Related Topics

Quakers: All Alike, All Different

Quaker doctrines emerge from the stories they tell about each other.

Railroad Town

It's generally agreed, railroads failed to adjust their fixed capacity to changing demands. It's less certain Philadelphia was pulled down by that collapsing rail system.

It's generally agreed, railroads failed to adjust their fixed capacity to changing demands. It's less certain Philadelphia was pulled down by that collapsing rail system.

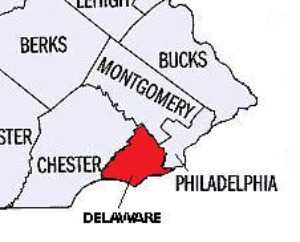

Delaware County, Pennsylvania

.

Quaker Business

New topic 2016-12-04 04:11:17 description

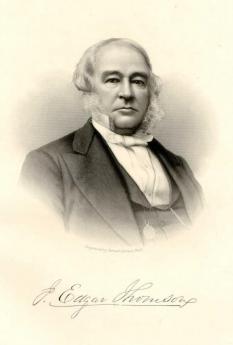

J. Edgar Thomson, Pres. PRR 1852-1874

|

| J Edgar Thomson |

The third president of the Pennsylvania RR converted a local Philadelphia line into a national railroad, the largest corporation in the world. Thomson, born in the Quaker country of Springfield, Delaware County, was the son of a chief engineer of the Delaware-Chesapeake Canal and had worked closely with his father. After an introduction to the rail business, he worked on four other railroads before joining the Pennsy at the age of 29. The State of Pennsylvania had by then constructed a series of unsuccessful canals along most of its important waterways during the Whig days of faith in government, but Thomson knew canals very well and recognized that their rights of way were best transformed into rail lines. By acquiring these unprofitable companies, he rapidly changed the PRR into a state-wide rail network, of which the famous Horseshoe Curve at Altoona was the most notable achievement. From there he moved to convert wood-burners into the coal-burning locomotives developed in Philadelphia and shifted from iron rails to steel ones. The probably unexpected effect was to convert all railroads in the nation into customers of steel and coal, Pennsylvania's main resources. Andrew Carnegie was so pleased he renamed his main steel company into the J. Edgar Thomson Works.

|

| Steam Engine on The Horseshoe Curve |

Thomson was quiet and conservative, never engaging in the high-jinks so characteristic of the rail barons of that day, leasing land rather than buying it whenever possible, expanding steadily but methodically, and never confusing revenue growth with profits. By 1870, Pennsylvania had expanded to a Jersey City terminus at New York harbor, and Chicago and St. Louis at the western ends. Within Pennsylvania, the line had expanded from 250 miles of track to over 6000. It was the largest corporation in the world. Underneath all this expansion was the Thomson system of decentralized management, essentially consisting of giving local control to division superintendents, but standardizing the corporation to superior approaches as they surfaced among the networked superintendents. His was a brilliant synthesis of the precision of an engineer combined with the cooperative sharing of a Quaker meeting. It was easy to describe but difficult to imitate, particularly by executives who boasted lifelong avoidance of the approaches of both the engineering profession and the cooperative diffident Quakers, in favor of swashbuckling, overborrowing, and muscle -- so popular at the time of the Gilded Age.

Thomson's fortune grew to seven or eight million dollars. While that was both comparatively modest by railroad standards and yet extremely affluent for the times, at his death, he had mostly given it to charity.

Originally published: Thursday, October 21, 2010; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 22, 2019

| Posted by: ray leneweaver | Oct 22, 2010 1:50 PM |