Related Topics

Historical Preservation

The 20% federal tax credit for historic preservation is said to have been the special pet of Senator Lugar of Indiana. Much of the recent transformation of Philadelphia's downtown is attributed to this incentive.

Customs, Culture and Traditions

Abundant seafood made it easy to settle here. Agriculture takes longer.

Academia in the Philadelphia Region

Higher education is a source of pride, progress, and aggravation.

Volunteerism

The characteristic American behavior called volunteerism got its start with Benjamin Franklin's Junto, and has been a source of comment by foreign visitors ever since. It's still a very active force.

Wagner Free Institute of Science

|

| Wagner Institute Logo |

William Wagner emigrated to Philadelphia as a prosperous merchant shortly after the nation was formed, becoming a friend affiliated in business with Stephen Girard, although never a partner. Business took him around the world, where he pursued his hobby of collecting scientific specimens. The collection grew until it needed a museum to house it, accordingly built on the family farm somewhat north of the city limits, now 1700 Montgomery Street. A woodprint shows a game of baseball in play in the fields, with the museum recognizably looming in the background. Those fields are now filled with Nineteenth century red brick Philadelphia rowhouses, built later to support the activities of the Museum. Unfortunately, a need for a parking lot was not anticipated in 1848, but the place is quite safe to visit because land directly across 17th Street, also part of the original Wagner farm, was given over to the 22nd District police station. It's even possible the parking issue has since been considered since nearby land was deeded to a Unitarian Church on condition of reverting to the museum if it stops being a church.

|

| William Wagner |

William Wagner became the first director of his museum, following the ideas of his friend Girard a few blocks to the south. Stephen Girard had left his estate to the education of poor white orphan boys; Wagner extended the idea of offering free scientific education to the working public. The example ofBenjamin Franklin's discovery of the nature of electricity with only a second-grade education is a locally dramatic example of the important truth that science can be enjoyed and even skillfully performed without academic preparation or advanced degrees. Science in the early Nineteenth century evolved from Natural Philosophy to what we now call Natural Science, heavily weighted toward geology, botany and zoology with a strong dose of Charles Darwin. Today, those ideas are having a reawakening in the Green (Environmental) Movement, so perhaps a resurgence of interest really is about to appear. The museum might be called a historical record of Nineteenth-century science, although its lecture series are wider ranging and, of course, up to date. Reflecting the intended science education of the working public, many of the lectures are given in the evening and on weekends. Many are given in other locations, like the Free Library branches. The Wagner resembles the Barnes Museum in the sense that two museums once intended to illustrate educational innovations have come to overshadow the public's perception of the educational programs, whereas the cost of maintaining museums grew far faster than the income from endowments. It all resembles academia in general in getting progressively more expensive to provide for.

|

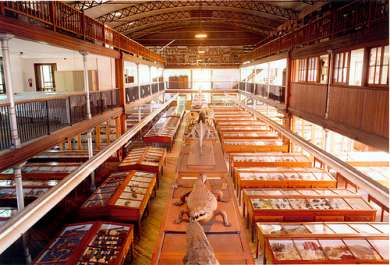

| The Wagner Museum |

The Wagner museum was formally opened in 1854, about the time of the City-County consolidation which relieved the population pressure needing to fill up surrounding fields with redbrick rowhouses, and eventually with Temple University. The formal Institute directorship was transferred to the professional management of Joseph P. Leidy, a dynamo of a man who received the informal title of The Last Man Who Knew Everything. When Leidy retired at the end of the Nineteenth century, the museum was closed to further acquisitions. For those who can remember natural science museums around 1930, the Wagner is strongly reminiscent, but over time it has become one of the few, perhaps the only, surviving example of the type. The building next door is a scientific library, available to scholars by appointment. The Athenaeum and the Mutter Museum are also surviving museum monuments, but even those two have been elaborately modernized. The Wagner resolutely adheres to looking as much like the original as maintenance will permit. The structure is as interesting as the contents; only the lecture topics move forward with the times.

|

| Anna Karenina |

The Institute drifted away from the Wagner family, but a few Wagners of the present generation became attracted by the connection to their name, and have struggled to keep it alive. The board has a few Wagner family members, who do their best to spark the enthusiasm of others who value the lectures, the scientific educational movement, and historical quality of an expensive but unique museum in a difficult neighborhood. Quite a few loyalists throng around the evening lectures with a happy air of joint participation and tradition. It would be hard to overlook the sincerity and courtesy that hovers around the edges of a shared cultural belief. It's a family activity, all right, but it is no longer a Wagner family but a Wagner Museum family. Participants are unmistakeably really happy that visitors have come to see it. The opening lines of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina declare that all happy families are happy in the same way, but that's wrong. The Wagner Museum family are obviously happy but in a unique way. In a nation which so universally prizes the future, here's one group who have seen the merit of having some institutions grow in value by seeming to stay just the way they began.

Originally published: Wednesday, March 04, 2009; most-recently modified: Friday, May 31, 2019

| Posted by: Bob Irving | Dec 7, 2014 3:23 AM |