Related Topics

Philadelphia Politics

Originally, politics had to do with the Proprietors, then the immigrants, then the King of England, then the establishment of the nation. Philadelphia first perfected the big-city political machine, which centers on bulk payments from utilities to the boss politician rather than small graft payments to individual office holders. More efficient that way.

Customs, Culture and Traditions

Abundant seafood made it easy to settle here. Agriculture takes longer.

Philadelphia Economics

economics

Montgomery and Bucks Counties

The Philadelphia metropolitan region has five Pennsylvania counties, four New Jersey counties, one northern county in the state of Delaware. Here are the four Pennsylvania suburban ones.

Merging Cities With Their Suburbs

|

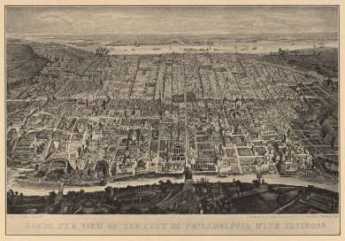

| Philadelphia 1854 |

When the City of Philadelphia turned into the County of Philadelphia (or vice versa) in 1854, the area had about 150,000 residents in 1850 but 500,000 in 1860. It qualified as one of the largest cities in America at the time, but what we today call middle-sized cities are about that same size. As a generalization, when a thriving American city approaches a size of about half a million, the business community often gets the idea that the city should expand its limits by annexing the neighboring districts. And, as a further generalization, the metropolitan newspapers are simply ecstatic about the idea of expanding their market reach, while the working classes of both the city and the region it proposes to swallow, are violently opposed. Since the business community typically feels that expansion would be good for business, labor unions are subdued. Leadership of the conservative middle-class rebellion is therefore generally led by the police and volunteer firemen, who are the most organized groups within the combative working class in a metropolitan region. Many citizens of all classes are of course quite indifferent about the matter. As history has turned out, only one such proposal in five will be successfully adopted, but it is almost unheard-of for a successful amalgamation to be reversed once it happens. In recent years, this general pattern has been followed in Indianapolis, Lexington, Jacksonville, Nashville, Baton Rouge, and Louisville. In countless other cities, the effort has been defeated by the voters.

It requires thriving prosperity for the business community to become politically dominant in a city, so the political context of these circuses amounts to a contest between the business "elite", often augmented by "carpet baggers from out of town" threatening comfortable lives within settled neighborhoods by merging them with culturally discordant residents in suburbs or countryside. On a political level, professional urban politicians favor expansion, because increasing the electorate generally makes it more expensive for an outsider to raise the funds to defeat them in an election. Exceptions to this rule occur when the two merging regions have different political parties in control, or when working-class city districts are so opposed that urban politicians fear to anger them. A symptom of this conflict for control of a city machine can be observed in the seemingly unrelated issue of a city charter with a "strong mayor" design. Cities with a strong city council generate greater ability to defeat the machine and are hence more reluctant to see mergers with suburbs. Nevertheless, the attraction which the business community can offer to the politicians is a larger tax base, although in the surrounding suburbs the dynamic is exactly the opposite. In the suburbs, it is the local businesses and professions who feel threatened, and who attempt to agitate the suburban politicians to protect their tax collections.

Although campaign rhetoric in these battles tends to exaggerate or distort the probable economic changes, academic studies find that the actual effect of city expansion is generally of modest subsequent growth, with modest increases in taxes. These effects seem comparatively weak since a metropolitan region is unlikely to produce a successful merger unless the economy is already growing fast enough to generate expansionism, and that vigor is likely to persist after the merger. These political uproars talk a great deal about economics, but in fact, the issue is primarily political. One commentator calls them "chess games pretending to be circuses", and the real force at work is usually an elaborate variation of gerrymandering. Urban minorities who usually vote Democrat can be swallowed up by suburban majorities who usually vote Republican. Or else a thwarted inner-city business community hopes to replace the urban machine with a more favorable suburban set of attitudes. There is seldom a uniform political gradient as the city border is approached from either side, so the chess game takes these patchwork population variants into detailed consideration. It is often argued that crossing a political boundary is unworkable, but since the thriving city of Atlanta is located in two different counties, that must not be a dispositive argument.

In their most elemental form, these expansion efforts have to do with political boundaries. It is therefore not surprising that the people most concerned are politicians. The battle cry is often to create a city without suburbs; failure to act leads to suburbs without a city. In fact, the underlying agendas are much more prosaic.

Originally published: Thursday, January 22, 2009; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 23, 2019