Related Topics

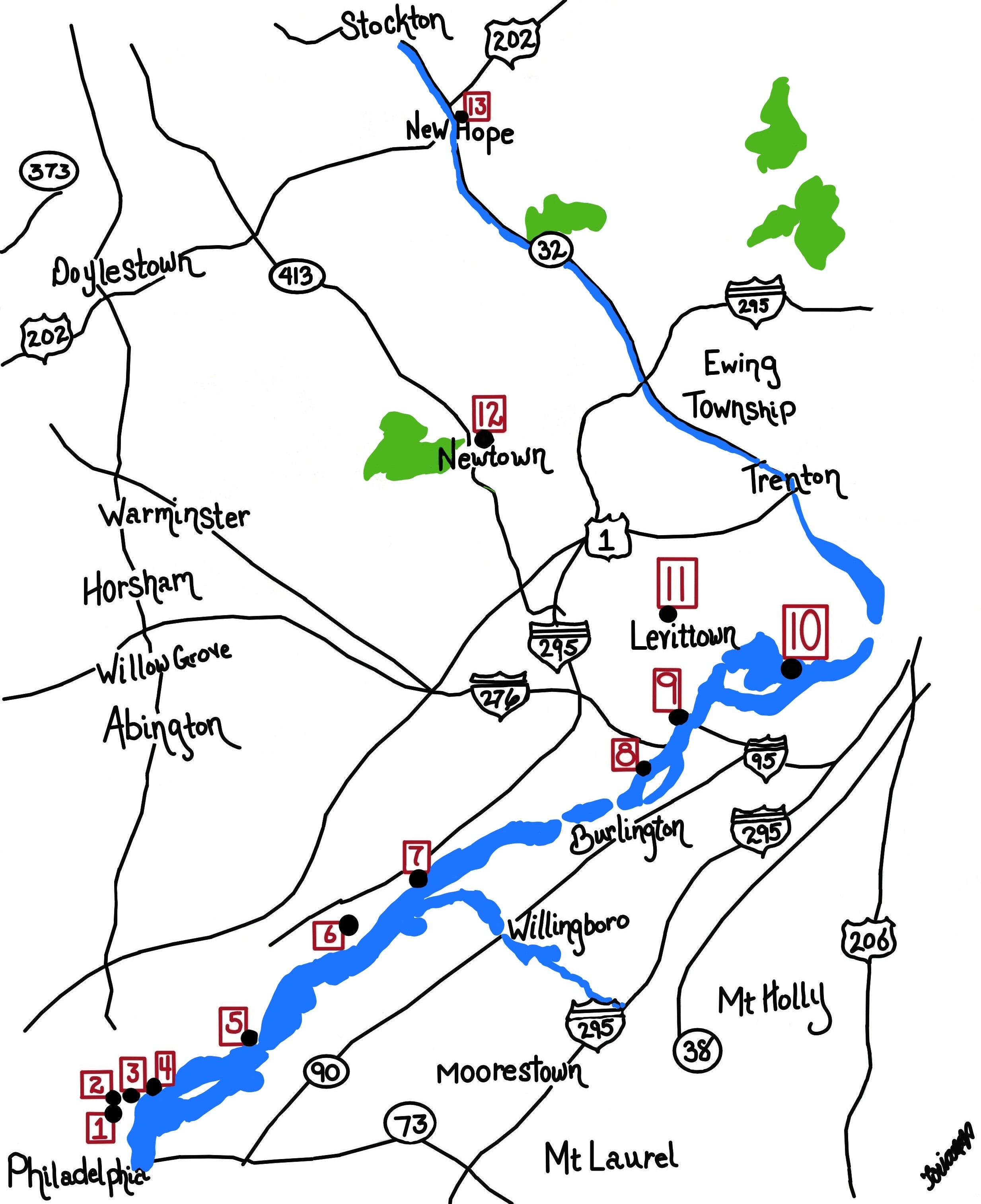

Philadelphia's River Region

A concentration of articles around the rivers and wetland in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Park and Beyond: East Falls, Germantown, Mt. Airy and Chestnut Hill

Fairmount Park is large enough to split the City from its suburbs, and is partly a playground, partly a museum. East Falls, Germantown and Chestnut Hill are almost a separate world on the far side of the park.

Philadelphia Fish and Fishing

Less than a century ago, Delaware Bay, Delaware River, Schuylkill River, Pennypack Creek, Wissahickon Creek, and dozens of other creeks in this swampy region were teeming with edible fish, oysters and crabs. They may be coming back, cautiously.

Historical Preservation

The 20% federal tax credit for historic preservation is said to have been the special pet of Senator Lugar of Indiana. Much of the recent transformation of Philadelphia's downtown is attributed to this incentive.

City of Rivers and Rivulets

Philadelphia has always been defined by the waters that surround it.

Food and Drink in Philadelphia

A flowing abundance of food sources made Philadelphia the capital of food and drink, right from earliest times.

Nature Preservation

Nature preservation and nature destruction are different parts of an eternal process.

Architecture in Philadelphia

Originating in a limitless forest, wooden structures became a "Red City" of brick after a few fires. Then a succession of gifted architects shaped the city as Greek Revival, then French. Modern architecture now responds as much to population sociology as artistic genius. Take a look at the current "green building" movement.

Right Angle Club 2009

The 2009 proceedings of the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia, beginning with the farewell address of the outgoing president, John W. Nixon, and sadly concluding with memorials to two departed members, Fred Etherington and Harry Bishop.

