Related Topics

Philadelphia Legal Scene

The American legal profession grew up in this town, creating institutions and traditions that set the style for everyone else. Boston, New York and Washington have lots of influential lawyers, but Philadelphia shapes the legal profession.

Economic Power of Laws

|

| William Penn |

Philadelphia is tucked down in the Southeast corner of Pennsylvania, right next to Delaware and New Jersey. All three states once belonged to William Penn and started out Quaker-dominated. In time, they settled down to a life of independent states, and with the growth of population plus speed of transportation, they are all getting smudged together again. The Quaker influence is there if you look for it, and rather fierce, even hostile, political competition between the states is there, too. But if you were a foreign visitor who doesn't look at maps, you could drive around the metropolitan area without knowing which state you were in. To a large extent, the Rand-McNally lines are a hindrance to commerce and convenience, but they have their value. The quirks of political jurisdiction give the Philadelphia metropolitan area six U.S. senators, and the opportunity to take shrewd advantage of the three legal systems. You can buy things without a sales tax in Delaware, and estate tax lawyers tell me that if you must die, die in Delaware. At one time, New Jersey was a great place to get an uncontested divorce, Pennsylvania a better place to start an unincorporated business. More recently, the New Jersey doctors are complaining that malpractice rates are unbearable, but they are not as bad as they are in Pennsylvania, and it is rapidly becoming true that if you are going to be born, you will need to be born in New Jersey because the obstetricians have all moved there. That's also true in the District of Columbia; obstetrics has just about entirely fled to Virginia. Better watch out where you have your auto accidents, too. Neurosurgeons and orthopedists have also responded to the local disincentives to living near certain types of juries.

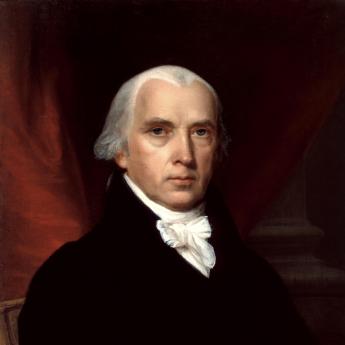

|

| James Madison |

Long ago, James Madison designed things this way on purpose. The main author of our constitution hated taxes and oppressive government as much as any other founding father and argued it was a good thing to let neighboring states have differing laws. Corporations which do interstate business hate the complexity of course, but as Madison argued, people do shift their business, their businesses, and even their residence if the neighboring states become too extreme in their differences. It's still worth a thirty-minute drive to buy silverware and China in Delaware, and if you are driving to the New Jersey shore, you ought to fill up your gas tank on the Jersey side of the bridge. At one time, there was a thriving resort town in the Jersey woods, mostly entertaining people who needed a spell of New Jersey residence to be eligible for New Jersey divorces.

|

| Governor du Pont |

These things respond to local circumstances fairly rapidly. I once met a man from the Delaware Chamber of Commerce who boasted that the Chamber could get a Delaware law changed over a weekend if it had some particular commercial advantage. Governor du Pont saw the bigger advantages of this flexibility and got some laws enacted which drew most of the big credit card companies to Delaware, and at least a branch of all the big national banks. Delaware is starting to emulate Lichtenstein , and fairly successfully.

The effect on Philadelphia banking has been disastrous. Once the banking center of the whole continent, Philadelphia now does not have the headquarters of a single major bank. True, banking is becoming an obsolete industry whose products no one really wants, but the particularly severe effect in Philadelphia comes from the fact that if you were going to have a big bank in the metropolitan area, you would have it in Delaware.

|

| Delaware Court of Chancery |

The location of so many corporate headquarters in the little state attracts lots of outside lawyers, of course, and it puts a heavy burden on the Delaware Court of Chancery, the court for corporate disputes. The judges are appointed by the governor, and it doesn't take all that much outside money to lean on the governor, so the nation's giant corporations are at the mercy of a very small group of local politicians. The politicians, on the other hand, operate freely in an environment where comparatively few of their constituents have any interest in the goings-on of major corporations from far away.

|

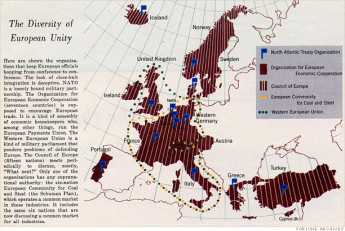

| European Common Market |

It's an interesting thing that the legislatures of all three formerly Quaker states are torn with sectional disputes. In Pennsylvania and Delaware, it's the cities against the farmers. In New Jersey, it's the North versus the South. All states are having a hard time balancing their budgets in a recession, but somehow New Jersey has worse deficits than the others, and therefore more quarrels about taxes. The northern politicians dominate the legislature, and the south feels it is often the victim of state laws designed to help the North in its constant war with New York City. Ever since 9/11, the financial district of New York has been sending its subsidiary employees to safer cheaper regions. That might have meant going to New Jersey, but the tax flounderings there have led to many of those relocations going on a few miles to upstate Pennsylvania. You don't ordinarily think of Scranton as a financial center, but take another look. Madison, no doubt, would smile at the tendency, but wrinkle his brow at all the unintended consequences. At least, everyone in the region speaks English more or less, otherwise, the European Common Market could learn a lot from studying our local scene. About fifteen years ago, there was actually an unsuccessful provision on the ballot for South Jersey to secede.

Originally published: Monday, June 26, 2006; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 16, 2019