Related Topics

...Ratification, Bill of Rights and Other Amendments

The 1787 Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights. Few except Madison himself were opposed to adding one, but many other delegates would have failed election without promising it. Negotiations at the Convention had proved so excitingly innovative that time ran out before the Convention had to adjourn with only a promise of a Bill of Rights, first thing.

Philadelphia Legal Scene

The American legal profession grew up in this town, creating institutions and traditions that set the style for everyone else. Boston, New York and Washington have lots of influential lawyers, but Philadelphia shapes the legal profession.

Federalism Slowly Conquers the States

Thirteen sovereign colonies voluntarily combined their power for the common good. But for two hundred years, the new federal government kept taking more power for itself.

...Pending and Later Amendments

New topic 2012-08-01 19:06:55 description

Eleventh Amendment

There are certainly a lot of Ingersolls in Philadelphia. A lot of Jared Ingersolls, a lot of Charles Ingersolls, and even a lot of Charles Jared Ingersolls. At a dinner party, a lady whose maiden name is Ingersoll was asked about Charles Ingersoll, and was forced to say, "Just how old would you say he is?"

|

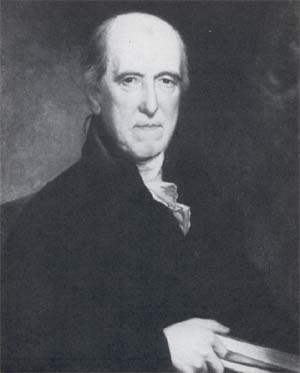

| Jared Ingersoll, Jr., |

The one we are talking about here is Jared Ingersoll, Jr., the son of a Tory who had once been tarred and feathered by Revolutionaries in New Haven. Young Jared was in England at the Inns of Court when the Declaration was signed, became a fervent Revolutionary, and represented Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention. It was thus difficult to predict where his sympathies would lie in the settling of debts and grievances associated with the Revolutionary War; in fact, he might be as impartial as any lawyer to be found at the time. At their best, all lawyers reach for the peaceful settlement of grievances, serving their clients best by finding a solution that puts an end to reprisals. Furthermore, he had excellent legal training, something which could not be said of most apprentice-trained lawyers of that time, and had faithfully attended every single session of the Continental Congress, while commenting very little about his own views. The first ten amendments are the Bill of Rights which had been promised during the ratification process, so the Eleventh became the first real amendment, in the sense that it specifically reverses some feature of the original design. To present observers it may not be easy to surmise just what the purpose might have been to outlaw the method which had been established for an injured citizen to sue a state. To be blunt about this point, the colonists wanted to welch on paying debts to Loyalists and Englishmen, those hated enemies, without admitting this was their motive. The spin they put on this shabby attitude was that states were now sovereign entities without a king, and since historically a British king could not be sued without his consent, therefore neither could the states. Probably the best that can be said for this cloud of words is the point that suing the government should not be made too easy, for fear of overwhelming the court system with endless clamor. The historical episode surrounding the Eleventh Amendment is an important one in our national struggle to balance the accusations of hypocrisy and chiseling, with the opposite tendency of slavish adherence to procedure, or "due process".

|

| Alexander Chisholm |

Ingersoll had attended the Constitutional Convention as part of the most influential state delegation of insiders and was set up to practice law in the capital city of Philadelphia just a few blocks from the heart of government. A case came up. The estate of Captain Robert Farquhar, an Englishman, was owed $169,613.33 for "goods" sold in 1777 to agents of the embattled State of Georgia during the Revolution. The executor of Farquhar's estate, a resident of South Carolina named Alexander Chisholm, then sued the state of Georgia after the war was over for that state's extinguishing the debt by a statute passed after the contract. This had been the rather common treatment of Loyalist debts by other colonies and thus enlisted their sympathies to Georgia in this case. Furthermore, it was the sort of uncivil behavior that had enraged John Jay and George Washington, leading them to press for the Constitutional Convention. On the other hand, the new state governments were hard-pressed for cash and had to contend with highly combative citizens who resented even the suggestion that they play fair with people who had so recently been trying to kill them. Furthermore, it was entirely realistic for them to fear a flood of lawsuits from people they mercilessly pursued under what "everyone" considered the rebellion's accepted rules of engagement. It was thus clever for Georgia to seek the help of Ingersoll in appealing to the Supreme Court, and the previous tarring and feathering of his Loyalist father was not entirely irrelevant. Ingersoll, unfortunately, lost his case of Chisholm v Georgia when the Supreme Court (John Jay, CJ) declared that Chisholm was indeed entitled to sue the State of Georgia. It is hard to see how Ingersoll (and his colleague Alexander Dallas) could have won this case when the Constitution which he helped write plainly provided the rules for citizens of one state suing another state; it seems remotely possible that the officials of Georgia were attempting to shift the blame of an inevitable loss of the suit:

Article III - Section 2 -The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

John Jay ultimately revealed the depth of his dismay at dishonoring debts when he negotiated Jay's Treaty during the Adams administration, providing for adjustment of such debts. Adams, in turn, was to reveal where his own sympathies lay by refusing to announce -- for three years -- the reversal of this position by the Eleventh Amendment, stirred up in his own state. Adams' rather flagrant abuse of a technicality might well have led to another constitutional amendment, except for the Supreme Court later ruling that official enactment of amendments did not require Presidential announcement, but took effect upon ratification by the required number of states.

Adams, in turn, had ample political problems in his home state of Massachusetts. John Hancock, then Governor, called a special session of the Massachusetts legislature to propose an amendment to reverse the Constitutional language on which the Supreme Court's decision had relied: It soon became clear, or perhaps Ingersoll was determined to make it seem clear, that Georgia had been smart to employ this political insider. Congress soon enacted, and the necessary states soon ratified the Eleventh Amendment. It stated that a citizen of another state may not sue a State government in Federal Court:

Amendment XI. The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.

Later decisions included citizens of the same state, so in effect, this amendment stated that no one may sue a State Government unless the state agrees to be sued. That's essentially what is true of the federal government; the states were given the same sovereignty with all of its features, as the federal government and that was an intentional slap in the Federalist faces.

It sounds as though Jared Ingersoll might have been a states-righter, although nothing in his past or future behavior suggests that he was anything but an ardent Federalist. He was even proposed as vice presidential candidate for the Federalist Party. No one called him wishy-washy, or a traitor or a covert anti-federalist, and he never acted like one. He was just a lawyer with a client.

Originally published: Tuesday, June 16, 2009; most-recently modified: Saturday, September 07, 2019