Related Topics

Philadelphia Medicine

The first hospital, the first medical school, the first medical society, and abundant Civil War casualties, all combined to establish the most important medical center in the country. It's still the second largest industry in the city.

Religious Philadelphia

William Penn wanted a colony with religious freedom. A considerable number, if not the majority, of American religious denominations were founded in this city. The main misconception about religious Philadelphia is that it is Quaker-dominated. But the broader misconception is that it is not Quaker-dominated.

Sights to See: The Outer Ring

There are many interesting places to visit in the exurban ring beyond Philadelphia, linked to the city by history rather than commerce.

Science

Science

Tourist Walk in Olde Philadelphia

Colonial Philadelphia can be seen in a hard day's walk, if you stick to the center of town.

Up Market Street to Sixth and Walnut

Millions of eye patients have been asked to read the passage from Franklin's autobiography, "I walked up Market Street, etc." which is commonly printed on eye-test cards. Here's your chance to do it.

Millions of eye patients have been asked to read the passage from Franklin's autobiography, "I walked up Market Street, etc." which is commonly printed on eye-test cards. Here's your chance to do it.

Central Pennsylvania

"Alabama in-between," snickered James Carville, "Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Alabama in-between."

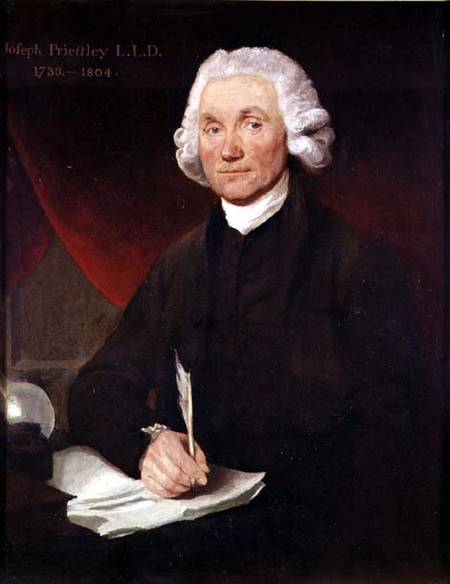

Joseph Priestley, Shaker and Mover

|

| Priestley |

Joseph Priestley, sometimes also spelled Priestly, is surely one of the more undeservedly neglected men of history. He has been called, with justice, the Father of the Science of Chemistry. He might also be called with equal justice, the father of the First Unitarian Church . The First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, at 21st and Walnut, is the first and oldest Unitarian church and was indeed started at the urging of Priestley, whose principal residence was in Northumberland PA, at the confluence of the West and North Branches of the Susquehanna. Priestly wrote a scholarly work on the teachings of Jesus, which so captivated Thomas Jefferson that Jefferson wrote him the outline of another book that needed writing. Apparently, Priestley didn't have time, so in 1803 Jefferson wrote it himself, in the four languages he was fluent in, English, French, Latin, and Greek. Although those were simpler times, there have been few if any others who have told a President of the United States that he was just too busy to respond to a presidential request, particularly when the President could then find he had time to do it himself.

Priestley's theological teachings were based on scientific reasoning. They were highly controversial views, to say the least. He rejected the concept of a Trinity (he was a Calvinist minister, mind you), the divinity of Christ, and the immortality of the soul. Essentially, he rejected the concept of an immortal soul on the reasoning that perceptions and thought were functions of material structures in the human brain (Edmund O. Wilson's idea of Consilience is largely similar), and therefore will not outlive the cerebral tissue which produced them. In 1791, mobs burned his house in Birmingham, England, his patronage was revoked, and he hastily emigrated to Philadelphia. It isn't hard to see why these ideas were particularly unpopular with the Anglican church, which is probably the main reason England made him into a non-person, and his scientific ideas were denigrated as the product of other people.

That's too bad because he really was a scientist of immense importance. As a young man, he encountered Benjamin Franklin in England and was certainly a man after Franklin's heart. He noticed funny things about gases that rose from swamps and over mercury salts, and Franklin encouraged him to systematize and analyze his observations into theory. Although he called it anti-phlogiston, he had discovered oxygen. And then hydrogen, and nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide, and hydrochloric acid. Priestley really was the first organized and coherent scientific chemist, the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, Lavoisier, and Priestley became scientific friends, and enthusiastically exchanged ideas and observations, eventually leading to Lavoisier's fundamental principle: Matter is neither created nor destroyed, it only changes its form. In the end, it made no difference; Priestly had offended some pretty large religions, and nothing he did in chemistry was going to get much attention. Perceiving the value of the land at the confluence of rivers, he made his home for the last ten years of his life in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, now three hours drive Northwest, somehow managing to maintain an active scientific, political and theological influence worldwide. Visiting this rather sumptuous estate in a little river town is well worth a tourist visit. He died in 1804, just after his friend and kindred-religionist Thomas Jefferson became President of the United States.

Priestley's life can be summarized in one of his own most quoted remarks. "In completing one discovery we never fail to get an imperfect knowledge of others of which we could have no idea before so that we cannot solve one doubt without creating several new ones."

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

Originally published: Monday, June 26, 2006; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 22, 2019