, and Philip Schuyler, to buy one thousand barrels of flour on their own credit. He added, "I must also pledge myself to you, which I do most solemnly as an Officer of the Public. But lest you like some others believe more in private than in public credit I hereby pledge myself to pay you the cost and charges of the flour in hard money." -- Argued eleven points against the issuance of more paper money, particularly its requirement to be accepted as legal tender: "Because the value of money and particularly of paper money, depends upon the public confidence, and where that is wanting, laws cannot support it, and much less penal laws. . . Penalties on not receiving paper money must from the nature of the thing be either unnecessary or unjust. If the paper is of full value, it will pass current without such penalties, and if it is not of full value, compelling the acceptance of it is iniquitous." -- Arranged for the sale of western lands, to raise money. -- Acknowledged the Army was owed its back pay. -- Changed the War, Marine, Treasury, Foreign Affairs from committees of Congress to permanent departments.

Originally published: Wednesday, April 13, 2011; most-recently modified: Tuesday, June 04, 2019

| Posted by: Bubbie | Apr 22, 2011 11:37 PM |