Related Topics

Franklin Inn Club

Hidden in a back alley near the theaters, this little club is the center of the City's literary circle. It enjoys outstanding food in surroundings which suggest Samuel Johnson's club in London.

Religious Philadelphia

William Penn wanted a colony with religious freedom. A considerable number, if not the majority, of American religious denominations were founded in this city. The main misconception about religious Philadelphia is that it is Quaker-dominated. But the broader misconception is that it is not Quaker-dominated.

Academia in the Philadelphia Region

Higher education is a source of pride, progress, and aggravation.

Literary Philadelphia

Literary

TOAST TO E. DIGBY BALTZELL (1915-1996)

A TOAST TO E. DIGBY BALTZELL (1915-1996)

The Franklin Inn Club, Philadelphia

Annual Dinner, 15 January 2010

|

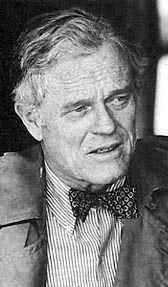

| E. Digby Baltzell |

I am grateful that our President, Deborah Goldstein, and the Board have given me this opportunity to make precedent -- tonight to strengthen the tradition of the Franklin Inn Club by raising a new toast, following our 18th century icon, Benjamin Franklin, and the 19th century men who founded the Inn, with a 20th century member. We are, after all well into the 21st century. It is my original privilege to honor a member and author who contributed strongly to American social thinking: E. Digby Baltzell.

Digby and WASPS Let me right away make two statements about Digby and WASPS. His name is associated with that acronym because it appeared in his book of 1964, THE PROTESTANT ESTABLISHMENT; ARISTOCRACY AND CASTE IN AMERICA. But contrary to a popular misconception, Digby did not invent the term WASP. I know, because a Jewish girlfriend from New York City used that term on me critically ("That's what we call people like you") in 1952. And there is good evidence that the term was in use as a put-down, like other American ethnoreligious slurs, two decades before Digby gave his term for White Anglo-Saxon Protestants scholarly standing in his book.

Secondly: however dear his idea was to him, Baltzell gave up on WASP aristocracy before his death. His subtitle had contained his aim: "Aristocracy and Caste in America." He was inspired by Tocqueville's attempt to save the French aristocracy from its own destruction by writing "Democracy in America" during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Baltzell was concerned about his own aristocratic class. These were prep school and Ivy League educated people with family lineage, trust funds, and above all, what might be called Rooseveltian motivation. Either TR, Republican, or FDR, Democrat, party did not matter. Both Roosevelts had the aristocratic drive to excel: not only to lead but to assimilate other talents into leadership. That was the key to the matter: for a responsible aristocracy perpetuates itself by absorbing into ruling power new immigrant energy and multi-class talents, such as, in the 1930s, Fiorello LaGuardia, mayor of New York City, and Sidney Weinberg of Goldman Sachs.

An aristocracy is irresponsible, however, when it merely replicates its own ethnic and religious features. By protecting itself with clubbishness it ceases to be an aristocracy and rigidifies into a caste. Baltzell, 1964, feared that WASPS in the USA would let that happen, and wrote in the strong hope that they would not. But it was already happening. Looking back, we can see that the game was almost over.

Digby and Me Who was Digby Baltzell? He was born in Rittenhouse Square and grew up in Chestnut Hill to what he called an "impecuniously genteel" family. They sent him off to St. Paul's School in New Hampshire, an exclusive Episcopalian* boarding school formed in an English tradition. In his senior year, his alcoholic father was fired from his insurance company, and soon after died of a heart attack. For college, Digby could not afford Harvard, Yale, or Princeton, where all his classmates went but settled for the University of Pennsylvania. There he got himself through on scholarship, with various jobs such as ticket-taker, usher, and parking lot attendant at Franklin Field. He went on to get a Ph.D. at Columbia and came back to Penn, where he taught for the rest of his employed career.

