Related Topics

Outlaws: Crime in Philadelphia

Even the criminals, the courts and the prisons of this town have a Philadelphia distinctiveness. The underworld has its own version of history.

Franklin Inn Club

Hidden in a back alley near the theaters, this little club is the center of the City's literary circle. It enjoys outstanding food in surroundings which suggest Samuel Johnson's club in London.

Revisionist Themes

In taking a comprehensive view of a city, an author sometimes makes observations which differ from the common view. Usually with special pride, sometimes a little sullen.

Government Organization

Government Organization

Shaping the Constitution in Philadelphia

After Independence, the weakness of the Federal government dismayed a band of ardent patriots, so under Washington's leadership a stronger Constitution was written. Almost immediately, comrades discovered they had wanted the same thing for different reasons, so during the formative period they struggled to reshape future directions . Moving the Capitol from Philadelphia to the Potomac proved curiously central to all this.

Customs, Culture and Traditions (2)

.

Thinking About Thought

There's a yawning gap between concepts of the mind, and concepts of brain function.

Original Intent and the Miranda Decision

|

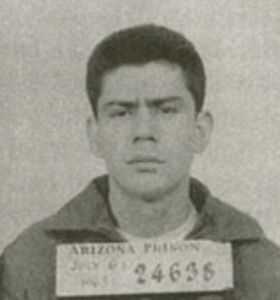

| Ernesto Arturo Miranda |

At the lunch table of the Franklin Inn Club recently, the Monday Morning Quarterbacks listened to a debate about Guantanamo Bay, prisoner torture and police brutality; all of which centered on the Supreme Court decision known as Miranda v Arizona. Ernesto Arturo Miranda was convicted without being warned of his right to remain silent, sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison in 1966. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court, with Chief Justice Earl Warren writing a 5-4 decision, overturned the conviction, because Miranda had not been officially warned of his right to remain silent. The case was retried and Miranda was convicted and imprisoned on the basis of other evidence that included no confession.

An important fact about this case was that Congress soon wrote legislation making the reading of "Miranda Rights" unnecessary, but the Supreme Court then declared in the Dickerson case that Congress had no right to overturn a Constitutional right. Some of the subsequent fury about the Miranda case concerned the legal box it came in, with empowering the Supreme Court to create a new right that is not found in the written Constitution. Worse still, declaring it was not even subject to any other challenge by the other branches of government. In the view of some, this was a judicial power grab in a class with Marbury v Madison.

Several lawyers were at the lunch table on Camac Street, seemingly in agreement that Miranda was a good thing because the core of it was not to forbid unwarned interrogation, but rather a desirable refinement of court procedure to prohibit the introduction of such evidence into a trial. The lawyers pointed out the majority of criminal cases simply skirt this sort of evidence, use other sorts of evidence, and the criminals are routinely sent or not sent to jail without much influence from the Miranda issue. Indeed, Miranda himself was subsequently imprisoned on the basis of evidence which excluded his confession. What's all the fuss about?

And then, the agitated non-lawyers at the lunch table proceeded to display how deeper issues have overtaken this little rule of procedure. This Miranda principle prevents police brutality. Answer: It does not; it only prevents the use of testimony obtained by brutality from being introduced at trial. Secondly, Miranda contains an exception for issues of immediate public safety. Answer: What difference does that make, as long as the authorities refrain from using the confession in court? The chances are good that a person visibly endangering public safety is going to be punished without a confession. Further, the detailed procedures within Miranda encourage fugitives to discard evidence before they are officially arrested in a prescribed way. Answer: If the police officer sees guns or illicit drugs being thrown on the ground, do you think he needs a confession? Well, what about Guantanamo Bay? Answer: What about it? We understand the prisoners are there mainly to obtain information about the conspiracy abroad and to keep them from rejoining it. The alternative would likely be their execution, either by our capturing troops or by vengeful co-conspirators they had incriminated.

Somehow, this cross-fire seemed unsatisfying. The Miranda decision was made by a 5-4 majority, meaning a switch of a single vote would have reversed the outcome. The private discussions of the justices are secret, but it seems likely that some Justices were swayed by this edict viewed as a simple improvement in court procedure rather than a constitutional upheaval; Justices with that viewpoint feel they know the original intent and approve of it. Others are apprehensive the decision has already migrated from the original intent, in an alarming way. Everyone who watches much crime television and even many police officials feels that Miranda intends for all suspects to be tried on the basis of total isolation from interrogation from start to finish. More reasoned observers are alarmed that the process of discrediting all interrogation will lead to an ongoing disregard of the opinion of lawyers about court procedure, essentially the process of allowing public misunderstanding to overturn legal standards. Chief Justice William Renquist, no less, poured gasoline on this anxiety by declaring that Miranda has "become part of our culture".

What seems to be on display is the mechanism by which Constitutional interpretation drifts from the original intent. Not so much a matter of "Judicial Activism" which is "legislating from the bench", it is becoming a matter of non-lawyers confusing and stirring up the crowds until the Justices simply give up the argument. Drift is one thing; virtual bonfires and virtual torch-light parades are quite another.

Originally published: Monday, May 17, 2010; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 29, 2019