Related Topics

Philadelphia Medicine

The first hospital, the first medical school, the first medical society, and abundant Civil War casualties, all combined to establish the most important medical center in the country. It's still the second largest industry in the city.

Philadelphia Physicians

Philadelphia dominated the medical profession so long that it's hard to distinguish between local traditions and national ones. The distinctive feature is that in Philadelphia you must be a real doctor before you become a mere specialist.

Art in Philadelphia

The history of art, particularly painting and sculpture, has been a long and distinguished one. If you add in the art schools, the Philadelphia national influence on artists has been a dominant one.

Historical Preservation

The 20% federal tax credit for historic preservation is said to have been the special pet of Senator Lugar of Indiana. Much of the recent transformation of Philadelphia's downtown is attributed to this incentive.

Tourist Walk in Olde Philadelphia

Colonial Philadelphia can be seen in a hard day's walk, if you stick to the center of town.

Favorite Reflections

In no particular order, here are the author's own favorites.

In no particular order, here are the author's own favorites.

Sixth and Walnut over to Broad and Sansom

In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area still remains dominated by medical institutions.

In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area still remains dominated by medical institutions.

Cultural

Culture and Traditions (2)

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

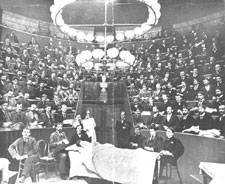

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Originally published: Wednesday, December 27, 2006; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 16, 2019