Water Works, Emblem of the Past

|

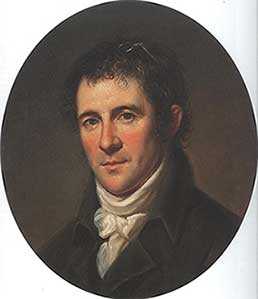

| Benjamin Henry Latrobe |

Philadelphia didn't really want the national capital to move to Washington DC, but the yellow fever epidemics, brought from Haiti by refugees, made it politically impossible to reverse the decision to move. We now know that Yellow Fever is transmitted by mosquitoes, but there were enough trash and pollution lying about the that it was plausible that polluted water was the cause. With no time to waste, water was piped in, through wooden pipes, from the comparatively pristine Schuylkill to a pumping station in Center Square, where City Hall now stands. Even today, no one wants a water tower in the neighborhood, so Benjamin Henry Latrobe made it look like a Roman Temple, thereby introducing classical architecture to Philadelphia, and starting quite a trend. The new system worked well enough from 1801 to 1815, when the new city outgrew it. Therefore, a new pumping system was built at the base of Faire Mount, where William Penn once planned to have a mansion, and was attached to Latrobe's wooden pipe system. In a unique and ingenious way,

|

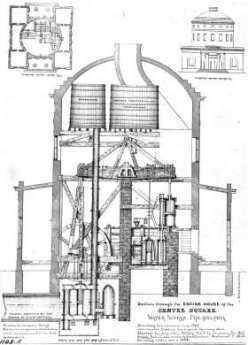

| Latrobe Water Works |

Frederic Graff pumped Schuylkill water up to a series of reservoirs on top of Faire Mount, utilizing a water stack to maintain constant pressure. The classical architecture was continued, parks and decorative gardens were placed around it, and admirers came from around the world to marvel. Meanwhile, Latrobe's original building could now be torn down, providing room for City Hall, which was planned to be the tallest building in the world, although the French sort of cheated and put up Eiffel Tower, which in a sense really isn't a building. Meanwhile, Philadelphia and the rest of America kept growing and growing, leading to industrial plants along the Schuylkill all the way up to Pottsville, where the anthracite came from. The pure sparkling municipal water of which Philadelphia was so proud soon became a stinking sewer, and the Civil War encampments accelerated the process.

|

| Frederic Graff |

Following the lead of the Philadelphia College of Physicians, the concept of Fairmount Park emerged from clearing the banks of the river, and the Wissahickon Creek, of industry. The Philadelphia Water Works thus became the southern anchor of the largest city park in the world, including the building of Laurel Hill Cemetery, which had sanitary overtones which were embarrassing to discuss. Philadelphia led the world in adapting to this particular feature of the Industrial Revolution, and the insights of Louis Pasteur. By 1890, however, the system was again outmoded, and Philadelphia water became the butt of every joke. Between 1815 and 1840 the wooden pipes were replaced by iron ones. Robert Morris's old estate of Lemon Hill was acquired by Fairmount Park and used to construct a second reservoir on the neighboring hill. More about that second reservoir, in another blog.

Eventually, there would be more reservoirs at Belmont and Green Lane. But the city's new reputation for foul water was deserved. Deaths from typhoid fever rose to 80 per 100,000 residents before a water filtration system was installed; deaths from typhoid promptly fell to 2 per 100,000. Statistics on hepatitis were not available, but virus diseases must have been a serious hazard under primitive conditions of filtration, aeration and chlorination -- as they still are in many third-world countries, and in most southern European nations before 1950. As late as 1950 in Philadelphia, it was considered witty for a dowager to accept a drink from her hostess, saying "I'll drink absolutely anything, except Philadelphia water -- and 'Coke' ". The implication was that alcohol sterilizes water, which of course it doesn't, and also that absolutely everybody knows that Philadelphia has terrible water, whatever that means.

A reputation like that is bad for the city, making it harder to persuade workers and business to locate here, but the traditions underlying this response are quite ancient. Back in the days when water came from your own well, whole neighborhoods would move to new unspoiled areas to seek cleaner water and regions where the local privies were not yet mature. It takes quite a lot to persuade people to abandon the investment in a home or mansion as in Society Hill, and build a new one in a nearby undeveloped region. Particularly when the germ theory was not yet available to explain the issues with precision, pulling up stakes for a new neighborhood was an accepted reaction to almost any threat.

|

| Water Works Today |

However, strenuous exertions for half a century have made Philadelphia water safer, tastier, and far cheaper than bottled water. The recent trend of young people to walk about sucking a three dollar bottle of water drives the Philadelphia Water Department up to a wall. For example, 25% of bottled water comes straight from the tap. The inspection standards for public water are much stricter than for commercially bottled water, whose safety is in large part secondary to the safety of the tap water from which it is derived. True, public water is chlorinated, but then it is also fluoridated, putting legions of dentists out of business. In Philadelphia, that's the main difference justifying the rather appalling price difference, and the accumulation of plastic bottles in various trash heaps.

The recent advances in Philadelphia's water can in part be traced to Ruth Patrick, now over a hundred years old but the world's foremost expert on streams and water, and to the persistent professionalism of the Philadelphia Water Department. Perhaps, though, it may take a century of slander about water to persuade the politicians to keep their hands off the Water Department. It does take a lot of tax money to implement the third step in the process of cleaning up the water supply, which is the purification of wastewater. For centuries, the guiding principle was to obtain and maintain pure water at the source; wastewater was flushed down the sewer to go back out to the ocean. However, seven times as much water is removed from Delaware, as it flows past the city. That is, the water now recirculates through the sewage system seven times before it is turned over to residents of lower Delaware Bay. The expensive and elaborate -- but scarcely visible -- system of treating sewage in various sewage treatment centers has now resulted in returning water to Delaware in better condition of purity than it had when it came down past Bucks County.

But it costs lots of bucks, and nobody seems to notice the water. People only notice the bucks.

Originally published: Friday, September 11, 2009; most-recently modified: Friday, May 31, 2019