Related Topics

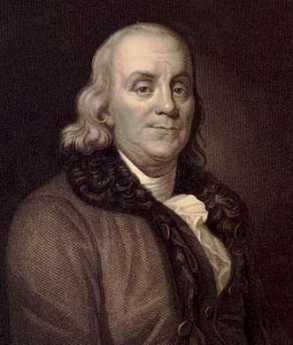

Benjamin Franklin

A collection of Benjamin Franklin tidbits that relate Philadelphia's revolutionary prelate to his moving around the city, the colonies, and the world.

Franklin on British American Relationships

|

| Edmond S. Morgan |

Edmond S. Morgan spent an academic lifetime collecting and organizing the many volumes of what Benjamin Franklin wrote, and what he has been quoted as saying. Professor Morgan knows more than anyone else will ever know about what Franklin wrote down and signed his name to. Obviously, these records of a long and remarkable career are filled with instances of some of the very wisest, most penetrating observations about earth-shaking events. Although his writings are almost always charming and witty, succinct and penetrating, some of his proposals and comments about important matters could, however, be contradictory and sometimes half-baked. It's sometimes hard to admit that.

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

It's difficult to make entire sense of his attitude toward royalty, for example. For years during the time he represented the colonies at the Court, it would seem his vision of the future was that of multiple parliaments, held together by a common loyalty to the King. The concept is somewhat akin to the devolution movement now rumbling around the United Kingdom. It's hard to reconcile that proposal with some of the activities of George III that Franklin was in a position to watch, and it seems a little dubious for him to believe the major errors of the British government were to be mainly blamed on a handful of evil ministers misguiding the monarch. And harder still to reconcile this loyalty to the throne with his indifference or resistance to the American republic having a strong presidency at the later Constitutional Convention -- when his opinion might have made a major difference if it had been sensible. Some of these ideas may be remnants of poorly digested attitudes about the earlier English Civil War or reactions to the behavior of Cromwell. Franklin spent years watching the British Parliament in action and much time lobbying its members in proposed deals and arrangements. It's easy to see how he might have been disillusioned at times, but it's very hard to see the sense of his conclusion that the Parliament was an impediment to ideal relations between the sainted King and his obedient subjects. Since Franklin was not writing rebuttals to himself for saying contradictory things several years earlier, it is very hard to know what he really thought when you bring all these writings together; and unwise to be too certain what it tells us about Franklin.

|

| British Ministries Symbol |

There is one thread which weaves for many decades among Franklin's writings, probably coming close to reflecting a hardened, considered, position. As a young man, he could easily observe the American population and wealth growing much faster than growth in the mother country, projecting forward to the firm belief that America would in time eclipse England. Today we see this as common sense, but in the Eighteenth-century population growth was believed to be secondary to economic growth. Some of the seemingly selfish and detestable mercantile policies of the British ministries were based on a sincere belief in this incorrect view of population. Since Franklin saw it was wrong, it is regrettable that he failed to take the approach of discrediting the theory rather than assailing those who mistakenly believed in it.

Taken all together, his 1767 letter to Lord Kames seems to represent Franklin's core position. Closer political union based on equality would actually benefit Britain more than it would America by preserving for Britain an equal place in an empire that must soon be principally American. America had resources far outweighing what British Isles possessed. It was bound to "become a great country, populous and mighty; and will in less time than is generally conceived be able to shake off any Shackles that may be imposed on her, and perhaps place them on the Imposers. In the mean Time, every act of Oppression will sour their Tempers... and hasten their final Revolt."

We now see that as very perceptive, although events diverted matters in other directions for two centuries before returning to the essential truth. The Industrial Revolution was England's achievement before it became the world's. And the Industrial Revolution, not the American one, was central to the British conquests which positioned the Empire for far greater growth than Franklin could foretell. He thought America would overtake England in less than a century, but in fact, it took two centuries. This is one of those arguments where both sides are proven right, but at different times.

|

| Benjamin Franklin Discovers Electricity |

But while some other false starts about governmental design can perhaps be defended by signed correspondence at the time, they leave behind the embarrassing opinion that it was a good thing he occasionally got distracted by electricity experiments and flirtations with lady friends. And thus, sustained defeat of his silly 1752 proposal to displace the Pennsylvania Proprietorship with a Royal colony, and the equally ill-judged 1787 scheme to replace the American presidency with a debating club. Franklin was a statesman without equal, but no unedited lifetime correspondence can withstand scrutiny as a coherent political theory.

Originally published: Thursday, June 25, 2009; most-recently modified: Friday, September 20, 2019