I never met Digby personally because he died in 1996, the year that I joined the Inn. Yet I identify with the man I just described in some distinct ways. My own alcoholic father, a mellow, dear, and vulnerable man, lost his job as a stockbroker while I was in college. There, at Williams, I was a member of the same hard-drinking fraternity, St. Anthony Hall, as Baltzell had been at Penn. I'm not Episcopalian, but being a Scotch-Irish Presbyterian makes me categorically WASP. I feel like Digby did, that I have been a marginal member of the elite. I became an academic to try to figure out what the hell was going on around me. I have, like him, "an insider's heart and an outsider's mind." That has qualified me not to make a fortune, but to write books.

Digby and Us We all live in a time of social phenomena Digby never reckoned with -- of Bill Clinton as a white trash national leader; of John Kerry, a Catholic agnostic from St. Paul's School who lost the election of 2004 to G.W. Bush, a retrograde pseudo-Texan who had renounced his father's waspismo. Personalities that Baltzell might barely have imagined: Oprah Winfrey, a multicultural pop icon who is incidentally black; and the Afro-Saxon lawyer-intellectual whom we have chosen President of the United States, Barack Obama.

Baltzell finally gave up the attempt to invigorate his idea of a responsible ethnoreligious elite. He realized, and said, "what the Jews have done since World War II is the great untold story." And when he died he was preparing to undertake a book on the end of the Protestant establishment. He recognized that it had been replaced by a meritocracy based on professional performance, which, I think, is far more congruent to American social dynamics. I conclude that Baltzell's last and never completed project was an admission that his three books on the WASP establishment were a failed effort to firm up a transient power structure. I believe that Baltzell had been trying to implant in America a British notion of ruling class flavored with Tocquevillean nostalgia for a lost French aristocracy. Our nation has wholly different components from those, and he was bound to fail. Even as he struggled to make the point, he acknowledged the multi-cultural society around him, while expressing a vivid fear that multi-culturalism enshrined meant moral relativism, which would, in turn, mean an unworkable political system. On that last, he may yet prove correct. And he was surely astute in recognizing the importance in America of a professional meritocracy. If any of us, nonetheless, still yearns for an aristocracy of some kind, I would recommend Jefferson's idea of "a natural aristocracy based on talent and virtue."

Digby, although a connoisseur of clubs noted in the Social Register, never joined one, although often invited to do so. He criticized, among others, the Duquesne Club in Pittsburgh, the Links Club in New York, and the Philadelphia Club here for their obtuse and pointless exclusiveness.** But he chose to be a member of The Franklin Inn Club, and in his later years often came from home on Delancey Street to lunch among members. Our cultural, artistic, and literary atmosphere, we may dare feel, was comfortable for him. What he found here was perhaps an aristocracy without power, but a natural one in its components of talent and virtue. Sisters and brothers: let us toast Digby Baltzell -- an exemplar of our values, and an inspiration to us in the Twenty-First Century.

Theodore Friend

|

| Theodore Friend Sr. |

*To the rumor that Baltzell became a Roman Catholic before he died, a close living relative says no: he very much respected the Catholic Church, was interested in healing the breach with Episcopalians and may have attended some Catholic services. But nothing more.

**A Jewish friend, responding to my inquiries, tells me that he was admitted to The Union League in 1967, and about twenty years later became chair of the Admissions Committee. What percentage of members now are Jewish? He estimates five percent.

Sources:

Baltzell, THE PROTESTANT ESTABLISHMENT: ARISTOCRACY AND CASTE IN AMERICA , (1964)

PURITAN BOSTON AND QUAKER PHILADELPHIA, (1979)

THE PROTESTANT ESTABLISHMENT REVISITED, (1991)

Brief conversations with members of the Franklin Inn:

Daniel Hoffman, Nathan Sivin, and Arthur Solmssen.

Originally published: Friday, January 29, 2010; most-recently modified: Thursday, June 06, 2019

| Posted by: Michael Rowe | May 16, 2011 10:39 AM |